FM 3-06

4-9

Chapter 4

4-36. Vertical structures interrupt line of sight (LOS) and create corridors of visibility along street axes.

The result is thereby shortened acquisition and arming ranges for supporting fires from attack helicopters and subsequently affected engagement techniques and delivery options. Pilots maintain LOS long enough to acquire targets, achieve weapons delivery solutions, and fly to those parameters. For example, tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided heavy antitank missile systems require 65 meters to arm.

Similarly, the Hellfire missile requires at least 500 meters to reliably arm and stabilize on the intended target. Thus, attack helicopters firing from longer ranges actually improve the probability of a hit. Poor weather and heavy smoke and dust rising from urban fires and explosions may hinder target identification, laser designation, and guidance for rotary- and fixed-winged aircraft. Poor air-to-ground communications may also hinder effective use of airpower. The close proximity of friendly units and noncombatants requires units to agree on, thoroughly disseminate, and rehearse clear techniques and procedures for marking target and friendly locations. The ability for ground units to “talk-on” aircraft using a common reference system described earlier helps expedite aerial target acquisition (and helps mitigate potential fratricide). FM 3-06.1 details other aviation TTP in an urban environment.

4-37. The urban environment also affects the type and number of indirect fire weapon systems employed.

Commanders may prefer high-angle fire because of its ability to fire in close proximity to friendly occupied buildings. Tactically, commanders may consider reinforcing units in UO with mortar platoons from reserve units. This will increase the number of systems available to support maneuver units. Unguided Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRSs) may be of limited use in urban areas due to their exceptional destructive capabilities and the potential for collateral damage. However, commanders may use unguided MLRSs to effectively isolate the urban area from outside influence. Commanders may also employ field artillery systems as independent sections, particularly self-propelled systems, in the direct-fire role; decreasing volume and increasing precision of artillery fire helps minimize collateral damage. While discretely applying the effects of high-explosive and concrete-piercing munitions, these self-propelled systems take advantage of the mobility and limited protection of their armored vehicles.

4-38. The urban area may also affect the positioning of artillery. Sufficient space may not exist to place battery or platoon positions with the proper unmasked gun line. This may mandate moving and positioning artillery in sections while still massing fires on specific targets. Commanders must protect artillery systems, particularly when organized into small sections. Threats to artillery include raids and snipers. Therefore, maneuver and firing units will have to place increased emphasis on securing their positions and other appropriate force protection measures.

4-39. The mix of munitions used by indirect fire systems will change somewhat in urban areas. Units will likely request more precision-guided munitions (PGM) for artillery systems to target small enemy positions, such as snipers or machine guns, while limiting collateral damage. Currently, only conventional tube artillery, not mortars, has this capability. However, large expanses of polished, flat reflective surfaces common in urban areas may degrade laser designation for these munitions (as well as attack helicopter PGM). The vertical nature amplifies the geometrical constraints of many precision munitions. Remote designators need to be close enough to accurately designate but far enough away not to be acquired by the PGM during its flight path. PGMs based on the global positioning system (for instance, guided MLRS or the Air Force’s joint direct attack munitions) or other optically guided PGMs may be more effective if urban terrain hinders laser designation.

4-40. The urban environment greatly affects the use of nonprecision munitions. Building height may cause variable time fuses to arm prematurely. Tall buildings may also mask the effects of illumination rounds.

Units may choose not to use dual-purpose conventional munitions if (similar considerations apply to Air Force cluster bombs)—

z

The enemy has several building floors for overhead protection.

z

Dismounted friendly units need rapid access to the area being fired on.

z

Large numbers of civilians will operate in the target areas soon after combat operations have ceased.

4-41. Depending on the building construction, commanders may prohibit or limit illumination, smoke, and other munitions because of fire hazards. In particular instances, they may specifically use them for that effect. Structure fires in an urban area are difficult to control and may affect friendly units. Conventional 4-10

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Understanding the Urban Environment’s Effects on Warfighting Functions and Tactics high-explosive munitions may work best against concrete, steel, stone, and other reinforced structures.

When not used in the direct-fire role, a greater mass of indirect fire is often required to achieve desired effects. Commanders balance firepower and collateral damage since the rubbling caused by massive indirect fires may adversely affect a unit’s ability to maneuver and provide a threat with additional cover and concealment.

4-42. Nonlethal weapons, munitions, and devices can help commanders maintain the desired balance of force protection, mission accomplishment, and safety of noncombatants by expanding the number of options available when deadly force may be problematic. As additional nonlethal capabilities are developed, they are routinely considered for their applicability to UO. In determining their use and employment, commanders, in addition to any previous experience at using these weapons, munitions, and devices, consider—

z

Risk. The use of nonlethal weapons in situations where lethal force is more appropriate may drastically increase the risk to Army forces.

z

Threat Perspective. A threat may interpret the use of nonlethal weapons as a reluctance to use force and embolden him to adopt courses of action that he would not otherwise use.

z

Legal Concerns. Laws or international agreements may restrict or prohibit their use (see Chapter 10).

z

Environmental Concerns. Environmental interests may also limit their use.

z

Public Opinion. The apparent suffering caused by nonlethal weapons, especially when there are no combat casualties with which to contrast it, may arouse adverse public opinion.

PROTECTION

4-43. The protection function includes those tasks and systems that preserve the force so that commanders can apply maximum combat power. Preserving the force includes enhancing survivability and properly planned and executed air and missile defense as well as defensive IO (see IO discussion in Chapter 5) and chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosive (CBRNE) counterproliferation and consequence management activities (see CBRNE discussion in Chapter 9).

Survivability

4-44. Survivability in the urban environment is a significant force multiplier. Properly positioned Army forces can take advantage of the increased survivability afforded by the physical terrain. Even a limited engineer effort can significantly enhance the combat power of small Army forces. In stability operations, properly planned and constructed survivability positions can enable small groups of Soldiers to withstand the assaults of large mobs, sniping, and indirect fire. Well-protected support bases are often critically essential to minimizing casualties during long-term stability operations and can become a key engineer task.

4-45. While executing major combat operations or campaigns, in particular defensive operations, well planned and resourced engineer efforts can enhance the survivability characteristics of the urban area.

These efforts, though still requiring significant time and materiel, can establish defensive strong points more quickly and with greater protection than can be done in more open terrain. Skillfully integrating the strong point into the urban defense greatly increases the overall effectiveness of the defense disproportionately to the number of forces actually occupying the strong point (see Chapter 8).

4-46. Commanders increase survivability by ensuring that all Soldiers have necessary protective equipment and are trained and disciplined in their use. In addition to standard equipment such as helmets, gloves, boots, and chemical protective overgarments, commanders should ensure, as necessary, availability of other protective equipment and material such as—

z

Body armor.

z

Goggles or ballistic eye protection.

z

Knee and elbow protectors.

z

Riot control equipment such as batons, face masks, and shields.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

4-11

Chapter 4

z

Barrier material such as preformed concrete barriers, wire, sandbags, and fencing material.

z

Up-armored or hardened vehicles.

z

Fire extinguishers and other fire-fighting equipment.

z

Immunizations.

4-47. The Army’s urban survivability operations can become complex if the Army is tasked to support survivability operations for civilians. Such operations can range from constructing civil defense shelters or evacuating the population to assisting the population in preparing for or reacting to the use of weapons of mass destruction. However, Army forces are not organized or equipped to support a major urban area’s requirements as well as its own mission needs. Normally, Army forces can render this type of support only as a focused mission using a unique, specially equipped task organization.

Air and Missile Defense

4-48. The air and missile defense protects the force from air surveillance and air and missile attack. This system uses—

z

The careful massing of air and missile defense combat power at points critical to the urban operation.

z

The proper mix of air defense weapon and sensor systems.

z

Matched (or greater) mobility to the supported force.

z

The integration of the air defense plan into the overall urban operation.

z

The integration of Army systems with those of joint and multinational forces.

4-49. Properly planned and executed air and missile defense prevents air threats from interdicting friendly forces and frees the commander to synchronize maneuver and other elements of firepower. Even in a major combat operation or campaign, the enemy will likely have limited air and missile capabilities and so seek to achieve the greatest payoff for the use of these systems. Attacking Army forces and facilities promises the greatest likelihood of achieving results, making urban areas the most likely targets for air and missile attack.

Rotary- and Fixed-Winged Aircraft

4-50. Enemy rotary-wing aircraft can be used in various roles to include air assault, fire support, and combat service support. Some threats may use unmanned aircraft systems to obtain intelligence and target acquisition data on friendly forces. Increased air mobility limitations and targeting difficulties may cause enemy fixed-wing aircraft to target key logistics, C2 nodes, and troop concentrations outside the urban area, simultaneously attacking key infrastructure both in and out of the urban area.

Increased Missile Threat

4-51. The intermediate range missile capability of potential threats has increased to be the most likely air threat to an urban area. Urban areas, particularly friendly or allied, make the most attractive targets because of the sometimes-limited accuracy of these systems. By firing missiles at an urban area, a threat seeks three possible objectives:

z

Inflict casualties and materiel damage on military forces.

z

Inflict casualties and materiel damage on the urban population.

z

Undermine the confidence or trust of the civil population (particularly if allied) in the ability of Army forces to protect them.

4-52. If facing a missile threat, commanders conducting UO work closely with civil authorities (as well as joint and multinational forces) to integrate the Army warning system with civil defense mechanisms.

Similarly, Army forces may support urban agencies reacting to a missile attack with medical and medical evacuation support, survivor recovery and assistance in damaged areas, and crowd control augmentation of local police forces. Before such an attack, Army engineers might assist and advise urban officials on how to construct shelters.

4-12

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Understanding the Urban Environment’s Effects on Warfighting Functions and Tactics

Increased Security of Assets

4-53. When defending against an air or missile threat in a neutral or hostile urban environment, air defense assets are concerned with security. Separating air defense locations from high population and traffic centers, as well as augmenting these positions with defending forces, can prevent or defeat threat efforts to neutralize them. Additionally, increased density of UO means increased concentration of all friendly and enemy systems engaged in air and counter-air operations. This density may increase friend and foe identification challenges, air space management challenges, and the overall risk in the conduct of air operations. Finally, limited air defense assets, difficulties in providing mutual support between systems, potential mobility limitations, and other effects of the urban environment increase the need for (and effectiveness of) a combined arms approach to air defense (see FM 44-8).

SUSTAINMENT

4-54. The sustainment function incorporates support activities and technical service specialties, to include maximizing available urban infrastructure and contracted logistics support. It provides the physical means with which forces operate. Properly conducted, the sustainment function ensures freedom of action, extends operational reach, and prolongs endurance. Commanders conducting sustainment to support full spectrum operations must understand the diverse logistic requirements of units conducting UO. They must also understand how the environment (to include the population) can impact sustainment support. These requirements range from minimal to extensive, requiring Army forces to potentially provide or coordinate all life support essentials to a large urban population.

4-55. Commanders and staffs consider and plan for Army sustainment operations that are based in a major urban area. These operations are located in major urban areas to exploit air- and seaports, maintenance and storage facilities, transportation networks, host-nation contracting opportunities, and labor support. These operations are also UO. The commander gains additional factors to consider from basing the sustainment operation in an urban environment. See Chapter 10 for a detailed discussion of urban sustainment considerations.

COMMAND AND CONTROL

Fighting in a city is much more involved than fighting in the field. Here the “big chiefs”

have practically no influence on the officers and squad leaders commanding the units and subunits.

Soviet General Vasili Chuikov

during the 1942-43 Battle for Stalingrad

4-56. The command and control function is the related tasks and systems that support the commander in exercising authority and direction. The urban environment influences both the commander and his C2

system (which includes INFOSYS). The leader’s ability to physically see the battlefield, his interaction with the human component of the environment, and his intellectual flexibility in the face of change all impact the mission. The C2 system faces difficulties placed on the tactical Internet and system hardware by the urban environment, by the increased volume of information, and by requirements to support the dynamic decision making necessary to execute successful UO.

Unity of Command

4-57. Although severely challenged, the principle of unity of command remains essential to UO. However, the number of tasks and the size of the urban area often require that Army forces operate noncontiguously.

Noncontiguous operations stress the C2 system and challenge the commander’s ability to unify the actions of his subordinates, apply the full force of his combat power, and achieve success. To apply this crucial principle in an urban environment requires centralized planning, mission orders, and highly decentralized execution. The method of C2 that best supports UO is mission command (see FM 6-0). Mission command permits subordinates to be innovative and operate independently according to clear orders and intent as well as clearly articulated ROE. These orders and ROE guide subordinates to make the right decision when facing—

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

4-13

Chapter 4

z

A determined, resolute, and adaptive threat.

z

A complex, multidimensional battlefield.

z

Intermittent or complete loss of communications.

z

Numerous potentially hostile civilians close to military operations.

z

The constant critique of the media and military pundits.

4-58. Decentralized execution allows commanders to focus on the overall situation—a situation that requires constant assessment and coordination with other forces and agencies—instead of the numerous details of lower-level tactical situations. Fundamentally, this concept of C2 requires commanders who can accept risk and trust in the initiative, judgment, and tactical and technical competence of their subordinate leaders. Many times, it requires commanders to exercise a degree of patience as subordinate commanders and leaders apply mental agility to novel situations.

Political and Media Impact

4-59. Commanders of a major operation consider how the need to maintain a heightened awareness of the political situation may affect their exercise of C2. A magnified political awareness and media sensitivity may create a desire to micromanage and rely solely on detailed command. Reliance on this method may create tactical leaders afraid to act decisively and with speed and determination—waiting instead for expected guidance from a higher-level commander. Threats may capitalize on this hesitation by conducting operations faster than Army forces can react. Mission orders that express the overarching political objectives and the impact of inappropriate actions, combined with training and trust, will decrease the need for detailed command. Leaders must reduce a complex political concept to its simplest form, particularly at the small-unit level. Even a basic understanding will help curtail potentially damaging political actions and enable subordinates to make the often instantaneous decisions required in UO—decisions that support military and political objectives.

Commander’s Visualization

I heard small-arms fire and RPG explosions and felt shrapnel hit the vehicle…. Land navigation at this time was impossible; every time I tried to look out, I was thrown in a different direction…. At this time, I was totally disoriented and had not realized we were on our own.

Captain Mark Hollis

“Platoon Under Fire”

4-60. Leaders at all levels need to see the battlefield to lead Soldiers, make effective decisions, and give direction. Sensors and other surveillance and reconnaissance assets alone cannot provide all the information regarding the urban environment that commanders will need. The focus of lead elements narrows rapidly once in contact with a hostile force limiting their assessment to the local area. Therefore, tactical commanders will not be able to observe operations from long, stand-off ranges. Their personal observation remains as critical in urban areas as elsewhere and helps to preclude commanders from demanding their subordinates accomplish a task or advance at a rate inconsistent with the immediate situation. In urban offensive and defensive operations, seeing the battlefield requires that commanders move themselves and their command posts forward to positions that may be more exposed to risk. Thus, commanders modify their C2 system capabilities to make them smaller, reduce their signature, and increase their mobility. Because of the greater threat to C2, security efforts may be more intense.

4-61. In stability operations, commanders often intervene personally to reassure the urban population and community and faction leaders about the intentions of Army forces. In these type operations, threats may attack leaders to gain the greatest payoff with the least expenditure of resources. Commanders carefully evaluate risk and potential benefits of such exposure. These risks however, cannot stop them from seeing the battlefield, personally intervening in situations as appropriate, and leading their Soldiers.

4-62. Commander’s visualization also requires having an accurate understanding of friendly and enemy locations, detailed maps, other appropriate intelligence products, and INFOSYS that accurately depict the urban environment and help establish a COP. The reliability of these items is as important to planning 4-14

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Understanding the Urban Environment’s Effects on Warfighting Functions and Tactics major operations as it is to tactical-level operations. The commander of the major operation ensure that subordinate tactical-level commanders have the necessary products to achieve accurate situational understanding and dominate the urban environment as subordinate commands often lack the personnel or assets to develop these products. Frequently, satellite or aerial imagery is requested to compensate for the drastic changes that can occur due to UO, natural disasters, and outdated or imprecise maps. (Even maps developed and maintained by urban area’s administrative activities may not be up-to-date. Extensive and continually expanding shantytowns, for example, may not be mapped at all. Maps may have even been purposefully distorted or critical detail intentionally omitted. The systems used to transliterate some languages such as Arabic and Chinese to Anglicized alphabets often result in the same location being spelled several—and frequently considerably different—ways. Maps may also assign names to features that are completely different than those used by locals to refer to them.)

4-63. Other critical intelligence products needed in the COP include overlays or gridded reference graphics. (Whenever possible, gridded reference graphics should conform to standard military grid reference system formats to reduce the probability of error when entering target coordinates into targeting systems that use global positioning systems.) These products should be developed and distributed to all participants prior to the UO. Overall, their focus should be on ease of reference and usefulness for all forces—ground and air (see Appendix B). Overlays and graphics can also portray important societal information or urban infrastructure, such as—

z

Religious, ethnic, racial, or other significant and identifiable social divisions.

z

Locations of police, fire, and emergency medical services and their boundaries or zones of coverage.

z

Protected structures such as places of worship, hospitals, or other historical and culturally significant buildings or locations.

z

Underground subway, tunnel, sewer, or water systems.

z

Bridges, elevated roadways, and rail lines.

z

Electrical generation (to include nuclear) and gas storage and production facilities and their distribution lines.

z

Water and sewage treatment facilities.

z

Telephone exchanges and television and radio stations.

z

Toxic industrial material locations.

Mental Flexibility

4-64. Commanders conducting UO must remain mentally flexible. Situations can change rapidly because of the complexity of the human dimension. Typical of the change is a stability operation that suddenly requires the use of force. Commanders must be capable of quickly adjusting their mental focus from a noncombat to combat situation. Equally important is dealing with populations during combat operations.

Consequently, commanders must also be capable of rapidly adjusting plans and orders for sudden stability or civil support tasks that emerge during or soon after a combat mission. In developing their vision, commanders must consider the second- and third-order effects of UO.

Information Systems

4-65. The urban environment also challenges INFOSYS that support the commander, especially communications. Urban structures, materials, densities, and configurations (such as urban canyons) and power constraints associated with man-portable radios significantly degrade frequency modulation (FM) communications. This causes problems at brigade-level and below where commanders rely heavily on constant FM radio contact with subordinates. Tactical communication problems might also cause an inability to maintain a COP, to give orders and guidance, to request support, or to coordinate and synchronize elements of the combined arms team. Communication problems in urban areas can prevent the achievement of information superiority and contribute directly to mission failure. In UO, allocating critical or high-value communication assets will be significant and essential to the main effort.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

4-15

Chapter 4

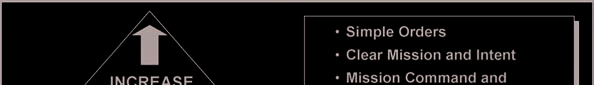

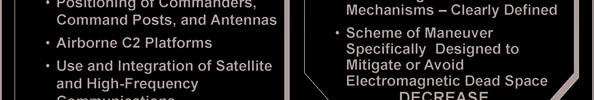

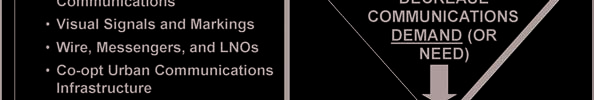

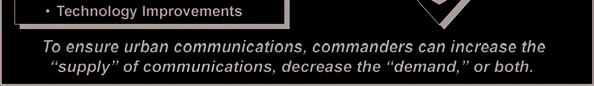

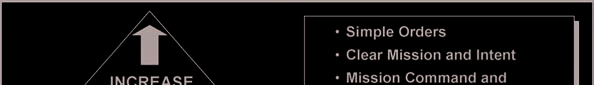

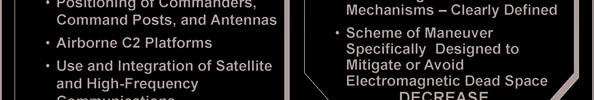

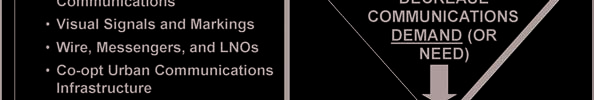

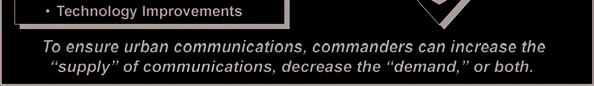

4-66. In an urban environment, units and staffs properly prepare for and mitigate the communication problems in urban areas (see figure 4-3). Adequate communications, in most cases, are ensured by—

z

Training in and use of retransmission and relay sites and equipment, which may include unmanned aircraft systems (UAS).

z

Airborne command posts, satellite communications, high-frequency radios, and other redundant communication platforms and systems.

z

Careful positioning of commanders, command posts, and antennas to take advantage of urban terrain characteristics.

z

Detailed communications analysis for movement from one AO to another due to the likely density of units operating in the urban environment.

Figure 4-3. Methods to overcome urban communications challenges

4-67. Standing operating procedures (SOPs) for visual markings (both day and night) may assist in command and control. These SOPs indicate unit locations and other essential information. They coordinate with units across common boundaries. Given adequate consideration to limitations on multinational capabilities, these SOPs may assist in command and control and preclude fratricide inciden