CHAPTER VII

The Rebirth of an Empire

Among the ancient races that are catalogued in the lists which appear in the pages of the Old Testament, the most important one in the presentation of this thesis is the Hittite race. In the heyday of their brief popularity the higher critics indulged in an orgy of refutation concerning these sections of the Scripture. Since the Hittites are mentioned forty-eight times in the pages of the Bible, if it could be proved that these people were fictitious in character, the critical case against the Old Testament would be demonstrated beyond question. It would almost seem as though the writers of the ancient word had invited this contest with deliberate intention. It is impossible to justify the manifold appearances of the Hittites in the Sacred Word, if they were not an actual people.

In addition to the many other references, in the various lists of races given as occupying different portions of the ancient world, the Bible mentions the Hittite peoples twenty-one separate and distinct times. The eminent dean of higher criticism, the late Canon Driver, ascribes these historical catalogs of peoples to imagination and fiction, and refers to them in such words as these, “The Hittites are also regularly mentioned in the rhetorical lists.” Canon Driver is careful to note that these lists of peoples are found in that section of the Scripture which he calls the “Elohistic Manuscript.” It is not hard to understand that one who starts with the assumption of incredibility, would have trouble believing in the reality of the statements in a document so treated.

The writers of the Scripture, in their dealings with the subject of this forgotten people, sketch an amazing picture indeed. They portray a warlike, powerful, well organized race whose genius at colonization and military ability combined to win for them a veritable world empire. The center of their dominion was Syria, but from thence they reached out to lay their yoke upon Egypt, to overrun Palestine, and to force the early Assyrians to pay tribute to their might and power.

It seems almost inconceivable that in the voluminous records of antiquity there should have been no single word concerning this mighty race. For until the closing decades of the nineteenth century, the Hittites had no place in secular history. They were preserved to the memory of man, simply and only because of the forty-eight Old Testament references which we have previously mentioned. The scholarly critics argued that it would be impossible for a world empire to disappear from history without leaving a single trace. They insisted that if a race of men had ever lived who dominated the world of their day, common sense would incline us to the conclusion that they could not suddenly fade away from the memory of man and leave no evidence of their existence.

But they did! From the very beginning of this argument, it should have been apparent that there were two ways to approach the problem. One way was the method which was adopted by the higher critics, namely, to assume that the Old Testament is fallible. Adopting as the grounds of investigation the pre-conceived conclusion that the records of the Old Testament are fallacious and incredible, the critics then proceeded to search for proof of this basic assumption. By dogmatically asserting that the Old Testament was not historical, but that much of its contents consisted of folklore and myth, inductive conclusions were offered as proof of this presumption.

It did not seem to occur to the higher critical scholars that a better way to study the Word would have been to concede the historicity of the text until it was disproved by evidence. This, of course, has ever been the method used by the orthodox student of the Word. We might say in passing that this is not only the intelligent technique but is also the safer process. To say the very least, it saves the embarrassment that inevitably comes to him who arrays himself against the integrity of the Word of God!

The first appearance of the Hittites in the Bible is in the fifteenth chapter of the Book of Genesis, verse twenty:

“And the Hittites, and the Perizzites, and the Rephaims.”

This is perhaps the very earliest coincidence of archeology with the records of the Scripture. In the various lists of races who were to be displaced by Israel, according to the covenant God made with Abraham, the Hittites are frequently named. Without any reservation or qualification whatever, this text which we have just cited states that the Hittites were Canaanites. According to Genesis 10:15, the Canaanitish people came through the line of Sidon and Heth. It is apparent also from Genesis 10:6, where Canaan the son of Ham first comes into the record, that these Hittites, if they had existed, would have been akin to the early population of Chaldea and Babylon. It is an interesting fact to note that the monuments of antiquity which have restored these Hittites to their proper place in secular history, show them to have had a mixture of Semitic and Mongolian characteristics.

In the various appearances of these people in the Old Testament records, it is to be noted that several characters married Hittite wives. Bathsheba, who was the mother of Solomon, and thus infused a Gentile strain into the genealogy of Mary, who was the mother of our Lord, was a Hittite woman. In I Kings 11:1, it is also stated that Solomon, among his many political marriages, had taken to himself wives from among the Hittites.

These people, although unknown in the orderly annals of human history, might have been recognized had the scholarly ability of earlier generations been able correctly to interpret obsolete systems of writings. The Assyrians called them the “Khatti.” In the Egyptian inscriptions they are known as the “Kheta.” The fact that these names referred to the Hittites was not known until the Hittite inscriptions themselves were read and interpreted and the fact of their reality established. It is to be regretted that in a work as short as this one we have not room to recapitulate their long and fascinating history. The romance of their recovery of their rightful place in the annals of human conduct is all that we can present in this chapter. They were thrust by human ignorance into the outer darkness of forgotten things, but we can trace the hand of God in bringing them back into the light of remembrance and establishing them in their proper place of glory and prominence among the empires of antiquity.

Without hesitation we would offer this as the perfect demonstration of the manner in which Almighty God cares for His Word. When His Book is assailed and discredited, He will, if need be, raise the dead to establish the integrity of the Inspired Record. It might be noted in passing that secular history is now often corrected by archeology. The misunderstandings and errors which were alleged to appear in the Bible, and which are common to the production of a purely human document, are being done away with as we read them again in the light of the monuments. Wherever such correction has been made, it has had the effect of bringing secular history into complete harmony with the Bible. So in restoring the empire of the Hittites to the staid columns of accredited history, the Divine Record is again confirmed.

It is inevitable that these Hittites should appear in the Ancient Word, as they largely parallel the history of the Hebrew kingdom in point of time. From the days of Abraham to the end of the kingdom of Israel, the Hittites and the Hebrews walked side by side and hand in hand. During that time Hittites and Israelites alike are the enemies of Egypt. Alike they battled against Babylon and Assyria, they intermarried, had treaties and covenants each with the other, and had a well developed system of commerce between the nations.

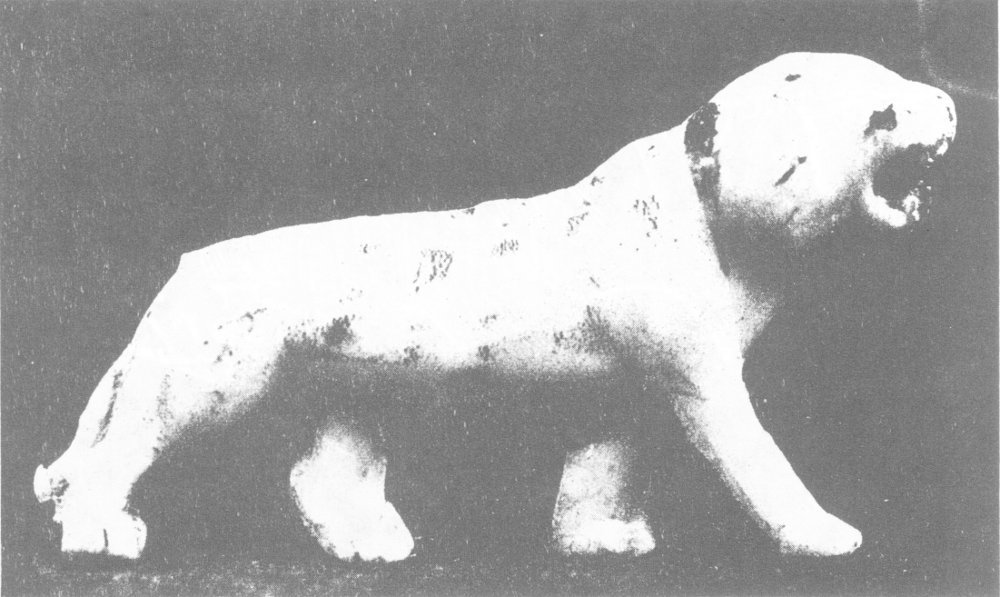

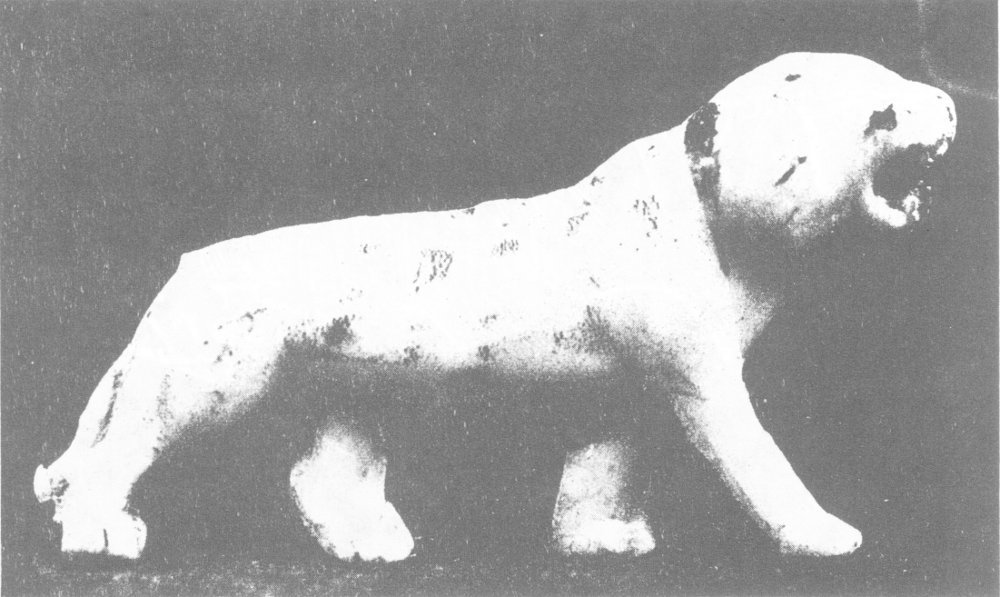

Plate 19

Small ivory lion from Ahab’s palace

Author’s collection (Photo by Dworshak)

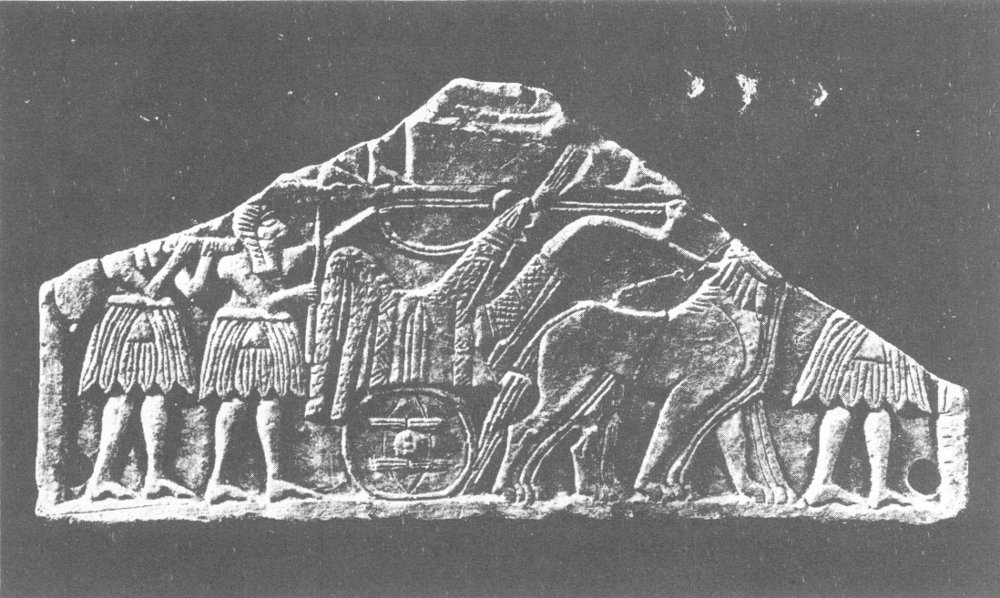

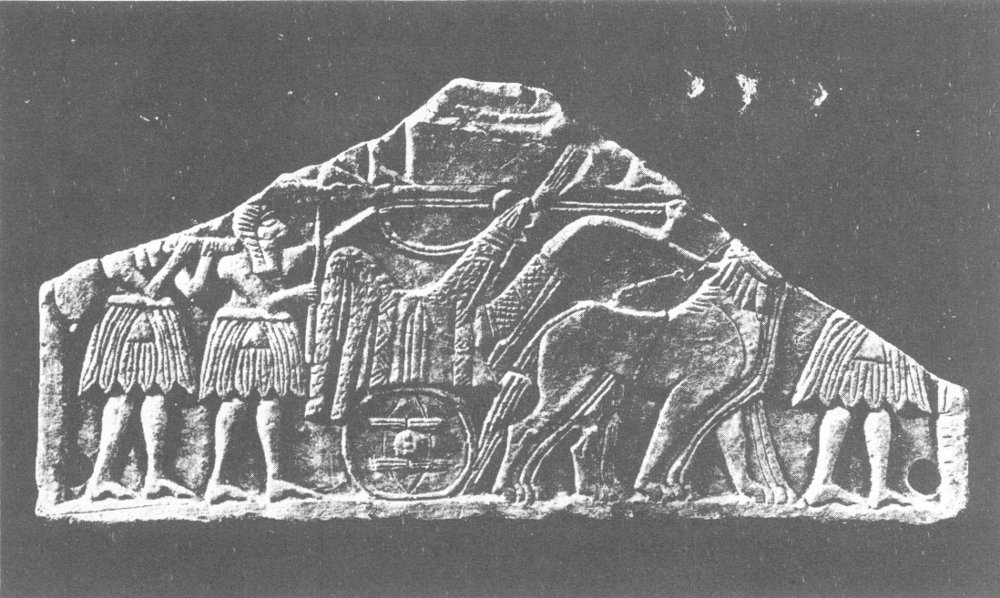

Plate 20

Fragmentary frieze showing ancient chariots (Museum of the University of Pennsylvania)

King Solomon, the merchant prince, had developed business relations with all of the many chieftains and kings of the Hittite peoples, and had a well developed trade in the horses and chariots for which the Hittites were famous in their day. (See Plate 20.) This coincidence of affairs began when Abraham consummated the first commercial transaction that is mentioned in human history. Before Abraham left Ur of the Chaldees to begin his strange pilgrimage, the Hittites were already established in Canaan. It must not be thought that Abraham at that time was the ancient prototype of our modern hobo, wandering from point to point with no estate! The pastoral pursuits of Abraham had built up for him flocks and herds that made him enormously wealthy. He was an able strategist, and his military skill, combined with his personal valor, had elevated him to a high position of power and influence.

In the land of Canaan he was treated with honor and admiration as befitted his station and position. His armed retainers constituted a formidable army for that day, and this trained manpower compelled respect for Abraham, the wandering prince. When Sarah died, the Hittites were in possession of the land and Abraham recognized the validity of their title when he opened the negotiations for a burial plot for Sarah, by defining himself as a stranger and a sojourner in their land. With typical oriental courtesy in bargaining, the Hittites replied to his request for a burying place for his dead wife by saying, “Hear us, my lord, thou art a mighty prince among us,” and they offered him freely and without price the choice of a plot for a sepulchre. Abraham designated the cave of Machpelah as his choice and offered to pay the full value of the site. This courtesy, of course, was expected of him. Though it had been offered as a free gift, it would have been a breach of manners of the worst type, according to the customs of that day, for him to have accepted the gift.

It will be noted in this account in Genesis that when Abraham weighed out the requested price of four hundred shekels of silver, the statement was made that it was the shekel which was the current money with the merchants. The sum was equivalent to about $300 in our present system of values. This is the first reference made to coinage, and it fits in beautifully with the archeological indications that the Hittites were the inventors of the principle of coining both gold and silver as a medium of exchange.

From this first moment of their contact with Abraham there is no period of Hebrew history, up to the time of the fall of Samaria, where the people of Israel lost contact with the nation of the Hittites. Their mercenary soldiers became captains in the army of David and Solomon, and they were occasionally allied in important battles in which the people of Israel fought side by side with them. It is amazing that the critics, in the face of the tremendous emphasis laid upon the Hittite empire by the writers of the Scripture, did not exercise some discretion in their repudiation of the historicity of this people. Even while the tongues of the unbelieving were clamoring with loud denunciations of the text of the Word of God, Libya, Syria, and Asia Minor in general exhibited magnificent sculpture, incised stones, and monuments written in a strange system of hieroglyphics that none had been able to read. These proved later to be the records of the Hittite peoples as they themselves had cut them with their own hands.

We shall later refer to the great work of Dr. A. H. Sayce in deciphering these hieroglyphics. His achievement in that instance was, in the annals of human history, one of the greatest triumphs of pure reason. Before this was done, however, the Hittites had begun to stretch themselves and stir in the tomb of oblivion. Their long sleep was ended and they began to rise from the dead, when experts in Egyptology read the record of Ramses the Second. It is not too much to say that these early discoveries threw the camp of higher criticism into utter confusion.

Ramses the Second successfully ended a period of warfare with the Hittites which had vexed and distressed Egypt for more than five hundred years. So great was the power of the Hittite empire that no previous conqueror or king in Egypt had been able to shake off their yoke completely. Indeed, Ramses the Second succeeded in so doing only by contracting an important political marriage with a Hittite princess.

The center of the Hittite empire was Charchemish. On the site of Megiddo, which was so often the scene of battles in successive years, the forces of Ramses fought with the armed forces of the Hittites. There the Egyptian monarch successfully defeated the Hittites in one of the most stirring battles preserved to us in ancient records. The Hittites at this time were governed by a number of kings who had a close confederation in all affairs pertaining to the empire. In the day of Ramses the confederation was headed by the king of Kadesh. According to Ramses’ record, which is preserved for us on the walls of Karnak, all “the kings and peoples from the water of Egypt to the river-land of Mesopotamia obeyed this chief.”

This army of the confederation massed itself on the bloody field of Megiddo in a battle which lasted six hours. Ramses tells in detail how he marched and maneuvered his forces to gain strategic advantages.

It was a coincidence that the battle began on the morning of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the ascension of Ramses the Second. He celebrated the anniversary of his crowning by throwing off the yoke of the Hittites. A complete victory was denied Ramses, due to the fact that when the Hittite force broke and fled before him, his army failed to take advantage of the rout. Falling upon the rich plunder, they fought among themselves over the spoils so long that the Hittites were able to enter their fortified city and barricade it against the Egyptians. An element of humor enters into the final statement. Ramses recounts that he besieged the city for a number of days, but since “Megiddo had the might of a thousand cities, the king graciously pardoned the foreign princes.” In the list of the spoil that the Egyptians gathered from this battle, there occurred the names of one hundred nineteen towns and cities which henceforth paid tribute to Egypt. The next important item was the capture of nine hundred twenty-four chariots, including the personal chariot of the Hittite king which was plated and armored with gold. (See Plate 20.)

Although Ramses boasted that he had “completely overthrown the might and power of the Hittites,” the future history of this Pharaoh depicts campaign after campaign lasting until the end of his life. At least nine campaigns are recorded on the walls of Karnak, in each of which the Hittites were singularly exterminated, completely overthrown, and defeated for all time hereafter. The only trouble seems to have been that the Hittites didn’t realize how completely they were defeated, so that they came back again and again! The nearest to peace that Ramses ever achieved, in his dealings with this race, was when upon his marriage with a Hittite princess, a great treaty was signed. In the records of his battles, Ramses refers to the Hittite king as “the miserable lord of the despised Hittites.” When he records the treaty that he made at the time of his marriage, he refers to the same man as “his noble and magnificent brother, a fellow to sit with the god of the sun by the side of Ramses himself.” It is evident, then, that some of Ramses’ records must be taken with a grain of salt. We noticed recently, as we were studying and photographing the battle scene of Megiddo which is portrayed on the north side of the great temple at Karnak, that Ramses is shown as having thrown to the ground all the Hittites and as having slain their king. Seven years later, however, the king is still alive to give his daughter in marriage to Ramses!

Since the Hittites were at this time the central power of the ancient world, peace with them meant peace with all the other enemies of Egypt. Perhaps, for this reason, Ramses’ boasting of his great victory might be pardoned.

This great battle is also immortalized by a contemporary poet. The papyrus copy of this poem is now in the possession of the British Museum. Many stanzas from this notable work, however, are to be seen in connection with the magnificent battle pictures at Karnak. Some of these are also repeated in the temple at Luxor, as well as on the great monument at Abydos.

Professor Wright refers to this poem as “the earliest specimen of special war correspondence.” This work is known as the poem of Pentauer. Pentauer is the name of a Theban poet who wrote his dramatic ode two years after the battle between Ramses the Second and the Hittite horde. The boastful extravagance of his language becomes a bit wearisome as he sings the praises of Ramses and chants of the impossible feats of the monarch. An example of hyperbole is offered in this verse:

“King Pharaoh was young and bold. His arms were strong, his heart courageous. He seized his weapons, and a hundred thousand sunk before his glance. He armed his people and his chariots. As he marched towards the land of the Hittites, the whole earth trembled. His warriors passed by the path of the desert, and went along the roads of the north.”

The “miserable and deceitful king of the Hittites,” however, had prepared an ambush. When the Hittites sprang their trap with their king in their midst, Pharaoh called on his mighty men to follow him. Leaping into his chariot, he assaulted the numberless horsemen and the armored footmen of the horde of the Hittites, and plunged into the midst of their ablest and bravest warriors. As he fought his way into the press of these noble horses, Ramses looked around to see how his force was getting along. To his surprise he found that they had not followed him; and he was hemmed in by two thousand five hundred chariots which were manned by the mightiest of the Hittite champions. Deserted by his entire army, Pharaoh saw that he had to rely upon his own ability, so “shouting for joy, with the aid of the god Amon, he hurled darts with his right hand and thrust with the sword in his left hand!” He “slew two thousand five hundred horses which were dashed to pieces!” He “laid dead the noble Hittite knights until their limbs dissolved with fear and they had no courage to thrust!” He swept them into the river Orontes and slew as long as it was his pleasure.

It is quite evident that Pentauer relied largely upon his imagination for the details of this great battle. However exaggerated this poem may be, nevertheless it has some historical value. Especially is this so since the poem of Pentauer and the Karnak record of Ramses the Second are in virtual agreement as to the essential details of this battle.

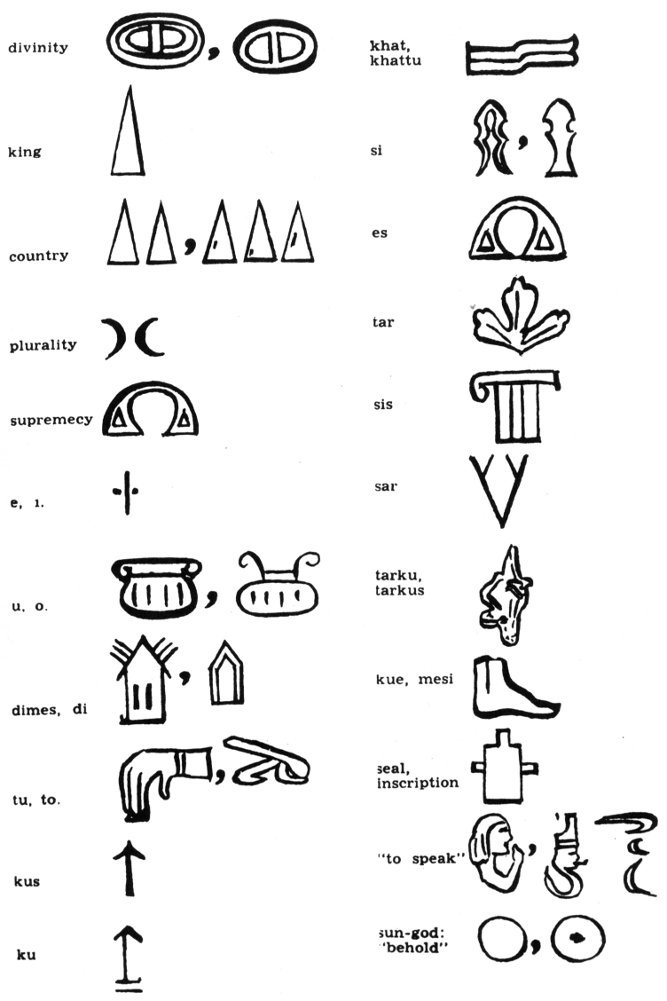

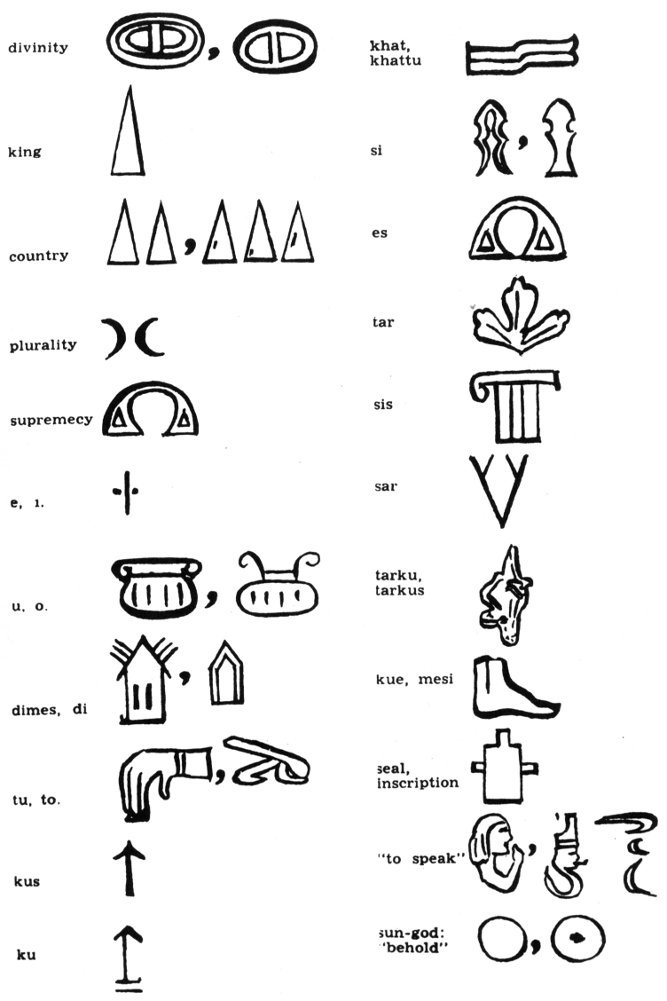

Plate 21

{hieroglyphs}

divinity

king

country

plurality

supremacy

e, i.

u, o.

dimes, di

tu, to

kus

ku

khat, khattu

si

es

tar

sis

sar

tarku, tarkus

kue, mesi

seal, inscription

“to speak”

sun-god: “behold”

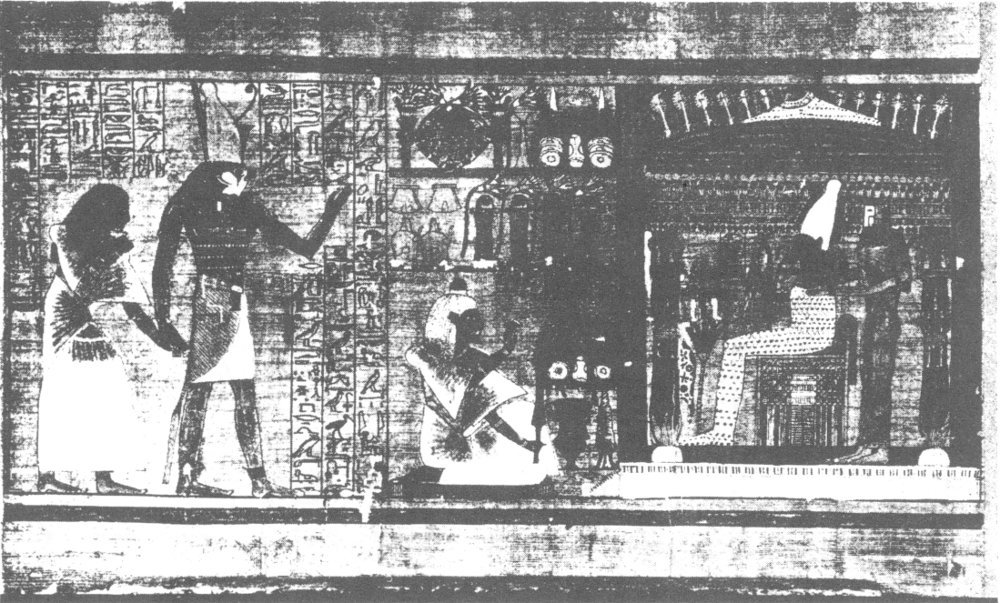

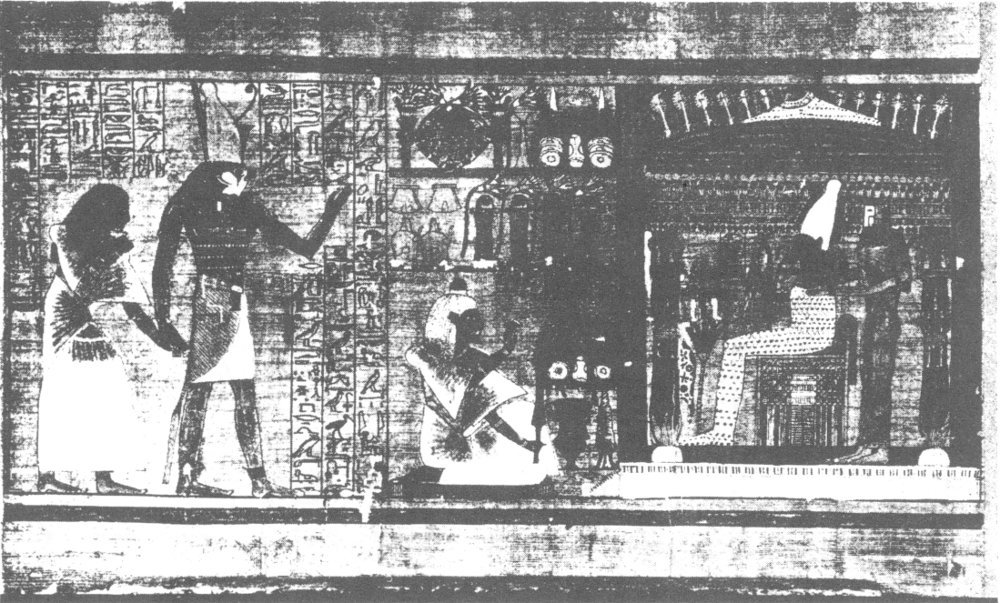

From such funerary papyri much valuable information regarding Egyptian beliefs and customs is derived

Incidentally, the walls of Karnak yielded from the records of other kings the historic evidence of an actual Hittite empire. Tuthmosis the Third immortalized the Hittites on the walls of Karnak when he gave a list of towns in the land of the Hittites over which he was victorious. Unquestionably this list contains the first and oldest authentic account of ancient cities, which are frequently afterwards mentioned in the Assyrian records as well. This record is found in the splendid temple which is called the “Hall of Pillars” and which was erected by this notable pharaoh. It has been said that in this work the art of Egypt reached its highest point. Certainly the walls and pillars are literally covered with the beautifully engraved pictures and names of the races and cities which the pharaoh had conquered.

When the Department of Antiquities was working upon the wall of a lower section, a catalog of one hundred nineteen conquered places came to light. This record showed that, more than three hundred years before the Israelites entered the land of Canaan, the Hittites were established in a powerful dominion over that lovely land. There are seven separate records of the contacts of this pharaoh with the people who were the Hittites.

Ramses the First has also left a record of the treaty of peace that he made with the Hittite king Seplal at the end of the war that he unsuccessfully fought to throw off the yoke of this people. On the north wall of the temple at Karnak, he gives the route of his march and tells of the victories that he won. He did not, however, delineate his final capitulation. This conflict resulted in a treaty of peace which is recorded in this account.

The successor of Ramses the First was Seti the First, and in his day the treaty was broken. According to Seti, it was the Hittites who offended against the covenant, and he also engraved on the walls at Karnak an account of the consequent battle with its result. To bring just a short line from his voluminous record, he acknowledges his own greatness in such an inscription as the following:

“Seti has struck down the Asiatics; he has thrown to the ground the Kheta. He has slain their princes.”

Telling them how he concluded a treaty with the Hittites, to the enhancement of his own glory, Seti’s record concludes with these words:

“He returns home in triumph. He has annihilated the people. He has struck to the ground the Kheta. He has made an end of his adversaries. The enmity of all people is turned into friendship.”

With just this brief reference to the voluminous records to be found in Egyptian archeology, we would be able to establish the triumph of the Bible in the realm of historical accuracy, had we no other sources. The fact of the matter, however, is that the Assyrian and Babylonian accounts of the Hittites are at least as numerous as are the Egyptian.

It may be noted in passing that, although filled with consternation at these marvelous discoveries in Egyptology, the critics were by no means silenced. It would have been better for their later reputation had they graciously accepted their defeat and acknowledged that they were in error. Instead, they rushed into vociferous refutation of the newly discovered Egyptian records. Unfortunately, their denunciations and renewed claims were given wide publicity by being included in the then current edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. It is to be regretted that this great encyclopedia has often been a tremendous aid to criticism in spreading its errors and fallacies. This in large measure is due to the fact that there is a common reverence for this great work in the mind of the average human. There is a certain class of readers who hold this notable reference work in such great reverence that its authority to them is greater than that of the Word of God. It must be remembered, however, that the encyclopedia of each generation represents only the current thought of that brief period of human experience. Anything that is written by man is subject to later revision or repudiation, as human knowledge increases. So in this great compendium of human wisdom it is unfortunate that much space was given to the famed critic, the Rev. T. K. Cheyne.

This eminent authority was a Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. In the above cited article, he treated the statements of the Bible as unhistorical and classified them as pure folklore. Concerning the Biblical references to the Hittites, he used these exact words, “They cannot be taken as of equal authority with the Egyptian and Assyrian inscriptions!” In dealing with Abraham’s purchase of the burial plot for Sarah, he had a great deal to say in refutation of the possibility of any accuracy in the record. At the conclusion of his criticism he stated, “How meager the tradition respecting the Hittites was in the time of the great Elohistic narrator, is shown by the picture of Hittite life in this reference.”

Dr. Cheyne fell into the great error of claiming that the Hittites were only warriors. Because they are thus shown on the walls of Karnak, he concluded that they were mercenary troops who never entered into business transactions. In his article on the Canaanites in this above cited encyclopedia, he goes so far as to say, “The Hittites seem to have been included among the Canaanites by mistake. Historical evidence proves convincingly that they dwelt beyond the borders of Canaan.” These conclusions were also advocated by his great colleague and collaborator, Prof. W. H. Newman.

Dr. Newman was also a Fellow of Balliol College at Oxford and is the author of the once famous “History of the Hebrew Monarchy.” In all of this work he maintained that the Hittite references in the Old Testament were unqualifiedly unhistorical. They prove beyond question, according to the author, that the writers of the Old Testament were totally unacquainted with the times of which they wrote. His conclusion was that the Old Testament was written many centuries after the events which it purports to depict. He stated with finality, along with Dr. Cheyne, that the Hittite people were limited to Syria and had no place in Palestine. Thus the story of Abraham buying territory from them at Hebron is unquestionably mythological.

These ardent advocates of a collapsing theory should have waited! It was not long after these utterances were printed that Prof. Sayce deciphered certain of the Assyrian records of Tiglath-pileser. These showed that in the reign of this monarch, as late as 1130 B. C., the Hittites were still in command of all the territory from the Euphrates to Lebanon!

Again the Word of God was vindicated, when the monuments, as they were deciphered, yielded the interesting information that the Hittites were notable colonizers. They also covered all the ancient world as merchants, and their caravans and trade-routes were the earliest to be established. They are in Assyrian annals depicted as artisans and artists. Although all of them could fight when war was inevitable, they had a standing army for the casual and necessary protection of the realm. Dr. Newman was unfortunate also in choosing the time in which he charged the Bible with error. At a most unfortunate period for criticism in the history of archeology he questioned the details of Hittite prowess in the incidental references of the Scripture. As though the scientists of that day were in league with the Lord, they laid bare in site after site a refutation of all the critics maintained!

It will be remembered that in connection with the siege of Samaria, as the story is given in II Kings, the seventh chapter, there is a peculiar but important reference to the Hittites and their known power. The people of Israel who were commanded by Jehoram were distressed by the siege of their capital when Benhadad of Damascus had pressed them to the limit of their resistance. Famine and disease had swept Samaria, so that the remnant faced the choice of surrendering or perishing. Elisha had prophesied a deliverance, and in verses six and seven in the seventh chapter of II Kings, the fulfillment of God’s promise is given in this way:

“For the Lord had made the host of the Syrians to hear a noise of chariots, and a noise of horses, even the noise of a great host: and they said one to another, Lo, the king of Israel hath hired against us the kings of the Hittites, and the kings of the Egyptians, to come upon us.

“Wherefore, they arose and fled in the twilight, and left their tents, and their horses, and their asses, even the camp as it was, and fled for their life.”

Professor Newman found a great deal of grounds for hilarity in what he called this “childish narrative.” He says, “The unhistorical tone is too manifest to allow of our easy belief in it.” He admits that there may have been some unusual deliverance of Samaria, because of collateral records of dangerous night panics among various hordes of antiquity. He adds, however, in reference to the Bible account, “The particular ground of alarm attributed to them does not exhibit the writer’s acquaintance with the times in a very favorable light. No Hittite kings can have compared in power with the king of Judah, the real and near ally, who is not named at all. Nor is there a single mark of acquaintance with the facts of contemporaneous history.”

Two sources of information, however, have since been derived that flatly refute the learned Professor and vindicate the accuracy of the record of God’s Word. The Assyrian sources show conclusively, upon the examination of their records, that the Hittites at that time were the greatest power with which the monarchs of Chaldea had to deal. In the records of Assur-Nasir-pal a long and powerful tribute is paid to the military might of the Hittites. So in that day they were still a strong and warlike people. They were especially dreaded by the armies of antiquity because of the unique distinction of their chariots. It is to this fact that the writer of II Kings refers when he speaks of “the noise of chariots.”

The walls of Karnak give us a clear and illuminating description of these ancient weapons of battle. Each chariot was drawn by two horses, armored and shod with spikes. Three warriors rode in each chariot. One of these handled the reins, while the other two plied arrow, javelin, sword, and dart, working untold havoc in the closely packed ranks of ancient infantry. (See Plate 20.)

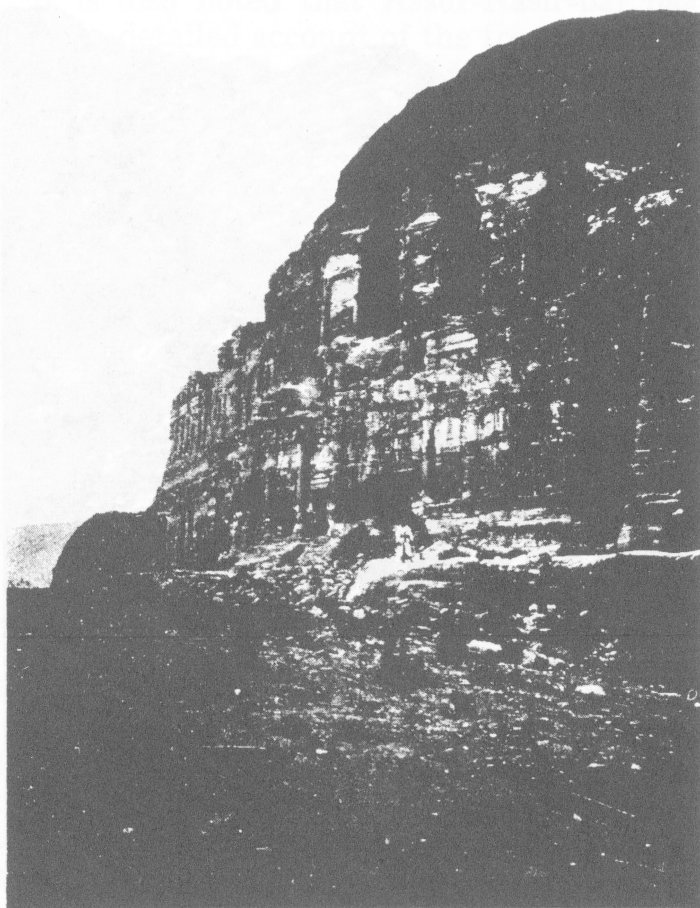

Plate 22

Monuments of Petra, showing extent of the ruins in one direction

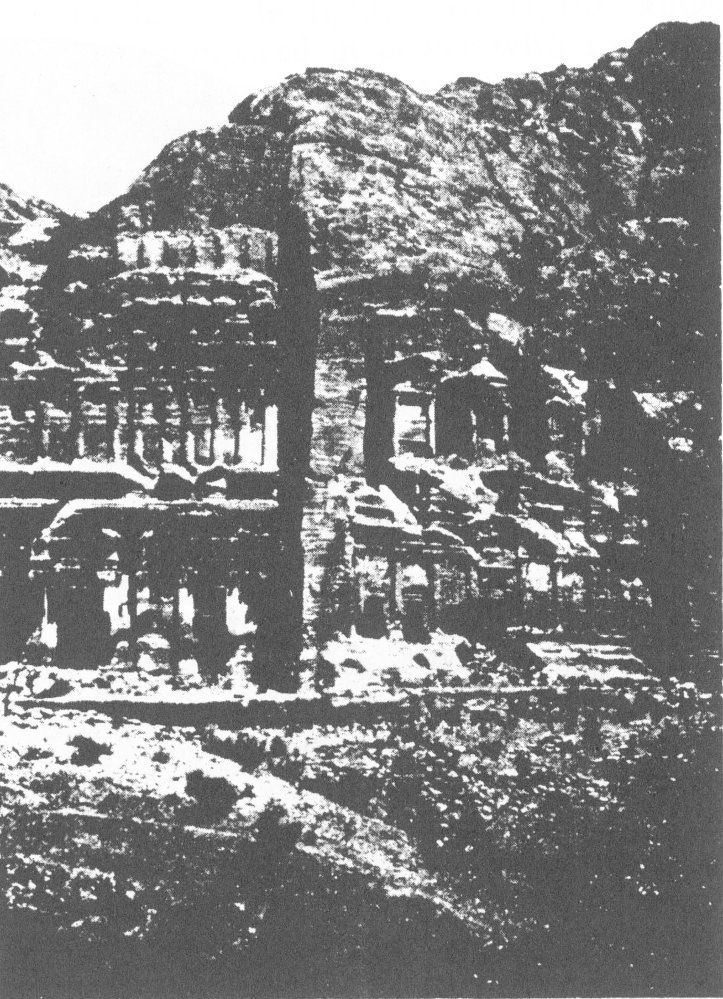

Plate 23

L