APPENDICES

APPENDIX I.—ON S. PETRONILLA

Baronius, followed by Bishop Lightfoot of Durham and others, calls attention to an etymological difficulty which exists in attempting to derive Petronilla from Petros, which at first sight seems so obvious. These scholars prefer to connect the name “Petronilla” not with Petros but with “Petronius.” Now, the founder of the Flavian family was T. Flavius Petro. Lightfoot then proceeds to suggest that “Petronilla” was a scion of the Flavian house, and became a convert to Christianity, probably in the days of Antoninus Pius, and was subsequently buried with other Christian members of the great Flavian house in the Domitilla Cemetery.

De Rossi, however, and other recent scholars in the lore of the Catacombs, in spite of the presumed etymological difficulty, decline to give up the original “Petrine” tradition, but prefer to assume that Petronilla was a daughter, but only a spiritual daughter, of the great apostle—that is, she was simply an ordinary convert of S. Peter’s.

Of these two hypotheses: (a) dealing with the first, in the very free and rough way in which the Latin tongue was treated at a comparatively early date in the story of the Empire, when grammar, spelling, and prosody were very frequently more or less disregarded save in highly cultured circles, the etymological difficulty referred to by Lightfoot can scarcely be pressed, for it possesses little weight.

(b) As regards the second hypothesis—the shrinking, which more modern Roman Catholic theologians apparently feel, from the acknowledgment that S. Peter had a daughter at all, was absolutely unknown in the earlier Christian centuries. To give an example. As late as the close of the eighth century, on an altar of a church in Bourges dedicated to the Blessed Virgin and other saints, there is an inscription attributed to Alcuin the scholar minister of Charlemagne. In this inscription occurs the following line:

“Et Petronilla patris præclari filia Petri.”

Now, towards the close of the fourth century, Pope Siricius, between A.D. 391 and A.D. 395, constructed the important basilica lately discovered in the Domitilla Cemetery on the Via Ardeatina; but although the basilica in question contained the historic tombs of the famous martyrs SS. Nereus and Achilles, confessors of the first century, as well as the body of S. Petronilla, he dedicated the basilica in question in her honour. Pope Siricius would surely have never named this important and very early church after a comparatively unknown member of the Flavian house; still less would he have called it by the name of a simple convert of the great apostle.

In Siricius’ eyes there was evidently no shadow of doubt but that the Petronilla for whom he had so deep a veneration was the daughter of S. Peter, and nothing but such an illustrious lineage can possibly account for the persistent devotion paid to her remains, a devotion which, as we have seen, endured for many centuries; the ancient tradition that she was the daughter of the apostle was evidently unvarying and undisputed.

It was left to the modern scholar in his zeal for the purity of the language he admired, and for the modem devout Romanist in his anxiety to show that S. Peter was free from all home and family ties, to throw doubts on the identity of one whom an unbroken tradition and an unswerving reverence from time immemorial regarded as the daughter of the great apostle so loved and revered in Rome.

In other places besides in Gaul and Rome we find traces of this very early cult of S. Petronilla. In the neighbourhood of Bury St. Edmunds her memory was anciently reverenced; under the curious abbreviation of “S. Parnel,” still in that locality, there is a church named after her—at Whepstead, Bury St. Edmunds. A yet more remarkable historical reference appears in “Leland’s Itinerary,” an official writing, be it understood, which dates circa A.D. 1539–40. Leland, writing of Osric, somewhile king of Northumbria, the founder of the famous Abbey of Gloucester, tells us how this King Osric “first laye in St. Petronell’s Chappel,” of the Gloucester Abbey. Osric died in the year of grace 729.

Thus before her body, at the instance of the Frankish King Pepin, was translated into the little imperial mausoleum hard by the great Basilica of S. Peter from her tomb on the Via Ardeatina, there was a Mercian chapel named after this Petronilla in the heart of the distant and only very imperfectly christianized Angle-land (England).

In the “Historia Monasterii S. Petri Gloucestriæ,” a document, or rather a collection of documents, of great value, we find an entry which tells us how Kyneburg, the sister of King Osric, and first abbess of the religious house of Gloucester, ruled the house for twenty-nine years, and, dying in A.D. 710, was buried before the altar of S. Petronilla; and later an entry in the same Historia relates that Queen Eadburg, widow of Wulphere, king of the Mercians, abbess of Gloucester from A.D. 710 to A.D. 735, was buried by the side of Kyneburg before S. Petronilla s altar. King Osric himself, who died in A.D. 729, was buried in the same grave as his sister Kyneburg, or as it is expressed in the “Historia,” “in ecclesia Sancti Petri coram altari sanctæ Petronillæ, in Aquilonari parte ejusdem monasterii.”

Professor Freeman quaintly comments here as follows: “It is certain that there was a church of some kind, a predecessor, however humble, of the great Cathedral Church (of Gloucester) that now is, at least from the days of Osric (circa A.D. 729). But more than this we cannot say, except that it contained an altar of S. Petronilla.”

APPENDIX II.—ON S. PETER’S TOMB

S. Peter’s Tomb.—While Pope Paul V’s task of destroying and rebuilding the eastern end of old S. Peter’s (the work of Constantine) was proceeding, somewhat before A.D. 1615 the same Pope designed to make the approaches to the sacred “Confession” of the apostle at the west end of the church more dignified, and it was in the course of building stairs and making certain excavations which were necessary to carry out his plans that his architect came upon a number of graves in the immediate neighbourhood of the walls which encircled the hallowed tomb of S. Peter. Here was evidently the old Cemetery of the Vatican which originally had been planned in the first century by Anacletus. Some memoranda of this discovery were made. But it was a few years later, when more important excavations were carried on in the pontificate of Pope Urban VIII (Cardinal Barberini) in connection with the foundations necessary for the support of the enormous baldachino of bronze over the high altar, that this most ancient cemetery was more fully brought to light.

The circumstances which led to these discoveries of Urban VIII were as follows: The date is about A.D. 1626; Bernini was the architect in the Pope’s confidence, and it was determined to replace the existing canopy over the altar and confession, which was considered too small and insignificant for its position, by the great and massive bronze baldachino which now covers the high altar and the confession leading to the sacred tomb.

The materials for this mighty canopy and its pillars were obtained from the portico of the Pantheon, the roof of the portico of that venerable building being stripped of its gilded bronze. This portico had survived from the days of its builder Agrippa, the son-in-law of the Emperor Augustus.

The act of Urban VIII, thus robbing one of the remaining glories of ancient Rome, was severely criticised in his day, and the well-known epigram survives to commemorate this strange act of late “vandalism”: “Quod barbari non fecerunt, fecit Barberini.”

The new baldachino or canopy of Bernini’s was 95 feet in height, and is computed to weigh nearly 100 tons. To support this enormous weight of metal it was judged necessary to construct deep and extensive foundations. It was in the digging out and building up of these substructures in the immediate vicinity of the apostle’s tomb that the remarkable discoveries we are about to relate were made.

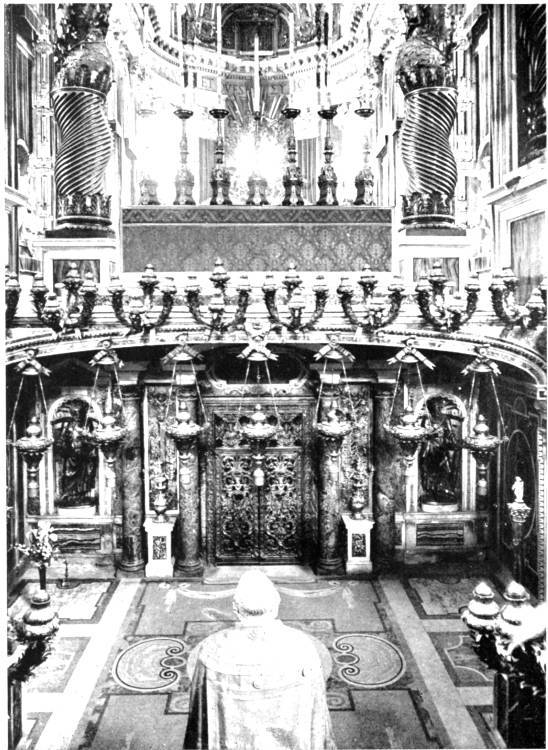

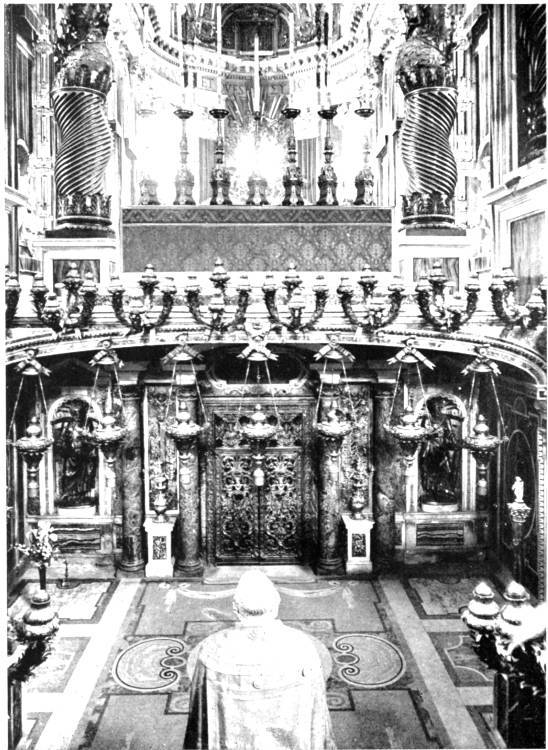

S. PETER’S, ROME—THE CONFESSION. 95 EVER-BURNING LAMPS ARE IN FRONT OF THE ENTRANCE TO THE APOSTLE’S TOMB

The account from which we quote is virtually a semi-official procès-verbal, and was compiled by an eye-witness—Ubaldi, a canon of S. Peter’s, who was present when the discoveries were made, and who has left us his notes made on the spot and at the time. Singularly enough, the memoranda of Ubaldi lay disregarded, hidden among the Vatican archives until comparatively recently. They were found[132] by one of the keepers of these archives, and have been published lately by Professor Armellini.

Before, however, giving the extracts from Ubaldi’s memoranda of the discoveries in the Cemetery of Anacletus in the year 1626, it will be of material assistance to the reader if a short account of the probable present position and state of the great apostle’s tomb is subjoined. It will be borne in mind that the excavations in connection with Bernini’s baldachino were carried out close to the tomb in question.

The vault, in which we believe rests the sarcophagus which contains the sacred remains of the apostle, lies now deep under the high altar of the great church. It was always subterranean, and no doubt from the earliest days was visited by numbers of believers belonging not only to the Roman congregation, but by pilgrims from many other countries. Pope Anacletus, to accommodate these numerous pilgrim visitors, built directly over the tomb a little Memoria or chapel. This apparently was done by raising the walls of the vault beneath, and thus a chamber or chapel above was provided. This Memoria of Anacletus is generally known as the confession. Both these chambers now lie beneath the floor of the existing church. Originally the Memoria of Anacletus above the chamber of the tomb showed above ground; it is no doubt the “Tropæum” alluded to by the Presbyter Caius, circa A.D. 210.

Roughly, the height of the two chambers from the floor of the original vault to the ceiling of the Memoria built over it is some 32 feet. There is little difference in the height of each of these two chambers.

The probable explanation of the details given in the Liber Pontificalis of the works of Constantine the Great at the tomb is as follows: Both the chambers of the tomb—the original vault and the Memoria of Anacletus over it—were left intact, but with certain added features, simply devised with the view of strengthening and ensuring the permanence of the sacred spot and its contents. The whole of the chamber of the tomb was then filled up with solid masonry, except immediately above the sarcophagus.

The upper chamber, the Memoria, was strengthened with masses of masonry on each side, so as to bear the weight of a great altar, the high altar of the Basilica of Constantine, which was erected so as to stand immediately over the body of S. Peter. A cataract or billicum, as it is sometimes called, covered with a bronze grating, opened from above close to the altar. There are two of these little openings, one leading into the Memoria, and the other from the Memoria to the chamber of the tomb beneath. Through these openings handkerchiefs and such-like objects would be lowered so as to touch the sarcophagus. This we know was not unfrequently permitted in the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth centuries. Such objects after they had touched the coffin were esteemed as most precious relics.

In addition to these works in the two chambers, the Emperor Constantine enclosed the original stone coffin which contained the remains of S. Peter in bronze, and laid upon this bronze sarcophagus the great cross of gold—the gift of his mother Helena and himself. This is the cross which Pope Clement VIII and his cardinals saw dimly gleaming below, when an opening to the tomb was suddenly disclosed in the great building operations which were carried out during the last years of the sixteenth century.

There is scarcely room now for doubt that the bronze coffin and the golden cross are still in the chamber of the tomb where Constantine placed them.

When it was found necessary to excavate for the foundation of the new massive baldachino, Pope Urban VIII was alarmed at first lest the sacred tomb should be disturbed. The warnings of Pope Gregory the Great against meddling with the tombs of saints like Peter and Paul being remembered, “no one dare even pray there,” he once wrote, “without much fear.” Three years were spent in preparation for the work and in casting the baldachino. Then the sudden death of Alemanni, the custodian of the Vatican library, who had the chief charge in the preparative work, and the passing away of two of the Pope’s confidential staff just as the work commenced, appalled men’s minds; but after some hesitation it was decided to go on with the necessary excavations—“All possible precautions,” Ubaldi tells us, “being taken for the preservation of the reverence due to the spot, and for the security of the relics.” The Pope commanded, “that while the labourers were at work there should always be present some of the priests and ministers of the Church.”

Ubaldi describes at length what was found, when each of the four foundations for the four great columns of the baldachino was dug out. We will quote a few of Ubaldi’s memoranda, and then give a little summary of what apparently was discovered in this perhaps the most ancient, certainly the most interesting, of the subterranean cemeteries of Christian Rome.

In the excavation of the first foundation—“only two or three inches under the pavement they began to find coffins and sarcophagi. Those nearest to the altar (above) were placed laterally against an ancient wall” (this was doubtless part of the wall of the Memoria of Anacletus), “and from this they judged that these must be the bodies buried nearest to the sepulchre of S. Peter. These were coffins of marble made of simple slabs of different sizes.” Only one seems to have borne an inscription, and that was the solitary word “Linus.” Was not this the coffin of the first Pope, the Linus saluted in S. Paul’s Roman Epistle?

“Two of these coffins were uncovered. The bodies, which were clothed with long robes down to the heels, dark and almost black with age, and which were swathed with bandages, ... when these were touched and moved they were resolved into dust.... We can only conclude that those who were found so close to the body of S. Peter must have been the first (Martyr) Popes or their immediate successors....

“On the same level, close up to the wall (of the Memoria) were found two other coffins of smaller size, each of which contained a small body, apparently of a child of ten or twelve years old.” “Were these, whose bodies had obtained the privilege of interment so close to the grave of S. Peter, little martyrs?... Close by ... were two (coffins) of ancient terra-cotta full of ashes and burnt bones, ... other fragments of similar coffins were found deeper down as the excavations proceeded, and also pieces of glass from broken phials. It was evident that all this earth was mixed with ashes and tinged with the blood of martyrs.... There were also found pieces of charred wood which one might believe had served for the burning of the martyrs, and had afterwards been collected as jewels and buried there with their ashes.”

A little farther on Ubaldi writes, still speaking of what was found where the first foundation was excavated: “There was next found a small well in which were a great number of bones mixed with ashes and earth; then again another coffin; near this was found another square place on the sides of which more bodies were found, while on one side was the continuation of a very ancient wall (the Memoria of Anacletus). This wall contained a niche which had been used as a sepulchre, and in it were found five heads fixed with plaster and carefully arranged, also being well preserved. Lower down were the ribs all together, and the other parts in their order mingled with much earth and ashes, not laid casually, but with accuracy and great care. All this holy company were shut in and well secured with lime and mortar....

“It now became necessary to consider how the holy bones and bodies which had been taken up might best be laid in some fitting and memorable place; they had been placed in several cases of cypress wood, and had been carried before the little altar of S. Peter in the confession, and here all through these days they had been kept locked up and under seal. It was felt that they ought not to be deprived of the privilege of being near to the body of S. Peter.... So it was resolved that, as they had been found buried together and undistinguished by names, so still one grave should hold them all, since the holy martyrs are all one in eternity,”—as S. Gregory Nazianzen wonderfully says—“ ... a suitable and capacious grave was constructed” (close to the spot) “and there re-interment took place. The following inscription cut in a plate of lead was placed within the tomb—

Corpora Sanctorum prope sepulchrum sancti Petri inventa, cum fundamenta effoderentur æreis Columnis (of the baldachino of Bernini) ab Urbano VIII—super hac fornice erectis, hic siul collecta et reposita die 28 Julii 1626”

In digging for the second foundation a very wonderful “find” was recorded. Ubaldi relates how, “not more than three or four feet down, there was discovered at the side a large coffin made of great slabs of marble.... Within were ashes with many bones all adhering together and half burned. These brought back to mind the famous fire in the time of Nero, three years before S. Peters martyrdom, when the Christians, being falsely accused of causing the fire, and pronounced guilty of the crime, afforded in the circus of the gardens of Nero, which were situated just here on the Vatican Hill, the first spectacles of martyrdom. Some were put to death in various cruel ways, while others were set on fire, and used as torches in the night, thus inaugurating on the Vatican, by the light that they gave, the living splendour of the true religion.... These, so they say, were buried close to the place where they suffered martyrdom, and gave the first occasion for the religious veneration of this holy spot.... We therefore revered these holy bones, as being those of the first founders of the great basilica and the first-fruits of our martyrs, and having put back the coffin allowed it to remain in the same place.”

With great pathos Mr. Barnes, from whose translation of the Ubaldi Memoranda on the discoveries in the Cemetery of Anacletus these extracts are taken, describes the scene of the interment of these sad remains of the martyrs in the games of Nero. We quote a passage specially bearing on this strange and wonderful “find,” where, after describing what took place in the famous games, he went on thus:

“The horrible scene drew to a close at last; the living torches, burning slowly, flickered and went out, leaving but a heap of ashes and half-burnt flesh behind them; the crowds of sightseers wended their way back to the city, and silence fell again on the gardens of Nero. Then there crept out through the darkness, within the circus and along the paths of the gardens, a fresh crowd—men and women, maidens and even little children, taking every one of them as they went their lives in their hands, for detection meant a cruel death on the morrow; eager to save what they could of the relics of the martyrs: bones that had been gnawed by dogs and wild beasts; ashes and half-burnt flesh, and other sad remnants, all of them precious indeed in the sight of their brethren who are left, relics that must not be lost.... Close by the circus, on the other side of the Via Aurelia, some Christians had already a tiny plot of ground available for purposes of burial. There on the morrow, in a great chest of stone, were deposited all the remains that could be collected; for it was out of the question to keep them separate one from another.” It was the beginning of the Vatican Cemetery, hereafter to become so famous. “ ... More than 1600 years afterward, when the excavations were being made for the new baldachino over the altar tomb of S. Peter himself, the sad relics of this first great persecution were brought to light. But they were not disturbed, and still rest in the place where they were originally laid, where now rises above them the glorious dome of the first Church of Christendom.”

In the memoranda on the third foundation there is nothing of very special interest to note.

On the fourth foundation Ubaldi wrote the following strange and peculiarly interesting note: “Almost at the level of the pavement there was found a coffin made of fine and large slabs of marble.... This coffin was placed, just as were the others which were found on the other side, within the circle of the presbytery, in such a manner that they were all directed towards the altar like spokes toward the centre of a wheel. Hence it was evident with how much reason this place merited the name of ‘the Council of Martyrs.’ ... These bodies surrounded S. Peter just as they would have done when living at a synod or council.”

These apparently were the remains of the first Bishops or Popes of Rome, for whom Anacletus made special provision when he arranged this earliest of cemeteries. Their names are, Linus whose coffin lies apart but still close to the apostle’s tomb, Anacletus, Evaristus, Sixtus I, Telesphorus, Hyginus, Pius I, Eleutherius, and Victor. Victor was laid in this sacred spot in the year of grace 203. After him no Bishop of Rome was interred in the Cemetery of Anacletus on the Vatican Hill. Originally of but small dimensions, by that date it was filled up, and the successors of Pope Victor, we know, were interred in a chamber appropriated to them in the Cemetery of S. Callistus in the great Catacomb so named on the Appian Way.

The other interments in the sacred Vatican Cemetery in the immediate neighbourhood of the apostle’s tomb—some of the more notable of which have been noticed in our little extracts from the Ubaldi Memoranda—were apparently the bodies or the sad remains of martyrs of the first and second centuries of the Christian era, or in a few cases of distinguished confessors of the Faith whose names and story are forgotten, but to whom Prudentius (quoted on p. 216) has alluded.

There is an invaluable record of what lies beneath the high altar and the western part of the great Mother Church of Christendom.

In a rare plan of this Cemetery of the Vatican drawn by Benedetto Drei, Master Mason of Pope Paul V, which apparently was made during the period of the first discoveries under Paul V, some time between A.D. 1607 and 1615, and which has received certain later corrections no doubt after the second series of discoveries consequent upon the excavations for the foundations in the neighbourhood of the tomb of S. Peter, for the great bronze baldachino of Bernini in the days of Pope Urban VIII, about A.D. 1626.

This plan of Drei is most valuable, though not accurate in detail. It marks the position of some of the graves which were found, but not of all that were disclosed in the second series of discoveries under Urban VIII. It was not issued until A.D. 1635. This later date explains the corrections which have been inserted.