concrete industrial buildings and the

fanatical bravery and tenacity of

soldiers and civilians fighting in the

city’s remains (see figure 8-3 on page

8-6).

Beginning in mid-September, the

Soviet command began looking at how

to convert the defense of Stalingrad

into an operational opportunity. During

October and November, the 62nd

Army held on to its toehold in

Stalingrad. While maintaining the

defense of the 62nd Army, the Soviets

secretly began to build up strength on

both flanks of the German 6th Army.

The Germans increased their

vulnerability by securing the German

6th Army’s flanks with less capable

Romanian, Hungarian, and Italian

armies. Also, the 6th Army moved

powerful German divisions into the city

and rotated with German divisions that

were exhausted by urban combat.

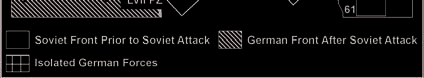

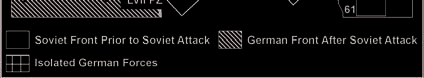

Figure 8-3. German attacks to seize

Stalingrad, September 1942

8-6

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Defensive Operations

On 19 November, the Soviets launched Operation Uranus that attacked two

Romanian armies with seven Soviet armies. Simultaneously, the 8th Russian Army

attacked to aid the 62nd Army in further fixing the German 6th Army. Within five

days, the Soviet armies of the Don Front, Southwest Front, and Stalingrad Front met

near the city of Kalach and sealed the fate of the German 6th Army’s 300,000 troops

in Stalingrad (see figure 8-4).

On the third day of the Soviet offensive, when encirclement seemed inevitable but

not yet complete, the 6th Army commander asked permission to withdraw from the

trap. The German high command denied permission believing that the Army could be

supplied by air and then a renewed

offensive could break through to the

city. On 12 December, the German

LVII Panzer Corps launched an

offensive north to break through to

Stalingrad. This offensive made

progress until another Soviet offensive

on 16 December forced its

cancellation. This ended any hope of

recovering Stalingrad and the 6th

Army. On 31 January 1943, the 6th

Army surrendered after sustaining

losses of almost two-thirds of its

strength. The Soviets took over

100,000 prisoners.

Figure 8-4. Soviet attacks trap German 6th

Army

Many lessons emerge from the successful defense of Stalingrad. Tactically, the

defense showed how using the terrain of a modern industrial city wisely could

increase the combat power of an inferior, defending force and reduce the maneuver

options of a mobile, modern attacking force. Another element in the Soviet’s tactical success was the Germans’ inability to isolate the defenders. The Germans never

threatened the Soviet supply bases east of the Volga and, despite German air

superiority, the Soviets continuously supplied and reinforced the 62nd Army across

the Volga River. Also, Soviet artillery west of the river was able to fire in support of Soviet forces and was never threatened with ground attack.

At the operational level, the Soviets demonstrated a keen understanding of using an

urban area within the context of a mobile defense. The 62nd Army’s stubborn area

defense of Stalingrad drew the bulk of the German combat power into the urban area

where they were fixed by a smaller and quantitatively inferior defending force. This allowed the Soviets to build combat power outside the urban area. The Soviets set

the conditions for a mobile defense by positioning powerful Soviet armor forces in

open terrain outside the urban area against quantitatively inferior German allied

forces. In OPERATION URANUS, the mobile defense’s strike force destroyed the

enemy outside the urban area and trapped the greater part of the best enemy

formations inside the urban area. The trapped units were then subjected to dwindling resources and extensive psychological operations, further isolated into pockets, and defeated in detail.

RETROGRADE

8-25. A retrograde involves organized movement away from the threat. Retrograde operations include withdrawals, delays, and retirements. These defensive operations often occur in an urban environment. The 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

8-7

Chapter 8

urban environment enhances the defending force’s ability to conduct retrograde operations successfully (see figure 8-5).

8-26. The cover and concealment afforded by the

urban environment facilitates withdrawals where

friendly forces attempt to break contact with the

threat and move away. The environment also

restricts threat reconnaissance, which is less able to

detect friendly forces moving out of position, and

presents excellent opportunities for deception

actions. Finally, a small security force’s ability to

remain concealed until contact in the urban

environment significantly slows threat attempts to

regain contact once Army forces have broken

contact and begun to move.

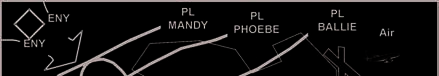

Figure 8-5. Retrograde through an urban area

8-27. The urban environment’s natural cover and concealment, as well as the compartmented effects, facilitates delays. Delays can effectively draw the threat into the urban area for subsequent counterattack or as an integral part of a withdrawal under threat pressure. Delaying units can quickly displace from one covered and concealed position to another; the repositioning options are vast. Compartmented effects force the attacking threat to move on well-defined and easily interdicted routes and limit the threat’s ability to flank or bypass delaying positions.

8-28. The urban area’s transportation and distribution network facilitates retiring forces that are not in contact. Properly used, the urban transportation system can quickly move large forces and associated resources, using port facilities, airfields, railheads, and well-developed road networks.

8-8

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Defensive Operations

URBAN DEFENSIVE CONSIDERATIONS

What is the position about London? I have a very clear view that we should fight every inch of it, and that it would devour quite a large invading army.

Winston Churchill

War in the Streets

8-29. The urban operational framework—understand, shape, engage, consolidate, and transition—provides structure to developing considerations for defensive operations. The considerations can vary depending on the level of war at which the operation is conducted, the type of defense, and the situation. Most issues discussed may, in the right circumstances, apply to both commanders conducting major UO and commanders at lower tactical levels of command.

UNDERSTAND

8-30. The commander defending in the urban area must assess many factors. His mission statement and guidance from higher commanders help him focus his assessment. If the mission is to deny a threat access to port facilities in an urban area, the commander’s assessment will be focused much differently than if the mission is to deny the threat control over the entire urban area. The mission, enemy, terrain and weather, troops and support available, time available, civil considerations (METT TC) structure guides the commander’s assessment. Of these, the impacts of the threat and environment—to include the terrain, weather, and civil considerations—are significant to the commander’s understanding of urban defensive operations.

The Threat

8-31. In the urban defense, a key element is the commander’s understanding of the threat. One of his primary concerns is to determine the attacker’s general scheme, methodology, or concept. Overall, the attacker may take one of two approaches. The most obvious would be a direct approach aimed at seizing the objectives in the area by a frontal attack. A more sophisticated approach would be indirect and begin by isolating Army forces defending the urban area. Innumerable combinations of these two extremes exist, but the threat’s intentions toward the urban area will favor one approach over another. The defending Army commander (whose AO includes but is not limited to the urban area) conducts defensive planning, particularly his allocation of forces, based on this initial assessment of threat intentions. This assessment determines whether the commander’s primary concern is preventing isolation by defeating threat efforts outside the area or defeating a threat attacking the urban area directly. For the higher commander, this assessment determines how he allocates forces in and outside the urban area. For the commander in the urban area, this assessment clarifies threats to sustainment operations and helps shape how he arrays his forces.

The Environment’s Defensive Characteristics

8-32. A second key assessment is the defensive qualities of the urban environment. This understanding, as in any defensive scenario, is based on mission requirements and on a systemic analysis of the terrain in terms of observation and fields of fire, avenues of approach, key terrain, obstacles, and cover and concealment (OAKOC). It is also based on potential chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear and fire hazards that may be present in the urban area. This understanding accounts for the unique characteristics of urban terrain, population, and infrastructure as discussed in Chapter 2.

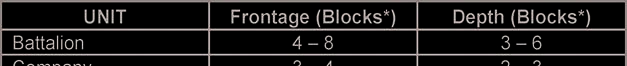

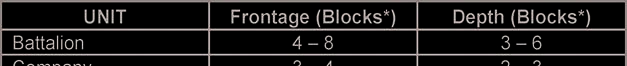

8-33. Generally, units occupy less terrain in urban areas than more open areas. For example, an infantry company, which might occupy 1,500 to 2,000 meters in open terrain, is usually restricted to a frontage of 300 to 800 meters in urban areas. The density of building in the urban area, building sizes and heights, construction materials, rubble, and street patterns will dictate the actual frontage of units; however, for initial planning purposes, figure 8-6 provides approximate frontages and depths for units defending in an urban area.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

8-9

Chapter 8

Figure 8-6. Approximate defensive frontages and depths

SHAPE

8-34. Commanders of a major operation shape the urban battle according to the type of defense they are attempting to conduct. If conducting an area defense or retrograde, they use shaping actions like those for any defensive action. Important shaping actions that apply to all defensive UO include—

z

Preventing or defeating isolation.

z

Separating attacking forces from supporting resources.

z

Creating a mobility advantage.

z

Applying economy of force measures.

z

Effectively managing the urban population.

z

Planning counterattacks.

Preventing or Defeating Isolation

8-35. Failure to prevent isolation of the urban area can rapidly lead to the failure of the entire urban defense. Its importance cannot be overstated. In planning the defense, commanders must anticipate that the threat will attempt to isolate the urban area. Defensive planning addresses in detail defeating threat attacks aimed at isolation of the urban area. Commanders may defeat this effort by allocating sufficient defending forces outside the urban area to prevent its isolation. Defensive information operations (IO) based on deception can also be used to mislead the threat regarding the defensive array in and outside the urban area.

Such information can convince the threat that a direct attack against the urban area is the most favorable approach.

8-36. If the threat has successfully isolated the urban area, commanders of a major operation have several courses of actions. Three options are an exfiltration, a breakout attack by forces defending the urban area, or an attack by forces outside the urban area to relieve the siege. A fourth option combines the last two: counterattacks from both inside and outside the urban area to rupture the isolation (see breakout operations in FM 3-90). Time is critical to the success of either operation. Commanders should plan for both contingencies to ensure rapid execution if necessary. Delay permits threat forces surrounding the urban area to prepare defenses, reorganize their attacking force, retain the initiative, and continue offensive operations. The passage of time also reduces the resources of defending forces and their ability to breakout.

Therefore, commanders and staff of a major operation must vigilantly avoid isolation when Army forces are defending urban areas in their AO.

Separating Attacking Forces from Supporting Resources

8-37. Commanders of the major operation primarily use fires and IO for separating in space and time threat forces attacking the urban area from echelons and resources in support. The purpose of this shaping action is the same as for any conventional area defense. It aims to allow the defending forces to defeat the threat piecemeal as they arrive in the urban area without support and already disrupted by deep fires and IO

against information systems. This separation and disruption of the threat also sets the conditions for a mobile defense if commanders choose to execute that type of defense. These operations also prevent the threat commander from synchronizing and massing his combat power at the decisive point in the close battle.

8-10

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Defensive Operations

8-38. If the urban area is part of a major mobile defense operation, the urban defense becomes the fixing force. Commanders can shape the defense to encourage the threat to attack into the urban area. They can lure the threat using a combination of techniques depending on the situation. They may make the urban area appear only lightly defended while other alternative courses of action appear strongly defended by friendly forces. Placing the bulk of the defending forces in concealed positions well within the urban area and positioning security forces on the periphery of the urban area portray a weak defense. In other situations, the opposite is true. If the urban area is an important objective to the threat, friendly forces can make the urban area appear heavily defended, thus ensuring that he commits sufficient combat power to the urban area to overwhelm the defense. Both cases have the same objective: to cause a major commitment of threat forces in the urban area. Once this commitment is made, the mobile defense striking force attacks and defeats the threat outside the urban area. This isolates the threat in the urban area and facilitates its destruction.

8-39. In the urban tactical battle, many shaping actions mirror those in all defensive operations. The size and complexity of the urban area prevent defending forces from being strong everywhere; shaping operations designed to engage the threat on terms advantageous to the defense have particular importance.

Shaping actions include reconnaissance and security operations, passages of lines, and movement of reserve forces prior to their commitment. In addition, shaping operations critical to urban defense include mobility and countermobility operations, offensive IO, economy of force operations, and population management operations.

Creating a Mobility Advantage

8-40. In urban terrain, countermobility operations can greatly influence bringing the threat into the engagement areas of defending forces. Countermobility operations—based on understanding the urban transportation system, design, and construction characteristics—can be unusually effective (see Chapter 2).

Demolitions can have important implications for creating impassable obstacles in urban canyons as well as for clearing fields of fire where necessary. Careful engineer planning can make the already constrictive terrain virtually impassable to mounted forces where appropriate, thus denying the threat combined arms capabilities. Countermobility operations in urban terrain drastically increase the defense’s ability to shape the attacker’s approach and to increase the combat power ratios in favor of the defense. As with all aspects of UO, countermobility considers collateral damage and the second- and third-order effects of obstacle construction.

8-41. Well-conceived mobility operations in urban terrain can provide defending forces mobility superiority over attacking forces. This is achieved by carefully selecting routes between primary, alternate, and subsequent positions, and for moving reserves and counterattack forces. These routes are reconnoitered, cleared, and marked before the operation. They maximize the cover and concealment characteristics of the terrain. Using demolitions, lanes, and innovative obstacles denies the defense of these same routes.

Applying Economy of Force Measures

8-42. Economy of force is extremely important to effective tactical urban defense. A megalopolis is too large and too easily accessible for defending forces to be strong everywhere. Economy of force enables the defending force to mass effects at decisive points. Forces used in an economy of force role execute security missions and take advantage of obstacles, mobility, and firepower to portray greater combat power than they actually possess. They prevent the threat from determining the actual disposition and strength of the friendly defense. If, contrary to expectations, they are strongly attacked, their mobility—stemming from a mounted maneuver capability, planning, and an intimate knowledge of the terrain—allows them to delay until reserves can meet the threat. Security forces in an economy of force role take position in parts of the urban area where the threat is less likely to attack.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

8-11

Chapter 8

Defensive Combat Power: Suez – 1973

At the end of October, the Israeli Army was in the midst of effective counterattack

against the Egyptian Army. The Israelis had success attacking west across the Suez

Canal. Their armored divisions were attempting to achieve several objectives, to

include destroying Egyptian air defense sites and completing the encirclement of the Egyptian 3rd Army, which was trapped on the canal’s east side.

To completely encircle the Egyptian 3rd Army, the Israelis had to seize all possible crossing sites to it from the canal’s west bank and the Red Sea. Also, as international negotiations towards a cease-fire progressed, the Israeli government wanted to

capture as much Egyptian territory as possible to improve their negotiating position after hostilities.

Consequently, the Israeli Adan Armored Division was tasked to seize the Egyptian

Red Sea port of Suez on the morning of 24 October. A cease-fire was to begin at

0700, and the Israeli intent was to be decisively engaged in the city by that time and then consolidate their position as part of the cease-fire compliance.

The Adan Division plan to seize Suez was a two-part operation. Each of the

division’s armored brigades would have a role. The 460th Brigade would attack west

of the city and complete the city’s encirclement. Simultaneously, the 217th Brigade

would attack in columns of battalions through the city to seize three key intersections in the city. This was in accordance with standard Israeli armored doctrine for fighting in an urban area. The 217th Brigade would seize its objectives through speed,

firepower, and shock action. Once the objectives were seized, infantry and armored

teams would continue attacking from the secured objectives to mop up and destroy

pockets of resistance. The Israeli commanders expected to demoralize the defending

Egyptians—two infantry battalions and one antitank company—by this rapid attack.

The armored division commander was specifically advised by his commander to

avoid a “Stalingrad” situation.

The attack got off to an ominous beginning as mist greatly inhibited a scheduled

aerial bombardment in support of the attack. The 217th Brigade began its attack

without infantry support and was quickly stopped by antitank missiles and antitank

fire. Infantry was quickly integrated into the brigade and the attack resumed.

At the first objective, the Israelis encountered their first problems. A withering barrage of small arms, antitank missiles, and antitank fire hit the lead tank battalion, including direct fire from SU-23 anti-aircraft guns. Virtually all the officers and tank

commanders in the tank battalion were killed or wounded, and several tanks were

destroyed. Disabled vehicles blocked portions of the road, and vehicles that turned

on to secondary roads were ambushed and destroyed. The battalion, however,

successfully fought its way through the first brigade objective and on to the final

brigade objective.

Hastily attached paratroop infantry in company strength were next in column

following the tanks. They were traveling in buses and trucks. As the lead tank

battalion took fire, the paratroopers dismounted, and attempted to secure adjacent

buildings. The tank battalion’s action of fighting through the objective caused the

paratroopers to mount up and also attempt to move through the objective. Because

of their soft skinned vehicles the paratroopers were unable to remain mounted and

again dismounted, assaulted, and secured several buildings that they could defend.

Once inside the buildings, the paratroopers found they were cut off, pinned down,

and unable to evacuate their considerable casualties, which included the battalion

commander. The paratroopers were on the initial brigade objective but were unable

to maneuver and were taking casualties.

A second paratroop company also dismounted and quickly became stalled in house-

to-house fighting. The brigade reconnaissance company in M113 personnel carriers

brought up the rear of the brigade column and lost several vehicles and was also

unable to advance.

8-12

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Defensive Operations

By 1100 the Israeli attack culminated. Elements of the 217th Brigade were on all

three of the brigade’s objectives in the city. However, the armored battalion, which had achieved the deepest penetration, was without infantry support and under

severe antitank fire. Both paratroop companies were isolated and pinned down. In

addition, an attempt to link up with the paratroopers had failed. At the same time, the civilian population of the city began to react. They erected impromptu barriers,

ambushed isolated Israeli troops, and carried supplies and information to Egyptian

forces.

The Israeli division commander ordered the brigade to break contact and fight its way out of the city. The armored battalion was able to fight its way out in daylight. The paratroop companies were forced to wait until darkness and then infiltrated out of the city carrying their wounded with them. Israeli casualties totaled 88 killed and

hundreds wounded in addition to 28 combat vehicles destroyed. Egyptian casualties

were unknown but not believed to be significant.

The fight for Suez effectively demonstrates numerous urban defensive techniques. It

also vividly demonstrates the significant effect on defensive combat power of the

urban environment.

The Egyptian defense demonstrates how the compartmented urban terrain restricts

the mobility and the massing of firepower of armored forces. Trapped in column on

the road, the Israelis were unable to mass fire on particular targets nor effectively synchronize and coordinate their fires. The short-range engagement, also a

characteristic of urban combat, reduced the Israeli armor protection and eliminated

the Israeli armor’s ability to keep out of small arms range. Thus, hand-held antiarmor weapons were more effective in an urban area. Additionally, Egyptian small arms

and sniper fire critically affected Israeli C2 by successfully targeting leaders.

The Egyptian defenders effectively isolated the mounted Israelis by defending and

planning engagement areas in depth. The Egyptians synchronized so that they

engaged the entire Israeli force simultaneously. This forced the Israelis to fight in multiple directions. It also separated the Israeli infantry from the armor and prevented the formation of combined arms teams necessary for effective urban offensive

operations.

Suez also demonstrated how civilians come to the advantage of the defense. After

the battle was joined, the population—by threatening isolated pockets of Israelis and building barricades—helped prevent the Israelis from reorganizing while in contact

and hindered the Israelis breaking contact. The population was also a valuable

source of intelligence for the Egyptians and precluded covert Israeli movement in

daytime.

Suez shows the ability of a well-placed defense in depth to fix a superior force in an urban area. Despite the Israeli commander’s caution to avoid a “Stalingrad,” the

Israeli division, brigade, and battalion commanders were quickly trapped and unable

to easily break contact. Even a successful defense on the perimeter of the city would not have been nearly as effective, as the Israelis would have easily broken contact

once the strength of the defense was recognized.

Another key to the success of the Egyptian defense was the Israelis’ inad