CHAPTER XV

A volume might well be written on what I must compress into this chapter. On the narrow canvas of these few pages must be outlined the crowded incidents of that noble fight above Crecy, whereof your historians know but half the truth, and these same lines, charged with the note of victory, full of the joyful exultation of the mêlée and dear delight of hard-fought combat—these lines must, too, record my own illimitable grief.

If while I write you should hear through my poor words aught of the loud sound of conflict, if you catch aught of the meeting of two great hosts led on by kingly captains, if the proud neighing of the war-steeds meet you through these heavy lines and you discern aught of the thunder of charging squadrons, aught of the singing wind that plays above a sea of waving plumes as the chivalry of two great nations rush, like meeting waves, upon each other, so shall you hear, amid all that joyful tumult, one other sound, one piercing shriek, wherefrom not endless scores of seasons have cleared my ears.

Listen, then, to the humming bow-strings on the Crecy slopes—to the stinging hiss of the black rain of English arrows that kept those heights inviolable—to the rattle of unnumbered spears, breaking like dry November reeds under the wild hog’s charging feet, as rank behind rank of English gentlemen rush on the foe! Listen, I say, with me to the thunderous roar of France’s baffled host, wrecked by its own mightiness on the sharp edge of English valor, listen to the wild scream of hireling fear as Doria’s crossbowmen see the English pikes sweep down upon them; listen to the thunder of proud Alençon sweeping round our lines with every glittering peer in France behind him, himself in gemmy armor—a delusive star of victory, riding, revengeful, on the foremost crest of that wide, sparkling tide! Hear, if you can, all this, and where my powers fail, lend me the help of your bold English fancy.

It was a hard-fought day indeed! Hotly pursued by the French King, numbering ourselves scarce thirty thousand men, while those behind us were four times as many, we had fallen back down the green banks of the Somme, seeking in vain for a ford by which we might pass to the farther shore. On this morning of which I write so near was Philip and his vast array that our rearguard, as we retreated slowly toward the north, saw the sheen of the spear-tops and the color on whole fields of banners, scarce a mile behind us. And every soldier knew that, unless we would fight at disadvantage, with the river at our backs, we must cross it before the sun was above our heads. Swiftly our prickers scoured up and down the banks, and many a strong yeoman waded out, only to find the hostile water broad and deep; and thus, all that morning, with the blare of Philip’s trumpets in our ears, we hunted about for a passage and could not find it, the while the great glittering host came closing up upon us like a mighty crescent stormcloud—a vast somber shadow, limned and edged with golden gleams.

At noon we halted in a hollow, and the King’s dark face was as stern as stern could be. And first he turned and scowled like a lion at bay upon the oncoming Frenchmen, and then upon the broad tidal flood that shut us in that trap. Even the young Prince at his right side scarce knew what to say; while the clustering nobles stroked their beards and frowned, and looked now upon the King and now upon the water. The archers sat in idle groups down by the willows, and the scouts stood idle on the hills. Truth, ’twas a pause such as no soldier likes, but when it was at the worst in came two men-at-arms dragging along a reluctant peasant between them. They hauled him to the Sovereign, and then it was:

“Please your Mightiness, but this fellow knows a ford, and for a handful of silver says he’ll tell it.”

“A handful of silver!” laughed the joyful King. “God! let him show us a place where we can cross, and we will smother him with silver! On, good fellow!—the ford! the ford! and come to us to-morrow morning and you shall find him who has been friend to England may laugh henceforth at sulky Fortune!”

Away we went down the sunburnt, grassy slopes, and ere the sun had gone a hand-breadth to the west of his meridian a little hamlet came in sight upon the farther shore, and, behind it a mile, pleasant ridges trending up to woods and trees. Down by the hamlet the river ran loose and wide, and the ebbing stream (for it was near the sea) had just then laid bare the new-wet, shingly flats, and as we looked upon them, with a shout that went from line to line, we recognized deliverance. So swift had been our coming that when the first dancing English plumes shone on the August hill-tops the women were still out washing clothes upon the stones, and when the English bowmen, all in King Edward’s livery, came brushing through the copses, the kine were standing knee-deep about the shallows, and the little urchins, with noise and frolic, were bathing in the stream that presently ran deep and red with blood. And small maids were weaving chaplets among those meadows where kings and princes soon lay dying, and tumbling in their play about the sunny meads, little wotting of the crop their fields would bear by evening, or the stern harvest to be reaped from them before the moon got up.

We crossed; but an army does not cross like one, and before our rearward troops were over the French vanguard was on the hill-tops we had just quitted, while the tide was flowing in strong again from the outer sea.

“Now, God be praised for this!” said King Edward, as he sat his charger and saw the strong salt water come gushing in as the last man toiled through. “The kind heavens smile upon our arms—see! they have given us a breathing space! You, good Sir Andrew Kirkaby, who live by pleasant Sherwood, with a thousand archers stand here among the willow bushes and keep the ford for those few minutes till it will remain. Then, while Philip watches the gentle sea fill up this famous channel, and waits, as he must wait, upon his opportunity, we will inland, and on yonder hill, by the grace of God and sweet St. George, we will lay a supper-place for him and his!”

So spoke the bold King, and turned his war-horse, and, with all his troops—seeming wondrous few by comparison of the dusky swarms gathering behind us—rode north four hundred yards from Crecy. He pitched upon a gentle ridge sloping down to a little brook, while at top was woody cover for the baggage train, and near by, on the right, a corn-mill on a swell. ’Twas from that granary floor, sitting stern and watchful, his sword upon his knees, his impatient charger armed and ready at the door below, that the King sat and watched the long battle.

Meanwhile, we strengthened the slopes. We dug a trench along the front and sides, and, with the glitter of the close foeman’s steel in our eyes, lopped the Crecy thickets. And, working in silence (while the Frenchman’s song and laughter came to us on the breeze), set the palisades, and bound them close as a strong fence against charging squadrons, and piled our spears where they were handy, and put out the archers’ arrows in goodly heaps. Jove! we worked as though each man’s life depended on it, the Prince among us, sweating at spade and axe, and then—it was near four o’clock on that August afternoon—a hush fell upon both hosts, and we lay about and only spoke in whispers. And you could hear the kine lowing in the valley a mile beyond, and the lapwing calling from the new-shorn stubble, and the whimbrels on the hill-tops, and the river fast emptying once again, now prattling to the distant sea. ’Twas a strange pause, a sullen, heavy silence, no longer than a score of minutes. And then, all in a second, a little page in the yellow fern in front of me leaped to his feet, and, screaming in shrill treble that scared the feeding linnets from the brambles, tossed his velvet cap upon the wind and cried:

“They come! they come, St. George! St. George for merry England!”

And up we all sprang to our feet, and, while the proud shout of defiance ran thundering from end to end of our triple lines, a wondrous sight unfolded before us. The vast array of France, stretching far to right and left and far behind, was loosed from its roots, and coming on down the slope—a mighty frowning avalanche—upon us, a flowing, angry sea, wave behind wave, of chief and mercenary—countless lines of spear and bowmen and endless ranks of men-at-arms behind—an overwhelming flood that hid the country as it marched shot with the lurid gleam of light upon its billows, and crested with the fluttering of endless flags that crowned each of those long lines of cheering foemen.

That tawny fringe there in front a furlong deep and driven on by the host behind like the yellow running spume upon the lip of a flowing tide was Genoese crossbowmen, selling their mean carcasses to manure the good Picardy soil for hireling pay. Far on the left rode the grim Doria, laughing to see the little band set out to meet his serried vassals, and, on the right, Grimaldi’s olive face scowled hatred and malice at the hill where the English lay.

There, behind these tawny mercenaries in endless waves of steel, D’Alençon rode, waving his princely baton, and marshaled as he came rank upon rank of glittering chivalry—a fuming, foamy sea of spears and helmets that flashed and glittered in the sun, and tossed and chafed, impatient of ignoble hesitance, and flowed in stately pride toward us, the white foam-streaks of twenty thousand plumed horsemen showing like breakers on a shallow sea, as that great force, to the blare of trumpets, swept down.

And, as though all these were not enough to smother our desperate valor even with the shadow of their numbers, behind the French chivalry again advanced a winding forest of spearmen stooping to the lie of the ground, and now rising and now falling like water-reeds when the west wind plays among them. Under that innumerable host, that stretched in dust and turmoil two long miles back to where the gray spires of Abbeville were misty on the sky, the rasp of countless feet sounded in the still air like the rain falling on a leafy forest.

Never did such a horde set out before to crush a desperate band of raiders. And, that all the warlike show might not lack its head and consummation, between their rearguard ranks came Philip, the vassal monarch who held the mighty fiefs that Edward coveted. Lord! how he and his did shine and glint in the sunshine! How their flags did flutter and their heralds blow as the resplendent group—a deep, strong ring of peers and princes curveting in the flickering shade of a score of mighty blazons—came over the hill crest and rode out to the foremost line of battle and took places there to see the English lion flayed. With a mighty shout—a portentous roar from rear to front which thundered along their van and died away among the host behind—the French heralded the entry of their King upon the field, and, with one fatal accord, the whole vast baying pack broke loose from order and restraint and came at us.

We stood aghast to see them. Fools! Madmen! They swept down to the river—a hundred thousand horse and footmen bent upon one narrow passage—and rushed in, every chief and captain scrambling with his neighbor to be first—troops, squadrons, ranks, all lost in one seething crowd—disordered, unwarlike. And thus—quivering and chaotic, heaving with the stress of its own vast bulk—under a hundred jealous leaders, the great army rushed upon us.

While they struggled thus, out galloped King Edward to our front, bareheaded, his jeweled warden staff held in his mailed fist, and, riding down our ranks, and checking the wanton fire of that gray charger, which curveted and proudly bent his glossy neck in answer to our cheering, proud, calm-eyed, and happy, King Edward spoke:

“My dear comrades and lieges linked with me in this adventure—you, my gallant English peers, whose shiny bucklers are the bright bulwarks of our throne, whose bold spirits and matchless constancy have made this just quarrel possible—oh! well I know I need not urge you to that valor which is your native breath. Right well I know how true your hearts do beat under their steely panoply; and there is false Philip watching you, and here am I! Yonder, behind us, the gray sea lies, and if we fall or fail it will be no broader for them than ’tis for us. Stand firm to-day, then, dear friends and cousins! Remember, every blow that’s struck is struck for England, every foot you give of this fair hillside presages the giving of an ell of England. Remember, Philip’s hungry hordes, like ragged lurchers in the slip, are lean with waiting for your patrimonies. Remember all this, and stand as strong to-day for me as I and mine shall stand for you. And you, my trusty English yeomen,” said the soldier King—“you whose strong limbs were grown in pleasant England—oh! show me here the mettle of those same pastures! God! when I do turn from yonder hireling sea of shiny steel and mark how square your sturdy valor stands unto it—how your clear English eyes do look unfaltering into that yeasty flood of treachery—why, I would not one single braggart yonder the less for you to lop and drive; I would not have that broad butt that Philip sets for us to shoot at the narrower by one single coward tunic! Yonder, I say, ride the lank, lusty Frenchmen who thirst to reeve your acres and father to-morrow, if so they may, your waiting wives and children. To it, then, dear comrades—upon them, for King Edward and for fair England’s honor! Strike home upon these braggart bullies who would heir the lion’s den even while the lion lives; strike for St. George and England! And may God judge now ’tween them and us!”

As the King finished, five thousand English archers went forward in a long gray line, and, getting into shot of the first ranks of the enemy, drew out their long bows from their cowhide cases and set the bow-feet to the ground and bent and strung them; and then it would have done you good to see the glint of the sunshine on the hail of arrows that swept the hillside and plunged into those seething ranks below. The close-massed foemen writhed and winced under that remorseless storm. The Genoese in front halted and slung their crossbows, and fired whole sheaves of bolts upon us, that fell as stingless as reed javelins on a village green, for a passing rainstorm had wet their bowstrings and the slack sinews scarce sent a bolt inside our fences, while every shaft we sped plunged deep and fatal. Loud laughed the English archers at this, and plied their biting flights of arrows with fierce energy; and, all in wild confusion, the mercenaries yelled and screamed and pulled their ineffectual weapons, and, stern shut off from advance by the flying rain of good gray shafts, and crushed from behind by the crowding throng, tossed in wild confusion, and broke and fled.

Then did I see a sight to spoil a soldier’s dreams. As the coward bowmen fell back, the men-at-arms behind them, wroth to be so long shut off the foe, and pressed in turn by the troops in rear, fell on them, and there, under our eyes, we saw the first rank of Philip’s splendid host at war with the second; we saw the billmen of fair Bascquerard and Bruneval lop down the olive mercenaries from Roquemaure and the cities of the midland sea; we saw the savage Genoese falcons rip open the gay livery of Lyons and Bayonne, and all the while our shafts rained thick and fast among them, and men fell dead by scores in that hideous turmoil—and none could tell whether ’twas friends or foes that slew them.

A wonderful day, indeed; but hard was the fighting ere it was done. My poor pen fails before all the crowded incident that comes before me, all the splendid episodes of a stirring combat, all the glitter and joy and misery, the proud exultation of that August morning and the black chagrin of its evening. Truth! But you must take as said a hundred times as much as I can tell you, and line continually my bare suggestions with your generous understanding.

Well, though our archers stood the first brunt, the day was not left all to them. Soon the French footmen, thirsting for vengeance, had overriden and trampled upon their Genoese allies, and came at us up the slope, driving back our skirmishers as the white squall drives the wheeling seamews before it, and surged against our palisades, and came tossing and glinting down upon our halberdiers. The loud English cheer echoed the wild yelling of the Southerners: bill and pike, and sword and mace and dagger sent up a thunderous roar all down our front, while overhead the pennons gleamed in the dusty sunlight, and the carrion crows wheeled and laughed with hungry pleasure above that surging line. Gods! ’twas a good shock, and the crimson blood went smoking down to the rivulets, and the savage scream of battle went up into the sky as that long front of ours, locked fast in the burnished arms of France, heaved and strove, and bent now this way and now that, like some strong, well-matched wrestlers.

A good shock indeed! A wild tremendous scene of confusion there on the long grass of that autumn hill, with the dark woods behind on the ridge, and, down in front, the babbling river and the smoking houses of the ruined village. So vast was the extent of Philip’s array that at times we saw it extend far to right and left of us; and so deep was it, that we who battled amid the thunder of its front could hear a mile back to their rear the angry hum of rage and disappointment as the chaotic troops, in the bitterness of the spreading confusion, struggled blindly to come at us. Their very number was our salvation. That half of the great army which had safely crossed the stream lay along outside our palisades like some splendid, writhing, helpless monster, and the long swell of their dead-locked masses, the long writhe of their fatal confusion, you could see heaving that glittering tide like the golden pulse of a summer sea pent up in a crescent shore. And we were that shore! All along our front the stout, unblenching English yeomen stood to it—the white English tunic was breast to breast with the leathern kirtles of Genoa and Turin. Before the frightful blows of those stalwart pikemen the yellow mail of the gay troopers of Châteauroux and Besaçon crackled like dry December leaves; the rugged boar-skins on the wide shoulders of Vosges peasants were less protection against their fiery thrust than a thickness of lady’s lawn. Down they lopped them, one and all, those strong, good English hedgemen, till our bloody foss was full—full of olive mercenaries from Tarascon and Arles—full of writhing Bisc and hideous screaming Genoese. And still we slew them, shoulder to shoulder, foot to foot, and still they swarmed against us, while we piled knight and vassal, serf and master, princeling and slave, all into that ditch in front. The fair young boy and gray-bearded sire, the freeman and the serf, the living and the dead, all went down together, till a broad rampart stretched along our swinging, shouting front, and the glittering might of France surged up to that human dam and broke upon it like the futile waves, and went to pieces, and fell back under the curling yellow stormcloud of mid-battle.

Meanwhile, on right and left, the day was fiercely fought. Far upon the one hand the wild Irish kerns were repelling all the efforts of Beaupreau’s light footmen, and pulling down the gay horsemen of fair Bourges by the distant Loire. Three times those squadrons were all among them, and three times the wild red sons of Shannon and the dim Atlantic hills fell on them like the wolves of their own rugged glens, and hamstrung the sleek Southern chargers, and lopped the fallen riders, and repelled each desperate foray, making war doubly hideous with their clamor and the bloody scenes of butchery that befell among their prisoners after each onset.

And, on the other crescent of our battle, my dear, tuneful, licentious Welshmen were out upon the slope, driving off with their native ardor one and all that came against them, and, worked up to a fine fury by their chanting minstrels, whose shrill piping came ever and anon upon the wind, they pressed the Southerners hard, and again and again drove them down the hill—a good, a gallant crew that I have ever liked, with half a dozen vices and a score of virtues! I had charged by them one time in the day, and, cantering back with my troop behind their ranks, I saw a young Welsh chieftain on a rock beside himself with valor and battle. He was leaping and shouting as none but a Welshman could or would, and beating his sword upon his round Cymric shield, the while he yelled to his fighting vassals below a fierce old British battle song. Oh! it was very strange for me, pent in that shining Plantagenet mail, to listen to those wild, hot words of scorn and hatred—I who had heard those words so often when the ancestors of that chanting boy were not begotten—I who had heard those fiery verses sung in the red confusion of forgotten wars—I who could not help pulling a rein a moment as that song of exultation, full of words and phrases none but I could fully understand, swelled up through the eddying war-dust over the Welshmen’s reeling line. I, so strong and young; I, who yet was more ancient than the singer’s vaguest traditions—I stopped a moment and listened to him, full of remembrance and sad wonder, while the pæan-dirge of victory and death swelled to the sky over the clamor of the combat. And then—as a mavis drops into the covert when his morning song is done—the Welshman finished, and, mad with the wine of battle, leaped straight into the tossing sea below, and was engulfed and swallowed up like a white spume-flake on the bosom of a wave.

For three long hours the battle raged from east to west, and men fought foot to foot and hand to hand, and ’twas stab and hack and thrust, and the pounding of ownerless horses and the wail of dying men, and the husky cries of captains, and the interminable clash of steel on steel, so that no man could see all the fight at once, save the good King alone, who sat back there at his vantage-point. It was all this, I say; and then, about seven in the afternoon, when the sun was near his setting, it seemed, all in a second, as though the whole west were in a glow, and there was Lord Alençon sweeping down upon our right with the splendid array of Philip’s chivalry, their pennons a-dance above and their endless ranks of spears in serried ranks below. There was no time to think, it seemed. A wild shout of fear and wonder went up from the English host. Our reserves were turned to meet the new danger; the archers poured their gray-goose shafts upon the thundering squadrons; princes and peers and knights were littered on the road that brilliant host was treading—and then they were among the English yeomen with a frightful crash of flesh and blood and horse and steel that drowned all other sound of battle with its cruel import! Jove! What strong stuff the English valor is! Those good Saxon countrymen, sure in the confidence of our great brotherhood, kept their line under that hideous shock as though each fought for a crown, and, shoulder to shoulder and hand to hand, an impenetrable living wall derided the terrors of the golden torrent that burst upon them. Happy King to yield such stuff—thrice-happy country that can rear it! In vain wave upon wave burst upon those hardy islanders, in vain the stern voice of Alençon sent rank after rank of proud lords and courtly gallants upon those rugged English husbandmen—they would not move, and when they would not the Frenchmen hesitated.

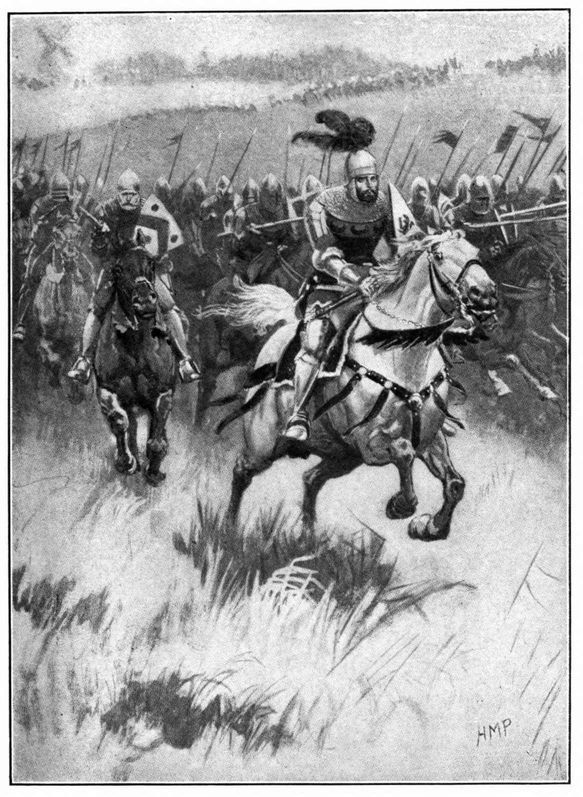

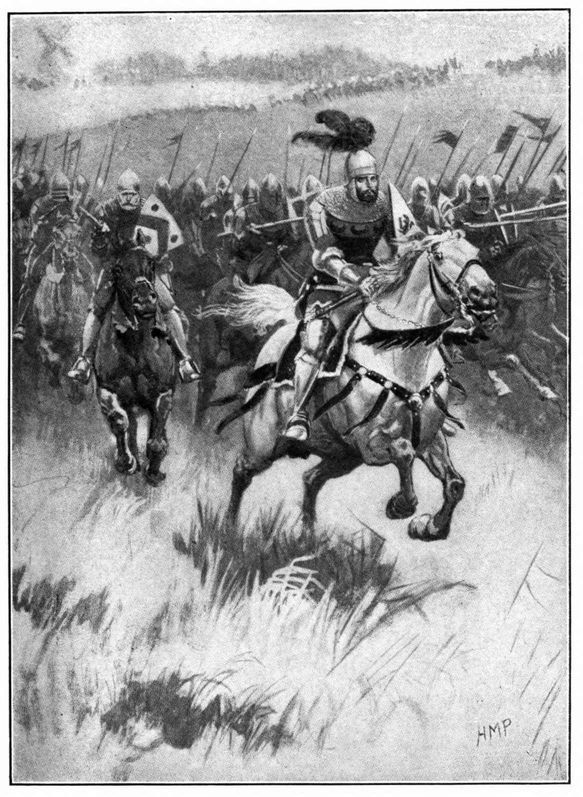

’Twas our moment! I had had my leave just then new from the King, and did not need it twice. I saw the great front of French cavalry heaving slow upon our hither face, galled by the arrow-rain that never ceased, and irresolute whether to come on once again or go back, and I turned to the cohort of my dear veterans. I do not know what I said, the voice came thick and husky in my throat, I could but wave my iron mace above my head and point to the Frenchmen. And then all those good gray spears went down as though ’twere one hand that lowered them, and all the chargers moved at once. I led them round the English front, and there, clapping spurs to our ready coursers’ flanks, five hundred of us, knit close together, with one heart beating one measure, shot out into array, and, sweeping across the slope, charged boldly ten thousand Frenchmen!

Five hundred of us charged boldly ten thousand Frenchmen!

We raced across the Crecy slope, drinking the fierce wine of expectant conflict with every breath, our straining chargers thundering in tumultuous rhythm over the short space between, and, in another minute, we broke upon the foemen. Bravely they met us. They turned when we were two hundred paces distant, and advancing with their silken fleur de lys, and pricking up their chargers, weary with pursuit and battle, they came at us as you will see a rock-thwarted wave run angry back to meet another strong incoming surge. And as those two waves meet, and toss and leap together, and dash their strength into each other, the while the white spume flies away behind them, and, with thunderous arrogance, the stronger bursts through the other and goes streaming on triumphant through all the white boil and litter of the fight, so fell we on those princelings. ’Twas just a blinding crash, the coming together of two great walls of steel! I felt I was being lifted like a dry leaf on the summit of that tremendous conjunction, and I could but ply my mace blindly on those glittering casques that shone all round me, and, I now remember, cracked under its meteor sweep like ripe nuts under an urchin’s hammer. So dense were the first moments of that shock of chivalry that even our horses fought. I saw my own charger rip open the glossy neck of another that bore a Frenchman; and near by—though I thought naught of it then—a great black Flemish stallion, mad with battle, had a wounded soldier in its teeth, and was worrying and shaking him as a lurcher worries a screaming leveret. So dense was the throng we scarce could ply our weapons, and one dead knight fell right athwart my saddle-bow; and a flying hand, lopped by some mighty blow, still grasping the hilt of a broken blade, struck me on the helm; the warm red blood spurting from a headless trunk half blinded me—and, all the time, overhead the French lilies kept stooping at the English lion, and now one went down and then the other, and the roar of the host went up into the sky, and the dust and turmoil, the savage uproar, the unheard, unpitied shriek of misery and the cruel exultation of the victor, and then—how soon I know not—we were traveling!

Ah! by the great God of battles, we were moving—and forward—the mottled ground was slipping by us—and the French were giving! I rose in my stirrups, and, hoarse as any raven that ever dipped a black wing in the crimson pools of battle, shouted to my veterans. It did not need! I had fought least well of any in that grim company, and now, with one accord, we pushed the foeman hard. We saw the great roan Flanders jennets slide back upon their haunches, and slip and plunge in the purple quagmire we had made, and then—each like a good ship well freighted—lurch and go down, and we stamped beribboned horse and jeweled rider alike into the red frothy marsh under our hoofs. And the fleur de lys sank, and the silver roe of Mayenne, proud Montereau’s azure falcon, and the white crescent of Donzenac went down, and Bernay’s yellow cornsheaf and Sarreburg’s golden blazon, with many another gaudy pennon, and then, somehow, the foemen broke and dissolved before our heavy, foam-streaked chargers, and, as we gasped hot breath through our close helmet-bars, there came a clear space before us, with flying horsemen scouring off on every hand.

The day was wellnigh won, and I could see that far to left the English yeomen were driving the scattered clouds of Philip’s footmen pell-mell down the hill, and then we went again after his horsemen, who were gathering sullenly upon the lower slopes. Over the grass we scoured like a brown whirlwind, and in a minute were all among the French lordlings. And down they went, horse and foot, riders and banners, crowding and crushing each other in a confusion terrible to behold, now suffering even more from their own chaos than from our lances. Jove! brother trod brother down that day, and comrade lay heaped on living comrade under that red confusion. The pennons—such as had outlived the storm so far—were all entangled sheaves, and sank, whole stocks at once, into the floundering sea below. And kings and princes, hinds and yeomen, gasped and choked and glowered at us, so fast-locked in the deadly wedge that went slowly roaring back before our fiery onsets, they could not move an arm or foot!

The tale is nearly told. Everywhere the English were victorious, and the Frenchmen fell in wild dismay before them. Many a bold attempt they made to turn the tide, and many a desperate sally and gallant stand the fading daylight witnessed. The old King of Bohemia, to whom daylight and night were all as one, with fifty knights, their reins knotted fast together, charged us, and died, one and all, like the good soldiers that they were. And Philip, over yonder, wrung his white hands and pawned his revenue in vows to the unmoved saints; and the soft, braggart peers that crowded round him gnawed their lips and frowned, and looked first at the ruined, smoldering fight, then back—far back—to where, in the south, friendly evening was already holding out to them the dusky cover of the coming night. It was a good day indeed, and may England at her need ever fight so well!

Would that I might in this truthful chronicle have turned to other things while the long roar of exultation goes up from famous Crecy and the strong wine of well-deserved victory filled my heart! Alas! there is that to tell which mars the tale and dims the shine of conquest.

Already thirty thousand Frenchmen were slain, and the long swathes lay all across the swelling ground like the black rims of weed when the sea goes back. Only here and there the battle still went on, where groups and knots of men were fighting, and I, with my good comrade Flamaucœur, now, at sunset, was in such a mêlée on the right. All through the day he had been like a shadow to me—and shame that I have said so little of it! Where I went there he was, flitting in his close gray armor close behind me; quick, watchful, faithful, all through the turmoil and dusty war-mist; escaping, Heaven knows how, a thousand dangers; riding his light war-horse down the bloody lanes of war as he ever rode it, as if they two were one; gentle, retiring, more expert in parrying thrust and blow than in giving—that dear friend of mine, with a heart made stout by consuming love against all its native fears, had followed me.

And now the spent battle went smoldering out, and we there thought ’twas all extinguished, when, all on a sudden—I tell it less briefly than it happened—a desperate band of foemen bore down on us, and, as we joined, my charger took a hurt, and went crashing over, and threw me full into the rank tangle of the under fight. Thereon the yeomen, seeing me fall, set up a cry, and, with a rush, bore the Frenchmen four spear-lengths back, and lifted me, unhurt, from the littered ground. They gave me a sword, and, as I turned, from the foemen’s ranks, waving a beamy sword, plumed by a towering crest of nodding feathers and covered by a mighty shield, a gigantic warrior stepped out. Hoth! I can see him now, mad with defeat and shame, striding on foot toward us—a giant in glittering, pearly armor, that shone and glittered as the last rays of the level sun against the black backing of the evening sky, as though its wearer had been the Archangel Gabriel himself! It did not need to look upon him twice: ’twas the Lord High Constable of France himself—the best swordsman, the sternest soldier, and the brightest star of chivalry in the whole French firmament. And if that noble peer was hot for fight, no less was I. Stung by my fall, and glorying in such a foeman, I ran to meet him, and there, in a little open space, while our soldiers leaned idly on their weapons and watched, we fought. The first swoop of the great Constable’s humming falchion lit slanting on my shield and shore my crest. Then I let out, and the blow fell on his shield, and sent the giant staggering back, and chipped the pretty quarterings of a hundred ancestors from that gilded target. At it again we went, and round and round, raining our thunderous blows upon each other with noise like boulders crashing down a mountain valley. I did not think there was a man within the four seas who could have stood against me so long as that fierce and bulky Frenchman did. For a long time we fought so hard and stubborn that the blood-miry soil was stamped into a circle where we went round and round, raining our blows so strong, quick, and heavy that the air was full of tumult, and glaring at each other over our morion bars, while our burnished scales and links flew from us at every deadly contact, and the hot breath steamed into the air, and the warm, smarting blood crept from between our jointed harness. Yet neither would bate a jot, but, with fiery hearts and heaving breasts and pain-bursting muscles, kept to it, and stamped round and round those grimy, steaming lists, redoubtable, indomitable, and mad with the lust of killing.

And then—Jove! how near spent I was!—the great Constable, on a sudden, threw away his many-quartered shield, and, whirling up his sword with both hands high above his head, aimed a frightful blow at me. No mortal blade or shield or helmet could have withstood that mighty stroke! I did not try, but, as it fell, stepped nimbly back—’twas a good Saxon trick, learned in the distant time—and then, as the falchion-point buried itself a foot deep in the ground, and the giant staggered forward, I flew at him like a wild cat, and through the close helmet-bars, through teeth and skull and the three-fold solid brass behind, thrust my sword so straight and fiercely, the smoking point came two feet out beyond his nape, and, with a lurch and cry, the great peer tottered and fell dead before me.

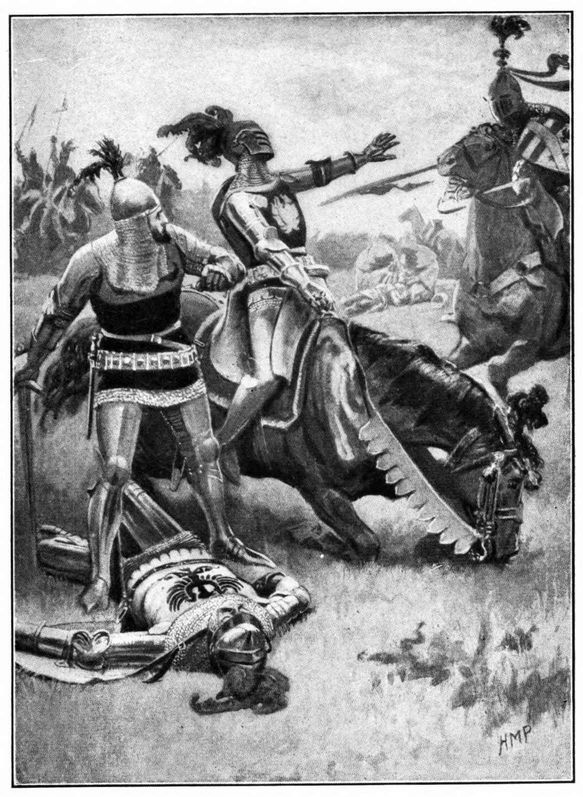

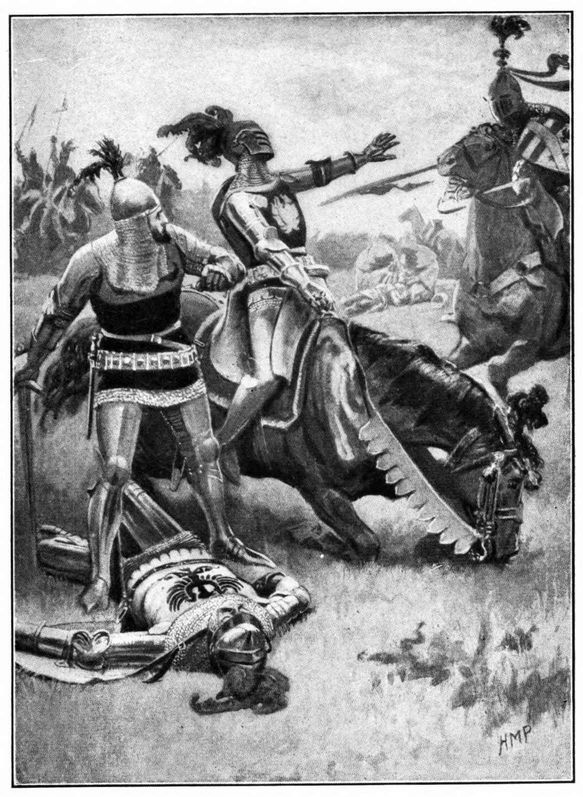

Now comes that thing to which all other things are little, the fellest gleam of angry steel of all the steel that had shone since noon, the cruelest stab of ten thousand stabs, the bitterest cry of any that had marred the full yellow circle of that August day! I had dropped on one knee by the champion, and, taking his hand, had loosed his visor, and shouted to two monks, who were pattering with bare feet about the field (for, indeed, I was sorry, if perchance any spark of life remained, so brave a knight should die unshriven to his contentment), and thus was forgotten for the moment the fight, the confronting rows of foemen, and how near I was to those who had seen their great captain fall by my hands. Miserable, accursed oversight! I had not knelt by my fallen enemy a moment, when suddenly my men set up a cry behind me, there was a rush of hoofs, and, ere I could regain my feet or snatch my sword or shield, a great black French rider, like a shadowy fury dropped from the sullen evening sky, his plumes all streaming behind him, his head low down between his horse’s ears, and his long blue spear in rest, was thundering in mid career against me not a dozen paces distant. As I am a soldier, and have lived many ages by my sword, that charge must have been fatal. And would that it had been! How can I write it? Even as I started to my feet, before I could lift a brand or offer one light parry to that swift, keen point, the horseman was upon me. And as he closed, as that great vengeance-driven tower of steel and flesh loomed above me, there was a scream—a wild scream of fear and love—(and I clap my hands to my ears now, centuries afterward, to deaden the undying vibrations of that sound)—and Flamaucœur had thrown himself ’tween me and the spear-point, had taken it, fenceless, unwarded, full in his side, and I saw the cruel shaft break off short by his mail as those four, both horses and both riders, went headlong to the ground.

Flamaucœur had taken it full in his side

Up rose the English with an angry shout, and swept past us, killing the black champion as they went, and driving the French before them far down into the valley. Then ran I to my dear comrade, and knelt and lifted him against my knee. He had swooned, and I groaned in bitterness and fear when I saw the strong red tide that was pulsing from his wound and quilting his bright English armor. With quick, nervous fingers—bursting such rivets as would not yield, all forgetful of his secret, and that I had never seen him unhelmed before—I unloosed his casque, and then gently drew it from his head.

With a cry I dropped the great helm, and wellnigh let even my fair burden fall, for there, against my knee, her white, sweet face against my iron bosom, her fair yellow hair, that had been coiled in the emptiness of her helmet, all adrift about us, those dear curled lips that had smiled so tender and indulgent on me, her gentle life ebbing from her at every throe, was not Flamaucœur, the unknown knight, the foolish and lovesick boy, but that wayward, luckless girl Isobel of Oswaldston herself!

And if I had been sorry for my companion in arms, think how the pent grief and surprise filled my heart, as there, dying gently in my arms, was the fair girl whom, by a tardy, late-born love, new sprung into my empty heart, I had come to look upon as the point of my lonely world, my fair heritage in an empty epoch, for the asking!

Soon she moved a little, and sighed, and looked up straight into my eyes. As she did so the color burnt for a moment with a pale glow in her cheeks, and I felt the tremor of her body as she knew her secret was a secret no longer. She lay there bleeding and gasping painfully upon my breast, and then she smiled and pulled my plumed head down to her and whispered:

“You are not angry?”

Angry? Gods! My heart was heavier than it had been all that day of dint and carnage, and my eyes were dim and my lips were dry with a knowledge of the coming grief as I bent and kissed her. She took the kiss unresisting, as though it were her right, and gasped again:

“And you understand now all—everything? Why I ransomed the French maiden? Why I would not write for thee to thy unknown mistress?”

“I know—I know, sweet girl!”

“And you bear no ill-thought of me?”

“The great Heaven you believe in be my witness, sweet Isobel! I love you, and know of nothing else!”

She lay back upon me, seeming to sleep for a moment or two, then started up and clapped her hands to her ears, as if to shut out the sound of bygone battle that no doubt was still thundering through them, then swooned again, while I bent in sorrow over her and tried in vain to soothe and stanch the great wound that was draining out her gentle life.

She lay so still and white that I thought she were already dead; but presently, with a gasp, her eyes opened, and she looked wistfully to where the western sky was hanging pale over the narrow English sea.

“How far to England, dear friend?”

“A few leagues of land and water, sweet maid!”

“Could I reach it, dost thou think?” But then, on an instant, shaking her head, she went on: “Nay, do not answer; I was foolish to ask. Oh! dearest, dearest sister Alianora! My father—my gentlest father! Oh! tell them, Sir, from me—and beg them to forgive!” And she lay back white upon my shoulder.

She lay, breathing slow, upon me for a spell, then, on a sudden, her fair fingers tightened in my mailed hand, and she signed that she would speak again.

“Remember that I loved thee!” whispered Isobel, and, with those last words, the yellow head fell back upon my shoulder, the blue eyes wavered and sank, and her spirit fled.

Back by the lines of gleeful shouting troops—back by where the laughing English knights, with visors up, were talking of the day’s achievements—back by where the proud King, hand in hand with his brave boy, was thanking the south English yeomen for Crecy and another kingdom—back by where the champing, foamy chargers were picketed in rows—back by the knots of archers, all, like honest workmen, wiping down their unstrung bows—back by groups of sullen prisoners and gaudy heaps of captured pennons, we passed.

In front four good yeomen bore Isobel upon their trestled spears; then came I, bareheaded—I, kinsmanless, to her in all that camp the only kin; and then our drooping chargers, empty-saddled, led by young squires behind, and seeming—good beasts!—to sniff and scent the sorrow of that fair burden on ahead. So we went through the victorious camp to our lodgment, and there they placed Isobel on her bare soldier couch, her feet to the door of her soldier tent, and left us.