C-3. EMPLOYMENT DURING DEFENSIVE OPERATIONS

A sniper team may effectively enhance or augment any company’s defensive fire plan.

After analyzing the terrain, the sniper team should recommend options to the company commander.

a. Defensive Operations. During defensive operations, a sniper team may perform the following:

• Overwatch obstacles and demolitions.

• Perform counterreconnaissance (destroy enemy reconnaissance elements).

• Engage enemy observation posts, armored-vehicle commanders exposed in turrets, and ATGM teams.

• Damage enemy vehicle optics to degrade movement.

• Suppress enemy crew-served weapons.

• Disrupt enemy follow-on units with long-range rifle fire.

b. Primary Positions. Sniper teams are generally positioned to observe or control one or more avenues of approach into the defensive position. The types of weapons systems available to the sniper team may lead the company commander to use his sniper team against secondary avenues of approach to increase all-round security and to allow him to concentrate his combat power against the most likely enemy avenue of approach.

Sniper teams may support the company by providing precise extra optics for target acquisition and long-range rifle fires to complement those of the M249 machine gun.

This arrangement best utilizes the company’s weapons systems. Sniper teams may also be used in an economy-of-force role to cover dismounted enemy avenues of approach that the company cannot cover with other available assets.

c. Alternate and Supplementary Positions. A sniper team establishes alternate and supplementary positions for all-round security. Positions near the FEBA are vulnerable to concentrated enemy attacks, enemy artillery, and obscurants. The sniper team and designated marksmen can be positioned for surveillance and mutual fire support. If possible, they should establish positions in depth for continuous support during the fight.

The sniper's rate of fire neither increases nor decreases as the enemy approaches. Specific targets are systematically and deliberately shot; accuracy is far more important than speed.

d. Overwatch. The sniper team can be placed to overwatch key obstacles or terrain such as river-crossing sites, bridges, and minefields that canalize the enemy directly into engagement areas. Sniper weapons are mainly used where other weapons systems are less C-4

FM 3-21.11

effective due to security requirements or terrain. Even though the company commander has access to weapons systems with greater ranges and optical capabilities than those of the sniper weapons, he may be unable to use these for any of several reasons. Unlike sniper weapons, the other weapons systems may present too large a firing signature, be difficult to conceal, create too much noise, or be needed more in other areas. The sniper team can provide the company commander with greater observation capability and killing range than other subordinate units.

e. Counterreconnaissance. The sniper team can be used as an integral part of the counterreconnaissance effort. The team can help acquire and destroy targets. It can augment the counterreconnaissance element by occupying concealed positions for long periods. It also can observe direct and indirect fires (to maintain their security) and engage targets. Selective long-range rifle fires are difficult for the enemy to detect. A few well-placed shots can disrupt enemy reconnaissance efforts, force him to deploy into combat formations, and deceive him as to the location of the main battle area. The sniper team’s stealth skills counter the skills of enemy reconnaissance elements. The sniper team can be used where infantry platoon mobility is unnecessary, freeing squad designated marksmen to cover other sectors. The sniper team also can be used to direct ground maneuver elements toward detected targets. This helps to maintain their security so they can be used against successive echelons of attacking enemy.

f. Strongpoint. The commander employs the sniper team to support any unit defending a strongpoint. The sniper team's characteristics enable it to independently harass and observe the enemy in support of the force in the strongpoint, either from inside or outside the strongpoint.

g. Reverse-Slope Defense. The sniper team can provide effective long-range rifle fires from positions forward of the topographical crest or on the counterslope if the company is occupying a reverse-slope defense.

C-4. EMPLOYMENT

DURING

STABILITY OPERATIONS

During stability operations, US troops are usually required to use a minimal amount of force to respond to threats. Even with well-understood ROE, it may be difficult for an SBCT infantry company to respond with minimum force rather than maximum force when confronted with certain situations. The sniper team is an important tool for the company commander during stability operations.

a. During stability operations, a sniper team may perform the following:

• Conduct active or passive countersniper missions.

• Overwatch a checkpoint.

• Monitor a public gathering.

• Identify critical people in a crowd.

• Reinforce a base camp's security.

• Conduct any offensive or defensive sniper mission.

b. The sniper team provides the company commander the required minimum force (or an equal or reasonable response to force used against the company) through its precision long-range rifle fires.

c. Sniper teams also provide the company commander with a ready source of information to counter a perceived sniper threat. Through the team’s understanding of sniping and sniper hiding places, it can provide the commander with invaluable

C-5

FM 3-21.11

information. The company commander incorporates this information into his METT-TC

analysis to develop a countersniper plan.

C-5. ACTIONS IN A BUILT-UP AREA

The unlimited use of firepower during urban operations may undermine the commander’s intent. The sniper team is an incredible asset to the SBCT infantry company commander while operating in a built-up area.

a. Offensive Operations. Assaulting forces usually encounter fortified positions prepared by the defending force. These can range from field-expedient, hasty positions produced with locally available materials to elaborate steel and concrete emplacements complete with turrets, underground tunnels, and crew quarters. Field-expedient positions are those most often encountered. However, the company commander should expect elaborate positions when the enemy has significant time to prepare his defense. The enemy may have fortified weapons emplacements or bunkers, protected shelters, reinforced natural or constructed caves, entrenchments, and other obstacles.

(1) The enemy will try to locate these positions so they are mutually supporting and arrayed in depth across the width of his sector. The enemy also will try to increase his advantages by covering and concealing positions and by preparing direct fire plans and counterattack contingencies. Because of this, fortified areas should be bypassed and contained by a smaller force.

(2) Sniper precision fire and observation capabilities are invaluable in the assault of a built-up area. Precision rifle fire can readily detect and destroy pinpoint targets invisible to the naked eye. The sniper team’s role during the assault of a fortified position is to deliver precision long-range rifle fire against the embrasures, air vents, and doorways of key enemy positions; against observation posts; and against exposed personnel. The company commander must plan the sequence in which the sniper team will destroy targets. This should systematically reduce the enemy's defenses by denying the ability of enemy positions to support each other. Once these positions are isolated, they can be more easily reduced. Therefore, the company commander must decide where he will try to penetrate the enemy's fortified positions and then employ his sniper team against those locations. The sniper team can provide continuous fire support for both assaulting and other nearby units when operating from positions near the breach point on the flanks. Its precision rifle fires add to the effectiveness of the entire company. Frequently, when various factors prevent the use of other precision weapons, such as Javelins, snipers are still useful.

(3) The sniper team plans based on information available. The enemy information needed by a sniper team includes the following:

• Extent of and exact locations of individual and underground fortifications.

• Fields of fire, directions of fire, number and locations of embrasures, and types of weapons systems in the fortifications.

• Locations of entrances, exits, and air vents in each emplacement and building.

• Locations and types of existing and reinforcing obstacles.

• Locations of weak spots in the enemy's defense.

b. Defensive Operations. The sniper precision-fire and observation capabilities are equally invaluable in the defense of a built-up area. As in the offense, the sniper team detects and destroys targets that are invisible to the naked eye. The company commander C-6

FM 3-21.11

generally positions the sniper team to observe or control one or more avenues of approach into the built-up area. This focus generally is on secondary avenues of approach. This employment option allows the commander to concentrate the majority of his combat power against the enemy’s most likely avenue of approach while still having a formidable force on the secondary avenue of approach. The company commander can also position the sniper team and the squad designated marksmen to support or complement each other. Finally, the company commander can employ the sniper team to independently harass and observe the enemy in support of the company’s mission.

C-7

FM

3-21.11

APPENDIX D

TLP-MDMP INTEGRATION

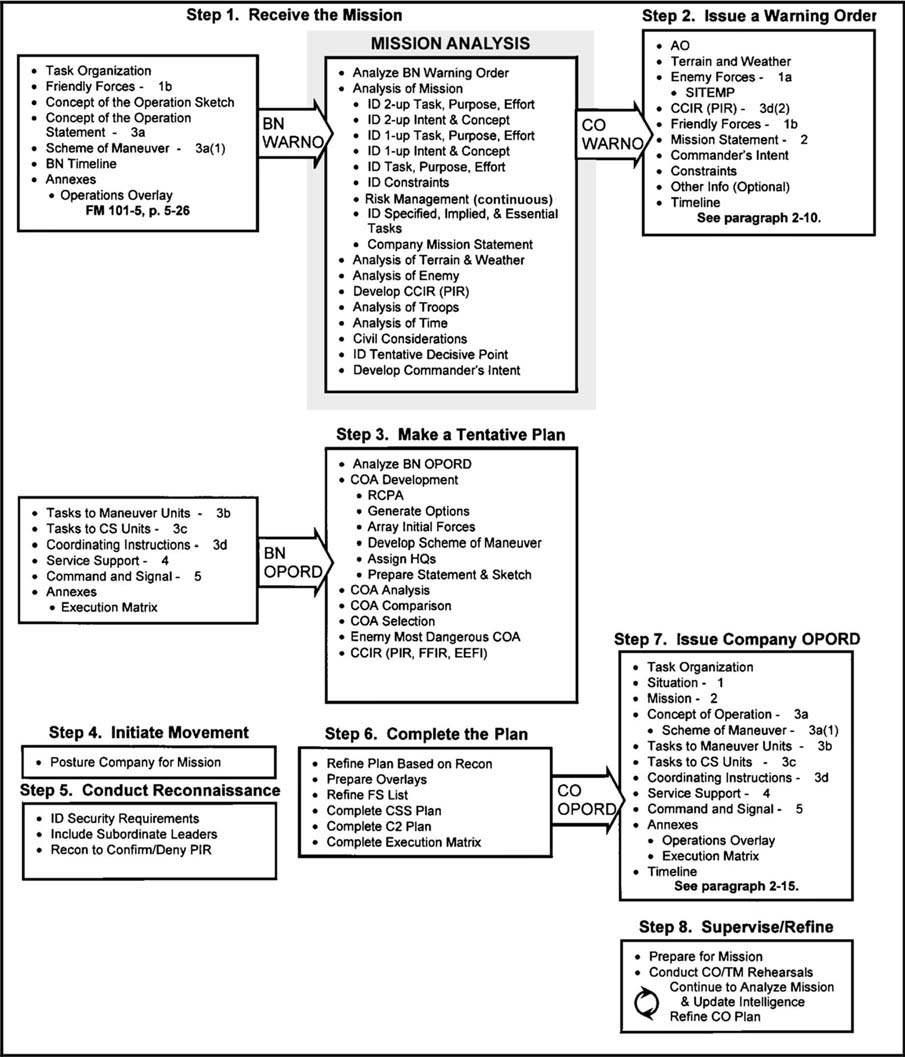

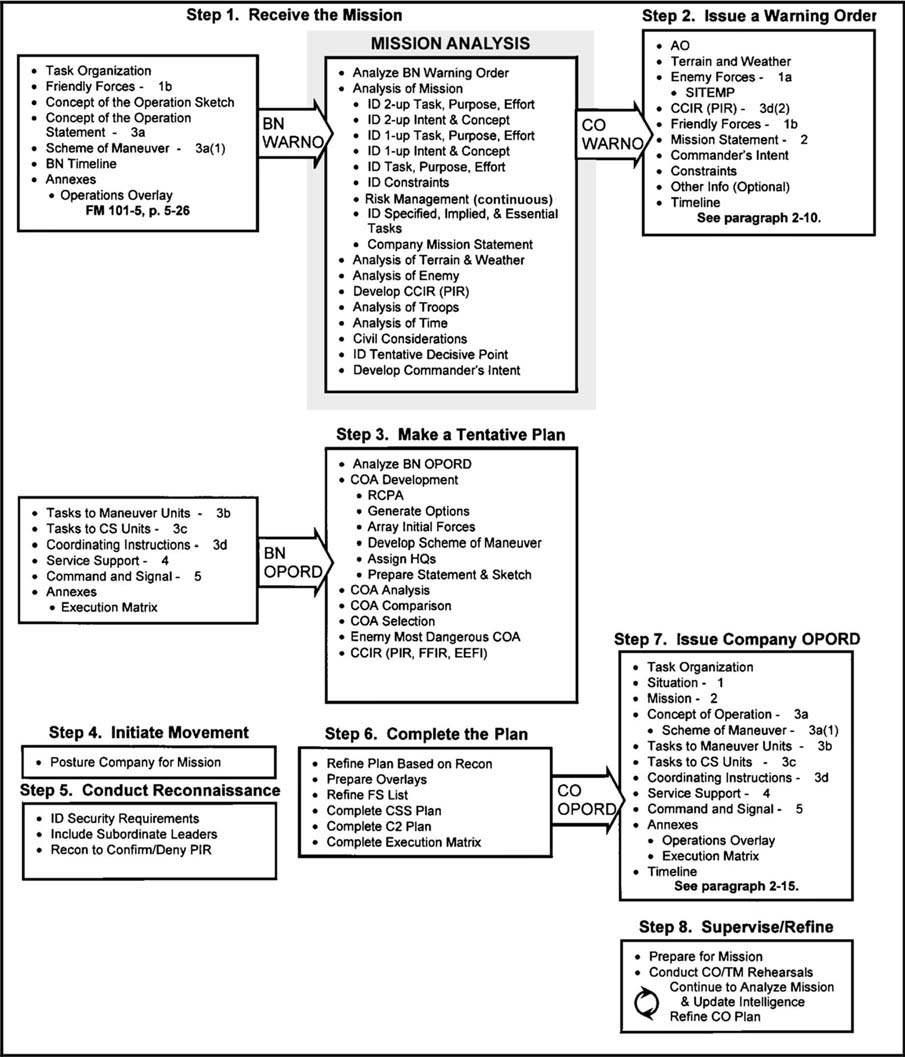

The troop-leading procedures are integrally coupled and consistent with the military decision-making process described in FM 101-5. The two processes are not identical, however, because the specific steps of the MDMP are designed to help commanders and their staffs develop a plan.

While company commanders have subordinate leaders who assist with aspects of planning operations, these leaders are not company staff officers. The TLP reflect this reality while incorporating the general process of the MDMP.

D-1. LINKING THE TLP AND MDMP.

The troop-leading procedures are a sequence of actions that enable the company commander to use available time effectively in the preparation and execution of company missions. They are tools to assist the company commander in making decisions, issuing combat orders, and supervising operations. The MDMP and TLP are linked by information sharing and flow. The type, amount, and timeliness of the information from battalion to company directly impact the company commander’s TLP. FM 101-5

describes a process in which the company commander receives three battalion warning orders prior to the battalion OPORD being issued. This is situationally dependent. All staffs in all situations may not follow the MDMP steps as listed in FM 101-5 for a variety of reasons (such as time, experience level, tactical situation, and so on). However, as a

guide, the company TLP must be inextricably linked to the information flow from the next higher headquarters.

D-2. PARALLEL AND COLLABORATIVE PLANNING

Parallelism and collaboration are inherent planning concepts in both the MDMP and TLP.

They ultimately provide the important linkage between the planning processes. Concurrent effort and sharing of information are critical to the company commander’s efficient, effective planning and the company’s successful mission accomplishment. Figure D-1, page D-2, depicts the importance of parallelism and collaboration between the MDMP (battalion) and the TLP (company), with references to specific paragraphs in the OPORD.

DRAFT D-1

FM 3-21.11

Figure D-1. TLP inputs.

D-2 DRAFT

FM 3-21.11

APPENDIX E

RISK MANAGEMENT

Risk is the chance of injury or death for individuals and damage to or loss of vehicles and equipment. Risk, or the potential for risk, is always present in every combat and training situation the SBCT company commander faces. Risk management must take place at all levels of the chain of command during each phase of every operation; it is an integral part of all tactical planning. The company commander, platoon leaders, NCOs, and all other soldiers must know how to use risk management, coupled with fratricide avoidance measures, to ensure that the mission is executed in the safest possible environment within mission constraints.

The primary objective of risk management is to help units protect their combat power through accident prevention, enabling them to win the battle quickly and decisively with minimal losses. This appendix outlines the process leaders use to identify hazards and implement a plan to address each identified hazard. It also discusses the responsibilities of the company’s leaders and individual soldiers in implementing a sound risk management program. For additional information on risk management, refer to FM 100-14.

Section I. RISK MANAGEMENT PROCEDURES

This section outlines the five steps of risk management. A company commander should never approach risk management with “one size fits all” solutions to the hazards the company will face. Rather, in performing the steps, he must keep in mind the essential tactical and operational factors that make each situation unique.

E-1. STEP 1, IDENTIFY HAZARDS

A hazard is a source of danger. It is any existing or potential condition that could entail injury, illness, or death of personnel; damage to or loss of equipment and property; or some other sort of mission degradation. Tactical and training operations pose many types of hazards. The company leadership must identify the hazards associated with all aspects and phases of the company mission, paying particular attention to the factors of METT-TC. Risk management must never be an afterthought; leaders must begin the process during their troop-leading procedures and continue it throughout the operation. Table E-1, page E-2, lists possible sources of battlefield hazards that the unit might face during a typical tactical operation. The list is organized according to the factors of METT-TC.

E-1

FM 3-21.71

MISSION

• Duration of the operation.

• Complexity/clarity of the plan. (Is the plan well-developed and

easily understood?)

• Proximity and number of maneuvering units.

ENEMY

• Knowledge of the enemy situation.

• Enemy capabilities.

• Availability of time and resources to conduct reconnaissance.

TERRAIN AND WEATHER

• Visibility conditions, including light, dust, fog, and smoke.

• Precipitation and its effect on mobility.

• Extreme heat or cold.

• Additional natural hazards (broken ground, steep inclines, water obstacles).

TROOPS

• Equipment status.

• Experience the units conducting the operation have working

together.

• Danger areas associated with the unit’s weapon systems.

• Soldier/leader proficiency.

• Soldier/leader rest situation.

• Degree of acclimatization to environment.

• Impact of new leaders or crewmembers.

• Friendly unit situation.

• NATO or multinational military actions combined with U.S. forces.

TIME AVAILABLE

• Time available for troop-leading procedures and rehearsals by

subordinates.

• Time available for PCCs/PCIs.

CIVIL CONSIDERATIONS

• Applicable ROE or ROI.

• Potential stability and support operations involving contact with civilians (such as NEOs, refugee or disaster assistance, or

counterterrorism).

• Potential for media contact and inquiries.

• Interaction with host nation or other participating nation support.

Table E-1. Examples of potential hazards.

E-2. STEP 2, ASSESS HAZARDS TO DETERMINE RISKS

Hazard assessment is the process of determining the direct impact of each hazard on an operation (in the form of hazardous incidents). Use the following steps.

a. Determine hazards that can be eliminated or avoided.

b. Assess each hazard that cannot be eliminated or avoided to determine the probability that the hazard can occur.

c. Assess the severity of hazards that cannot be eliminated or avoided. Severity, defined as the result or outcome of a hazardous incident, is expressed by the degree of injury or illness (including death), loss of or damage to equipment or property, environmental damage, or other mission-impairing factors (such as unfavorable publicity or loss of combat power).

E-2

FM

3-21.71

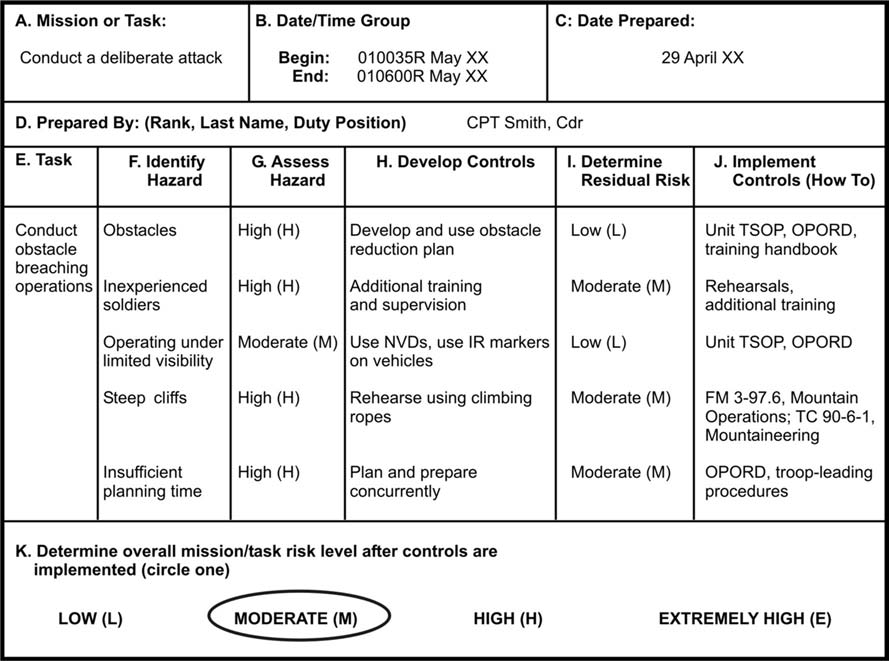

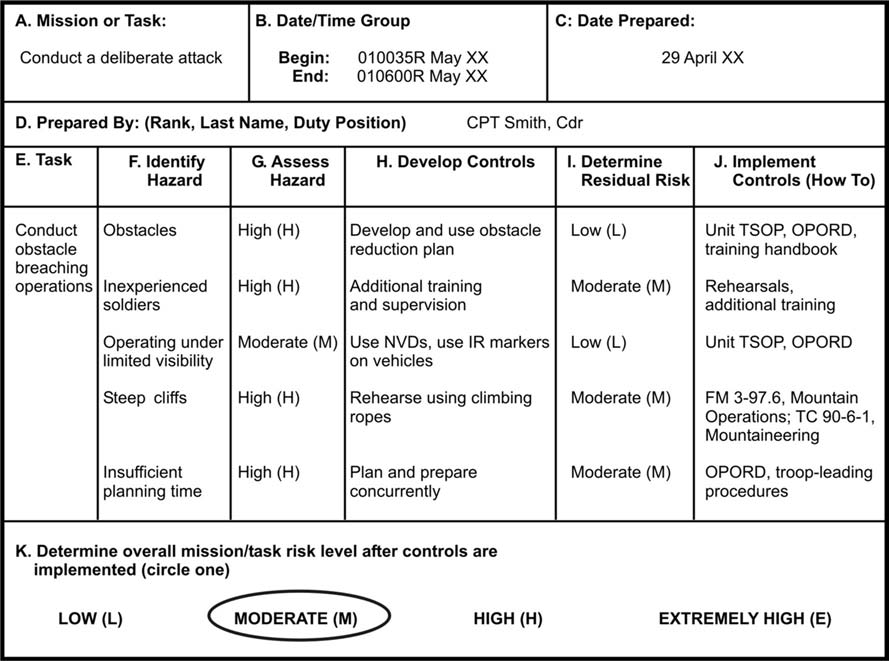

d. Taking into account both the probability and severity of a hazard, determine the associated risk level (extremely high, high, moderate, and low). Table E-2 summarizes the four risk levels.

e. Based on the factors of hazard assessment (probability, severity, and risk level, as well as the operational factors unique to the situation), complete the risk management worksheet. Figure E-1 shows a completed risk management worksheet.

RISK LEVEL

MISSION EFFECTS

Extremely High (E)

Mission failure if hazardous incidents occur in

execution.

High (H)

Significantly degraded mission capabilities in

terms of required mission standards. Not

accomplishing all parts of the mission or not

completing the mission to standard (if hazards

occur during mission).

Moderate (M)

Expected degraded mission capabilities in terms

of required mission standards. Reduced mission

capability (if hazards occur during the mission).

Low (L)

Expected losses have little or no impact on

mission success.

Table E-2. Risk levels and impact on mission execution.

Figure E-1. Completed risk management worksheet.

E-3

FM 3-21.71

E-3. STEP 3, DEVELOP CONTROLS AND MAKE RISK DECISIONS

This step is accomplished in two substeps: develop controls and make risk decisions.

These substeps are accomplished during the “make a tentative plan” step of the troop-leading procedures.

a.

Developing Controls. After assessing each hazard, develop one or more controls that will either eliminate the hazard or reduce the risk (probability, severity, or both) of potential hazardous incidents. When developing controls, consider the reason for the hazard, not just the hazard by itself.

b.

Making Risk Decisions. A key element in the process of making a risk decision is determining whether accepting the risk is justified or, conversely, is unnecessary. The decision-maker must compare and balance the risk against mission expectations. He alone decides if the controls are sufficient and acceptable and whether to accept the resulting residual risk. If he determines the risk is unnecessary, he directs the development of additional controls or alternative controls; as another option, he can modify, change, or reject the selected COA for the operation.

E-4. STEP 4, IMPLEMENT CONTROLS

Controls are the procedures and considerations the unit uses to eliminate hazards or reduce their risk. Implementing controls is the most important part of the risk management process; this is the chain of command’s contribution to the safety of the unit. Implementing controls includes coordination and communication with appropriate superior, adjacent, and subordinate units and with individuals executing the mission. The company commander must ensure that specific controls are integrated into operations plans (OPLANs), OPORDs, SOPs, and rehearsals. The critical check for this step is to ensure that controls are converted into clear, simple execution orders understood by all levels. If the leaders have conducted a thoughtful risk assessment, the controls will be easy to implement, enforce, and follow. Examples of risk management controls include the following:

• Thoroughly brief all aspects of the mission, including related hazards and controls.

• Conduct thorough PCCs and PCIs.

• Allow adequate time for rehearsals at all levels.

• Drink plenty of water, eat well, and get as much sleep as possible (at least 4

hours in any 24-hour period).

• Use buddy teams.

• Enforce speed limits, use of seat belts, and driver safety.

• Establish recognizable visual signals and markers to distinguish maneuvering units.

• Enforce the use of ground guides in assembly areas and on dangerous terrain.

• Establish marked and protected sleeping areas in assembly areas.

• Limit single-vehicle movement.

• Establish SOPs for the integration of new personnel.

E-4

FM

3-21.71

E-5. STEP 5, SUPERVISE AND EVALUATE

During mission execution, leaders must ensure that risk management controls are properly understood and executed. Leaders must continuously evaluate the unit’s effectiveness in managing risks to gain insight into areas that need improvement.

a.

Supervision. Leadership and unit discipline are the keys to ensuring that effective risk management controls are implemented.

(1) All leaders are responsible for supervising mission rehearsals and execution to ensure standards and controls are enforced. In particular, NCOs must enforce established safety policies as well as controls developed for a specific operation or task. Techniques include spot checks, inspections, situation reports (SITREPs), confirmation briefs, buddy checks, and close supervision.

(2) During mission execution, leaders must continuously monitor risk management controls, both to determine whether they are effective and to modify them as necessary.

Leaders must also anticipate, identify, and assess new hazards. They ensure that imminent danger issues are addressed on the spot and that ongoing planning and execution reflect changes in hazard conditions.

b.

Evaluation. Whenever possible, the risk management process should also include an after-action review (AAR) to assess unit performance in identifying risks and preventing hazardous situations. During an AAR, leaders should assess whether the implemented controls were effective. Following the AAR, leaders should incorporate lessons learned from the process into unit SOPs and plans for future missions.

Section II. IMPLEMENTATION RESPONSIBILITIES

Leaders and individuals at all levels are responsible and accountable for managing risk.

They must ensure that hazards and associated risks are identified and controlled during planning, preparation, and execution of operations. The company leadership and their senior NCOs must look at both tactical risks and accident risks. The same risk management process is used to manage both types of risk. The commander alone determines how and where he is willing to take tactical risks. The commander manages accident risks with the assistance of his officers, NCOs, and individual soldiers.

E-6. BREAKDOWN OF THE RISK MANAGEMENT PROCESS

Despite the need to advise higher headquarters of a risk taken or about to be assumed, the risk management process may break down. Such a failure can be the result of several factors; most often, it can be attributed to one or more of the following:

• The risk denial syndrome in which leaders do not want to know about the risk.

• A soldier who believes that the risk decision is part of his job and does not want to bother his unit leadership.

• Outright failure to recognize a hazard or the level of risk involved.

• Overconfidence on the part of an individual or the unit in being able to avoid or recover from a hazardous incident.

• Subordinates who do not fully understand the higher commander’s guidance regarding risk decisions.

E-5

FM 3-21.71

E-7. RISK MANAGEMENT COMMAND CLIMATE

The company commander gives the company direction, sets priorities, and establish