decision-making abilities.

Figure 4-5. Urban understanding and

decision making

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

4-19

This page intentionally left blank.

Chapter 5

Contemplating Urban Operations

We based all our further calculations on the most unfavorable assumptions: the

inevitability of heavy and prolonged fighting in the streets of Berlin, the possibility of German counter-attacks from outside the ring of encirclement from the west and southwest, restoration of the enemy’s defence to the west of Berlin and the consequent need to continue the offensive.

General of the Army, S. M. Shtemenko

describing operational level planning for taking Berlin

The Soviet General Staff at War

In any potential situation and in any area, Army commanders will likely need to

assess and understand the relevance and impact of one or more urban areas on their

operations. They will also need to determine whether full spectrum urban operations

(UO) will be essential to mission accomplishment. UO may be the commander’s sole

focus or only one of several tasks nested in an even larger operation. Although UO

potentially can be conducted as a single battle, engagement, or strike, they will more often be conducted as a major operation requiring joint resources. Such actions result from the increasing sizes of urban areas. Army commanders of a major urban operation must then ensure that UO clearly support the operational objectives of the joint force commander (JFC), requesting and appropriately integrating critical joint

resources. Whether the urban operation is the major operation itself or one of many

tasks in a larger operation, Army commanders must understand and thoroughly shape

the conditions so subordinate tactical commanders can engage and dominate in this

complex environment.

A major operation is a series of tactical actions (battles, engagements, strikes) conducted by various combat forces of a single or several services, coordinated in time and place, to accomplish operational, and sometimes strategic objectives in an operational area.

DETERMINING THE NECESSITY OF URBAN OPERATIONS

5-1. Early in planning, commanders of a major operation must address the necessity and feasibility of conducting operations in urban areas located throughout their areas of operations (AOs). Chapter 1 discussed strategic and operational considerations that compel forces to operate in urban areas. These reasons include the location and intent of the threat force; critical infrastructure or capabilities that are operationally or strategically valuable; the geographic location of an urban area; and the area’s political, economic, or cultural significance. Additionally, humanitarian concerns may require the control of an urban area or necessitate operations within it. Several considerations exist, however, that may make UO unnecessary, unwarranted, or prohibitively inefficient. When determining whether to operate in an urban environment, commanders must consider the operational (and accidental) risks and balance them with mission benefits.

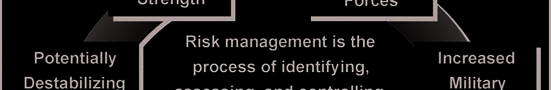

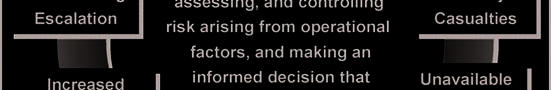

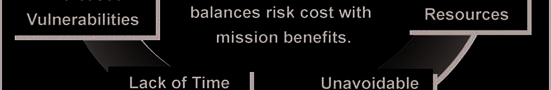

The factors shown in Figure 5-1 highlight some measures to evaluate the risks associated with UO.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

5-1

Chapter 5

Figure 5-1. Risk management and the associated risks with urban operations

INADEQUATE FORCE STRENGTH

5-2. When facing prospective UO, commanders must consider if they have the necessary troops available to conduct the operation properly and within acceptable risk. Under normal circumstances, large urban areas require many forces merely to establish control. The New York City police department has over forty thousand officers and hundreds of support staff simply to conduct peacetime law enforcement. Major UO, particularly those that are opposed, will often require a significant number of forces. Offensive missions, for example, can require three to five times greater troop density than for similar missions in open terrain.

If commanders lack sufficient force to conduct effective operations, they may postpone or consider not initiating those operations until they have the necessary strength. Commanders should also add to their analysis the requirements for troop strength elsewhere in the AO. Additionally, commanders must consider the number (and type) of forces required to make the transition from urban offensive and defensive to stability or civil support operations when determining overall force requirements—not just the number of forces required to realize objectives for major combat operations.

INCORRECT BALANCE OF FORCES

5-3. Along with force strength, commanders must consider the type and balance of forces available. This consideration includes an assessment of their level of training in urban operations. Generally, UO put a premium on well-trained, dismounted infantry units. The operational or tactical necessity to clear threat forces from the dense urban environment, hold hard-won terrain, and interact with the urban population greatly increase dismounted requirements. Therefore, Army forces conducting UO are often force tailored to include a larger infantry component. In addition, special operations forces (SOF) are invaluable in UO.

SOF include psychological operations (PSYOP) and civil affairs (CA) forces. They should always be considered as part of the task organization.

5-4. UO must include combined arms to ensure tactical success in combat. Although masses of heavy forces may not be required, successful UO require the complementary effects of all Army forces. Even if an urban operation is unlikely to involve offensive and defensive operations, armor, combat engineers, and field artillery may be essential to mobility and force protection. In urban stability and civil support operations, successful mission accomplishment requires more robust CA organizations. They are also valuable in urban offensive and defensive operations. While commanders may have sufficient combat and combat support forces, they may lack enough sustainment forces to provide the support necessary to maintain the 5-2

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Contemplating Urban Operations

tempo. Again, commanders without balanced types of forces, to include their proficiency in operating in urban environments, should consider alternatives to UO or delaying UO until proper force types are trained and available in sufficient numbers.

INCREASED MILITARY CASUALTIES

5-5. Casualties in UO are more likely than in operations in other environments. In urban offense and defense, friendly and threat forces often engage at close range with little space to maneuver. The urban terrain provides numerous advantages to the urban defender; higher casualties occur among troops on the offensive, where frontal assaults may be the only tactical option. Conversely, defenders with limited ability to withdraw can also suffer high casualties when isolated and attacked. Casualties can be more difficult to prevent in urban stability operations because of the dense complex terrain, the close proximity of the urban population, and the possible difficulty in distinguishing friend from foe. The potential for high casualties and the subsequent need for casualty evacuation under difficult circumstances make the positioning and availability of adequate medical resources another important consideration. Additionally, high-intensity urban combat and the potential for increased stress casualties may require additional units to allow for adequate unit rotations so that Soldiers receive the rest they require.

5-6. Though casualties occur in all operations, commanders should recognize the likelihood of more casualties during large-scale or high-intensity UO. During the battle for Hue in 1968, for example, many company-size units suffered more than 60 percent casualties in only a few days of offensive operations.

Commanders conducting urban stability operations must know the casualty risk and how it relates to national and strategic objectives. While a lower risk normally exists in stability operations than in offensive and defensive operations, just one casualty may adversely impact the success of the stability mission. A realistic understanding of the risk and the nature of casualties resulting from UO critically affect the decision-making process. If commanders assess the casualty risk as high, they must ensure that their higher headquarters understands their assessment and that the objectives sought within the urban area are commensurate with the anticipated risk.

UNAVAILABLE RESOURCES

5-7. Offensive and defensive operations in an urban environment put a premium on certain types of munitions and equipment. Forces may want to use vast amounts of precision munitions in the urban environment. At the tactical level, they will likely use more munitions than during operations in other environments. These munitions include—

z

Grenades (fragmentation, concussion, stun, riot control, and smoke).

z

Mortar ammunition (due to its rate of fire, responsiveness, and high-angle fire characteristic).

z

Explosives.

z

Small arms.

5-8. Soldiers need access to special equipment necessary to execute small-unit tactics effectively. In urban stability and civil support operations, this equipment may include antiriot gear, such as batons, protective clothing, and other nonlethal crowd-control devices. In urban offensive and defensive operations, special equipment can include sniper rifles, scaling ladders, knee and elbow pads, and breaching equipment such as door busters, bolt cutters, and sledgehammers. Soldiers can conduct UO with standard clothing and military equipment. However, failure to equip them with the right types and quantities of munitions and special equipment will make mission success more difficult and costly. When commanders consider whether to conduct UO, they must evaluate the ability of logistics to provide the necessary resources (see Chapter 10). Considerations must include the ability to supply all Soldiers regardless of branch or military occupational specialty with urban-specific equipment.

UNAVOIDABLE COLLATERAL DAMAGE

5-9. UO require an expanded view of risk assessment. When considering risk to Army, joint, and multinational forces, commanders must also analyze the risk to the area’s population and infrastructure.

This comprehensive analysis includes the second- and third-order effects of significant civil casualties and 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

5-3

Chapter 5

infrastructure damage. Collateral damage can influence world and domestic opinion of military operations and thus directly affect ongoing operations. It also influences the postconflict physical environment and attitudes of the population. Negative impressions of the civilian population caused by collateral damage can take generations to overcome. Destroying an urban area to save it is not a viable course of action for Army commanders. The density of civilian populations in urban areas and the multidimensional nature of the environment make it more likely that even accurate attacks with precision weapons will injure noncombatants. Unavoidable collateral damage of sufficient magnitude may justify avoiding UO, which, though it may be tactically successful, may run counter to national and strategic objectives.

LACK OF TIME AND LOSS OF MOMENTUM

5-10. Commanders conducting major operations must analyze the time required to conduct UO

successfully. UO can be time consuming and can require larger quantities of resources. The density of the environment, the need for additional time to conduct a thorough reconnaissance, the additional stress and physical exertion imposed on Army forces operating in urban areas, and the potential requirements to care for the needs of the urban population consume time and slow momentum. Commanders cannot permit UO

conducted as a shaping operation to divert resources from the decisive operation. Nor can they allow UO to interrupt critical time lines, unnecessarily slow tempo, or delay the overall operation. Threat forces may conduct UO with the primary purpose of causing these effects. Commanders must recognize that time generally works against political and military objectives and, hence, they must develop plans and operations to avoid or minimize UO that might unacceptably delay or disrupt the larger, decisive operation.

Once commanders achieve major combat objectives, however, they will likely need to shift resources and focus on the urban areas that they previously isolated and bypassed.

INCREASED VULNERABILITIES

5-11. Commanders must weigh the potential for increased vulnerabilities when executing UO. The density of the environment makes protection (safety, field discipline, force protection, and especially fratricide avoidance) much more difficult. Forces operating in a large urban area increase their risk of isolation and defeat in detail. Joint capabilities, such as air power, may work less effectively to support a close urban battle than in some other environments. Thus, responding to unexpected situations or augmenting disadvantageous force ratios when applying joint capabilities is significantly more difficult. Although organized, trained, and equipped for success in any environment, the Army vulnerability to weapons of mass destruction (WMD) increases when forces concentrate to conduct UO. Commanders may consider not committing forces or limiting the size of a force committed to an urban area because of increased vulnerability to (and likelihood of) attack by WMD.

5-12. Fratricide avoidance is a matter of concern for commanders in all operations. The complex urban terrain and density of participating forces coupled with typical battlefield effects—smoke, dust, burning fires—and weather effects—fog, snow, rain, and clouds—immensely increase the potential for urban fratricide. Additionally, safety requirements make it difficult to fully replicate training conditions that allow leaders to become more aware of the conditions that contribute to fratricide. The effects of fratricide can be devastating to UO and spread deeply within the Army force. Critical effects include—

z

Needless loss of combat power.

z

Decreased confidence in leadership, weapons, and equipment. These lead to a loss in initiative and aggressiveness, failure to use supporting combat systems, and hesitation to conduct limited visibility operations.

z

Disrupted operations and decreased tempo.

z

General degradation of cohesion and morale.

5-13. Therefore, commanders should increase fratricide awareness and emphasis on prevention measures during UO. Causes can be procedural, technical, or a combination of the two and include—

z

Combat identification failures due to poor situational understanding, lack of communication, failure to effectively coordinate, and short engagement ranges coupled with the need for quick reaction.

5-4

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Contemplating Urban Operations

z

Location errors involving either the target or enemy forces due to poor situational

understanding.

z

Inappropriate command and control and fire support coordinating measures; a failure to receive, understand, or adhere to these measures.

z

Imprecise weapons and munitions effects such as, an antitank round that penetrates several walls before exploding near friendly forces.

Exacerbating these difficulties will be the likelihood of Army forces conducting operations with (or within proximity of) SOF, coalition forces, and indigenous security forces including local police. (During OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM, the head of the Australian Defence Forces SOF in Iraq made it a point to carefully coordinate with U.S. Army forces—down to the company level—whenever his personnel would be in an American AO. He felt the danger of fratricide was a much greater risk than the loss of operational security.)

POTENTIALLY DESTABILIZING ESCALATION

5-14. In the urban environment, Army forces cannot avoid close contact with enemy forces and civilians that may potentially become hostiles. In urban stability and civil support operations, commanders should consider the chance of this contact escalating into confrontation and violence, which may become destabilizing. This consideration may delay, limit, or altogether preclude UO using Army forces.

CONSIDER ALTERNATIVES AND RISK REDUCTION MEASURES

5-15. Since UO are often high risk, commanders should consider courses of action that provide alternatives. When the objective of an urban operation is a facility, commanders should consider replicating that facility outside of the urban area. For example, a critical requirement for an airfield to sustain operations may lead commanders to consider UO to seize or secure one located in an urban area.

However, if adequate resources exist (especially time and adequate general engineering support), Army forces may build an airfield outside of the urban area and eliminate the need to conduct the urban operation. Similarly, logistics over-the-shore operations may be an alternative to seizing a port facility. In some situations, the objective of UO may be to protect a political organization such as a government.

Relocating the government, its institutions, and its personnel to a safer area may be possible. Commanders can also design an operation to avoid an urban area. For example, if an urban area dominates a particular avenue of approach, use a different avenue of approach. Using a different avenue of approach differs from isolating and bypassing because the entire operation specifically makes the urban area irrelevant.

5-16. If commanders execute UO, they must assess potential hazards, and then they develop controls to either eliminate or reduce the risks to Army forces. The first means to offset risk is always to ensure a thorough understanding of the urban environment and its effects on operations by all members of the force.

Other measures to mitigate risk may include—

z

Detailed planning to include thorough intelligence preparation of the battlefield and the development of appropriate branches and sequels.

z

Integrated, accurate, and timely intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR).

z

Clear missions and intent, which includes a well-articulated end state that looks beyond the cessation of combat operations.

z

Sufficient reserves and rotation of forces.

z

Vigilant physical security precautions to include increased use of barriers and other defenses, particularly when urban areas are used as support areas.

z

Operative communications and other information systems (INFOSYS).

z

Effective populace and resources control measures.

z

Comprehensive and flexible rules of engagement (ROE) continuously reviewed to ensure they remain adequate for the situation.

z

Sufficient control measures (which often include a common urban reference system) and standard marking and identification techniques that adequately consider limited visibility concerns for both air and ground forces. Measures should allow commanders to satisfactorily 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

5-5

Chapter 5

control UO and minimize fratricide without unreasonably restricting subordinate commanders’

ability to accomplish assigned missions. Commanders must ensure that all subordinate units thoroughly disseminate any approved nonstandard reference systems.

z

Proper targeting procedures (including effective fire support coordinating measures and a streamlined legal review of targets), positive identification of targets, and controlled clearance of fires. The goal is achievement of precise (yet rapid) effects with both lethal and nonlethal means. In close air support, positive air-to-ground communications are essential to coordinate and authenticate markings.

z

Well-synchronized information operations (IO) that begin before introducing Army forces into the urban environment and well through transition. Commanders should emphasize vigilant operations security (OPSEC) particularly when operating closely with the media,

nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and elements of the civilian population.

z

Active and effective integrating, synchronizing, and coordinating among all forces, agencies, and organizations involved in the operation. Commanders should allow adequate planning and rehearsal time for subordinates.

z

Responsive, sustainable, and flexible urban sustainment.

z

Forces well trained in joint, interagency, multinational, and combined arms UO.

z

The creation of adaptable, learning organizations. This requires thorough after-action analyses conducted during actual operations as well as after training exercises. In addition to official Army sites (such as the Center for Army Lessons Learned and the Battle Command Knowledge System), commanders must create a unit-level system to allow hard-won, lessons learned and tactics developed to be immediately passed on to other units and soldiers—even in the midst of an operation. This system may be technology-based, procedural, or both. (During OPERATION

IRAQI FREEDOM, the 1st Cavalry Division developed an effective web-based knowledge

network—called CAVNET—that allowed them to actively capture and share lessons learned among subordinate units.)

INTEGRATION INTO LAND OPERATIONS

5-17. The commander of the major operation, after determining that urban operations are required, will then integrate the urban operation into his overall operation. He does this by articulating his intent and concept for the urban operation to his subordinates. The commander of the major operation must also set the conditions for successful tactical urban operations by his subordinates. He should define ROE, focus ISR efforts, task organize his capabilities, ensure information superiority, design the operational framework, and initiate and sustain effective coordination with other agencies and organizations (see FM

6-0).

CONCEPT OF THE OPERATION

5-18. The commander’s concept of the operation should address all operationally important urban areas in his AO. It should also articulate his vision of the urban operation through directions to his staff and subordinates. Subordinate commanders should address urban areas that the higher commander does not specifically address. The commander’s concept should discuss each urban area in terms of task and purpose (see FM 5-0). The commander should also describes his vision of the situation’s end state in terms of—

z

The threat.

z

The urban environment (terrain, society, and infrastructure).

z

Friendly forces.

z

The conditions necessary to transition control of urban areas within his AO to another agency or back to legitimate civilian control.

5-6

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Contemplating Urban Operations

RULES OF ENGAGEMENT

5-19. National- or joint-level command authorities may develop urban-specific ROE. If not, Army commanders, as part of their assessment, must determine if urban-specific ROE are required for their situation and provide supplemental ROE. However, commanders must forward any conflicts or incongruities to their higher headquarters for immediate resolution.

5-20. Developing effective ROE relies on thoroughly understanding the national and strategic environment and objectives. It also relies on understanding how to conduct urban operations at the tactical level including weapons effects. For example, broad ROE may result in significant collateral damage and civilian casualties. Even in a major operation or campaign, significant collateral damage caused during UO

can make postcombat operations difficult. Such damage may even change national and international public opinion or threaten the achievement of national and strategic objectives. In contrast, restrictive ROE can hamper tactical operations causing mission failure, higher friendly casualties, or both. ROE are often part of essential elements of friendly information (EEFI), protected to reduce the potential for threat exploitation. Even in a limited urban operation, ROE will frequently need to change as circumstances warrant. Therefore, commanders should plan ROE “branches” for anticipated changes in the operational environment.

5-21. In urban operations, ROE are flexible, detailed, and understandable. They should preclude the indiscriminate use of deadly force while allowing soldiers latitude to finish the mission and defend themselves. ROE should recognize that the urban area is not homogenous and may vary according to the key elements of the threat and environment: terrain, society, and infrastructure. To be effective, ROE are consistent throughout the force (an increased challenge in multinational urban operations), and soldiers are thoroughly trained and familiar with them.

Enemy Considerations

5-22. The nature of an urban enemy affects ROE as well. Commanders must consider the type of enemy weapon systems, the degree of defensive preparation, the ability to target enemy vulnerabilities with precision systems, and the ability to distinguish combatant from noncombatant.

Terrain Considerations

5-23. ROE may vary according to the terrain or physical attributes of an urban area. Physical factors may drive the ROE to preclude certain types of munitions. For example, if the construction of a portion of the area is sensitive to fire, then ROE may preclude using incendiary munitions in that area. The ROE may lift this prohibition when units move into areas of masonry construction. Toxic industrial chemicals or radiological contaminants in an industrial area may also affect ROE.

Societal Considerations

5-24. The societal or human dimension of the urban environment will often affect ROE the most.

Commanders must base the ROE development on a thorough understanding of the civilian population and threat. They evaluate the loyalty of the population, its dynamic involvement in activities that affects the operation, and its size and physical location. A population that is present and supports Army forces will likely elicit more restrictive ROE than a hostile population actively supporting forces opposing the Army forces. A neutral population, not actively involved in behavior affecting Army forces, supports consideration of more restrictive ROE. In all cases, ROE conforms to the law of war. However, ROE may be much more restrictive than the law of war requires.

5-25. The location of the population also affects ROE. The evacuation or consolidation of noncombatants into controlled, safe areas may result in less restrictive ROE. A U.S. or allied population that remains in the urban area conducting routine business in and amongst Army forces during noncombat UO will normally require