CHAPTER V

Sources

One of the many questions that are frequently asked of the archeologist, and one that is most difficult to answer in a few brief words, concerns the source of his material. There is a sort of mystery that hovers over this modern calling which intrigues the fancy of the average layman. When an archeologist begins to dig in some barren waste of sand and comes upon a buried city that has been missing from the history of men for multiplied centuries, it impresses the casual observer as magic of the blackest kind. There is, however, nothing supernatural or uncommon about these discoveries, although the element of chance does enter in to a minor extent. Some of the greatest and most prolific fields we personally have investigated were brought to our attention when the plow of a farmer cast up a human skull and focussed attention upon that particular field. Generally, however, the sources of archeology are uncovered by hard, patient, painstaking labor.

When an able prospector starts out in his search for gold, he is guided by certain known factors that have been derived from the experience of generations. Panning his way up a stream-bed, the keen-eyed hunter of fortune tests every spot that previous experience had taught him might be profitable. He may labor at one thousand barren sites before he strikes gold. If he is in a mountainous country and the placer deposits are not rich enough to pay him to tarry on the spot where the first discovery was made, he will work his way on up the stream, testing site after site for increasing values. If the show of color in his pan suddenly ceases, he knows that he has passed the sources of these wandering fragments. He then goes back to the last point where he found traces of gold and then begins to search the side canyons and branch streams that lead into the main channel. In this way he traces his path step by step to the ledge from which the gold originally came. After laboring weary months, or even years, with heart-breaking disappointment and grim, hard work, if he is fortunate he announces a discovery. The thoughtless immediately credit his good fortune to the goddess of luck and wonder why they also could not be blessed that way.

This illustration is an exact picture of the manner in which archeologists go about their business. There are certain sites that experience has taught us should be profitable to investigate. The region is carefully combed for surface indications. These may be such things as shards of pottery, arrowheads, fragmentary bones, or any of the ordinary debris that indicates a site of human habitation or burial. When the surface indications suggest the probability of a real find, then the digging commences. Most of our great discoveries are made only after months, and even years, of painstaking survey. These surveys must be made by men who are expert in the interpretation of surface indications and fragmentary evidences. Thus it is at once apparent that there is really nothing supernatural or magical about this sober craft; it is scientific in its procedure. There is no “doodle-bug” for archeology such as is sometimes used by those who are found around the fringe of geology.

It must be remembered that the orientals differed greatly in their building methods from the occidentals. It is customary among us to excavate to bed rock before we lay the foundation for a building. The orientals, however, began to build right on the surface of any site that suited their fancy. For instance, a wandering tribe of nomads desiring to settle either temporarily or permanently, would pick out a hill that was more easily defended than a level site would be. Upon its crest, they built their houses and generally fenced the scene for the purposes of defense. Within these fortifying walls they dwelt in more or less security until they became rich enough to be robbed. It would not be long, however, under the brutal law of might that prevailed in those ancient days, before some marauding band would overrun that site with fire and sword. The walls would be breached or cast down and the inhabitants put to sword or carried away into slavery. Usually fire would sweep the homes of this once contented people and their memory would soon be forgotten.

To one who has seen the sand storms of the East, the rest of the story is self-evident. Even in our own times and in our own land, we have seen what can happen when drought and wind begin to move the surface of a country and make the efforts of man fruitless and unavailing. When men lived in these sites of antiquity and kept the encroaching sands swept and shoveled out, they were able to maintain their position of security. As soon, however, as the site was deserted, the sand would begin to drift over the deserted ruins. In a very few years the remains of the ruined city would be lost from the sight of men. Perhaps a century or two would pass by, during which this abandoned region would be devoid of habitation.

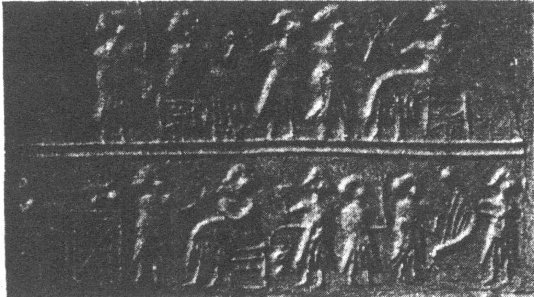

Plate 6

Mace-head in British Museum

Plate 7

Note cuneiform writing and sculpture on stone weapon

Then another company of people looking for a permanent dwelling place would chance upon this hill. Finding it suited to their requirements they would immediately start building upon the surface. With no knowledge whatever that a previous group of people had made this hill their habitation, the new dwellings and walls would rise high upon the covered ruins of the earlier period. Within a comparatively short time they also would be the victims of some wandering conqueror, and once again the wrecked habitations of men would be repossessed by the drifting sands of the desert. It is not uncommon that in the course of a thousand years such an experience would be repeated from three or four to a dozen times upon the same site.

When the archeologist finds such a mound or hill, he has a treasure indeed. By excavating this deposit one stratum at a time, he builds up a stratographical record which is highly important in reconstructing a consecutive history of this region. The date factors of the various strata are generally established by the contents of each horizon of dwelling, in turn. If the archeologist depends upon facts instead of his imagination, a credible chronology for the entire region can thus be constructed.

In such a recovery the common life of the people of antiquity is revealed in amazing detail. We learn their customs of living, something of their arts and crafts and their manner of labor. Their knowledge of architecture is clearly portrayed through such ruins as remain, and the general picture of the incidental events that made up their living is clearly developed as the work proceeds.

Since the destruction of such a city was usually catastrophic, the record suddenly breaks off at the point of the tragedy. The abruptness wherewith the life and activity ceased, leaves all of the valuable material undisturbed in situ. This circumstance, though unfortunate for the ancients, is a happy one for the archeologist who thus is enabled to rebuild their times and lives.

These sites yield many types of material. In establishing chronology, the most important of all of these is probably the pottery. There is no age of men so ancient that it does not yield proof of human ability in the ceramic art. Without aluminum cooking utensils or iron skillets, the folk of antiquity depended upon clay for the vessels of their habitation. Dishes, pots, jars, and utensils of a thousand usages were all made of this common substance. Before the invention of paper, clay was also the common material for preserving written records. As each race of people had its own peculiarities in the use of clay, the pottery that is found on a given site is one of the finest indications of a date factor that the site can contain.

Even after the invention of papyrus or parchment, these types of writing material were too costly for the average person to use. Requiring some cheap, common, readily accessible material upon which to write, the poor of antiquity laid hold upon the one source of supply that was never wanting. This consisted of shards of pottery. By the side of every dwelling in ancient times might be found a small heap of broken utensils of clay. The ingenuity of man suggested a method of writing on these fragments. In every home there was a pen made of a reed and a pot of homemade ink. With these crude tools, the common people corresponded and made notes on pieces of clay vessels. When a fragment of pottery was thus inscribed, it was called an ostracon.

These ostraca are among the most priceless discoveries of antiquity. They were written in the vernacular and dealt with the common daily affairs that made up the lives of the humble. They shed a flood of light upon the customs and beliefs of the mass of the people. Some of the wall inscriptions of great conquerors, if taken by themselves, would give an impression of grandeur and splendor to their entire era, if we believed such record implicitly. But for every king or conqueror there were multiplied thousands of poor. These were the folks who made up the mass of humanity and whose customs and lives paint the true picture of ancient times. Therefore, these ostraca, being derived from the common people, are the greatest aid in the reconstruction of the life and times wherewith the Bible deals.

Another source of evidence is found in tools and artifacts which show the culture of any given time and region. Knowing how the people worked and what they wrought, has been of priceless value to the Biblical archeologist. Since the critics made so great a case out of the alleged culture of the people in every age, it is eminently fitting that the refutation of their error should come from the people themselves.

Still another source of archeological material is to be found in the art of antiquity. It seems that from the time of Adam to the present hour the desire to express our feelings and emotions in the permanent form of illustration has been common to man. The sites of antiquity testify to this fact in unmistakable terms.

In the art of the days of long ago many subjects were covered. Much of the painting and sculpture had to do with the religion of the time. Thus we can reconstruct the Pantheon of Egypt very largely from the illustrations that come to us from monuments and papyri.

Another large section of ancient art dealt with the history of the time in which the artists lived and wrought. Since the work of such artists was generally intended to flatter and please the reigning monarch, most of this illustrated history is military in nature. Thus we are able to confirm much of the Old Testament history through the recovery of ancient art.

Other artists, in turn, dealt with the human anatomy, the style of dress and the industries of old. When we gather together all of this illuminating material, it is safe to say that ancient artists have brought to us a source of material which is not the least of the treasures of antiquity.

A final source of material is found upon the walls that made up the actual dwellings of old. This business of scribbling names and dates upon public buildings or objects of interest is not unique to modern men. Deplorable as the custom may be, this ancient vulgarity has, nevertheless, proved a great boon to the archeologist of our day. For instance, many of the scribes and officials of antiquity, traveling about the country upon the business of their lords, would visit one of the tombs of a former age. Prompted by curiosity and interest in the grandeur of antiquity, they came to stare and to learn. Their emotions being aroused they desired some expression. This desire they sometimes satisfied by inscribing upon the wall of a certain tomb or temple their names and the fact that at such a date they visited and saw this wonder. Since they generally dated their visit by the reign of the king under whom they lived and served, a chronology may be builded for antiquity from this source of material alone.

It has been more or less customary in our era for the itinerant gentry to leave valuable information for fellows of their fraternity who come along after them. This custom also is a survival of an ancient day. A man journeying from one region to another would stop by the side of a blank wall and inscribe road directions for any who might follow after him. Sometimes he would add his name and the year of the reign of a given monarch. It was not unusual also for such an amateur historian to make some caustic and pertinent comments upon the country, the officials, or the people. These spontaneous records are priceless. They are the free expression of an honest opinion and are not constructed with the idea of deluding posterity with a false standard of the grandeur of some conquering king.

It is rather amusing now to look back to the long battle that was fought between criticism and orthodoxy in this very field. With a dogmatic certainty which was characteristic of the assumptions of the school of higher criticism, these mistaken authorities assured us that the age of Moses was an age of illiteracy. In fact, the extreme scholars of this school asserted that writing was not invented until five hundred years after the age of Moses. We have ourselves debated that question with living men.

One such occasion occurred recently, when we were delivering a series of lectures at Grand Rapids, Michigan. The subject had to deal with archeology and the Bible, and the men in attendance seemed to appreciate the opening lecture extremely. Therefore, we were the more surprised when a gentleman, clad in clerical garb, came forward and in the most abrupt and disagreeable manner demanded,

“By what authority do you state that Moses wrote the Pentateuch? Your dogmatic assertion is utterly baseless!”

In some surprise we replied, “I am sorry to sound dogmatic, as I try never to dogmatize. All that I mean to imply is that I am absolutely certain that he did write it!”

Our humor, which was intended as oil on troubled waters, turned out to be more like gasoline on raging fires! The exasperated gentleman exclaimed with considerable more heat than he had previously manifested, “You can’t prove that Moses wrote the Pentateuch!”

“I don’t have to,” I replied, “as the boot is on the other foot! May I quote to you a section from Greenleaf on Evidence? Here is the citation: ‘When documents purporting to come from antiquity, and bearing upon their face no evident marks of forgery, are found in the proper repository, the law presumes such documents to be authentic and genuine, and the burden of proof to the contrary devolves upon the objector.’ Now, my dear brother, these documents do come from antiquity. They bear no evidence of forgery, and have thus been accepted and accredited in all of the ages that make up three millenniums of time. You face a problem if you are going to repudiate all the evidence and tradition of their credibility. Just how are you going to prove that Moses did not write these books ascribed to him?”

“That is easy,” the scholarly brother retorted. “Moses could not have written the first five books of the Bible, because writing was not invented until five hundred years after Moses died!”

In great amazement I asked him, “Is it possible that you never heard of the Tel el Armana tablets?”

He never had!

So we took time to tell him of the amazing discovery of this great deposit of written records from the library of Amenhetep the Third, and their bearing upon the great controversy. Then we told him also of the older records of Ur, that go all the way back to the days of the queen Shub Ab, and manifest a vast acquaintance with the art of writing as far back of Abraham as this patriarch in turn preceded the Lord Jesus Christ! He frankly confessed his total ignorance of this entire body of accumulated knowledge, and then closed the debate by stating,

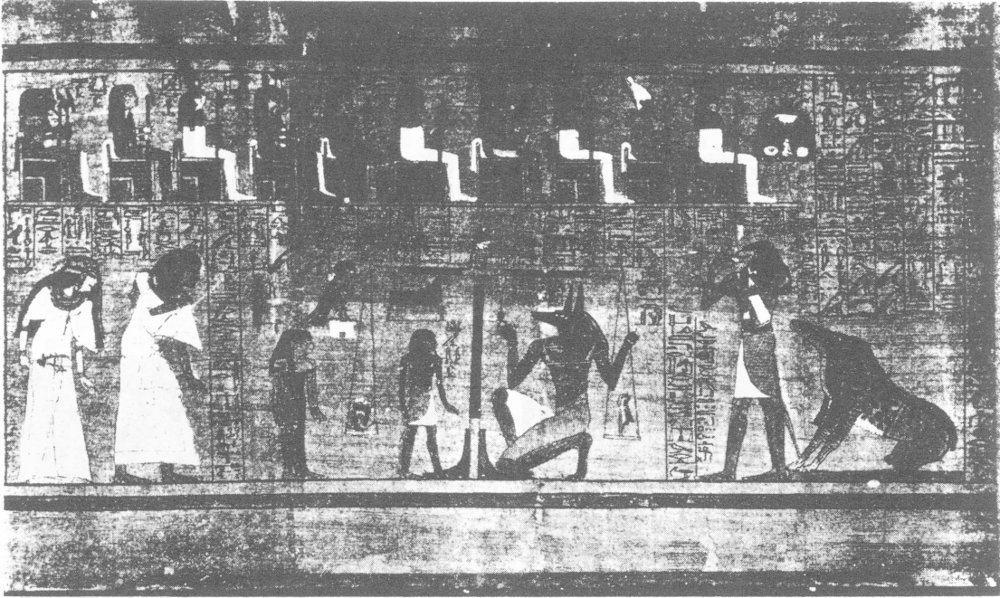

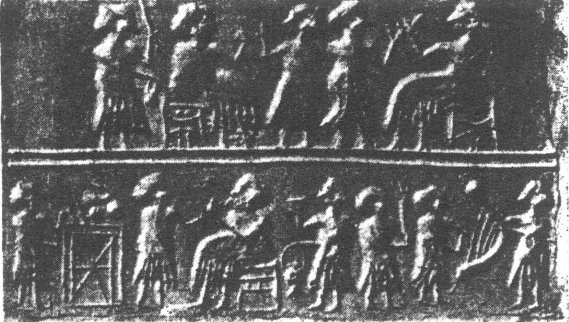

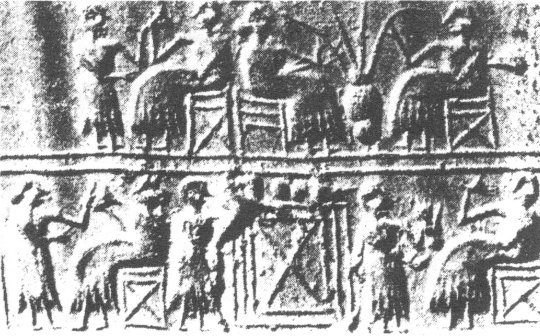

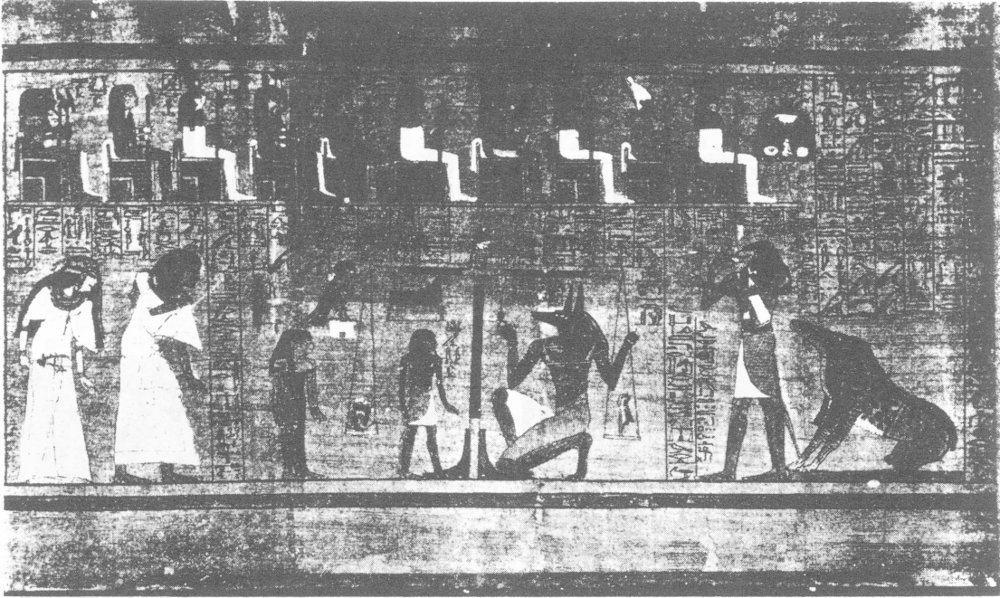

Plate 8

Ancient seals, depicting historic events.

Section of a funerary papyrus, showing the progress of the soul on its journey in the Other World

“Well, it may be that every one else in antiquity could write, but Moses couldn’t...!”

And such an one would accuse another of dogmatism! Because we stand upon the certainty of the approved and orthodox conception of the credibility of the Scriptures, and maintain our case with the most exact evidence, we are not “scholarly.” Yet here is a reputedly religious leader, utterly ignorant of an enormous body of knowledge derived from a generation of research, who misleads those who are unfortunate enough to be under his ministry, and offers them the fallacious, repudiated, and utterly baseless conclusions of higher criticism, in the place of the living bread which God has provided for His children! This is but to be expected when we think the matter through. The bread of life is to be found only in the pages of God’s Book. Therefore, if the source of this bread is rejected and derided, the bread cannot be available!

The great pity of the matter is seen in the fact that this attitude is entirely untenable, in the light of our present knowledge. Although our science has demonstrated a remarkable culture for the very age of the patriarchs, we are faced with religious leaders who are so far behind the advanced learning of our day that they still teach the outmoded nonsense of criticism, and claim that Moses could not write!

It is rather amusing in the light of this dogmatic assurance of critical authorities to journey back through the hallways of time and find that writing was a common custom a thousand years before Moses, or even a thousand years before that! Throughout Egypt especially, the art of writing was a universal possession among all classes of the populace. The toilet articles used by the beauties of Ancient Egypt were highly engraved with charms, and with prayers to the goddess of beauty. As an Egyptian damsel prepared herself for the evening’s engagement, she would read these prayers and charms which were supposed to give her divine aid in impressing the ladies with her outstanding beauty! Poems of love and lyrics of passion were engraved upon her toilet articles and were incised upon the walls of her apartment as well.

In addition to this, most of the ancients wore amulets to guard them against the evil eye and every sort of disaster.

Some wore engraved pectorals that showed the high development of the art of writing to a great antiquity.

Businessmen of various kinds, minor officials and even the common people carried upon their persons seals wherewith to sign the documents and contracts of their casual business affairs.

From this common source there is a kaleidoscopic view of ancient life that thrills the observer with its ever-changing magnitude. It is almost impossible to limit the value of such discoveries as to the integrity of the Scriptures. In all this enormous mass of authoritative data not one single fact has ever been derived which argued against the credibility of any statement in the Bible.

An even more important source of historical evidence is found among the papyri of old. This valuable material was invented in Egypt at a very early age. In Upper Egypt the Nile was bordered, and in some places overgrown, with a prolific reed which is scientifically called “cyperus papyrus.” It is from this name that the paper manufactured from this substance derives its identification. The manufacture of papyrus was a simple procedure which nevertheless required time. Briefly stated, strips of the papyrus reed, cut to a uniform length and saturated with water, were laid down side by side. Another layer of strips was laid across them transversely, and usually a third layer was superimposed upon the second layer. These layers of reed, being laid in alternate directions, were then pounded with a flat paddle and smashed into a pulp. When the mass dried, it was a sheet of rough paper, somewhat comparable to the paper towels that are used in our generation. The edges were trimmed smoothly and the surface of the paper was smoothed off with a shell or rubbed with sand. This finished side of the paper was called the obverse and was the side upon which writing was customarily inscribed. So expensive was this substance, however, that frequently both sides would be covered with writing. In that case the rough side was always known as the reverse. Many of these papyri not only were inscribed with a written text but were highly illustrated with scenes depicting the life and customs of the people. These illumined papyri, some of which go back to a very remote age, are of tremendous value to the student of the Scriptures.

We have, for instance, papyri from Egypt at the time of Moses, showing the fowlers engaged in capturing quail. (See Plate 10.) These birds being tired by their long flight in their annual African migration, fell easy victims to the men who smote them to the earth or captured them in hand nets. Incidentally, the author has frequently been offered such quail upon the streets of Cairo by vendors who earned a precarious living by peddling such game. Many Scriptural events are attested in this manner by these illustrated manuscripts.

Since there was a high content of starch in the finished papyrus, it was possible to make them any length desired. By moistening the edges of two sheets and pressing or pounding them together, the result would be a single sheet when the joint had dried. This process could be continued indefinitely. As a method of comparison let us note that the entire Gospel of John could be written on a papyrus of the usual width, if it was eighteen feet in length. Such a long sheet would be rolled to form a complete volume. The longest papyrus we have ever seen is in the British Museum and is exhibit No. 9999. This single sheet is 135 feet long.

Another papyrus of unusual length is that which shows the funery experiences of the scribe Ani. This is a highly illumined specimen and contains many illustrations of the soul of Ani, as he goes through the intricate process of achieving eternal life in the realm of Osiris. This papyrus is 78 feet long and is one foot, three inches wide. The average sheet of papyrus, however, is about six by nine inches.

These papyrus records are divided into many kinds and types. Some of them are funery, and deal with the events of the decease and resurrection of the individual. Most noteworthy among the papyri of this type are the various texts of the “Book of the Dead.” These are illuminated with scenes of religious beliefs. They depict the experience of the soul on its pilgrimage into the hereafter. They tell of the conditions of life in the other world and the manner of entering into a blessed state after death.

There are also papyri that deal with pure literature. Almost every subject common to modern literature is found in the ancient records of this type. For instance, fiction was a common field for the scribe of antiquity. The British Museum contains many of these prized papyri, as does the Egyptian Museum at Cairo.

It might surprise the modern reader to know that the Egyptian people of old highly prized stories of mystery and imagination. Some of their greater manuscripts bear a strong resemblance to portions of the Arabian Nights, and they may indeed have been the original basis of that later production.

In the British Museum a papyrus, No. 10183, is a fine example of this common theme. This is entitled, “The Tale of the Two Brothers.” In the introductory section, the life of a humble farmer in ancient Egypt is given in detail. The familiar triangle develops between the elder brother, his wife and the younger brother. The plot develops when the wicked wife made herself sick by rancid grease, and, bruising herself with a stick, lay moaning on the floor when her husband returned. Accusing the younger brother of attempted assault, she aroused her husband’s anger to the point where he grabbed an edged weapon and set out to kill the suspected villain. The oxen, however, told the younger brother of the ambush that was set for him and he fled the home. Marvelous miracles occurred during this flight, which opened the eyes of the elder brother to the injustice that he had been about to perpetrate. Whereupon he returned home, and satisfied the demands of the stern justice of his day by slaying his wife and feeding her body to his pet dogs. The rest of the story is taken up with the wanderings and adventures of the younger brother. This record goes back to the thirteenth century B. C., and is a perfect specimen of the fiction of that time.

Limited space will not permit the introduction of other notable classics of fiction such as the story of the shipwrecked sailor; the story of the doomed prince; the story of the possessed princess; the story of the eloquent peasant, and any number of other records, nor is their presentation essential to the development of our thesis. Their value, however, is seen in the fact that not only do they depict the literary tastes of antiquity, but they delineate many of the common details and incidents of the daily life of those ages.

There are also any number of poems which have a high historical value. We shall refer later to the famed poem of Pentauer, which immortalizes the victories of Ramses the Second, which this great conqueror achieved over Egypt’s ancient enemies the Hittites. The discovery of this record was the first appearance of the Hittites in archeology and caused a sensation in the ranks of Biblical criticism.

Among the more sober types of literature will be found narratives of pure history. Such would be the lists of the kings, giving the chronology of the dynasty of each. Records of conquest, lists of tribute, and the names of captive races form the bulk of this type of material.

There are also books of maxims teaching the higher morality of the age in which the papyrus was written. In a word, the literature preserved in the papyri of Egypt deals with religious aims, books of magic, records of travel, and the science of that day. From the latter we learn their beliefs and technique in the realm of astronomy. Their system of mathematics is preserved for us in such prize records as the Rhind Papyrus which deals with the geometry of that age. This papyrus is in the British Museum and is numbered 10,057. In the Museum at Cairo is a papyrus illustrating the geography and cartography of antiquity. This famous map shows the religious divisions of that province, which is now called the Fayyum. Others of these papyri deal with medicine as it was practiced in that ancient day. There are, of course, biographical papyri that are almost innumerable, all of which reconstruct for us the lives and times of these people who are so long dead, but far from forgotten.

Among the most important of all the varieties of papyri are those which preserve for us the embalming technique practiced at various stages in the development of this art in Egypt. Since the Egyptians believed that the resurrection of the body and its eternal life depended upon the preservation of the physical form, they took great pains in their preparations for the burial of their dead. The most graphic description of the method used is given by Herodotus and is thus familiar to all students of history. This noted writer states that three general methods were used by the Egyptians and the cost of each was graduated to the thoroughness of the method.

The most expensive means of embalming was an elaborate process indeed. The abdominal cavity was opened and the viscera were removed from the body. These were carefully washed in palm wine, thoroughly dried and sprinkled with certain aromatic spices. The brains were withdrawn from the head and treated in this same fashion. These cavities were then dried and filled with a combination of bitumen, myrrh, cassia and various other expensive and astringent spices. The openings were then sewed up. A tank was prepared which was filled with a solution of soda, and the body was steeped in it for seventy days. After removal from this pickling solution the body was thoroughly dried in the hot sun and anointed with spicy compounds which had the two-fold purpose of imparting a fragrant odor to the mummy and of further preserving its structure. The process was completed when the body was wound with the strips of linen with which all students of Egyptology are so familiar.

The cost of this type of embalming varied, of course, in each dynasty, but as a general average it would be in the neighborhood of $1500 in our modern currency. When we consider the disparity between our standard of money value and that of ancient Egypt, it can be seen that such a preparation was enormously expensive.

A cheaper method of embalming consisted of dissolving the viscera by means of oil of cedar. The flesh also was dissolved with a caustic soda solution, and the skin shrunk tightly to the bones. This dessicated form was then wrapped in the traditional linen bandages. The cost of this process was in the neighborhood of $300 in the currency of our day.

For the very poor, however, a cheaper form of preparation was used. The body was dumped into the tank of soda, where it was alternately saturated and dried for a period of seventy days. The pickled body was then handed over to the relatives, who wrapped it according to their own ability and means and arranged for burial at any convenient site. This process would cost in the neighborhood of $1.50 in our present standard of currency.

It will be noted that the customary period of embalming was seventy days. A discrepancy has been fancied here between this ordinary custom and the embalming of Israel, as it is recorded in the fiftieth chapter of Genesis. The third verse of that chapter states, “And forty days were fulfilled for him, for so are fulfilled the days of those which are embalmed: and the Egyptians mourned for him three score and ten days.” The discrepancy, however, has been cleared up by the discovery of the fact that under the Hyksos Dynasties the period of the embalming was forty days ins