While the above historical example illustrates a critical aspect of stability and civil support operations, it subtly reveals another important lesson for Army commanders.

Many of our future coalition partners and assisting governmental and

nongovernmental organizations will bring key insights to UO (particularly dealing with 9-8

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Stability and Civil Support Operations

urban societies) based on their historical and operational experience. Army

commanders and their staffs should seek out and remain open to others’ unique

understandings that are based on hard-earned and well-analyzed lessons learned.

Participating Organizations and Agencies

9-22. Across the spectrum of urban operations, but more so in these operations, numerous NGOs may be involved in relieving adverse humanitarian conditions. Dense populations and infrastructure make an urban area a likely headquarters location for them. (In 1994 during OPERATION UPHOLD DEMOCRACY, for example, over 400 civilian agencies and relief organizations were operating in Haiti.) Therefore, commanders should assess all significant NGOs and governmental agencies operating (or likely to operate) in or near the urban area to include their—

z

Functions, purposes, or agendas.

z

Known headquarters and operating locations.

z

Leadership or senior points of contact (including telephone numbers).

z

Communications capabilities.

z

Potential as a source for critical information.

z

Financial abilities and constraints.

z

Logistic resources: transportation, energy and fuel, food and water, clothing and shelter, and emergency medical and health care services.

z

Law enforcement, fire fighting, and search and rescue capabilities.

z

Refugee services.

z

Engineering and construction capabilities.

z

Other unique capabilities or expertise.

z

Previous military, multinational, and interagency coordination experience and training.

z

Rapport with the urban population.

z

Relationship with the media.

z

Biases or prejudices (especially towards participating U.S. or coalition forces, other civilian organizations, or elements of the urban society).

Commanders can then seek to determine the resources and capabilities that these organizations may bring and the possible problem areas to include resources or assistance they will likely need or request from Army forces. These organizations will be critical to meeting the population’s immediate needs and minimizing the effects of collateral damage or disaster. However, commanders should consider whether a close relationship with any of these organizations will compromise the organization’s appearance of neutrality (particularly threat perceptions) and adversely affect their ability to assist the population.

SHAPE

9-23. Commanders conduct many activities to shape the conditions for successful decisive operations. In urban stability and civil support operations, two activities rise to the forefront of importance: aggressive IO

and security operations.

Vigorous Information Operations

9-24. IO, particularly psychological operations (PSYOP) and the related activities of civil affairs (CA) and public affairs, are essential to shape the urban environment for the successful conduct of stability or civil support operations. Vigorous IO can influence the perceptions, decisions, and will of the threat, the urban population, and other groups in support of the commander’s mission. IO objectives are translated to IO

tasks that are then executed to create the commander’s desired effects in shaping the battlefield. These operations can isolate an urban threat from his sources of support; neutralize hostile urban populations or gain the support of neutral populations; and mitigate the effects of threat IO, misinformation, rumors, confusion, and apprehension. Developing effective measures of effectiveness is essential to a good IO

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

9-9

Chapter 9

campaign strategy. One of the most valuable methods for obtaining data for use in this process is face-toface encounters with targeted audiences by unit patrols and HUMINT, PSYOP, and CA teams. A valuable technique may be to conduct periodic, unbiased surveys or opinion polls of the civilian population to determine changes in their perceptions and attitudes.

Security Operations

Protecting Civilians and Critical Infrastructure

9-25. Security for NGOs and civilians may also be an important shaping operation, particularly for stability and civil support operations. Commanders may need to provide security to civil agencies and NGOs located near or operating in the urban area so that these agencies can focus their relief efforts directly to the emergency. Commanders may also need to protect the urban population and critical infrastructure to maintain law and order if the urban area’s security or police forces are nonexistent or incapacitated, or the urban area’s security situation has undergone drastic change (such as the result of a natural disaster) and security or police forces require additional augmentation. (See also the discussion of the legal aspects of Civilians Accompanying the Force in Chapter 10.)

Preserving Resources

9-26. Just as forces may be at risk during urban stability or civil support operations, so may their resources. In urban areas of great need, supplies and equipment are extremely valuable. Criminal elements, insurgent forces, and people in need may try to steal weapons, ammunition, food, construction material, medical supplies, and fuel. Protecting these resources may become a critical shaping operation. Otherwise, Army forces and supporting agencies may lack the resources to accomplish their primary objectives or overall mission.

Prioritize Resources and Efforts

9-27. During UO, commanders will always face limited resources with which to shape the battlefield, conduct their decisive operations, and accomplish their objectives. They must continually prioritize, allocate, and apply those resources to achieve the desired end state. To this end, they may develop an order of merit list for proposed projects and constantly update it over time. To some degree, the local urban population will usually need to be protected and sustained by Army forces. Hence, commanders must tailor their objectives and shape their operations to achieve the greatest good for the largest number.

Commanders first apply the urban fundamental of preserving critical infrastructure to reduce the disruption to the residents’ health and welfare. Second, they apply the urban fundamental of restoring essential services, which includes prioritizing their efforts to provide vital services for the greatest number of inhabitants possible. In operations that include efforts to alleviate human suffering, the criticism for any participating organization is likely to be there is not enough being done or Army forces are not being responsive enough. Therefore, commanders must develop clear measures of effectiveness not only to determine necessary improvements to operational plans but also to demonstrate their Soldiers’ hard work and sacrifice and U.S. commitment to the operation.

Improve the Urban Economy

9-28. When conducting reconstruction and infrastructure repair, commanders should consider using such activities to simultaneously improve the urban economy. Hiring local civilians and organizations to do reconstruction work helps satisfies urban job requirements, may inspire critical elements of the urban society to assume responsibility for the success or failure of urban restoration efforts, and may potentially reduce threat influence by diminishing their civilian sources of aid. Hiring indigenous personnel for short-term projects does not replace the need for long-term economic planning and the development of stable jobs. The overall reconstruction effort must be guided by the commander’s vision of the end state.

However, the commander’s guidance and intent should be broad and expansive enough to allow responsive decision making by subordinate commanders based on their analysis of the urban population’s needs in their assigned AO.

9-10

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Stability and Civil Support Operations

ENGAGE

If there is any lesson to be derived from the work of the regular troops in San Francisco, it is that nothing can take the place of training and discipline, and that self-control and patience are as important as courage.

Brigadier General Frederick Funston

commenting on the Army’s assistance following

the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire

9-29. The focus of the Army is warfighting. Therefore, when Army commanders conduct many urban stability and civil support operations, they must adjust their concept of success. Commanders will most often find themselves in a supporting role and less often responsible for conducting decisive operations.

They must accept this supporting function and capitalize on the professional values they have instilled in each Soldier, particularly the sense of duty to do what needs to be done despite difficulty, danger, and personal hardship. Commanders must also put accomplishing the overall mission ahead of individual desires to take the lead—desire often fulfilled by being the supported rather than supporting commander. In many stability and civil support operations, success may be described as settlement and compromise rather than victory. Yet, the Army’s professionalism and values—combined with inherent adaptability, aggressive coordination, perseverance, and reasonable restraint—will allow Army forces to engage purposefully and dominate during complex urban stability or civil support operations.

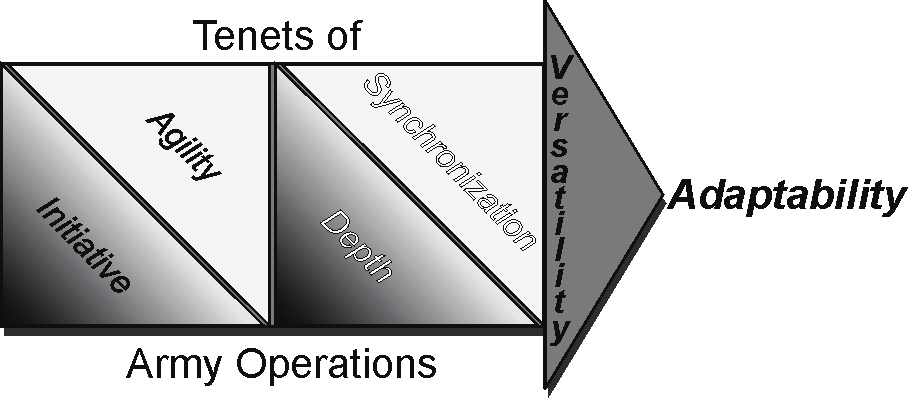

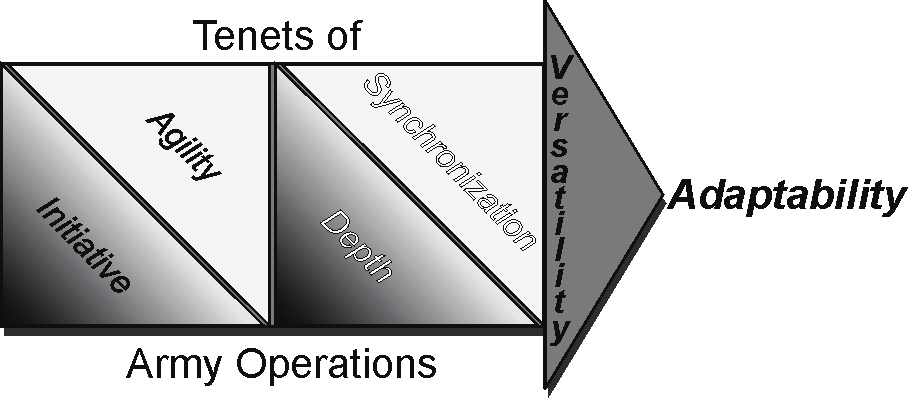

Adaptability

9-30. Adaptability is particularly critical to urban stability or civil support operations because these operations relentlessly present complex

challenges to commanders for which no

prescribed solutions exist. Commanders often

lack the experience and training that provide

the basis for creating the unique solutions

required for these operations. Since the

primary purpose for the Army is to fight and

win the nation’s wars, the challenge then is to

adapt urban warfighting skills to the unique

stability or civil support situation.

Figure 9-3. Adaptability

9-31. Doctrine (joint and Army) provides an inherent cohesion among the leaders of the Army and other services. Still, Army commanders conducting urban stability or civil support operations will often work with and support other agencies that have dissimilar purposes, methods, and professional languages. Army commanders must then capitalize on three of the five doctrinal tenets of Army operations: initiative, agility, and versatility (see figure 9-3 and FM 3-0). Commanders must bend as each situation and the urban environment demand without losing their orientation. They must thoroughly embrace the mission command philosophy of command and control addressed in FM 6-0 and Chapter 5 to encourage and allow subordinates to exercise creative and critical thinking required for planning and executing these UO.

Commanders must also be alert to and recognize “good ideas,” and effective tactics, techniques, and procedures, regardless of their source—other services, coalition partners, governmental and nongovernmental organizations, and even the threat—and adapt them for their own purposes in UO.

9-32. Adaptability also springs from detailed planning that carefully considers and realistically accounts for the extent of stability and civil support operations. Although no plan can account for every contingency and completely eliminate the unexpected, good plans—which include detailed civil considerations—

provide platforms from which to adjust course more readily. Adequate planning allows commanders not only to react more effectively, but also to be forward-thinking and take actions that favorably steer the course of events.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

9-11

Chapter 9

Aggressive Coordination and Synchronization

9-33. In urban stability and civil support operations, the increased number of participants (both military and nonmilitary) and divergent missions and methods create a significant coordination and synchronization challenge. Significant potential for duplicated effort and working at cross-purposes exists. The success of UO often depends on establishing a successful working relationship with all groups operating in the urban area. The absence of unity of command among civil and military organizations does not prevent commanders from influencing other participants not under his direct command through persuasion, good leadership, and innovative ideas.

9-34. Commanders may consider establishing, as necessary, separate organizations for combat operations and for stability operations or civil support operations to increase coordination and enhance local, NGO, and international support. Further, aligning the unit or subordinate units with NGOs may contribute to establishing popular legitimacy for the operation and place greater pressure on threat forces. In some instances, commanders may consider organizing part of their staff around government, administrative, and infrastructure functions that mirror the urban area in which their forces are operating. Development of a mirror urban area organization may give greater legitimacy to the urban government or administration and ease transition of responsibility once the end state is achieved. Commanders must be mindful, however, that local groups seen as allying themselves with Army or coalition authorities will likely experience pressure to demonstrate their independence as established dates for redeployment or other critical events approach. In some instances that demonstration of independence may be violent.

Civil Support and Coordination with Civilian Authorities:

Los Angeles – 1992

During the spring of 1992, Soldiers from the 40th Infantry Division, California National Guard were among the forces deployed to Los Angeles County to assist the

California Highway Patrol, Los Angeles County Sheriffs, and civilian law

enforcement. They worked to quell the riots that were sparked by the “not guilty”

verdicts concerning four police officers who, following a lengthy high-speed chase

through Los Angeles, were accused of brutally beating Rodney King.

Successful accomplishment of this civil support operation was attributed to the

exercise of strong Army leadership and judgment at lower tactical levels, particularly among the unit’s noncommissioned officers. An essential component of combat

power, it was especially critical in executing noncontiguous and decentralized

operations in the compartmented terrain of Los Angeles. As important, however, was

the clear understanding that Army forces were to support civilian law enforcement—

and not the other way around. The 40th Infantry Division aligned its area of

operations with local law enforcement boundaries and relied heavily on police

recommendations for the level at which Soldiers be armed (the need for magazines

to be locked in weapons or rounds chambered).

One incident emphasized the need for coordination of command and control

measures with civilian agencies even at the lowest tactical levels. To civilian law

enforcement and Army forces, the command “Cover me” was interpreted the same:

be prepared to shoot if necessary. However, when a police officer responding to a

complaint of domestic abuse issued that command to an accompanying squad of

Marines, they responded by immediately providing a supporting base of fire that

narrowly missed some children at home. However, the Marines responded as they

had been trained. This command meant something entirely different to them than for

Army Soldiers and civilian law enforcement. Again, coordination at all levels is critical to the success of the operation (see also the vignette in Appendix B).

9-35. In the constraints imposed by METT-TC and operations security (OPSEC), commanders should seek to coordinate all tactical stability operations with other agencies and forces that share the urban environment. Importantly, they should seek to coordinate appropriate information and intelligence sharing 9-12

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Stability and Civil Support Operations

with participating organizations. Commanders must strive to overcome difficulties, such as mutual suspicion, different values and motivations, and varying methods of organization and execution.

Frequently, they must initiate cooperative efforts with participating civilian agencies and determine where their objectives and plans complement or conflict with those agencies. Commanders can then match Army force capabilities to the needs of the supported agencies. In situations leading to many urban civil support operations, confusion may initially make it difficult to ascertain specific priority requirements.

Reconnaissance and liaison elements—heavily weighted with CA, engineers, and health support personnel—may need to be deployed immediately to determine what type of support Army forces provide.

Overall, aggressive coordination will foster trust and make unity of effort possible in urban stability or civil support operations where unity of command is difficult or impossible to achieve.

Perseverance

9-36. The society is a major factor responsible for increasing the overall duration of urban operations. This particularly applies to urban stability operations where success often depends on changing people’s fundamental beliefs and subsequent actions. Modifying behavior requires influence, sometimes with coercion or control, and perseverance. The urban population often must be convinced or persuaded to accept change. Necessary change may take as long as or longer than the evolution of the conflict. Decades of problems and their consequences cannot be immediately corrected. Frequently, the affected segments of the urban society must see that change is lasting and basic problems are being effectively addressed.

9-37. In most stability operations, success will not occur unless the host nation, not Army forces, ultimately prevails. The host urban administration must address the underlying problem or revise its policies toward the disaffected portions of the urban population. Otherwise, apparent successes will be short lived. The UO fundamental of understanding the human dimension is of paramount importance in applying this consideration. After all Army forces, particularly commanders and staff of major operations, understand the society’s history and culture, they can begin to accurately identify the problem, understand root causes, quickly engage and assist key civilian leadership, and, overall, plan and execute successful Army UO.

Reasonable Restraint

9-38. Unlike offensive and defensive operations where commanders seek to apply overwhelming combat power at decisive points, restraint is more essential to success in urban stability and civil support operations. It involves employing combat power selectively, discriminately, and precisely (yet still at decisive points) in accordance with assigned missions and prescribed legal and policy limitations. Similar to the UO fundamentals of minimizing collateral damage and preserving critical infrastructure, restraint entails restrictions on using force. Commanders of major operations should issue or supplement ROE to guide the tactical application of combat power. Excessively or arbitrarily using force is never justified or tolerated by Army forces. Even unintentionally injuring or killing inhabitants and inadvertently destroying their property and infrastructure lessens legitimacy and the urban population’s sympathy and support.

Collateral damage may even cause some inhabitants to become hostile. In urban stability or civil support operations, even force against a violent opponent is minimized. Undue force often leads to commanders applying ever-increasing force to achieve the same results.

9-39. Although restraint is essential, Army forces, primarily during urban stability operations, must always be capable of decisive (albeit in some circumstances, limited) combat operations. This is in accordance with the UO fundamental of maintaining a close combat capability. This capability must be present and visible, yet displayed in a nonthreatening manner. A commander’s intent normally includes demonstrating strength and resolve without provoking an unintended response. Army forces must be capable of moving quickly through the urban area and available on short notice. When necessary, Army forces must be prepared to apply combat power rapidly, forcefully, and decisively to prevent, end, or deter urban confrontations. Keeping this deterrent viable requires readiness, constant training, and rehearsals. It also requires active reconnaissance, superb OPSEC, a combined arms team, and timely and accurate intelligence.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

9-13

Chapter 9

Restraint: An Najaf, Iraq – 2003

On 31 March 2003, during OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM, The 101st Airborne (Air

Assault) Division transitioned from isolating An Najaf—among the holiest places for

Shia Muslims in Iraq and the home of one of their leading holy men, the Grand

Ayatollah Ali Hussein Sistani—to an attack to clear Iraqi fighters from the town. The decision to attack was made in response to increasing attacks against 101st forces

situated near An Najaf and due to alarming reports that the Fedayeen were killing

Iraqi family members to force adult males to fight coalition forces. Since An Najaf had an airfield, control of the town would also allow the 101st to obtain needed

hardstands for their aircraft.

Ultimately, the division used two brigades to attack and clear the town. The 2nd

Brigade Combat Team (BCT) attacked from the north and the 1st BCT—responsible

for the initial penetration—attacked from the southwest. Using tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, and light infantry, the commander of the 1st BCT formed effective combined arms teams supported by artillery and air that successfully fought their way into the city.

On 3 April 2003, Soldiers of TF 2-327 Infantry turned a street corner to face a group of civilian men blocking their way and shouting in Arabic, “God is great.” The crowd quickly grew into hundreds as they mistakenly thought the Soldiers were trying to

capture Sistani and seize the Imam Ali Mosque. Someone in the crowd threw a rock

at the Soldiers, which started a hailstorm of rocks; even the battalion commander

was hit on the head, chest, and the corner of his sunglasses.

Based on information from a Free-Iraqi Fighter accompanying the battalion and his

own observations during the attack, the commander of TF 2-327 believed that most

of the people in An Najaf neither wanted to fight nor obstruct his unit’s efforts.

Consequently, he ordered his Soldiers to position themselves on one knee, smile,

and point their weapons toward the ground. At this gesture, many of the Iraqis

backed off and sat down, enabling the commander to identify the true troublemakers.

He identified eight. In case these agitators were to produce weapons and start to

shoot, the commander wanted to make sure that the remainder of the crowd would

know from where the shooting would originate. Next, he ordered his Soldiers to

withdraw to allow the tension to subside. With his own rifle pointed toward the

ground, the battalion commander bowed to the crowd and led his Soldiers away.

When tempers had calmed, the Grand Ayatollah Sistani issued a decree (fatwa)

calling on the people of Najaf to welcome the American Soldiers.

The attack on An Najaf by the 101st provides an excellent example of well-led

Soldiers capable of understanding cultural differences and possessing the discipline and mental flexibility to transition from the aggressive mindset required for high-intensity urban combat to the restraint essential for the initiation of stability

operations. In his weekly radio address, President George W. Bush commented:

“This gesture of respect helped defuse a dangerous situation and made our peaceful

intentions clear.”

CONSOLIDATE

9-40. As urban operations will often be full spectrum, many of the consolidation activities necessary to secure gains in urban offensive and defensive operations will be applicable to urban stability and civil support operations. However, the greatest obstacles to attaining strategic objectives will come after major urban combat operations. Therefore, emphasis will appropriately shift from actions to ensure the defeat of threat forces to those measures that address the needs of the urban population, manage their perceptions, and allow responsibility to shift from Army forces to legitimate indigenous civilian control (or the intermediate step to other military forces, governmental agencies, and organizations).

9-14

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Stability and Civil Support Operations

Continued Civilian and Infrastructure Protection

9-41. Following urban offensive or defensive operations, there will likely be a need to secure and protect the civilian population and much of the civilian infrastructure from the civilians themselves. After having minimized collateral damage and preserved critical infrastructure, commanders must implement measures to preclude looting and destruction of critical and essential infrastructure by the urban population and civilian-on-civilian violence. This may be as relatively simple as allowing the urban police force to return to work or may be as difficult as hiring, vetting, and training an indigenous police force. In the latter case commanders may need to determine—

z

Number and operability of police stations.

z

Responsibility for recruiting, hiring, training, and equipping the urban security or police force.

The accountable unit, organization, or agency will need to consider a vetting process, suitable salaries and wages, and appropriate training standards.

z

The appropriate responses toward those civilians who threaten, oppose, or harm the new police force.

9-42. Alternatively, civilian security firms (from inside or outside the urban area or country) can provide supplemental protection until indigenous police forces are fully functional. Further, the commander of the major urban operation may plan to manage expected instability primarily with Army forces. Often, this will require larger numbers of infantry, military police, and dismounted forces. Other populace and resource control measures such as curfews may also assist in civilian (including NGOs) and infrastructure protection. Previous shaping operations aimed at improving the loca