PART II

TWO EXAMPLES OF RECENT DISCOVERIES

CRYPT OF S. CECILIA—THE BURIAL-PLACES OF S. FELICITAS, OF JANUARIUS, AND OF HER OTHER SONS

I

Out of the many pages of Catacomb lore, the story of the Crypt of S. Cecilia and its recent discovery, and the identification of the burial-places of S. Felicitas and her seven sons, have been selected to be told here as specially interesting examples of the historical and theological importance of these investigations among the forgotten cemeteries of subterranean Rome.

Allard’s words in his edition of Northcote and Brownlow’s exhaustive résumé of a portion of De Rossi’s monumental work, deserve quoting. Writing of S. Cecilia, he says:

“Les découvertes modernes l’ont bien vengée du scepticisme ou de la prudence excessive de Tillemont: on sait aujourd’hui que Sainte Cecile n’est ni un mythe, ni une martyre venue de Sicile, mais une vraie Romaine, du plus pur sang romain; sa noble et gracieuse figure est décidément sortie des brumes de la légende pour entrer dans le plein jour de l’histoire.”

The “Acts” of her martyrdom in their present form are probably not older than the fifth century, although S. Cecilia suffered in the reign of the Emperor Marcus Antoninus, circa A.D. 177. But these “Acts” are undoubtedly very largely based upon a contemporaneous record: the recent discoveries have enabled historical criticism fairly to restore what was original in the story of the martyr.

Cecilia was a noble Roman lady, who belonged to a family of senatorial rank; her father apparently was a pagan, or if a Christian at all was a man of the world rather than an earnest believer, for he gave his daughter in marriage to a young patrician, one Valerianus, a pagan, but a pagan of the highest character. Cecilia was a devoted Christian: at once she induced her husband and his brother Tiburtius to abjure idolatry. Accused of Christianity at a moment when the Government of the Emperor Marcus was determined to stamp out the fast-growing religion of Jesus, the two brothers were condemned to death, and they suffered martyrdom in company with the Roman officer who presided at their execution, and who, beholding the constancy of the two young patricians, embraced the faith which had enabled them to witness their good confession.

Cecilia shared in their condemnation. The Government, however, dreading the example of the death of so prominent a personage in Roman society, determined to put her to death as privately as possible. She was doomed to die in her own palace. The furnaces which heated the baths were heated far beyond the usual extent, and Cecilia was exposed to the deadly and suffocating fumes. These failed in their effect: after being exposed in her chamber for a night and a day to these fumes, she was still living, apparently unharmed. The Prefect of the city, who was in charge of Cecilia’s execution, then gave orders to a lictor to decapitate the young Christian lady who persistently refused to abjure her religion.

There is nothing improbable in the story, which goes on to relate how the executioner, unnerved with his grim task, inflicted three mortal wounds, but Cecilia, though dying, yet breathed and preserved consciousness.

The Roman law forbade more than three strokes with the sword, and she lived on for two days and nights, during which long protracted agony she was visited by her friends, among whom was a Bishop Urbanus, not the Urbanus Bishop of Rome, as the “Acts” with some confusion tell us, but another Urbanus, probably a prelate of some smaller see.

After she had passed away, her body with all care and reverence was laid in a sepulchral chamber which subsequently became part of the great Cemetery of Callistus. The martyr was interred evidently in a vault or crypt which belonged to her illustrious family; several inscriptions belonging to Christian members of the gens Cæcilia have been found in the immediate vicinity of S. Cecilia’s grave. Less than a quarter of a century after her martyrdom, the subterranean cemetery in which the Cæcilian vault was situated became part of the general property of the Roman congregations. Callistus, afterwards Bishop of Rome, held a high office under Bishop Zephyrinus, and he was set over the cemetery, which was subsequently called after him, the Cemetery of Callistus. At the beginning of the third century—as in the Vatican Crypt, where the earliest Bishops of Rome had been deposited round the body of S. Peter, there was no more room for interments—Callistus arranged the sepulchral chamber known as the Papal Crypt to be the official burying-place of the Bishops of Rome. The chamber in which S. Cecilia was laid was close by this Papal Crypt. De Rossi graphically expresses this: “Ce n’est donc pas sainte Cecile qui fut enterrée parmi les Papes, c’est elle au contraire qui fit aux Papes du IIIme siècle les honneurs de sa demeure funèbre.” (From Allard.)

We will trace the story of the celebrated Roman saint through the ages.

The statement contained in the “Acts of S. Cecilia” of her interment in the Cemetery of S. Callistus no doubt is accurate, although the hand of a somewhat later “redactor” is manifest, for the cemetery only obtained its title of “Callistus” some thirty years after the martyrdom of the saint. S. Cecilia at once seems to have won a prominent place among the martyrs and confessors of the persecution of Marcus Aurelius. This is accounted for not only by the dramatic scenes which a generally accepted tradition tells us were the accompanying features of her passion, but also by the high rank and position of the sufferer and her generous bequest to the Roman congregations.

Towards the close of the fourth century S. Cecilia’s crypt was among the popular sanctuaries specially cared for by Pope Damasus, much of whose work is still, in spite of centuries of neglect, clearly visible. Damasus’ work here was by no means confined to decoration, but included elaborate arrangements for the visits of pilgrims to the shrine, such as a special staircase and considerable masonry work to secure the walls and approaches. Somewhat later, Pope Sixtus III, A.D. 432–40, continued and amplified the decoration and constructive improvements of his predecessor Damasus.

The decorations and paintings of this crypt, as at present visible, clearly date from the fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries. De Rossi considers that the existence of these successive decorations, and the fact that various works, constructive as well as ornamental, were evidently at different epochs executed here, tell us that this is an historic sepulchral chamber highly venerated by many generations of pilgrim visitors.

From very early times, most probably from the days of the Emperor Marcus, there has been a church traditionally constructed on the site of an ancient house, the house of the martyr Valerian, Cecilia’s husband. Recent investigations, have gone far to substantiate the ancient tradition, for beneath the existing Church of S. Cecilia portions of an important Roman house of the second century have come to light.

The church, originally a private house of prayer, at a very remote period became a public basilica. It had fallen into a ruinous condition, and was rebuilt by Pope Paschal I in the ninth century. This restoration of the old basilican church no doubt suggested to Paschal his inquiry after the remains of the loved martyr in whose memory the church had been originally dedicated. The dramatic and well-authenticated story of the finding of the body by Paschal is as follows:

II

The great translation of the remains of the 2300 martyrs and confessors from the catacombs into the city for the sake of protecting these precious relics from barbarian pillage took place in the days of Pope Paschal I (ninth century). When this translation was going on, Paschal made an inquiry after the burying-place of S. Cecilia. Although the lengthy entry in the Liber Pontificalis makes no mention of any special reason for this investigation, there is no doubt but that the restoration work which was being carried on at the basilica of the saint across the Tiber suggested it to the Pope. The tomb of the famous saint could not be found, although for centuries it had been emphatically alluded to in several of the Pilgrim Itineraries, and in the yet more ancient “Guide,” subsequently copied by William of Malmesbury several centuries later.

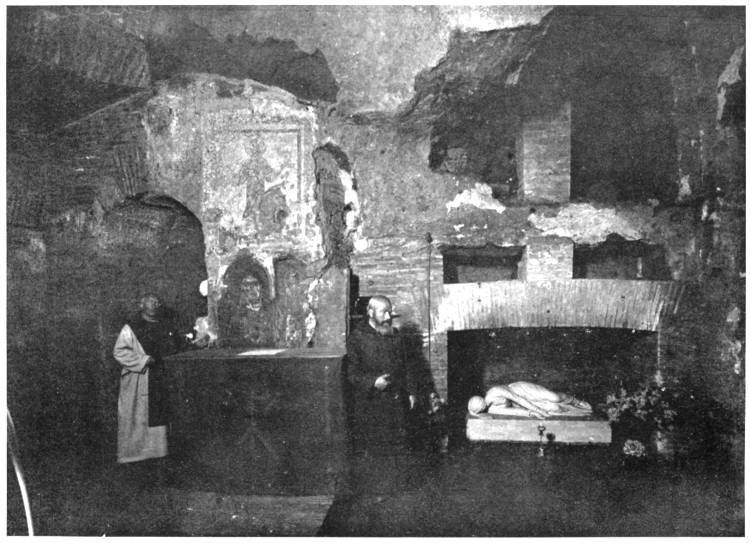

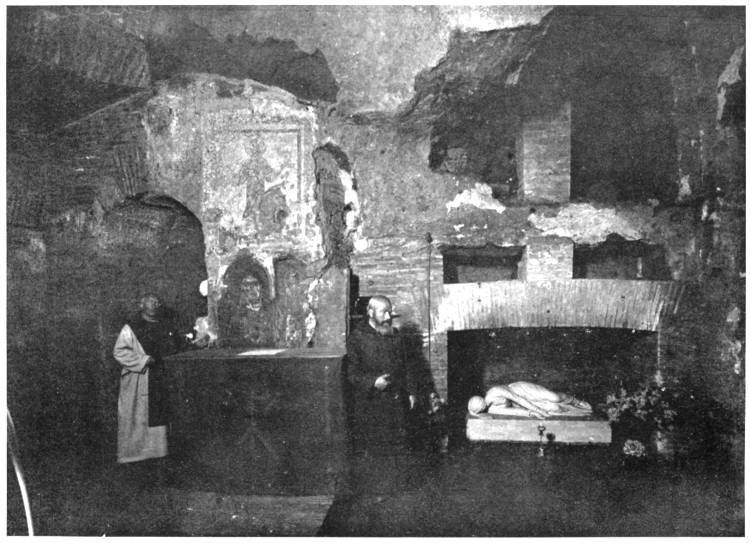

A REPLICA OF MADERNO’S EFFIGY OF S. CECILIA—AS SHE WAS FOUND—IS IN THE NICHE OF THE S. CALLISTUS CATACOMB CHAMBER—WHERE THE BODY ORIGINALLY WAS DEPOSITED

It was about the year of grace 821, after long and fruitless searching for the lost tomb, and when he had come to the conclusion that the body of S. Cecilia had been carried away probably by Astolphus and the Lombards in their destructive raids, and that the tomb had been destroyed, that Pope Paschal early one morning, while listening to the singing of the Psalms in the great Vatican Basilica, fell asleep; as he slept he saw the form of a saint in glory; she disclosed her name, “Cecilia,” and told him where[133] to look for her tomb.

Acting upon the words of the saint in the vision, he found at once the lost tomb, and when the coffin of cypress wood was opened, the body of Cecilia was seen unchanged, still wrapped in the gold-embroidered robe in which she had been clothed when her loving friends laid her to rest after her martyrdom, with the linen cloths stained with her blood folded together at her feet.

She lay in the position in which she had passed away. Those who had buried her, left her thus—not lying upon the back like a body in a tomb, but upon the right side, with her knees drawn together and her face turned away—her arms stretched out before her. In her touching and graceful attitude she seemed as though she was quietly sleeping.

Just as he found her, in the same coffin with the robe of golden tissue and the blood-stained linen folded by her feet, Pope Paschal reverently deposited her in a crypt beneath the altar of her church in the Trastevere district, simply covering the body with a thin veil of silk.

Nearly eight hundred years after (A.D. 1599), Sfondrati, titular Cardinal of the Church, while carrying out some works of restoration and repair in this ancient Church of S. Cecilia, came upon a large crypt under the high altar. In the crypt were two ancient marble sarcophagi. Responsible witnesses were summoned, and in their presence the sarcophagi were carefully opened. In one of these the body of S. Cecilia lay just as it had been seen eight centuries before by Pope Paschal I—in the same pathetic attitude, robed in gold tissue with the linen cloths blood-stained at her feet.

Every care was taken by the reigning Pope Clement VIII to provide careful witnesses of this strange discovery; among these were the famous scholars Cardinal Baronius and Bosio; the greatest artist of the day, Stefano Maderno, was summoned to view the dead saint and to execute the beautiful marble portrait which now lies in the recess of the Confession beneath the high altar of the well-known church in the Trastevere at Rome. In an inscription, Maderno, the artist, tells how he saw Cecilia lying incorrupt and unchanged in her tomb, and how in the marble he has represented the saint just as he saw her.[134]

The second sarcophagus found by Cardinal Sfondrati in the crypt of the Church of S. Cecilia beneath the high altar, was also opened by him. It was found to contain the bodies of three men, who had clearly suffered violent deaths—two of them had been decapitated, and the third had evidently been beaten to death by a horrible means of torture sometimes used—the “plumbatæ”—leathern or metal thongs loaded with lead; one of these, which evidently had been used in the death-scene of a martyr, was found in a crypt of this cemetery. These three were no doubt the remains of SS. Valerianus (the patrician husband of S. Cecilia), Tiburtius his brother, and the Roman officer Maximus, whose remains, brought no doubt by Pope Paschal I from the Prætextatus Cemetery where we know they had been interred, were deposited by him in the crypt of the Church of S. Cecilia close to the body of the famous martyr with whom they were so closely and gloriously connected.

The story of the discovery and certain identification of the original sepulchral chamber of S. Cecilia is vividly told by De Rossi with great detail. It was one of his important “finds.” With the tradition before him—with the clear references in the pilgrim traditions—the great archæologist was sure that somewhere in the immediate vicinity of the sepulchral chamber of the Popes or Bishops of Rome of the third century, must be sought the crypt where S. Cecilia lay for more than six centuries.

First he discovered that adjoining the official Papal Crypt was another chamber, evidently of considerable size, in which a luminare[135] had been constructed, but the chamber and the luminare were choked up with earth and ruins. He proceeded to excavate the latter; as the work proceeded, the explorers in the neighbourhood of the chamber came upon the remains of paintings.

Lower down, almost on the level of the chamber, these paintings became more numerous and more distinct. The work of digging out went on slowly; more paintings had evidently once decorated that ruined and desolate chamber of death—one of them, a woman richly dressed, obviously represented S. Cecilia. Another of a bishop inscribed with the name of S. Urbanus, the bishop connected with the story of the saint. The paintings were of different dates, some as late as the seventh century. A door which once led into the Papal Crypt was found: remains of much and elaborate decorative work were plainly discerned, work of various ages, belonging some of it to the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries.

In one of the walls of the chamber a large opening had been originally constructed to receive the sarcophagus of the martyr.

All showed clearly that this had once been a very famous historic crypt, the resort of many generations of pilgrims, and its situation answered exactly to what we read in the Pilgrim Itineraries, in the Liber Pontificalis, and in other ancient authorities as the situation of the original burying-place of S. Cecilia. The subjects, too, of the dim discoloured paintings pointed to the same conclusion.

In the immediate neighbourhood of the sepulchral chamber De Rossi counted some twelve or thirteen inscriptions telling of Christian members of the “gens Cæcilia” who had been buried there—all testifying to the fact that originally this portion of the great group of the so-called “Callistus” Catacomb was the property of the noble house in question, and that probably at an early date it had been made over to the Christian Church in Rome. The saint and martyr therefore had been laid amidst the graves of other members of her family.[136]

In the chain of testimony which has been brought together one link seems to call for an elucidation. How is it that Pope Paschal I failed at first to discover the sepulchral chamber of S. Cecilia, considering it lay so close to the famous Papal Crypt, and in fact communicated with it? The answer is that no doubt at some time previous to his research the crypt of S. Cecilia had certainly been “walled up,” “earthed up,” or otherwise concealed to protect this revered sanctuary from the prying eyes and sacrilegious hands of Lombards and other barbarian raiders. It must be remembered that for centuries the tomb of S. Cecilia had been one of the principal objects of veneration in this great cemetery. Signs of this later work of concealment were also discovered by De Rossi.

De Rossi, in his summing up, comes to the conclusion that no doubt whatever rests upon the identification of the original burying-place of S. Cecilia, and that the sepulchral chamber discovered by him adjoining the Papal Crypt was the spot where her sarcophagus lay for centuries—the actual chamber which was subsequently adorned and made accessible by Pope Damasus; which was further decorated by several of his successors in the papacy; and which was visited and venerated by successive generations of pilgrims from all lands.

In the ninth century the sarcophagus containing the sacred remains was translated as we have seen by Pope Paschal I, and brought to the ancient Basilica of S. Cecilia in the Trastevere, where it has rested securely ever since. In the year 1699 it was seen and opened and its precious contents inspected by Pope Clement VIII, by Cardinal Sfondrati, by Cardinal Baronius, by Bosio and others, as we have related.

After the translation in the ninth century, the original crypt, in common with so many of the catacomb sanctuaries, was deserted and allowed to go to ruin—utterly forgotten until De Rossi rediscovered it and reconstructed its wonderful history.

Writing in the earlier years of the twentieth century, Marucchi, the follower and pupil of De Rossi, in his latest work on the Catacombs, reviews and fully endorses the conclusions of his great master on the question of the tradition of S. Cecilia’s tomb.

What we stated at the beginning of this little study is surely amply verified. S. Cecilia and her story no longer belong to mere vague and ancient tradition, but live in the pages of scientific history.

III

We will cite another example, and a yet more striking one, of the light thrown by the witness of the catacombs on important questions which have been gravely disputed, in connection with the history of the very early years of Christianity.

Ecclesiastical historians of the highest rank have gravely doubted the truth of the story of the martyrdom of S. Felicitas and her seven sons[137] in the days of the Emperor Marcus about the middle of the second century. The splendid constancy in the faith of the mother and of her hero sons, in the opinion of these grave and competent critics was a recital almost entirely copied from the record of the Maccabean mother and her seven brave sons, and so the Passion of S. Felicitas and her sons has been generally consigned to the shelf of early legendary Christian history; few historians would venture to quote as genuine this pathetic and inspiring chapter of the persecution of the Emperor Marcus. It is regarded as a piece of literature, devised in the sixth century or even later, and quite outside serious history.

But recent investigations in the great subterranean city of the Roman dead have completely changed this commonly held view, and the episode in question must now take its place among the acknowledged Christian records of the middle of the second century. She belonged to the ranks of the great ladies of Rome; her husband, of whom we know nothing, was dead, but Felicitas and her sons were well known in the Christian community of the capital, where she was distinguished for her earnest and devoted piety.

Her high rank gave her considerable influence, and she was in consequence dreaded by the pagan pontiffs. These high officials, aware of the Emperor Marcus Antoninus’ hostility to the Christians, laid an information against the noble Christian lady as belonging to the unlawful religion. They represented her as stirring up the wrath of the immortal gods by her powerful influence among the people. Marcus at once directed the Prefect of the city, Publius, to see that Felicitas and her sons sacrificed in public to the offended deities. This was in the year of grace 162.

The “Acts of the Passion,” from which we are quoting here, no doubt with very little change represent the official notes or procès-verbal of the interrogatory at the trial.

The Prefect Publius at first with great gentleness urged her to sacrifice, and then finding her obdurate, threatened her with a public execution.

Finding persuasion and threats of no avail, Publius urged her, “If she found it pleasant to die, at least to let her sons live.” Felicitas replied that they would most certainly live if they refused to sacrifice to idols, but if they did sacrifice, they would surely die—eternally.

The public trial subsequently took place in the open Forum; again the Roman magistrate urged the mother to be pitiful to her sons, still in the flower of their youth, but the brave confessor, turning to the young men, told them to look up to heaven—there Christ with His saints was waiting for them: “Fight,” she said, “my sons, the good fight for your souls.”

The young men in turn were placed before him. The Prefect in the name of the Emperor offered them each a splendid guerdon and coveted privileges at the Imperial court if they would only consent to sacrifice publicly to the gods of Rome. One and all of the seven refused, preferring to die with their noble mother, choosing the other guerdon, the alternative guerdon offered in the name of the great Emperor, the fearful and shameful deaths to which an openly professing Christian in the days of Marcus was condemned by the stern Roman law.

The interrogatory and the noble answers of mother and sons as contained in the “Acts of the Passion of S. Felicitas,” are at once a stirring and pathetic recital.

The final condemnation naturally followed. The death sentences were confirmed by the Emperor, and sternly carried out.

Felicitas and her seven sons suffered martyrdom,[138] and through pain and agony passed to their rest and bliss in the Paradise of their adored Master Christ.

Around these “Acts” a continual war of criticism has been waged: the question has by no means as yet been positively decided.

Tillemont hesitatingly expresses an opinion that they have not all the characteristics of genuine “Acts.” Bishop Lightfoot is yet more positive in his view that they are not authentic. Aubé repeats a similar judgment. On the other hand, De Rossi, Borghesi, and Doulcet accept them as genuine. But all are agreed that they are very ancient. The interrogatory portion is no doubt a verbatim extract from the original procès-verbal.

The piece appears to have been originally largely written in Greek, but Gregory the Great, who refers to it, speaks of another and better text which we do not possess. One striking indication of its great antiquity is that no mention is made of the tombs of the martyrs. Had these “Acts” dated even from the fifth century this would not have been omitted, for in the fifth century the martyrdoms had obtained great celebrity.

A very early mention of these tombs, however, we find in the so-called “Liberian” or “Philocalian” Catalogue, which was partly composed or put together not later than the year of grace 334. The alternative name of the Catalogue is derived from Filocalus, the famous calligrapher of Pope Damasus, who most probably was the compiler of the work, which consists of several tracts chronological and topographical of the highest interest, some originally doubtless composed at a very early date. It contains, among other pieces, a Catalogue of Roman Bishops, ending with Liberius, and a piece termed “Depositio Martyrum,” in which the burying-places of the seven sons of Felicitas are carefully set out. This ancient memorandum has been of the greatest assistance to De Rossi and Marucchi in their identification of the original graves of the “seven.”

When De Rossi had penetrated into the cemetery of Prætextatus on the Appian Way, he came upon what was evidently a highly decorated chamber, once lined with marble, and carefully built and ornamented. It was, he saw, an historic crypt of the highest interest. The vault of the chamber was painted, and the fresco decorations were still fairly preserved. The paintings represented garlands of vines and laurels and roses, executed with great taste and care; the style and execution belonged to work which must be dated not later than the second century. Below the beautifully decorated vault was a long fresco painting of the Good Shepherd with sheep; one sheep was on his shoulders. This painting has been sadly interfered with by a loculus, or grave, of later date, probably of the fourth or fifth century; on the loculus in question could still be read the following little inscription—perfect save for the first few letters:

. . MI RIFRIGERI JANUARIUS AGATOPUS FELICISSIM

. . . MARTYRES

Some sixth-century Christians, anxious to lay their beloved dead close to the martyrs, had caused the wall of the chamber to be cut away, for the reception of the body, regardless of the painting, and then while the plaster was still fresh had cut these words of prayer, which may be translated, “May Januarius, Agatopus,[139] and Felicissimus refresh (the soul of ...).” Agatopus and Felicissimus were two of the deacons of Pope Sixtus II, who had (probably in the same catacomb) suffered martyrdom, A.D. 258. Their sepulchral chambers were subsequently identified.

The question at once presented itself to De Rossi—was not this chamber ornamented with paintings clearly of the second century, the crypt where S. Januarius had been laid? All doubt on this point was subsequently cleared up, for eventually in many fragments the original inscription which Pope Damasus had caused to be placed over the door or near the altar was found. The inscription ran thus:

BEATISSIMO · MARTYRI

JANUARIO

DAMASUS · EPISCOP ·

FECIT

The body of S. Felicitas the mother was laid in the cemetery in the Via Salaria Nova which bears her name. After the Peace of the Church towards the end of the first quarter of the fourth century, a little basilica was erected over the spot in the catacomb in question where the remains of the martyred mother had been deposited. As late as A.D. 1884, while digging the foundations of a house, the little basilica was discovered—in Marucchi’s words, “on y reconnut aussitôt le tombeau de Ste Felicité.” Paintings of the mother and her sons adorn the walls. Beneath the basilica was a crypt in which the Salzburg Itinerary tells us lay her youngest son S. Silanus: the words of this Pilgrim Itinerary run thus: “Illa pausat in ecclesia sursum et filius ejus sub terra deorsum.”

At the end of the eighth century Pope Leo III translated the remains of the mother and son to the Church of S. Suzanna, near the Baths of Diocletian, where they still rest.

In the Philocalian or Liberian Calendar, A.D. circa 334, an entry appears under the heading of “Depositio Martyrum,” telling how two more of the seven martyred sons of Felicitas were buried in the Cemetery of S. Priscilla, namely, SS. Felix and Philip.

After the Peace of the Church, the basilica subsequently known as S. Sylvester was erected over a portion of the great Priscilla Cemetery, and many of the bodies of the more famous martyrs were brought up from the subterranean galleries and chambers and buried in conspicuous places in the new Basilica of S. Sylvester; amongst these were the remains of the two sons of Felicitas, SS. Felix and Philip. This is carefully described in the Pilgrim Itineraries or Guides. These two well-known martyrs were deposited under the high altar of S. Sylvester. In the second Salzburg Itinerary, known as “De locis SS. Martyrum,” they are thus specially mentioned: “S. Felicis [sic] unus de septem et S. Philippus unus de septem,” and in William of Malmesbury, copying from a much older Itinerary, we read, “Basilica S. Silvester ubi jacet marmoreo tumulo co-opertus ... Martyres ... Philippus et Felix.” Marucchi thinks he can point out the tomb in the subterranean crypt where the two originally were laid.

The three remaining sons of Felicitas, namely, SS. Alexander, Vitalis, and Martialis, were interred in the cemetery of the Jordani on the Via Salaria Nova. This cemetery, owing to its state of ruin and the difficulty of pursuing the excavating work, has only been very partially explored; but Marucchi believes he has found a broken inscription referring to “Alexander, one of the seven brothers.” It is probable that other traces of the loculi of these three will come to light when this large but comparatively little known catacomb, which is in a very ruinous and desolate condition, is carefully examined: at present large portions of it are quite inaccessible.

The second Salzburg Itinerary “De locis SS. Martyrum” specially guides the pilgrim to tombs of these three thus: “propeque ibi” (alluding to the Basilica of S. Chrysanthus and Daria built over a portion of the Cœmeterium Jordani) “S. Alexander et S. Vitalis, sanctusque Martialis qui sunt tres de septem filiis Felicitatis ... jacent.” William of Malmesbury in his transcript of an ancient Itinerary also mentions them, as do other of the Pilgrim Guides.

In the celebrated “Monza” Catalogue and in the “Pittacia,” or small labels, belonging to the phials which contained a little of the sacred oils which were burnt before the tombs of the more eminent confessors and martyrs (the phials of oils which were sent by Pope Gregory the Great (A.D. 590–604) to Theodelinda the Lombard Queen), the names of Felicitas and six of her martyred sons occur.

In the “Pittacia” or labels they are grouped topographically together, as we have given them above, Felicitas’ being in a separate label, Januarius also in a separate label, then the two groups together as above, the “two” and the “three.” There is a reason for S. Silanus, who was buried with his mother in the cemetery named after her, being absent from this “Monza” Catalogue, and from the labels on the phials of oil. His body, as the “Liberian” Catalogue informs us, was missing for a season from its original loculus, it having been stolen away, but was subsequently recovered and replaced.

The suspicion of the legendary character of the story of the martyrdom of S. Felicitas and her seven sons is largely traceable to the conclusions of some critical scholars (by no means of all) that the “Acts of S. Felicitas” and her sons are not authentic, that is, that they are not a contem