BOOK V

THE JEW AND THE TALMUD

INTRODUCTORY

Among all the various evidential arguments adduced in support of the truth of Christianity, many of them of a most weighty character and capable of an almost indefinite expansion, the history of the Jewish people, their wonderful past and their present condition, their numbers, their books, their ever-growing influence in the world of the twentieth century, must be considered as the most striking and remarkable.

The Christianity of the first century was surely no new religion; it was closely knit to, bound up with, the great Hebrew tradition. The sacred Hebrew tradition was the first chapter—the preface, so to speak—of the Christian revelation.

The early or pre-Christian details of the Jewish story are well known and generally accepted. The Old Testament account of the Jewish race historically is rarely disputed.

Less known and comparatively little regarded is the subsequent history of the Chosen People; over the records of their fate, after the final and complete separation of Judaism and Christianity, an almost impenetrable mist settled, and the story of the fortunes of the remnant of the Jews who survived the terrible exterminating wars of Titus and Hadrian has been generally neglected by the historians of the great Empire.

Very few have even cared to ask what happened to that poor remnant of vanquished Jews: all that is commonly known is that a certain number survived the great catastrophes, and that their scattered descendants, in different lands, appear and reappear all through the Middle Ages—a wandering and despised folk, generally hated and hating.

But these are still with us, and among us; that they occupy in our day and time a peculiar, a unique position of power and influence which they have gradually acquired in all grades of modern society in many lands is now universally recognized.

This subsequent history of the fortunes of the Jewish people from the dates of their final separation from the Christian community, and the great catastrophes of the years of grace A.D. 70 and A.D. 135, constitutes a piece of supreme importance in the evidential history of the religion of Jesus; and yet, strange to say, it is, comparatively speaking, unknown and neglected.

It will be seen, as the pages of this wonderful story are turned over, how the guiding hand of the Lord, though in a different way, just as in the far-back days of the desert wanderings, has been ever visible in all the strange sad fortunes of the people, once the beloved of God.

The Jews of the twentieth century, numbering perhaps some ten or eleven millions, although scattered over many lands, constitute a distinct race, a separate people or nation. While during the Christian centuries all other races—peoples—nations—without a single exception have become extinct, or have become fused and merged with other and newer races and peoples, they, the Jews, have alone preserved their ancient nationality, their descent, their peculiar features, their individuality, their cherished traditions—absolutely intact.

It does not seem ever to have been remarked that the rise and influence of the great Rabbinic schools of Palestine and Babylonia, at Tiberias and Jamnia, at Sura and Pumbeditha—schools devoted to the study of the Torah (the Law) and the other books of the Old Testament, were coincident with the rise and influence of the Gnostic schools, schools in which the Old Testament was generally reviled and discredited. Is it too much to assume that echoes from the great Rabbinic teaching centres reached and sensibly influenced the Christian masters in their life and death contest with Gnosticism, a contest in which the Old Testament, its divine origin and its authority, was ever one of the principal questions at stake?

Nor is it an altogether baseless conception which sees that the reverence and love of at least a large proportion of earnest Christian folk for the Old Testament books, a reverence and a love that for more than eighteen hundred years has undergone no diminution or change, are in large measure due to the reverential handling, to the patient tireless studies of the great Rabbinical schools of the early Christian centuries—to the passionate, possibly exaggerated, love of the Jew for his precious book.

Though men guess it not, surely echoes from those strange Jewish schools of Tiberias and Sura, whose story we are about to relate, have reached the hearts of unnumbered Christians to whom the Jewish schools in question and their restless toil, all centering in the Holy Books in question, are but the shadow of a name?

I

THE HISTORY OF THE THREE WARS WHICH CLOSED THE CAREER OF JUDAISM AS A NATION

In the wonderful Jewish epic—so closely united to the Christian story—which stretches already over several thousand years, the history of the three last awful wars which led to their extinction as a nation, though not as a people, is merely a terrible episode in the many-coloured records of the wonderful race.

But these wars are specially important, for they were the earthly cause of the great change which passed over the fortunes of the Jews. Since the last of the three wars they have ceased to be a separate nation, and have become a wandering tribe scattered over the earth; but though wanderers, they are now more numerous, more influential in the world, than they had ever been even in the days of their greatest grandeur and magnificence.

The curious religious mania which seems to have possessed them, and which led them to revolt against the far-reaching power of the Roman Empire, is in some respects a mystery. We can only very briefly recount here the state of parties in Jerusalem, the centre of the nation, for a few years before the revolt which led to the first great war.

In the year B.C. 63 the Roman commander Pompey established the Roman rule over Judæa; from B.C. 6 the Jewish province, still preserving a partial independence, was governed by procurators sent from Rome, and by a native Herodian dynasty. The Palestinian Jews were roughly made up in this period of three parties:

(1) The Sadducees and Herodians, who occupied most of the high offices and the priesthood.

(2) The Pharisees. Strict Jews, loving with a devoted love the Torah or Mosaic Law; on the whole not favourable to the Roman and Herodian rule, but generally quiet and peace-loving. These included dreamers—men quietly longing for the promised Messiah, Essenes, and later, towards the end of the period we are speaking of, Christian Jews.

(3) Zealots—including adventurers, the Sicarii (or assassins), a wild turbulent clique (or sect), and a confused medley of disorderly folk, making up a formidable party of enthusiasts, expecting the early advent of a Messiah who should restore the past glories of the Jewish race; these were usually fierce revolutionaries, intensely dissatisfied with the state of things then prevailing; hating Rome and the Herodian dynasty favoured by Rome with a fierce hatred.

These Zealots had a very large, though disorderly, following among the people.

In A.D. 66 the revolt broke out in the Holy City. Florus, the Roman Procurator (or Governor), whose conduct during the early stages of the great revolt is inexplicable, left the city, leaving behind him only a small garrison; the revolt spread not only in Palestine and in parts of the neighbouring province of Syria, but far beyond—notably in the great city of Alexandria, where a large Jewish colony dwelt. Scenes of terrible violence were common, and fearful massacres are recorded to have taken place in various centres of population where Jews were numerous; the revolt became serious, and the Imperial Legate of Syria, Cestius Gallus, took the field against the insurgents. He seems to have been a thoroughly incompetent commander, and failed completely in his efforts to regain possession of Jerusalem, the headquarters of the revolutionary party. Gallus retreated, suffering great loss. The failure of Gallus inflicted a heavy blow upon Roman prestige.

To put an end to the serious and widespread revolt, in the year of grace 67 Vespasian, one of the ablest and most distinguished of the Roman generals, was appointed to the supreme command in Syria.

Gradually, as the result of a terrible campaign, Vespasian restored quiet in Palestine and the neighbouring region, and laid siege to the Holy City, where the Zealots had established what can only be termed a reign of terror.

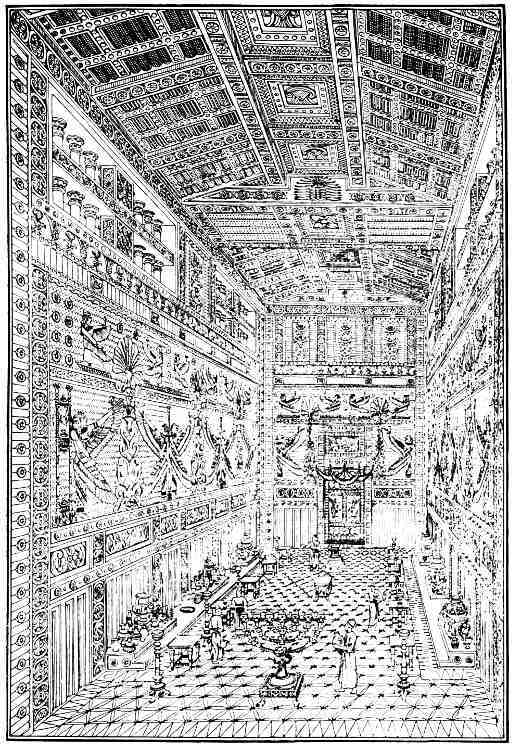

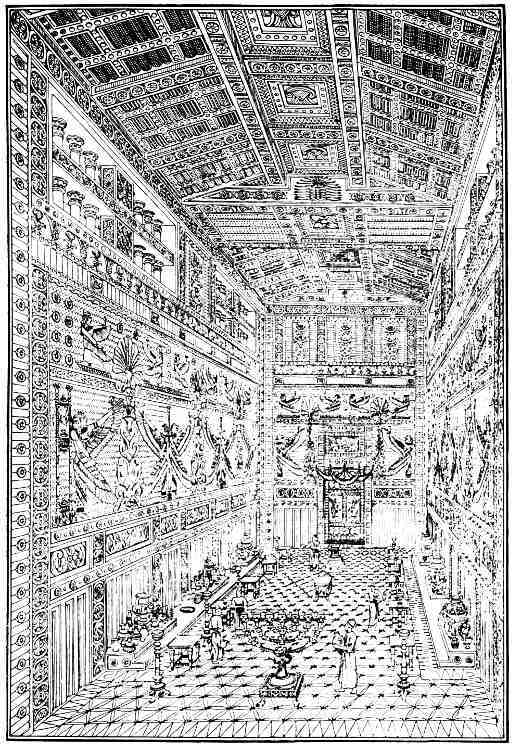

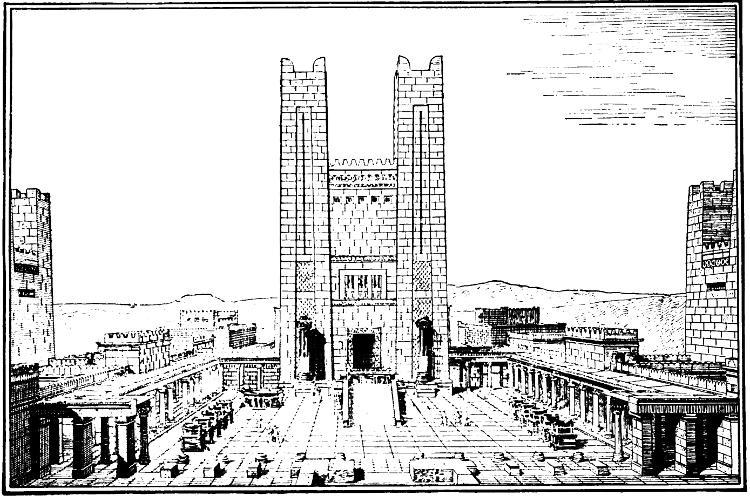

THE TEMPLE, JERUSALEM—THE HOLY PLACE BEFORE ITS DESTRUCTION BY TITUS, A.D. 70

In the following year, A.D. 68, the violent death of the Emperor Nero, and the state of confusion that followed his death throughout the Empire, determined Vespasian to pause in his operations, and for a short period Jerusalem was left in the hands of the Zealots. The brief reigns of the Emperors Galba, Otho, and Vitellius were followed by the sudden election of Vespasian to the Empire in the year 69, the electors being for the most part his own devoted and disciplined legions in Syria.

Vespasian soon after his election returned to Rome, and the Empire, now under his strong rule, was once more united and quiet. He left behind him in Palestine as supreme commander his eldest son Titus, a general of great power and ability.

The siege of the revolted Jerusalem was once more pressed on; an iron circle now encircled the doomed city, which, in addition to its wonderful memories of an historic past, was one of the strong fortresses of the world.

The history of the siege and the eventual fall and ruin of the famous Jewish capital, with all its nameless horrors, has been often told and retold; but the sad episode of the burning of the Temple, with all its eventful consequences, must be briefly touched on.

Why was this world-famous sanctuary—then standing in all its marvellous beauty, with its matchless treasures, some of them environed with an aureole of sanctity simply unequalled in the story of the nations in the sphere of Roman influence—ruthlessly destroyed, and its wondrous treasures swept out? This was not the usual policy of far-seeing Rome.

According to Josephus, the burning of the Temple was the result of accident, and was not owing to any premeditated plan or order issuing from the Roman commander-in-chief.

Modern scholars,[145] however, believe that a passage from the lost Histories of Tacitus has been discovered which describes how a council of war was held by Titus after the capture of Jerusalem in which it was decided that the Temple ought to be destroyed, in order that the religion of the Jews and of the Christians might be more completely stamped out.

In the Talmud[146] the burning of the Temple is ascribed to the “impious Titus.”

The cruelties which are associated with the storming of Jerusalem—the loss of life and the subsequent fate of the prisoners captured by the victorious army of Titus—make up a tale of horror which perhaps is unequalled in the world’s history; there is, however, no doubt that the awful scenes of carnage and the fate of the defenders who survived the fall of the city were in large measure owing to the obstinate defence and irreconcilable hatred of the party of Jewish Zealots who provoked the war and for so long a time had been masters in the hapless city.

The result of the siege by Titus may be briefly summed up as follows. The Temple and the City of Jerusalem were absolutely razed to the ground, and may be said to have completely disappeared; only the mighty foundations of the magnificent Temple remained. These still are with us, and after nearly two thousand years bear their silent witness to the vastness and extent of the third Temple. It is no exaggeration which describes it as one of the most magnificent buildings of the Old World.

For some fifty-two years—that is, from A.D. 70 to A.D. 122—a vast heap of shapeless ruins was all that remained of the historic City of the Jews and its splendid Temple. In one corner of the ruins during this period of utter desolation the Tenth Legion (Fretensis) kept watch and ward over the pathetic scene of ruin.

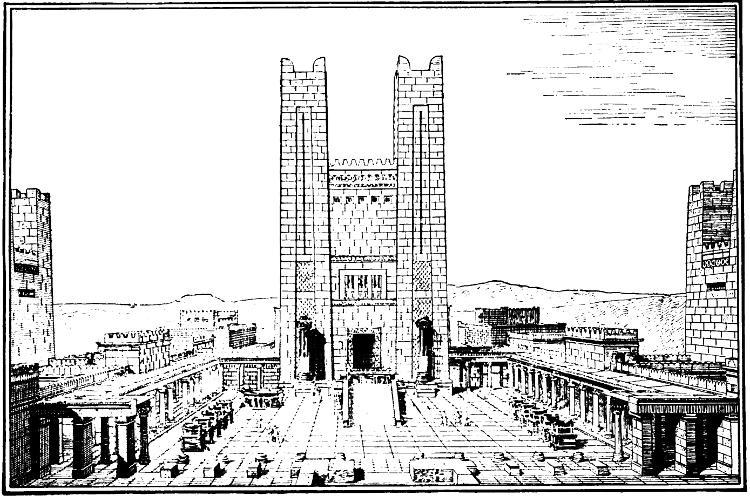

In the year of grace 122, under the orders of the Emperor Hadrian, a new pagan city, known as Ælia Capitolina, slowly began to arise on the ancient site. This new city will be briefly described in due course.

The year following the awful catastrophe which befel the Jewish nation witnessed one of the most remarkable of the long series of “triumphs” which usually marked the close of the successful Roman wars.

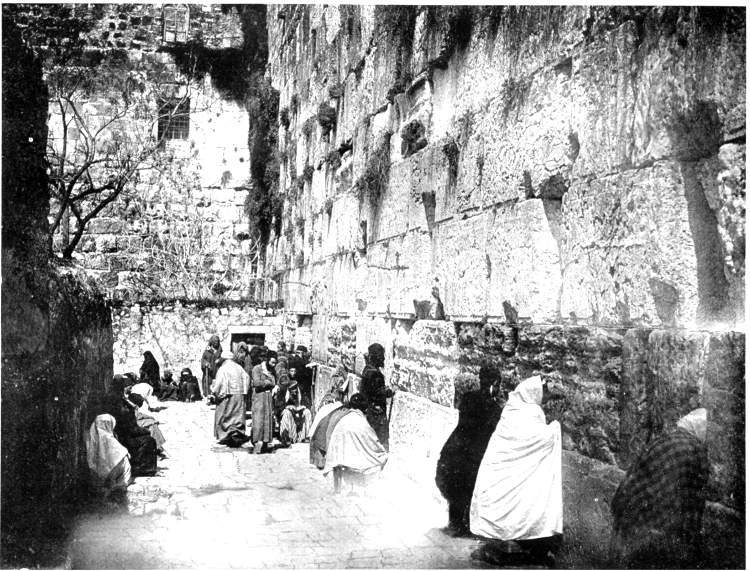

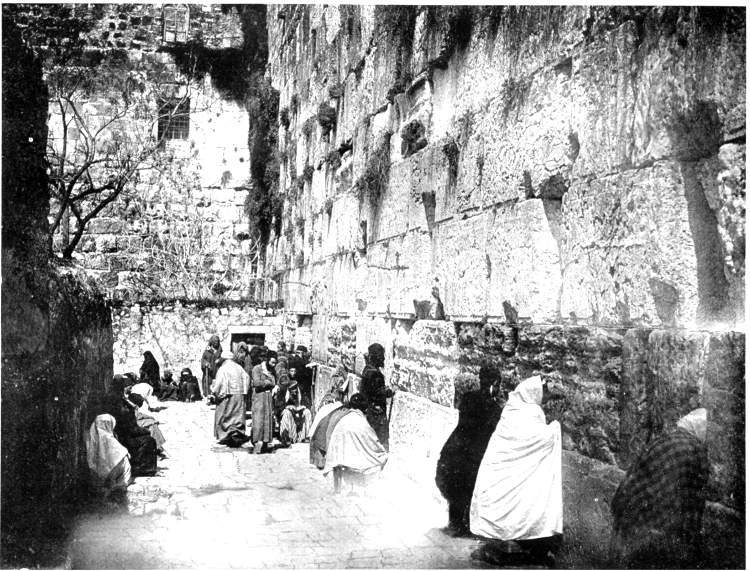

THE “WAILING-PLACE” OF THE JEWS BEFORE THE RUINED WALLS OF THE TEMPLE

In A.D. 71, Titus, with his father Vespasian and brother Domitian, with extraordinary pomp and a carefully arranged pictorial display, entered Rome. This triumph was adorned with a long train of captive Jews, some of whom were publicly put to death as part of the great show. Among the more precious spoils of the fallen city were conspicuously displayed some of the celebrated objects rescued by the victors out of the burning Temple,—such as the famous seven-branched sacred candlestick; the golden table of shewbread; the purple veil which hung before the Holy of Holies; and the precious Temple copy of the Torah—the sacred Law of Moses.

The story of the great triumph is still with us, graved upon the marble of the slowly crumbling Arch of Titus,—the traveller may still gaze upon the figure of the great general, crowned by Victory, in his triumphal car driven by the goddess Rome, and upon the same imperial figure borne to heaven[147] by an eagle. Still the carved representation of the sacred candlestick of the seven branches, and the golden table, are beheld by the Christian with mute awe; by the Jew with a mourning that refuses to be comforted. But the sacred things[148] themselves over which brood such ineffable memories are gone.

The fall of Jerusalem, the utter destruction of the Holy City, the burning of the Temple, really sealed the fate of the Jews as a separate nation. The centre of the chosen race existed no longer. The sacred rites, the daily sacrifice, and the offering ceased for ever. The great change in Judaism we are going to dwell upon must be dated from the year 70. But more terrible events had yet to happen before the Jew acknowledged his utter defeat, and recognized that a great change had passed over him and had finally altered the scene of his cherished hopes and glorious anticipations.

Two more bloody wars had to be fought out before the Jew settled down to his new life—the life to be lived by the Chosen People for a long series of centuries, the life he is living still, though more than 1800 years have come and gone since Titus brought the sacred Temple treasures from the ruined city to grace the proud Roman triumph.

Under Trajan in A.D. 116–7, and again under Hadrian in A.D. 133–4, the Zealot party of the defeated but still untamed people again rose up in arms against the mighty Empire in the heart of which they dwelt.

We will rapidly sketch these last disastrous revolts. The spirit of unrest and of hatred of the Roman power—the wild Messianic hopes which had inspired the party of Zealots in Jerusalem in the first war which had ended so disastrously—still lived in the great Jewish centres of population outside the Holy Land, in countries where the desolation which succeeded the events in 70 had not been acutely felt.

The Palestinian Jews for a time were apparently hopelessly crushed, but the Jews of Cyrene and Alexandria were still a powerful and dangerous group. It is impossible now to indicate the precise causes of the formidable rising of A.D. 116–7. The absence of Trajan and his great army in the more distant regions of Asia, and the news that the Roman arms had met with a serious check in that distant and dangerous campaign, seem to have given the signal for an almost simultaneous Jewish uprising in the Cyrene province, in the city of Alexandria, and in Cyprus.

We do not possess any very exact details here. The revolt was generally characterized by horrible cruelties on the part of the Jewish insurgents, and we read of fearful massacres perpetrated by the revolted Jews. The insurrection spread with alarming rapidity, and became a grave danger to the Empire. At first we only hear of several successes and victories. In the cities of Alexandria and Cyrene a reign of terror prevailed; but, as was ever the case when Rome in good earnest put forth her disciplined forces, the insurgents found themselves outnumbered and out-generalled. Two of the most distinguished of the imperial commanders, Marcius Turbo and Lucius Quietus, conducted the military operations. The war—for the Jewish revolt of A.D. 116–7 assumed the proportions of a grave war—lasted well-nigh two years; but the insurgents were in the end completely routed.

The numbers of slain in this wild and undisciplined outburst of Jewish fury, according to the records of the historians of the war, are so great that we are tempted to suspect them exaggerated. In Cyrene and the neighbouring districts the number who perished is given as twenty-two thousand; the loss of life in Alexandria, Egypt, and Cyprus seems to have been equally terrible. But even granted that the numbers of Jews who perished in this fanatical rebellion have been, from one cause or other, exaggerated, it is certain that the numbers of the slain were enormous, that the power and influence of the Chosen People suffered a terrible check as the result of this rising, and that in the great cities of Cyrene and Alexandria the Jewish population of these centres—large and flourishing communities, possessing great wealth and influence, distinguished for their high culture and learning—were almost annihilated. The results of the insane revolts of A.D. 116–7 were indeed disastrous to the fortunes of this extraordinary and wonderful people.

But the end was not yet. Another bloody war, with all its fearful consequences, had to be waged between the Jew and the Empire before the Chosen People finally resigned itself to the new life it was destined to live through the long centuries which followed. The old spirit of restlessness, of wild visionary hopes of some great one who should arise in their midst, still lived among the more ardent and fervid members of the now scattered and diminished people.

The exciting causes of the last great revolt have been variously stated. It is probable that the conduct of Hadrian in his latter years had become less tolerant, while a persecuting spirit more or less prevailed in his government. Among other irritating measures devised by Rome, the ancient rite of circumcision apparently was forbidden. But the immediate cause of the Jewish uprising no doubt was the steady progress made in the building of the new city, Ælia Capitolina, on the site of Jerusalem and the Temple.

That a pagan city, with its theatres, its baths, its statues, should replace the old home of David and Solomon; that a Temple of Jupiter should be built on the site of the glorious House of the Eternal of Hosts; that the very stones of old Jerusalem and her adored sanctuary should be used for the construction of the new city of idols—was indeed especially hateful to the proud and fanatic Jew. Sacrilege could go no further. Rapidly the insurrection which began in Southern Judæa spread. Once more the Holy Land, especially in the southern districts, became the scene of a fierce religious war; Bethia, a fortress some fifteen miles from Jerusalem, became the central place of arms of the fierce insurgents, but the revolt spread far beyond the districts of Palestine.

In one striking particular this third Jewish war differed from the first and second revolts. In the earlier uprisings it was the hope of the appearance of a conquering Messiah which inspired the fanatical insurgents. In the third revolt a false Messiah actually presented himself, and gave a new colour and spirit to this dangerous insurrection.

The hero of the war—the pseudo-Messiah known as Bar-cochab (the son of a Star)—is a mysterious person; his name appears to have been a play upon his real appellation, and was assumed by him as representing the Star pictured in the famous prophecy of Balaam (Num. xxiv. 17): “I shall see him,” said the seer of Israel, “but not now.... There shall come a Star out of Jacob, and a Sceptre shall rise out of Israel.” Was this pseudo-Messiah simply an impostor, a charlatan, or did he really believe in his mission? The Talmud generally execrates his memory, but the principal doctor of that age, Rabbi Akiba, at a time when the Doctors of the Law had begun to exercise a paramount influence among the Jewish people, believed in him with an intense belief, and supported him in his Messianic pretensions.

Many, but by no means all, of the great Rabbis of the day seem to have supported this Bar-cochab, and the Talmud tells us that not a few of them endured martyrdom at the hands of the victorious Roman government. All contemporary history of this war is, however, confused,—the Talmud notices are especially so; the details are simply impossible to grasp.

Of the bravery of Bar-cochab there is no doubt; he perished before the end of the war, and some time after Rabbi Akiba, his most influential supporter, was put to an agonizing death by the victors.

Of Rabbi Akiba’s sincerity there are abundant proofs. His memory was ever held in the highest honour by his countrymen. He was reputed to be the most learned and eloquent of that famous generation of Jewish teachers. The strange mistake he made in recognizing the false Messiah Bar-cochab is hard to account for.

As in the case of the two first famous Jewish wars, the Roman power seems at first to have underrated this rebellion, which, however, soon assumed a most formidable character. The general commanding in the Syrian provinces proving incapable, the ablest of the imperial generals, Sextus Julius Severus, was summoned from his command in distant Britain to Judæa. The Roman tactics employed were generally similar to those adopted by Trajan’s generals in the second Jewish war of A.D. 116–7. Severus avoided any so-called pitched battle, but advanced gradually, attacking and besieging each of the rebel garrisons, thus gradually wearing out the impetuosity and ardour of the fanatical insurgents. The war lasted from two to three years. The devastation, the result of this war, was evidently very awful, and the numbers of the slain seem to have been enormous. We read of 50 armed places being stormed, 985 villages and towns being destroyed; 580,000 men were said to have been slain, besides many who perished through hunger and disease: the numbers of slain in another account are, however, only given as amounting to 180,000. One cannot help coming to the conclusion that all these numbers are considerably exaggerated. Judæa, however, there is no doubt, especially in the southern districts, became literally a desert; wolves and hyenas are stated to have roamed at pleasure over the ravaged country; the south of Palestine became a vast charnel-house, and the present barren appearance of the country indicates that some terrible catastrophe has at some distant period passed over the land.[149]

The sternest measures effectually to stamp out all traces of revolt on the part of the Jewish nation were adopted by the Roman government after the close of the campaign. Numbers of the fugitives were ruthlessly put to death. Many were sold into slavery. No Jew was ever allowed to approach the ruins of the Holy City. Once in the year, on “the day of weeping,” such of the hapless race who chose were suffered to come and mourn for a brief hour over the shapeless pile of stones which once had been a portion of their sacred Temple.

For a time a bitter persecution throughout the Empire punished this last formidable uprising; but these rigorous measures were very soon relaxed when all fear of another outbreak had passed away, and the Jews, or what remained of the people, were suffered to live as they pleased, to worship after their own fashion, and to pursue the study of their loved Law unmolested.

M. de Champagny (Les Antonins, livre iii. chap, iii.) estimates the number of Jews who perished in the three great wars of A.D. 70, of A.D. 116–7, and of A.D. 132–3–4 roughly as follows: Under Titus, about two millions; under Trajan, about two hundred thousand; under Hadrian, about one million.[150]

The third war was termed in the Babylonian Talmud “the War of Extermination.”

II

(a) RABBINISM

We have described the three fatal wars at some length, because the wonderful history of the Jewish race entered upon an entirely new phase after the disastrous termination of the third of these terrible revolts. From the year of our Lord 134–5 they ceased to be a nation and became wanderers over the earth.

Yet in numbers and influence they can scarcely be said to have diminished. They amalgamated with no nation; they remained a marked and separate people, and so they continue to this day, though well-nigh eighteen long and troubled centuries have passed since the great ruin.

To what earthly cause is this marvellous preservation of the Jews to be attributed? Unhesitatingly we reply, Not to the rise of Rabbinism,—it had long existed among the Chosen People,—but to the development and consolidation of Rabbinism and to the famous outcome of Rabbinism, the Talmud.

The traditional history of Rabbinism and the beginning of the marvellous Rabbinic book, the Talmud, is given in the Mishnah treatise “Pirke Aboth” (Sayings of the Fathers). It is as follows:—

Moses received the written Law (the Torah) on Mount Sinai. He also received from the Eternal a further Law, illustrative of the written Law. This second Law was known as the “Law upon the lip.” This was never committed to writing, but was handed down from generation to generation. Moses committed this oral Law to Joshua; Joshua committed it to the Elders; the Elders committed it to the Prophets; the Prophets handed on the sacred tradition of “the Words of the Eternal” to the Men of the Great Synagogue. These last are regarded as the fathers of “Rabbinism.” Maimonides tells us that these fathers of “Rabbinism” succeeded each other (to the number of 120), commencing with the prophet Haggai, B.C. 520, who in the Talmud is described as the Expounder of the oral Law. The last member of the “Great Synagogue” was Simon the Just, circa B.C. 301.

After Simon the Just a succession of eminent teachers known as the “Couples” handed down the sacred traditions of the “Law upon the lip” to the time of Hillel and Shammai, when we approach to the Christian era. Hillel, according to the Talmudic tradition, is said to have lived 100 years before the destruction of Jerusalem, A.D. 70, and thus to have been a contemporary of Herod the Great.

Very little really is known of the “Men of the Great Synagogue,” or of the ten “Couples” who succeeded them; little more than their names has been preserved. It is scarcely probable that in each generation only a pair of specially distinguished scholars should have lived. Most likely just ten names were known, and they were formed into five pairs or couples of contemporaries, after the fashion of the last and most famous pair, Hillel and Shammai. But from the times of Hillel and Shammai we have abundant historical testimony as to the existence and labours of the Rabbinic schools. Well-nigh all that we have related in the above passage is purely traditionary. There is no doubt a basis of truth in the account we have given, but the contemporary history is too scanty for us to describe this relation in the treatise “Pirke Aboth,” which thus connects the Mishnah compilation in a direct chain with Moses, as anything more than a widely circulated legendary and traditional story.

We can, however, certainly assert that the foundations of the teaching of the school of Rabbinism which, after the great ruin of the year of Grace 70, began to exercise a paramount influence over the fortunes of the Jewish race, were laid at a very early period, several hundred years before the Christian era.

There is no doubt that Hillel and Shammai founded or, more accurately speaking, developed the existing Rabbinic schools and gathered into them large numbers of disciples. The great development of Rabbinism which is ascribed to the two famous teachers Hillel and Shammai was evidently owing to the complete absorption of Palestine by Rome, under the baleful influence of the royalty of Herod the Great; these causes were gradually undermining Judaism, not only in a political but also in its religious aspect. Hillel and Shammai were fervid and earnest Jews, and were determined to infuse a new religious spirit into the nation. Still, it is more than probable that all this early Rabbinism would scarcely have been more than a school of curious literary speculation, and perhaps would not have seriously and permanently influenced the life of the Jewish people, had it not been for the awful events of the year A.D. 70. When Jerusalem ceased to exist, and the Temple was finally destroyed, then Christianity emerged from the heart of Judaism, and gathered into its fold many of the Chosen People.

THE TEMPLE, JERUSALEM,