CHAPTER III

VILLA GARDENS TO THE WEST OF FUNCHAL

THE miniature gardens described in the previous chapter, which, as a rule, surround the more humble dwellings of the Portuguese, frequently only cover the small piece of ground at the back of the town house, which is either converted into the backyard and rubbish-heap, decorated with old tins and broken china, or converted into a little paradise of flowers, according to the temperament and taste of its owner. Apart from these are the larger gardens surrounding the villas, or quintas, on the outskirts of the town. Most of these gardens are owned by English residents, and to them Madeira owes the introduction of many floral treasures. The first impression of these gardens, taken from a general point of view, is that they are lacking in form, the idea conveyed being that the original owner of the garden made it without any definite plan in view. For that reason they invariably lack any sense of grandeur or repose. It is only fair to say, however, that the landscape gardener has had many difficulties to contend with. The natural slope of the ground is, as a rule, extremely steep, especially in gardens situated on the east side of the town. But the ground by no means necessarily falls away only in front of the house. It as often as not falls to one side as well, which makes terracing a very difficult and serious undertaking. To move earth by means of small baskets carried on men’s backs is a sufficiently serious matter in the East, where coolies are employed at a very low rate of wages, and are accustomed to this method. But in Madeira, where wages are by no means low, this procedure, which is absolutely necessary, has an important financial aspect when laying out a garden. The result is to give the gardens the effect of having been added to bit by bit, and many of them are broken by slanting terraces without any particular meaning. In common with all foreign gardens, they lack the beauty of English turf, as the finer grasses will not withstand the heat and dryness of a Madeira summer. Natal grass, which grows from very small tubers, is the most common substitute for turf, as it is hardy and can be mown fairly close. Some of the finer American grasses have been found successful, especially for growing under large trees, which is most useful, as nothing is so unsatisfactory as the effect of trees growing out of would-be flower-beds. All the beauty of the trees is lost through the outline of the stems being confused by the surrounding plants, which in themselves are probably poor specimens, owing to the fact that they are constantly being starved through the goodness of the soil being absorbed by the roots of the trees.

Stone balustrades are unknown in Madeira, where cement or plaster has to take the place of stone. Simple designs can be carried out by this means, but, as a rule, a low wall, only about two or three feet in height, from which rise at intervals square pillars, originally intended to support the wooden cross-bars of the vine pergola, finishes the terrace and gives it a very characteristic effect. These pillars can be creeper-clad, and either stand alone or support a canopy of wistaria, bignonia, or some other gorgeous creeper.

Any defect in the scheme of the gardens is amply atoned for by the wealth of colour and abundance of flowers they contain, at almost all seasons of the year.

Some of the older gardens were laid out more as pleasure-grounds, and planted with specimen trees brought together from all parts of the New and Old world, and in these especially the lack of good turf is keenly felt. I am thinking of the gardens which surround the Hospicio, which was built in 1856 by the late Empress of Brazil, in memory of her daughter, the Princess Maria Amelia, who died in Madeira.

The garden is well cared for, and contains a good collection of trees and flowering shrubs. Near the entrance are some very fine Ficus comosa and two splendid Jacarandas, which, when they are laden with their blue blossoms, stand out splendidly against the dark evergreen trees; also a very large Coral-tree, whose grey leafless branches are adorned early in the year with scarlet blossoms. In the centre of the garden are two unusually fine specimens of Duranta trees, whose long hanging racemes of orange berries cause them to be much admired all through the winter and spring months, while in summer the branches are laden with their blue blossoms. Dragon-trees, frangipani-trees, judas-trees, camphor-trees, til and Astrapea viscosa, are all to be found here, and a large specimen of the gorgeous flame-coloured Flamboyant or Poinciana, may be easily recognized by its flat spreading branches, which shed their fern-like foliage before the blossoms appear. At all seasons of the year the garden affords a delightful pleasaunce for the inmates of the Hospital, and can never be entirely colourless, as the red dracenas and the bright crimson leaves of the acalypha, which are blotches of a lighter or darker colour, afford a welcome note of colour at all seasons of the year and a relief to the eternal green of the evergreen trees. The walls of the garden are clothed with bougainvilleas, wistarias, and other creepers, and the beds contain a variety of plants, such as clerodendrons, hibiscus, abutilons, begonias, azaleas, and roses. The grass edges to the beds give the garden a character of its own, and might well be copied in other Madeira gardens.

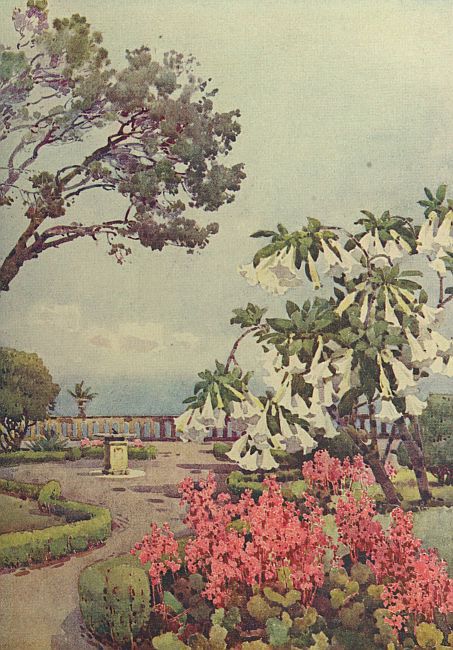

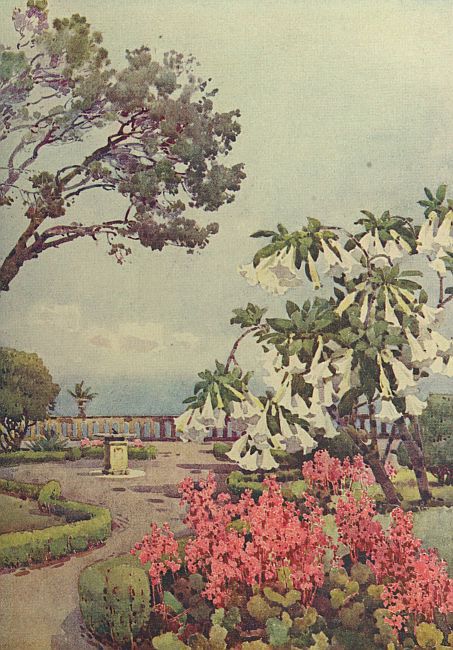

DATURA, QUINTA VIGIA

On the opposite side of the same road at the top of the Augustias Hill stands the Quinta Vigia; the name means a look-out place or watch-post, and no doubt the villa was so called because the grounds command a fine position, the terrace wall ending with a sheer descent 100 feet or more down to the sea. The garden has a fine view of the harbour, the Brazen Head, the distant islands of the Desertas, and the Loo Rock, which lies immediately below the cliff. The late Empress of Austria spent the winter of 1860-61 at this quinta, and since then the property has had various owners. Though the garden is now neglected, as the villa has been uninhabited for some years, the trees remain, and together with those belonging to the adjoining Quinta das Augustias on the one side, and those of the Quinta Pavao on the other, form one of the principal features of the town of Funchal. The day is probably fast approaching when the whole of this property will fall into the hands of an hotel company, but it is to be hoped that some effort will be made to save the trees. From far and near the splendid specimens of Araucaria excelsa form a very important feature in the landscape, as they have attained an immense size. I am told that Mr. William Copeland first introduced these Norfolk Island pines to Madeira, and planted those at Quinta Vigia. They seem to have taken kindly to their adopted country, though not, of course, attaining to the gigantic height of 150 feet, as they are said to do in their native land. The garden also contains a good specimen of Araucaria braziliensis. One of the largest cabbage palms in the island stands near the entrance, and the garden is rich in rare trees. Grevilleas, with deep orange bottle-brush-like flowers; schotia, with its deep crimson-red blossoms; magnolias; the deciduous Taxodium distichum, mango-trees, and hosts of others, adorn the grounds. Among the shrubs are pittosperums, with their leathery grey-green leaves and greenish-white sweet-scented blossoms; also francisceas and great quantities of Euphorbia fulgens, whose long wreaths of orange-scarlet flowers remain in beauty all through January and February. Here are to be seen pittangas, or Eugenia braziliensis, the myrtles of Brazil, with their small shiny foliage and little sweet-smelling white flowers, resembling the common myrtle, only borne on slender stalks; the ribbed orange-coloured fruit is not only very decorative to the shrub, but is valued as a great delicacy among the Portuguese. Murraya exotica has flowers closely resembling orange blossoms in form and fragrance, and appears to flower in spring and autumn. The verandah of the house is clothed in creepers, among which are Allemanda schottii, with its pure yellow blossoms, the deep crimson-flowered Combritum; Thunbergia laurifolia, with its lavender-coloured flowers; and Rhyncospermum jasminoides, whose tiny white starry flowers fill the whole air with their delicious fragrance late in April. Large bushes of the sweet-scented diosma and a small heath are a feature of the garden, while the great number of rose-trees are a legacy of one of its English owners, and in spite of the fact that they are now no longer carefully pruned, they flower in great profusion on immense bushes in December, and again in April.

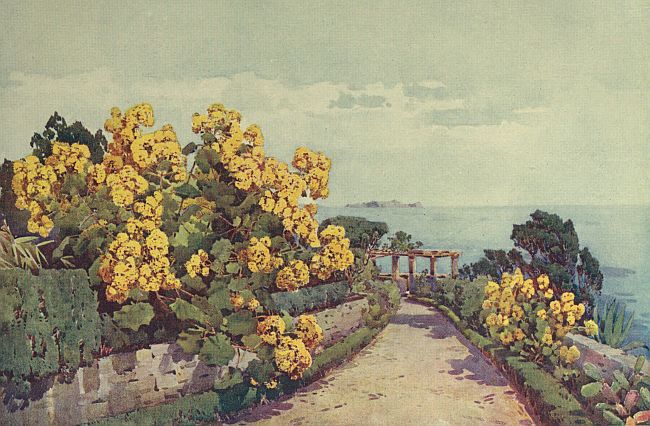

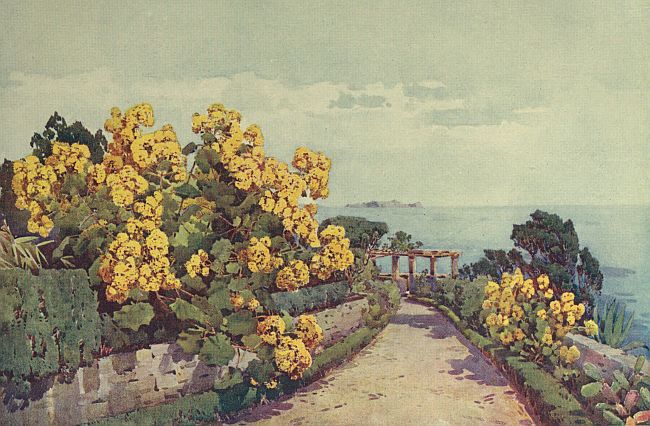

A GROUP OF SENECIO

Near the entrance some large masses of purple and scarlet bougainvillea are to be seen, and by the middle of March the great buds of the immense and rampant-growing solandra are swelling, and in a few days the greenish-white trumpet-shaped flowers will have opened. The beauty of each individual blossom is short-lived: when newly opened it is of a greenish-white, which gradually turns to a deep cream colour, and then, alas! to a most unsightly brown. Unfortunately, the plant shares with thunbergia its ungraceful habit of retaining its blossoms in death, which mars the beauty of the freshly opened flowers. Large clumps of the yellow-flowered Senecio grandifolia are very effective when the great loose heads of blossom are at their best in February. The plant has fine foliage, and though many people despise it and regard it as a weed, on the outskirts of the garden or hanging over a wall it is certainly worthy of a place. Like its humble relation the common groundsel, it has an objectionable habit of scattering its fluffy seed to the four winds of heaven as soon as the plant is out of flower. This, to be sure, could be avoided by cutting off the old flower-heads as soon as they are over, but would be rather a Herculean task in gardens where it has spread into great beds. The plant is impatient of drought, and its foliage soon flags in the heat of the sun unless its roots are well supplied with moisture, and it will be discovered that its roots run far in the ground in search of it, which, combined with its practice of seeding itself in undesirable situations, makes it a dangerous plant to introduce unawares to a garden, as, once established, it is there for good.

Farther to the west of the town are the gardens of Quinta Magnolia, which cover an extensive area, largely increased by the present owner, until they now extend down the slope of the hill to the bed of Ribeiro Secco, or the Dry River. To those interested in the culture of palms these grounds will be of great interest, as the collection is a good one, and includes some very fine specimens, seen to great advantage, standing on slopes of the nearest approach to turf which the island can produce.

WEIGANDIA AND DAISIES

Some of the cabbage and date palms have attained an immense size, and are a great ornament to the landscape, and some fine groups of the curious screw pine, Pandanus odoratissima; it has peculiar flat leaves and an uncouth flower, which bears a strong resemblance to the body of a dead rabbit hanging from the plant! The grounds command fine views, and were laid out for the present owner by an English landscape gardener. There is a curious cave or grotto formed out of the natural rock, clothed with ferns and mosses, which no doubt remains cool and damp through the summer, and forms a welcome retreat from the fierce heat of the sun.

Close by are the grounds of Quinta Stanford, or Quinta Pitta, as it was originally called by its first owner. The gardens have been very much enlarged by their present owner; banana plantations have gradually vanished, and the grounds no longer present the cramped appearance from which they formerly suffered. New-comers to Madeira, as a rule, express great surprise that the gardens are not larger and generally only cover such a very small piece of ground. The value of the land for agricultural purposes—formerly for growing vines, then, possibly, for banana cultivation, and now for sugar-cane—is no doubt largely responsible for this, and also the great difficulty of acquiring a piece of ground of any considerable size in the neighbourhood of Funchal. In many cases even one acre may be owned by several different landlords, land being divided into incredibly small holdings.

CYPRESS AVENUE, QUINTA STANFORD

In this respect the owners of Quinta Stanford are to be envied, as the house stands well surrounded by its own ground, out of sight of the too common unsightly fazenda and its inevitable squalid cottages. From the terrace in front of the house the view is unrivalled, comprising a fine view of the sea and an unbroken view of the mountains behind the town of Funchal. It is easily seen that the garden is tended with unceasing care by its present owner, and near the entrance some judicious massing of shrubs and flowering trees has in a very few years well repaid the planter; some large clumps of weigandias, Astrapea pendiflora, and bushes of common white marguerite daisies of mammoth proportions give a broader effect than is usual in most Madeira gardens. To my mind, the very greatest praise should also be given to the owner for having planted an avenue of cypresses, almost the noblest and grandest of all trees, especially when seen under a southern sun, and their absence in the landscape of Madeira is keenly felt. The Portuguese see no beauty in them, and only connect them with death, for which reason they are scarcely ever seen except in cemeteries. From the astonishing growth which the young trees at Quinta Stanford have made in a few years, it is evident that the soil is very favourable for their culture, and it seems almost incredible that more owners of gardens, who must have seen what Italy owes to her cypresses, should not have planted them in Madeira; but it is to be hoped that even now others may follow the excellent example set before them at Quinta Stanford.

The owner of the garden has much to tell of the successes and failures he has made, not only with imported plants, in the hopes of inducing them to find a new home in Madeira, but he journeyed far and wide to make a collection of the native ferns, of which there are a great quantity. Many of them, removed from the cool, damp air of their mountain homes, pined and died a lingering death in the air of Funchal, which was too hot and dry; and the atmosphere of a stufa, or greenhouse, is unsuited to the hardier ferns.

Some interesting experiments have also been made with rock-plants, in order to see whether it would be possible to induce any of our favourite Alpine plants to adopt a home in warmer climes; but I fear, though some may survive for a year or two, in the end they will grow steadily smaller, until they dwindle away and cease to exist. So I am afraid the making of a rock-garden in the sense which we in England regard a rock-garden—i.e., an artificial arrangement of rocks, clothed with carpets and cushions of flowering Alpine plants—will never be possible in Madeira. Here the rock-garden must remain as Nature intended it to be—rocks and cliffs, interspersed with prickly-pear, agaves, cactus, some of the larger saxifrages, and such native plants as Echium fastuosum.

The gardens owned by the English suffer, as a rule, somewhat severely from the absence of their owners just at the season of the year when they require the closest care and attention, and this may possibly account for the failure to acclimatize many of these imported treasures. If they could be tended with loving hands, screened from the fiercest of the sun’s rays, given exactly the amount of water they require, no doubt there would be many less failures; but the ignorant Portuguese gardener probably either starves the plant by entirely omitting to water it, especially if it is unlucky enough to be out of reach of the hose, or else he drowns it with too much water, until the ground surrounding it becomes a swamp: for the conditions suitable to a rock-plant would be as unknown to him as the conditions required by a bog-plant.

Some tree-ferns in a sheltered corner make a very good effect, and seem likely, from the strong growth they have made in a few years, to become very fine specimens.

On the terrace near the house are beds of begonias, roses, geraniums, heliotropes, sweet olives, and the garden flowers common to most Madeira gardens, while the walls are clad with a succession of creepers; so all through the winter months the garden remains a feast of colour.

Eighteen years ago the ground which is now the beautiful garden of the Palace Hotel was nothing but rocky, waste ground, bare of vegetation, except for the clumps of prickly-pear, agaves, and cacti which take possession of all the rocky ground along the shore. For situation the garden is unrivalled, and though the garden lacks the care and attention which naturally are bestowed on a private garden, the luxuriant growth, especially of the creepers, has converted the formerly waste ground into a beautiful jungle of flowers. The garden is devoid of any fine trees, except for the ficus trees, a few oaks, and a stray cypress or two which surround the Dépendence, which was formerly a private house; it stands at the very edge of the precipitous cliff, where the unceasing roar of the surf rings in one’s ears as it dashes almost against its very walls. In front of the main building are some large cabbage palms, affording welcome shade and shelter, which have made astonishingly rapid growth, as only ten years ago they were merely items in flower-beds, and I little thought that on my second visit to the island, some seven years later, they would have become an important feature in the garden.

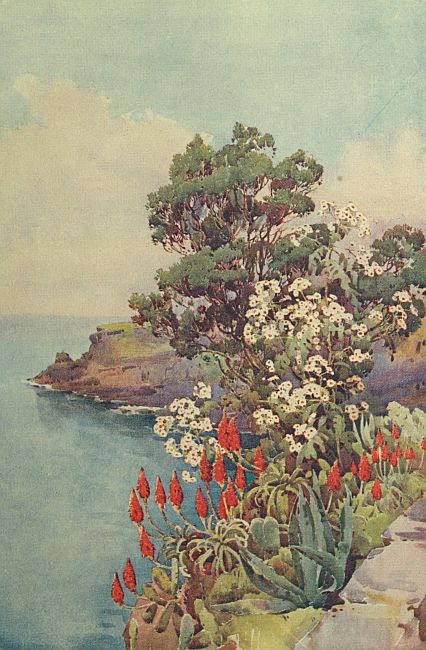

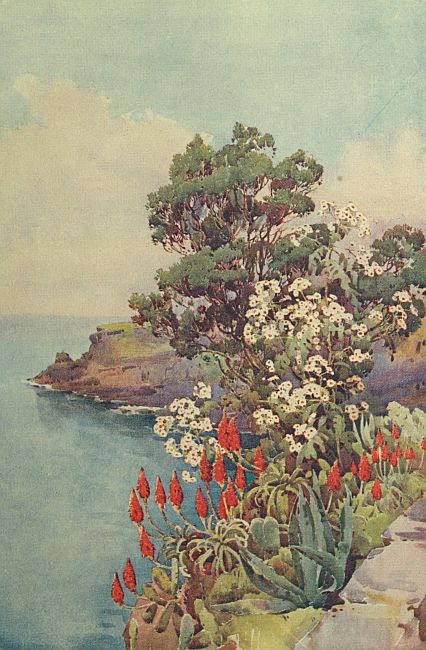

ALOES AND DAISY TREE

Early in December, when the whole island is fresh and green after the autumn rains, and presents more the aspect of spring than late autumn or even winter, the view from the garden is surprisingly beautiful. The cliffs have broad stretches of the brilliant red-flowered Aloe arborescens, with its large rosettes of glaucous grey-green leaves, which makes the plant always ornamental, even when it is not adorned with its hundreds of scarlet flower spikes. Some people say it was always indigenous to the island, and found its home in the Santa Luzia ravine. Whether this is really the case I feel doubtful, as Mr. Lowe, in his “Flora of Madeira,” quotes it as one of the plants which has become naturalized, though probably originally introduced. Growing on the cliffs the flowers show to great advantage, standing out in sharp contrast to the deep blue sea below, but it is a great ornament wherever it grows, whether in clusters overhanging a wall where its rosettes of leaves overlap each other in thick tufts in endless succession till there seems no reason why they should ever stop, or clothing the rocky ground on the hillside among the pine-trees.

At the same season the Franzeria artemesioides, or daisy-trees, as they are commonly called, are in full beauty. The best method of treating these trees is to cut them back when they have done flowering, as the large clusters of daisy-like flowers appear on the long shoots of young wood. When their flowering season is over, they lose their large grey-green leaves, so it is lucky that the tree can be so treated, or the long bare branches would make them unsightly at other seasons. The hedges and bushes of Plumbago capensis attain to mammoth proportions when they can escape the attention of the gardener’s ruthless shears, and are laden with their lovely soft blue blossoms in late November and December. Then comes a season of rest, though the plant is seldom entirely devoid of colour, and in early spring fresh shoots give promise of a wealth of blossom again in April and May.

Bougainvilleas have been planted with a lavish hand, but unluckily with no regard for colour. I sometimes wondered if the Portuguese gardeners are all colour-blind, as it is by no means uncommon to see a bright purple bougainvillea planted side by side with a scarlet one, and as likely as not, interlaced with a flaming orange bignonia, while the bright pink Charles Turner geranium grows happily below. In Madeira gardens colour runs riot, and I own that the prolonged flowering season of many of the creepers and shrubs makes the colour scheme more difficult than it is in our English gardens.

The great clumps of Crinum powellei are a remarkable feature of this garden, when late in April the great bulbs send up their spikes of either pure white flowers or white delicately flushed with pink. The flowers come in six to ten in an umbel, on stems three to five feet in height, and are very freely produced—large clumps sending up a dozen or more flower-heads at the same time. The bulb has long narrow green foliage, which is very ornamental. The flowers have a delicate but somewhat sickly scent; the plant is a native of Natal, and, like others of its compatriots, has taken kindly to the climate and soil of Madeira.

It would be impossible to enumerate all the host of other plants the garden contains—creepers, shrubs, flowering trees, besides roses, begonias, geraniums, heliotropes, in an almost endless list—while the cliffs have remained a natural rock-garden. In the clefts of the rocks giant agaves occasionally throw up their great flower-heads fifteen feet or more in height, and then the plant, as if exhausted by the supreme effort in the climax of its existence, dies; but it is quickly replaced by hundreds of others, as the seed of the monster flower has found fresh ground in every nook and cranny. Besides the agaves, clumps of prickly-pear, or Opuntia tuna, with its curious succulent growth clothed with poisonous thorns, some wild saxifrages and tufts of Echium fastuosum, known as Pride of Madeira, have all found a home.

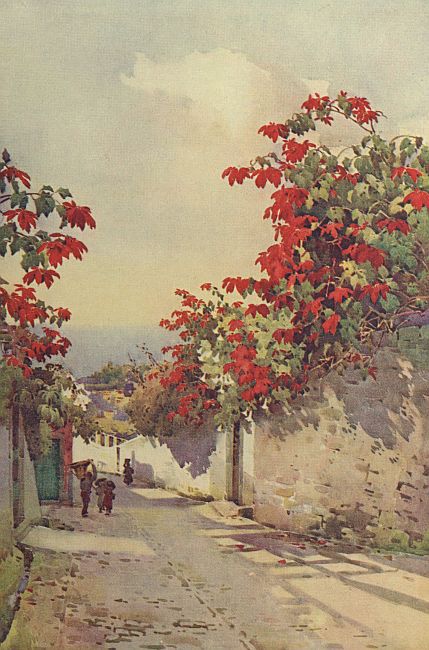

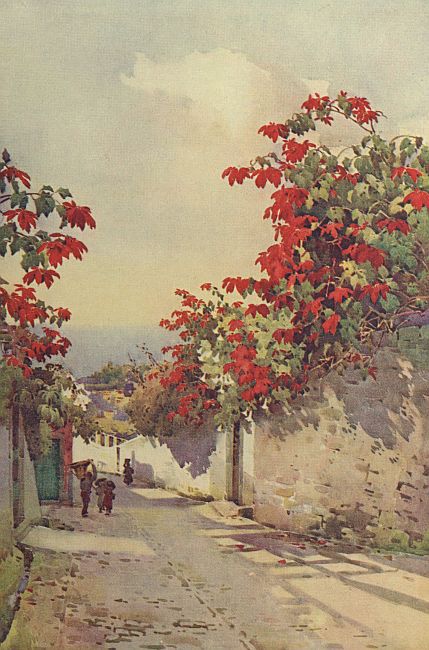

This garden is the last one of any interest on the west side of the town, as beyond lie only a few modern villas in the worst possible taste, with no grounds worthy of the name of a garden; but almost opposite to the hotel in the grounds of Casa Branca for a few short weeks in the year the avenue of Poinsettia pulcherrima interspersed with date palms and clumps of strelitzias is worth seeing. The poinsettia blooms are almost the largest I have ever seen, measuring quite eighteen inches in diameter from point to point of the scarlet leaves. Like the daisy tree, the poinsettia flowers on the young wood, and throws out fresh branches six to ten feet long, which can be cut back in January, when the beauty of the blossoms is gone and the foliage becomes an unsightly yellow and at length drops altogether. When seen growing in all their luxuriant and garish splendour, it is difficult to remember that it is the same plant that one has seen in a weakly and attenuated form in our English stove-houses, with one poor little flower-head at the end of a single stem imperfectly clad with sickly foliage. Poinsettias seem to rejoice in rich soil, and they appear to revel in the liberal feeding of the adjoining banana plantations, which, no doubt, they deprive of a good deal of nourishment; but they well repay their owner, as in the glow of the western sun they provide a veritable feast of colour all through December.

POINSETTIA ON THE MOUNT ROAD