CHAPTER VI

Fragments

“Rome was not built in a day,” is a self-evident truth: but it is equally true that it was not excavated in a day, either! In fact, as all visitors to Italy can testify, the Department of Antiquities is still working on some of the more ancient sites, and certain of the most extensive ruins are just beginning to emerge for the delight of our generation. Archeology is a very fine exposition of the truth inherent in the old proverb of science: “Research is the examination of the tenth decimal place.”

There are many stupendous monuments that have been uncovered with surprising speed, but the majority of our most valuable evidence has been derived from long and patient digging, and is often composed of innumerable fragments from here and there. Standing alone, any one of the many items that appear to be inconsequential would arouse no interest in the average observer, and would be passed over without comment. Such evidence is similar in its accumulative force to the action of water. A drop, or any number of single drops of water, attracts very little attention, but when enough of them combine to form a flood, great cities and whole nations sit up in alarm and pay strict attention to the course of the flow.

So it is today with the flood of facts that make up the great stream of discovery, and constitute so forceful a demonstration of the value and accuracy of the Bible. A few facts from Egypt suddenly fit into the pattern of certain other events that occurred in Assyria, and these in turn naturally correlate themselves with a record inscribed upon a stone by some king of Moab. Like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, these isolated and apparently unrelated facts make a complete picture when they are intelligently assembled, but careless or ignorant handling can never show the marvelous pattern in its complete beauty.

In this chapter we will offer a group of these fragments from here and there, and show their value to the student who seeks evidence on the question of the authority of the Holy Word. Their accumulated force is irresistible, and their final authority cannot be refuted. Just as grains of sand make up a mighty mound when they are assembled into one great heap or deposit, these fragmentary facts have an imposing authority when they are taken together. In support of this statement, we shall cite the problem of chronology.

One of the greatest difficulties that has always faced the students of antiquity was the construction of an accurate and detailed chronology. The early Egyptians paid no attention whatever to chronological sequence, but dated the episodes and events which they recorded by the year of the contemporary monarch. Among the Chaldeans and the Sumerians, however, lists of eponyms were carefully kept. In the Assyrian meaning of this word an eponym was an official whose name was used in a chronological system to designate a certain year of office. From these consecutive records of the eponyms, king-lists of unusual and detailed accuracy were compiled. A great deal of the difficulty in harmonizing the chronological factors in the study of antiquity has recently been solved by a close study of these canons, which studies were first begun by Sir Henry Rawlinson. As an instance, we note that one such consecutive list gives all of the eponyms from B. C. 893 to 666.

Another magnificent aid to the Biblical chronologist is found in the astronomical data which were so carefully kept at the same historical period. Through these credible records we have the material to check the accuracy of the king-lists that adds to their tremendous value. For instance, a tablet has come to us stating that in the eponym of one Pur-sagali, there was an eclipse of the sun which took place in the month Sivan. Since Sivan would be composed, according to our calendar, of the last two weeks of May and the first two weeks of June, it is easy to make an astronomical calculation to fix this date. We are delighted to find that there was an eclipse of the sun which would have been visible at Nineveh on June 15, 763 B. C. With this factor fixed, we can now date all of the events of that period of antiquity from these king-lists to the time of the beginning of the reign of Assur-bani-pal.

Another such tablet, which came from Babylon, gives us an opportunity to check back the other way. This tablet merely states, “In the seventh year of the reign of Cambyses, between the 16th and 17th of the month Phemenoth, at one hour before midnight, the moon was obscured in the vicinity of Babylon by one-half of her diameter on the north.” We then turn to our modern astronomical sources and learn from them that there was just such an eclipse of the moon which would have been visible in Babylon in the year 522 B. C. Since this was the seventh year of Cambyses, it follows that he must have ascended in the year 529.

This is exactly what is demanded by the Biblical chronology accepted at our present time. Incidentally, by correlating the prophecies and history of the Old Testament to the proved chronological points in these records, archeology has vindicated the historical and traditional acceptance of those dates which criticism unsuccessfully disputed. The kings of Israel and Judah, with the writing prophets of each monarch’s reign, may now be correlated into this accredited system of chronology. When this is done, the traditional and accepted dates for the prophecies of the Old Testament which orthodox scholarship has always maintained, are established beyond reasonable doubt.

In the confused condition of the Egyptian chronology it is difficult to dogmatize concerning the exact identification of certain pharaohs whose records are contained in the Sacred Text, but who are not identified by their prenomen in Holy Writ.

A good deal of this confusion, however, is being dissipated with surprising rapidity due to the recovery of some hitherto unknown sources. The tendency of our present day is to concede that the Pharaoh Thotmes, whose name is more commonly given as Tuthmosis, was the pharaoh of the Oppression. There is a great deal of reliable authority for adopting this view. This mighty sovereign, whose history we have partly covered in connection with his sister, wife and domineering queen, Hatshepsut, in the portion dealing with the times of Moses, according to the best chronologist, reigned fifty-one years. He died in 1447 B. C., and was succeeded by Amenhetep the Second. This fact would make it practically certain that the latter monarch was the pharaoh of the Exodus.

There is a great deal of gratifying demonstration in the new chronology which, being purged from the gross errors that naturally resulted from chronological differences inevitable to pioneers in Egyptology, has brought great comfort and aid to the orthodox believer in the Old Testament. There were almost as many different dates given by the critics for the Exodus from Egypt as there were critics. It may be noted in passing that one of the major difficulties of criticism and one of its foundational weaknesses is to be seen in the fact that each individual critic is his own highest authority. The only finality that criticism recognizes is the dogmatic decision of a particular individual to believe one way or the other.

So it is rather hard to say that criticism in general held to any certain thing. The consensus of opinion, as far as such can be gathered from criticism, however, would make the date of the Exodus not any earlier than 1220 B. C.

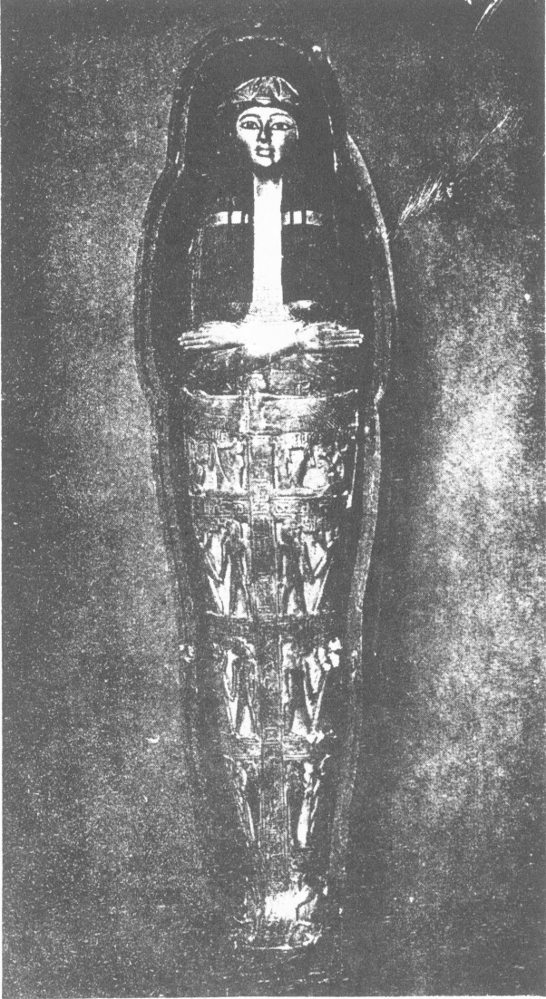

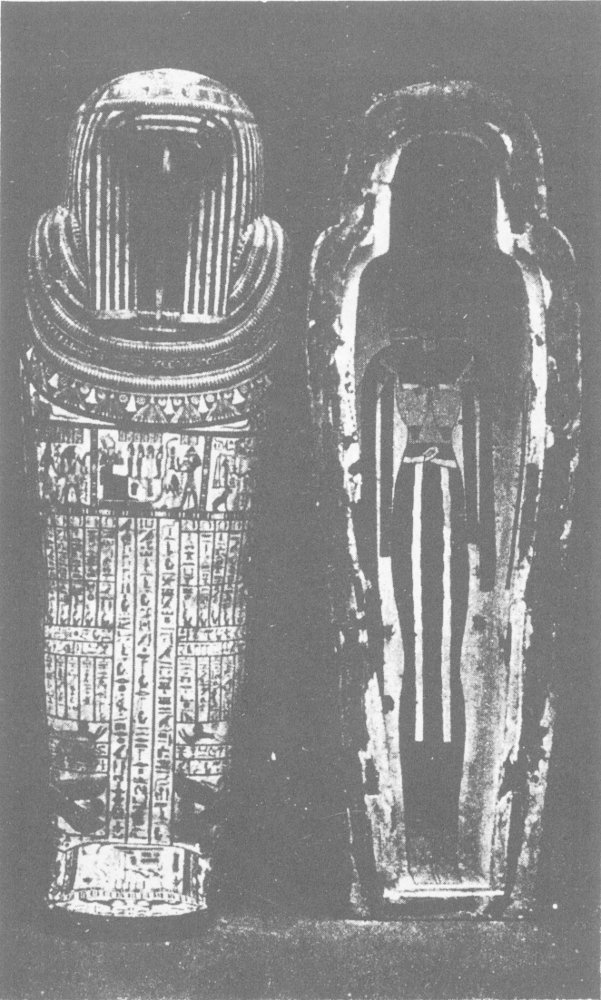

Plate 11

Cartonnage in the anthropoid sarcophagus

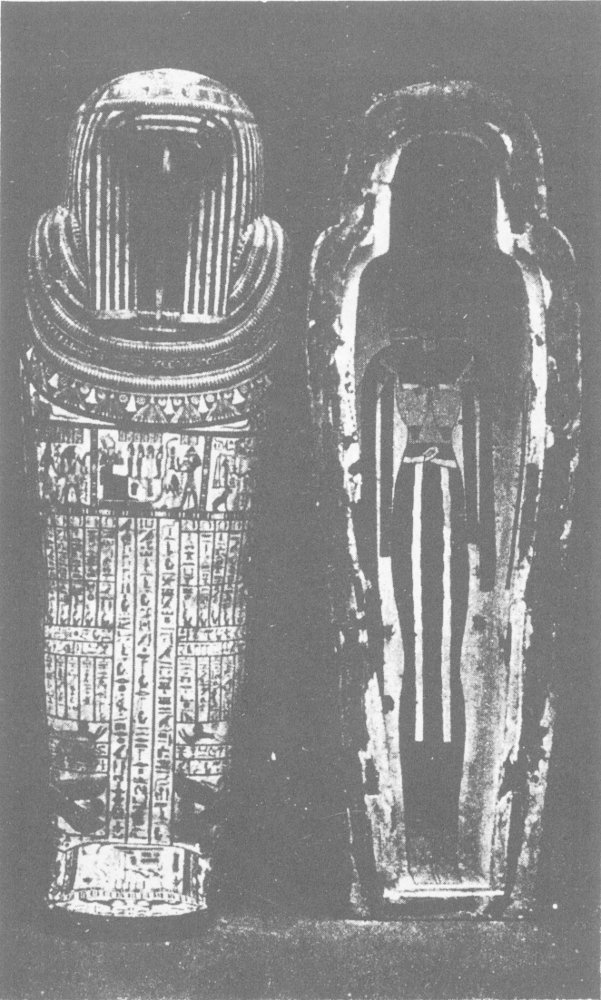

Plate 12

Showing both outside and inside writings and decorations on anthropoid sarcophagus

The new chronology, derived from archeological research, has utterly and finally upset these critical conclusions. The Exodus can be credibly dated now to within a span of ten years. The earlier probability is 1447 B. C. and the latest possible time would be 1437. It may be said that if we consider the archeological sources alone, there is a possible spread of thirty years, but no more. Even if we make the most liberal concessions, the Exodus must be fitted into the record between 1447 and 1417 B. C. Allowing then for the years of wandering in the wilderness, the fall of Jericho occurred with a possible spread of ten years, between 1407 and 1397. The earlier date is now accepted as by far the most credible. We may state almost with finality that Jericho was destroyed in 1407 B. C., and remain secure in that conclusion.

Therefore, if Tuthmosis died in 1447, the reign of Amenhetep the Second would have ended in 1421. These perplexing seals of Amenhetep, if they have not been derived by intrusion, would thus have had a sufficient time to reach Jericho in connection with some official business of the kingdom in the forty years elapsing between the Exodus and the assault on the Canaanite city.

It will be remembered that Josephus makes a passing reference to the statement of the Egyptian historian, Manetho, that the pharaoh of the Exodus was Amenophis. Amenophis is another form of the name Amenhetep, which would add a great deal of authority to our present conclusions. Josephus is not willing to acknowledge the dependability of Manetho, due to the fact that Manetho came so long after the event. But since the Egyptian historian preceded Josephus by some three hundred years, the older authority would seem to be at least as dependable as Josephus! Incidentally, this fact, if accepted, would be a confirmation of the accepted date for the Tel-el-amarna tablets with the reign of Amenhetep.

The final word as to the date, based upon authoritative evidence derived from the pottery culture as given by Dr. Garstang, makes the destruction of Jericho to have been not later than 1400 B. C. Thus the pendulum of opinion and discussion has now swung back to the point where we can authoritatively stand upon the earlier conclusions of the Book of Joshua and accept its credibility without the slightest question.

Most of us can remember how recently it was the fashion for the opponents of the Bible to laugh at those who believed in the historicity of Joshua’s strange conquest of the Canaanite city of Jericho. The collapse of the walls of that ancient city has long been a source of mystery to the scientific student, and of hilarity to the unbeliever. The faith of the intelligent is vindicated, however, and the laughter of the unbeliever is stilled, by the exhaustive work that archeology has done in the vicinity of Jericho.

The site has been explored a number of times, but the most comprehensive and conclusive work was done by the 1933 expedition that was headed by Dr. Garstang. The walls of Jericho were mighty, and as long as they stood the city was impregnable to the armed forces of antiquity. The unusual structure of Jericho’s walls was manifested when they were uncovered from the dirt and debris of centuries. The word “walls” is properly given in its plural form as there were outer and inner walls that entirely encircled the city. There was, first of all, surrounding the city completely, an outer wall, which seemed to have been held up as much by faith as by gravity!

Ever since we had the first opportunity of personally examining the geology of Jericho and noting the insecure structure upon which those walls were builded, our own private wonder has not been that the walls fell down; rather we have been bewildered by speculating as to what in the name of physics ever held them up! Perhaps it was the binding of the buildings that anchored the outer wall to the inner wall, and made a sort of tripod structure of the whole, which accounted for this phenomenon. Some fourteen feet back from the outer wall and roughly paralleling the convolutions of the former, there was an inner wall of the same height as the outer one. Across these two walls great beams had been laid, and dwellings constructed upon this unique foundation. The outer wall was pierced by the one gate, in exact accordance with the description in the Book of Joshua.

There is no natural explanation to account for the unique evidence of the collapse of these walls. They were not undermined by military engineers, for they all seem to have collapsed around the entire circumference of the city at one and the same time. They were not shaken down by an earthquake. This would have resulted in a haphazard piling of the wall material in a number of different directions. It seems as though a mighty blast had been set off in the center of the city, thrusting the walls outward, in what might roughly be described as a circle. This collapse of the walls naturally resulted in the wrecking of the houses builded thereon. When the preliminary clearance had been made and the excavators came down to these great ruins, every demand of the Book of Joshua was satisfactorily met by the conditions there uncovered.

In the remnants of the houses found in Jericho there was overwhelming evidence of a systematic destruction by fires that were set to sweep the entire ruin. Among the most interesting and significant of the charred evidences were the great stores of burned grain which showed that even the food of Jericho had been dedicated to the fire, as Joshua had commanded.

When the discoveries of Jericho were first publicized, Dr. Garstang could find only one apparent contradiction between the record of Joshua and the evidences in the city. That was in the time factor, or chronology, that was involved. In the cemetery of Jericho upon its excavation, there were found two seals of the Pharaoh Amenhetep the Third. Since this monarch reigned probably at least a hundred years after the time of Joshua, it was difficult to reconcile the apparent discrepancy. The apparent difficulty, however, dissolves when we consider the possibility of later intrusion.

Before the excavations at Jericho could begin, it was necessary for the workers to clear away the remains of a fortress of Ramses, the monarch who headed the nineteenth dynasty, which in turn followed that of the dynasty of Amenhetep the Third. Since this site had been temporarily used by the Egyptians two hundred years after its destruction, it is highly probable that it might also have been temporarily visited by them the century immediately following its destruction. If the presence of two seals of Amenhetep are to be taken as a date factor in view of the fact that burials at that site were by intrusion, then a great case could be made for a later date by the ruined fortress of Ramses.

The pharaoh who ruled in the day when Joshua led the conquest of Canaan was most probably Tuthmosis the Third, who reigned contemporarily with the Queen Hatshepsut until he was sufficiently entrenched to overthrow her dominion. This queen, as all the evidence most clearly suggests, was most probably the one who drew Moses out of the Nile. The contemporary and collateral evidence is fairly conclusive, so that this fact is generally accepted. Relegating the one anomalous discovery, then, to the probability of intrusion, we find that Jericho, perhaps more than any other site in antiquity, has vindicated the record of the Old Testament text.

In this very connection, it is interesting to note how the queen Hatshepsut came into the record, and first interested the student of apologetics. The eminent archeologist, Flinders Petrie, found a tablet on the slope of Mt. Sinai which was written in an archaic script that baffled every attempt to decipher its mystery for nearly thirty years. But at long last Professor Hubert Grimme, who held the chair of Semitic languages at the University of Munster, made out two words. One of these was the ancient Hebrew name for God, which in this form of writing appeared as “JAHUA.” The other word that Dr. Grimme succeeded in reading was “HATSHEPSUT,” who was known from her monuments and obelisk.

With this key, the table was quickly deciphered, and was ascribed to Moses. The text as it appeared follows:

“I am the son of Hatshepsut

overseer of the mine workers of sin

chief of the temple of Mana Jahua of Sinai

thou oh Hatshepsut

wast kind to me and drew me out

of the waters of the Nile

hast placed me in the temple (or palace).”

On the reverse were directions for locating the place where the writer reported he had buried certain tablets of stone, which he had broken in his anger. Since all the landmarks the writer used to identify the place of burial have disappeared, nothing has so far come from the search that resulted when this tablet was at last read.

Incidentally, this queen Hatshepsut left her mark upon the age in which she lived, as she was one of the most persistently determined women who ever appeared upon the pages of ancient history. There is a remarkably complete record of her history and her imperial reign which may be read today in the relics of her times and in the ruins of the great works which she caused to be constructed.

Her important place illustrates one of the difficulties of chronology, which we have previously mentioned. Her background is clear and undisputed. When Tuthmosis the First died, his son and heir Tuthmosis the Second succeeded to the throne. He was a physical and mental weakling, and very little is known of him from the monuments of old. But he married his half-sister Hatshepsut, and started a train of events that had surprising consequences. Incidentally, it was the custom for Egyptians to marry in the closest family ties, and brother and sister more often wed than not. In view of this famous lady’s character and later conduct, it is highly probable that the king had no choice in marrying his sister, but was led to the slaughter whether he would or not! At any rate, he died very soon after the wedding, and the widow Hatshepsut declared herself queen. To make her position secure, she married her young stepson and half-brother, Tuthmosis the Third, who was the legal and rightful heir to the throne. During his boyhood the queen reigned in undisputed power, and developed the country in a surprising manner.

She was a feminist with a vengeance, and called herself KING Hatshepsut, and stated that she was a god and as such was entitled to worship and obedience. What is more, she made it stick! Since she could not lead her armies in person, she pursued the ways of peace, and the troubled land had rest and prospered. Some of the greatest building operations of the ancient world were begun and finished under her direction and patronage.

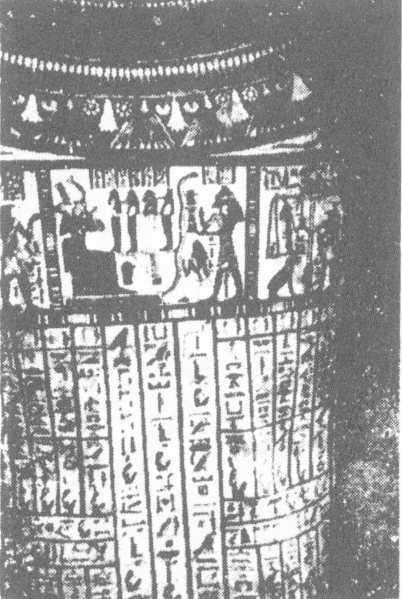

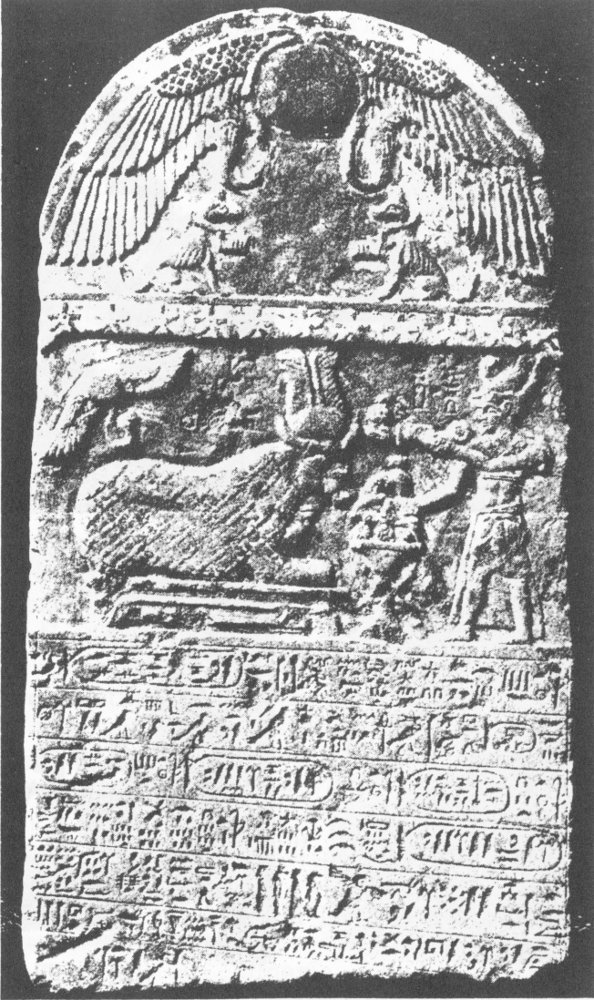

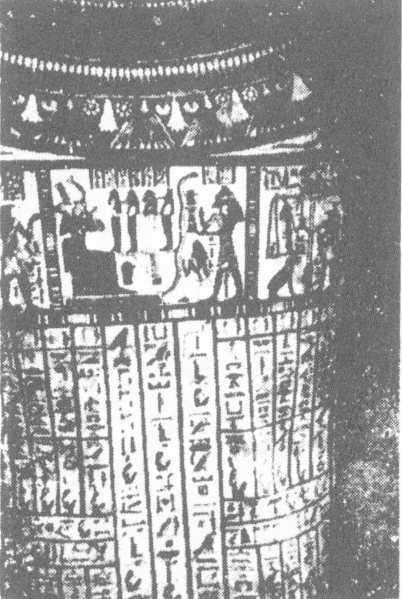

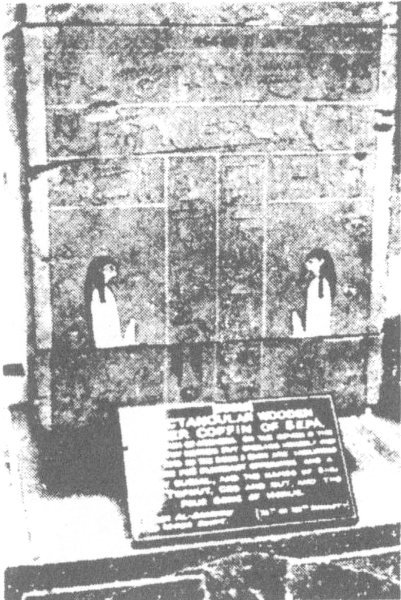

Plate 13

Detailed study of outside and inside of anthropoid coffin. Note voluminous record

Outside, or rectangular coffin also covered with writing and records

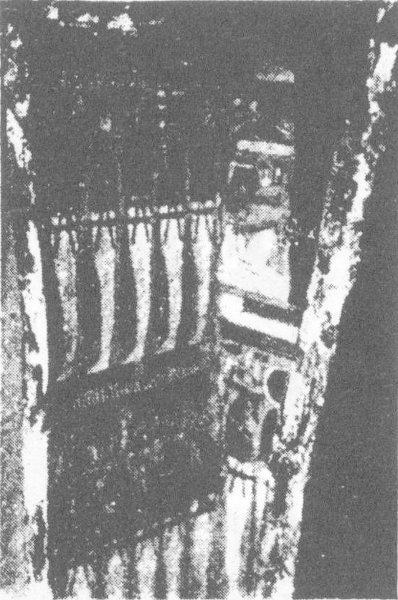

Plate 14

Murals and frescoes from tomb walls

When her husband-brother-consort became of age, he naturally rebelled against her usurpation. He gathered a company of adventurous nobles about him and forced the queen to abdicate, after which she disappeared under circumstances which would have interested Scotland Yard, if that noted institution had been in existence in that day and place! The ambitious young king took the name of Tuthmosis the Third, and left a brilliant record as a conqueror and builder. Counting the twenty-one years he lived as co-regent with Hatshepsut, he ruled the land fifty-three years, which was an enviable span for those warlike days.

If the present accepted chronology is right, he came to the throne in 1501 B. C. and died in the year 1447. This would have made him the Pharaoh of the Oppression! In which case, the queen Hatshepsut would have unconsciously offended him in elevating Moses to a place of prominence and power, which might explain why Moses felt it necessary to flee from Egypt when he was in trouble. At any rate, out of this tangled skein of human conduct and ambition, some present help is offered to the learning of our day by the known facts that have been clearly established from the relics of this embattled couple. The name of the queen Hatshepsut was abhorrent to her brother-husband-regent-successor; and he tried to obliterate it wherever it appeared. But she had built so many great works and had left such ample records that his actions in this matter came to nought, and she lives today to shed the assurance of probability upon the record of Moses.

We have seen her obelisks, her records and some of the ruins of her great works, and the entire pattern is of a piece with the demands, both chronological and ethnological, of the text of the Scripture. It is apparent that not only dead men, but also dead women, may tell tales, if their voices are heeded and the ears of the listener are not stopped with the wax of infidelity and disbelief.

The amazing and scrupulous accuracy which is maintained by the Old Testament in its historical statements is once again demonstrated by the record of Ahaz as it is given in the Old Testament and found on the monuments in Assyria. We read in II Kings and the sixteenth chapter, these words:

In the seventeenth year of Pekah the son of Remaliah, Ahaz the son of Jotham king of Judah began to reign.

Twenty years old was Ahaz when he began to reign, and reigned sixteen years in Jerusalem, and did not that which was right in the sight of the Lord his God, like David his father.

But he walked in the way of the kings of Israel, yea, and made his son to pass through the fire, according to the abominations of the heathen, whom the Lord cast out from before the children of Israel.

And he sacrificed and burnt incense in the high places, and on the hills, and under every green tree.

Then Rezin king of Syria, and Pekah son of Remaliah king of Israel, came up to Jerusalem to war: and they besieged Ahaz, but could not overcome him.

At that time Rezin king of Syria recovered Elath to Syria, and dwelt there unto this day.

So Ahaz sent messengers to Tiglath-pileser king of Assyria saying, I am thy servant and thy son: come up, and save me out of the hand of the king of Syria, and out of the hand of the king of Israel, which rise up against me.

And Ahaz took the silver and gold that was found in the house of the Lord, and in the treasures of the king’s house, and sent it for a present to the king of Assyria.

And the king of Assyria hearkened unto him: for the king of Assyria went up against Damascus, and took it, and carried the people of it captive to Kir, and slew Rezin.

The visit of Ahaz which closes this record was made in 732 B. C. Tiglath-pileser has left his own story of these stirring events and has called Ahaz by name upon his monument. The unfortunate action of Ahaz in calling for Assyrian aid against his enemies Pekah king of Israel and Rezin king of Syria, resulted, according to Tiglath-pileser’s account, in his invasion of both Syria and Palestine. From thence he carried away into captivity the two tribes of Reuben and Gath, and the half tribe of Manasseh. The distress of Israel was not ended until Hoshea, shortly afterward, became the new king of Israel. As a matter of policy he formally accepted the yoke of Assyria and became the vassal of Tiglath-pileser.

In the Assyrian Room of the British Museum, Wall Cases 14 to 18 contain a valuable collection of inscribed bowls, ostraca, and fragments of records which extend from the days of Assur-resh-shi, down to the end of the Assyrian dynasty. Among them are fragmentary inscriptions from the reign of Tiglath-pileser the Third. He is known in the Scriptures also by his Babylonian name of Pul. In I Chronicles 5:26 both names are found in the one verse, as though the scribe were anxious that the identification should be complete:

And the God of Israel stirred up the spirit of Pul king of Assyria, and the spirit of Tiglath-pileser king of Assyria, and he carried them away, even the Reubenites and the Gadites, and the half tribe of Manasseh, and brought them unto Halah, and Habor, and Hara, and to the river Gozan, unto this day.

Tiglath-pileser again appears under the name of Pul in II Kings 15:19:

And Pul the king of Assyria came against the land: and Menahem gave Pul a thousand talents of silver, that his hand might be with him to confirm the kingdom in his hand.

In the twenty-ninth verse of this chapter, however, his Assyrian name is given alone, as is done in the sixteenth chapter.

In the above cited wall cases, exhibit K 2751, is an inscription of Tiglath-pileser’s setting forth some of his conquests, and an account of certain of his building operations. Among the tributary kings who accepted his yoke, he specifically mentions Ahaz king of Judah.

Modern man is so used to the phenomena that make up the miracle of our modern living that such fascinating possessions as this are not generally appreciated and properly valued. Here, however, we hear again the voice of a man who died in the year 727 B. C. The phenomenon is seen in the fact that in spite of the indescribable vandalism and wreckage wrought by those intervening ages, a fragment of clay persisted, and remained in existence until it could be uncovered from the dust heaps of antiquity by the one generation that desperately needed its testimony and was able to interpret and prize its record!

Here indeed is a dead man who tells tales, and who tells them with such authority and accuracy that the mouth of criticism is stopped and the Word of God completely vindicated. Incidentally, Tiglath-pileser’s record corroborates the prophecy of Isaiah, concerning the destruction of both Israel and Syria, because they had joined their forces to make war upon Judah.

This prophecy is given at length in the seventh chapter of Isaiah and was the instance of introducing the greater prophecy of the final redemption of the people with the coming of Messiah. He was to be identified, according to Isaiah, by means of the miracle of the virgin birth.

When Omri, the general of the armies of Israel, was elevated by popular acclaim to the throne of dominion, he climaxed an astonishing career that left a deep impression upon antiquity. At the beginning of his reign the nation was divided in its allegiance and this division resulted in a civil war that was bitter, though brief. The power and might of Omri quickly pacified and subdued the land, which accepted his dominion, and for twelve years his hand guided the helm of the ship of state. One of his earlier acts was to buy the hill of Samaria for a sum that is given as two talents of silver, which would be in the neighborhood of $4,000 in our reckoning. So impressive was his personality that from his day on to the end of the kingdom, the land of Israel was generally known among the Assyrian peoples as the Land of Omri.

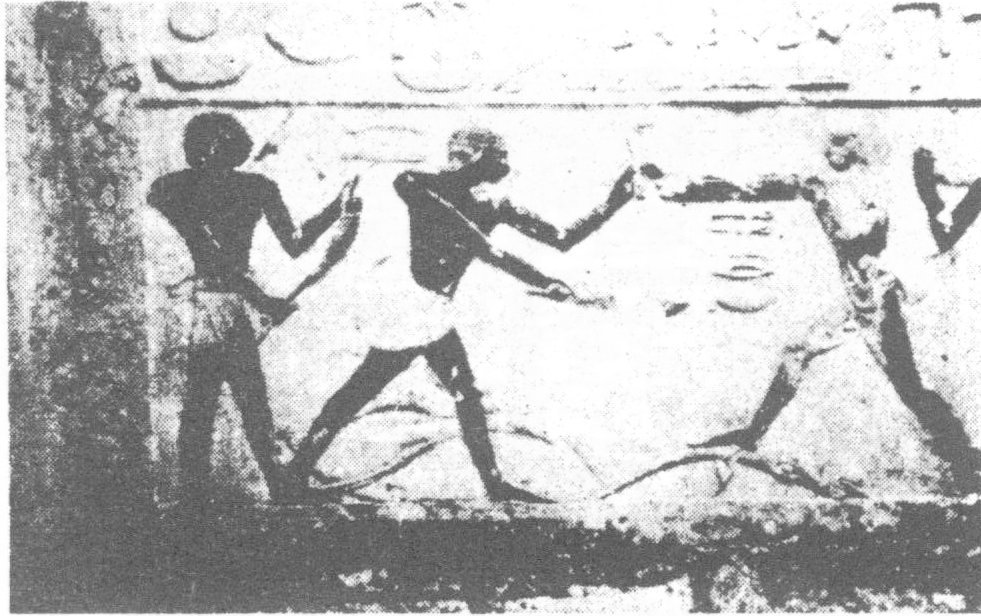

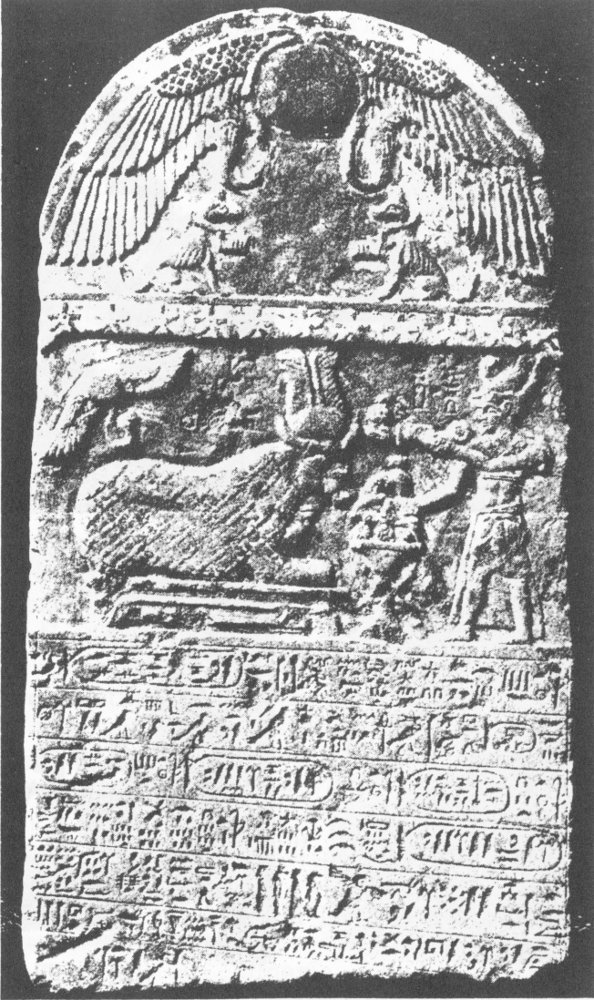

On the black monolith for instance, which was set up by Shalmaneser the king of Assyria, there are many sculptured pictures which illustrate the text of this priceless historical record. One of the scenes shows that among the conquered rulers, one is entitled “Jehu the son of Omri.” A record is made of the silver, gold, lead, vessels of gold, and of other materials that Jehu brought in tribute to Shalmaneser. (See Plate 18.) This black obelisk may be seen in the Nimrud Central Saloon of the British Museum in London. That this was a general is seen from the fact that on the nine-sided prism which gives the record of Sargon concerning his conquests in Palestine, the great Assyrian lists the people of Israel whom he calls “Bit-Khu-um-ri-a” (Omri-land), among other subdued races. Omri was succeeded on the throne by Ahab, who was a young man when he came to the throne. He left an unenviable record of apostasy and idolatry, but was none-the-less a courageous and able administrator whose work strengthened the realm greatly. In the twenty-two years of his reign the Word of God was ignored and unbelief swept over the land. In his day the first persecution of God’s people, which was directed against their ministry, began when his wife Jezebel caused the slaughter of the prophets.

The entire career of Ahab occupies considerable space in the records of the Old Testament and is almost as prominent in the monuments of antiquity. One of the most outstanding and notable of his early acts was the famous overthrow of Benhadad, the king of Syria. The invasions of Israel by Benhadad are fully covered in the historical texts of the Old Testament, so they need no recapitulation here. When the Syrian king suffered an overwhelming and crushing defeat at the hands of Ahab, he submitted himself to the king of Israel with a humble plea for mercy. In spite of the denunciation of the prophet, who warned that Benhadad would bring disaster upon the realm, Ahab restored him to his Syrian dominion and made a covenant of brotherhood with him. Later on, Ahab and Benhadad united in a rebellion against their Assyrian overlord in one of the most disastrous acts of his career. The battle that decided the campaign was fought at Karkar.

In the British Museum, the Nimrud Central Saloon exhibits a stele of Shalmaneser the Third which bears the identifying number of 88. The inscription sets forth the names, titles, and ancestry of the king and gives a complete account of several of his military adventures. He states that in the sixth year of his reign, he battled against certain allies who had rebelled against his authority. Among them he lists “Ahab of the land of Israel.” Shalmaneser tells how he defeated this coalition and slew fourteen thousand of the Syrian warriors in one great battle.

Plate 15

Commem