CHAPTER XVI

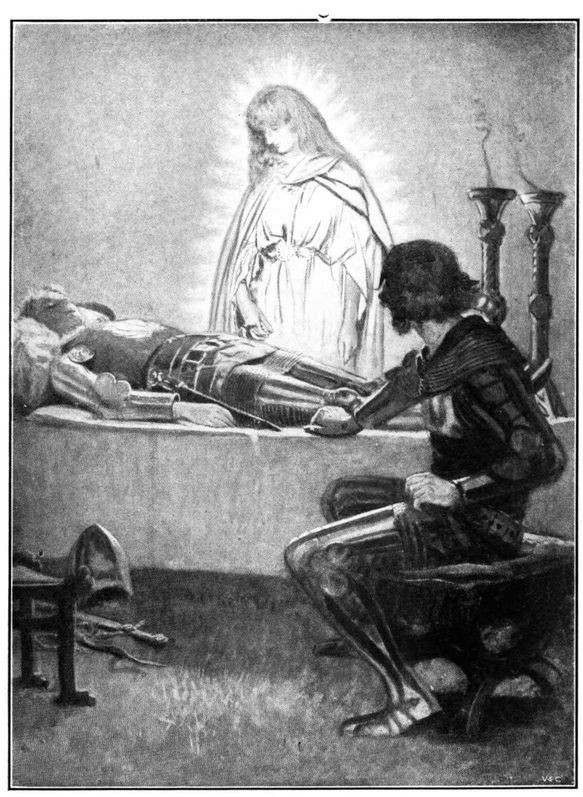

Unwashed, unfed, my dinted armor on me still—battle-stained and rent—unhelmeted, ungloved, my sword and scabbard cast by my hollow shield in a dark corner of the tent, I watched, tearless and stern, all that night by the bier of the pale white girl who had given so much for me and taken so poor a reward. I, who, so fanciful and wayward, had thought I might safely toy with the sweet tender of her affection—sprung how or why I knew not—and take or leave it as seemed best to my convenience, brooded, all the long black watch, over that gentle broken vessel that lay there white and still before me, alike indifferent to gifts or giving. And now and then I would start up from the stool I had drawn near to her, and pace, with bent head and folded arms, the narrow space, remembering how warm the rising tide of love had been flowing in my heart for that fair dead thing so short a time before. “So short a time before!” Why, it was but yesterday that she wrote for me that missive to herself: and I, fool and blind, could not read the light that shone behind those gray visor-bars as she penned the lines, or translate the tremor that shook that sweet scribe’s fingers, or recognize the heave of the maiden bosom under its steel and silk! I groaned in shame and grief, and bent over her, thinking how dear things might have been had they been otherwise, and loving her no whit the less because she was so cold, immovable, saying I know not what into her listless ear, and nourishing in loneliness and solitude, all those long hours, the black flower of the love that was alight too late in my heart.

I would not eat or rest, though my dinted armor was heavy as lead upon my spent and weary limbs—though the leather jerkin under that was stiff with blood and sweat, and opened my bleeding wounds each time I moved. I would not be eased of one single smart, I thought—let the cursed seams and gashes sting and bite, and my hot flesh burn beneath them! mayhap ’twould ease the bitter anger of my mind—and I repulsed all those who came with kind or curious eyes to the tent door, and would not hear of ease or consolation. Even the King came down, and, in respect to that which was within, dismounted and stood like a simple knight without, asking if he might see me. But I would not share my sorrow with any one, and sent the page who brought me word that the King was standing in the porch to tell him so; and, accomplished in courtesy as in war, the victorious monarch bent his head, and mounted, and rode silently back to his own lodging.

The gay gallants who had known me came on the whisper of the camp one by one (though all were hungry and weary), and lifted the flap a little, and said something such as they could think of, and peered at me, grimly repellent, in the shadows, and peeped curiously at that fair white soldier lain on the trestles in her knightly gear so straight and trim, and went away without daring to approach more nearly. My veterans clipped their jolly soldier-songs, though they had well deserved them, and took their suppers silently by the flickering camp-fire. Once they sent him among them that I was known to like the best with food and wine and clean linen, but I would not have it, and the good soldier put them down on one side of the door and went back as gladly as he who retreats skin-whole from the cave where a bear keeps watch and ward. Last of all there came the fall of quieter feet upon the ground, and, in place of the clank of soldier harness, the rattle of the beads of rosaries and cross; and, looking out, there was the King’s own chaplain, bareheaded, and three gray friars behind him. I needed ghostly comfort just then as little as I needed temporal, and at first I thought to repulse them surlily; but, reflecting that the maid had ever been devout and held such men as these in high esteem, I suffered them to enter, and stood back while they did by her the ceremonial of their office. They made all smooth and fair about, and lit candles at her feet and gave her a crucifix, and sprinkled water, and knelt, throwing their great black shadows athwart the white shrine of my dear companion, the while they told their beads and the chaplain prayed. When they had done, the priest rose and touched me on the arm.

“Son,” he said, “the King has given an earl’s ransom to be expended in masses for thy leman’s soul.”

“Father,” I replied, “tender the King my thanks for what was well meant and as princely generous as becomes him. But tell him all the prayers thy convent could count from now till the great ending would not bleach this white maid’s soul an atom whiter. Earn your ransom if you will, but not here; leave me to my sorrow.”

“I will give your answer, soldier; but these holy brothers—the King wished it—must stay and share your vigil until the morning. It is their profession; their prayerful presence can ward off the spirits of darkness; weariness never sits on their eyes as it sits now on thine. Let them stay with thee; it is only fit.”

“Not for another ransom, priest! I will not brook their confederate tears—I will not wing this fair girl’s soul with their hireling prayers—out, good fellows, my mood is wondrous short, and I would not willing do that which to-morrow I might repent of.”

“But, brother——” said one monk, gently.

“Hence—hence! I have no brothers—go! Can you look on me here in this extremity, can you see my hacked and bleeding harness, and the shine of bitter grief in my eyes, and stand pattering there of prayers and sympathy? Out! Out! or by every lying relic in thy cloisters I add some other saints to thy chapter rolls!”

They went, and as the tent-flap dropped behind them and the sound of their sandaled feet died softly away into the gathering night, I turned sorrowful and sad to my watch. I drew a stool to the maiden bier, and sat and took her hand, so white and smooth and cold, and looked at the fair young face that death had made so passionless—that sweet mirror upon which, the last time we had been together in happiness, the rosy light of love was shining and sweet presumption and maiden shame were striving. And as I looked and held her hand the dim tent-walls fell away, and the painted lists rose up before me, and the littered flowers my quick, curveting charger stamped into the earth, and the blare of the heralds’ trumpets, the flutter of the ribbons and the gay tires of brave lords and fair ladies all centered round the daïs where those two fair sisters sat. Gods! was that long sigh the night-wind circling about my tent-flap or in truth the sigh of slighted Isobel, as I rode past her chair with the victor’s circlet on my spear-point and laid it at the footstool of her sister?

I bent over that fair white corpse, so sick in mind and body that all the real was unreal and all the unreal true. I saw the painted pageantry of her father’s hall again and the colored reflections of the blazoned windows on the polished corridors shine upon our dim and sandy floor, and down the long vistas of my aching memory the groups of men and women moved in a motley harmony of color—a fair shifting mosaic of pattern and hue and light that radiated and came back ever to those two fair English girls. I heard the rippling laughter on courtly lips, the whispered jest of gallants, and the thoughtless glee of damsels. I heard the hum and smooth praise that circled round the black elder sister’s chair, and at my elbow the father, saying, “My daughter; my daughter Isobel!” and started up, to find myself alone, and that sweet horrid thing there in the low flickering taper-light unmoved, unmovable.

I sat again, and presently the wavering shadows spread out into the likeness of great cedar branches casting their dusky shelter over the soft, sweet-scented ground; and, as the hushed air swayed to and fro those great velvet screens, Isobel stepped from them, all in white, and ran to me, and stopped, and clapped her hands before her eyes and on her throbbing bosom—then stretched those trembling fingers, beseechingly to me fresh from that sweet companionship—then down upon her knees and clipped me round with her fair white arms and turned back her head and looked upon me with wild, wet, yearning eyes and cheeks that burned for love and shame. I would not have it; I laughed with the bitter mockingness of one possessed by another love, and unwound those ivory bonds and pushed the fair maid back, and there against the dusk of leaf and branch she stood and wrung her fingers and beat her breast and spoke so sweet and passionate, that even my icy mood half thawed under the white light of her reckless love, and I let her take my hand and hold and rain hot kisses on it and warm pattering tears, till all the strength was running from me, and I half turned and my fingers closed on hers—but, gods! how cold they were! And with a stifled cry I woke again in the little tent, to find my hand fast locked in the icy fingers of the dead.

It was a long, weary night, and, sad as was my watch and hectic as the visions which swept through my heavy head, I would not quicken by one willing hour of sleep the sad duties of that gray to-morrow which I knew must come. At times I sat and stared into the yellow tapers, living the brief spell of my last life again—all the episode and change, all the hurry and glitter, and unrest that was forever my portion—and then, in spite of resolution, I would doze to other visions, outlined more brightly on the black background of oblivion; and then I started up, my will all at war with tired Nature’s sweet insistence, and paced in weary round our canvas cell, solitary but for those teeming thoughts and my own black shadow, which stalked, sullen and slow, ever beside me.

But who can deride the great mother for long? ’Twas sleep I needed, and she would have it; and so it came presently upon my heavy eyelids—strong, deep sleep as black and silent as the abyss of the nether world. My head sank upon my arm, my arm upon the foot of the velvet bier, and there, in my mail, under the thin taper-light, worn out with battle and grief, I slept.

I know not how long it was, some hours most likely, but after a time the strangest feeling took possession of me in that slumber, and a fine ethereal terror, purged of gross material fear, possessed my spirit. I awoke—not with the pleasant drowsiness which marks refreshment, but wide and staring, and my black Phrygian hair, without the cause of sight or sound, stood stiff upon my head, for something was moving in the silent tent.

I glared around, yet nothing could be seen: the lights were low in their sockets, but all else was in order: my piled shield and helmet lay there in the shadows, our warlike implements and gear were all as I had seen them last, no noise or vision broke the blank, and yet—and yet—a coward chill sat on me, for here and there was moving something unseen, unheard, unfelt by outer senses. I rose, and, fearful and yet angry to be cowed by a dreadful nothing, stared into every corner and shadow, but naught was there. Then I lifted a dim taper, and held it over the face of the dead girl and stared amazed! Were it given to mortals to die twice, that girl had! But a short time before and her sweet face had worn the reflection of that dreadful day: there was a pallid fright and pain upon it we could not smooth away, and now some wonderful strange thing had surely happened, and all the unrest was gone, all the pained dissatisfaction and frightened wonder. The maid was still and smooth and happy-looking. Hoth! as I bent over her she looked just as one might look who reads aright some long enigma and finds relief with a sigh from some hard problem. She slept so wondrous still and quiet, and looked so marvelous fair now, and contented, that it purged my fear, and, strong in that fair presence—how could I be else?—I sat, and after a time, though you may wonder at it, I slept again.

I dozed and dozed and dozed, in happy forgetfulness of the present while the black night wore on to morning, and the last faint flushes of the priestly tapers played softly in their sockets; and then again I started up with every nerve within me thrilling, my clenched fists on my knees, and my wide eyes glaring into the mid gloom, for that strange nothing was moving gently once more about us, fanning me, it seemed, with the rhythmed swing of unseen draperies, circling in soft cadenced circles here and there, mute, voiceless, presenceless, and yet so real and tangible to some unknown inner sense that hailed it from within me that I could almost say that now ’twas here and now ’twas there, and locate it with trembling finger, although, in truth, nothing moved or stirred.

I looked at the maid. She was as she had been; then into every dusky place and corner, but nothing showed; then rose and walked to the tent-flap and lifted it and looked out. Down in the long valley below the somber shadows were seamed by the winding of the pale river; and all away on the low meadows, piled thick and deep with the black mounds of dead foemen, the pale marsh lights were playing amid the corpses—leaping in ghostly fantasy from rank to rank, and heap to heap, coalescing, separating, shining, vanishing, all in the unbroken twilight silence. And those somber fields below were tapestried with the thin wisps of white mist that lay in the hollows, and were shredded out into weird shapes and forms over the black bosom of the near-spent night. Up above, far away in the east, where the low hills lay flat in the distance, the lappet fringe of the purple sky was dipped in the pale saffron of the coming sun, and overhead a few white stars were shining, and now and then the swart, almost unseen wings of a raven went gently beating through the star-lit void; and as I watched, I saw him and his brothers check over the Crecy ridges and with hungry croak, like black spirits, circle round and drop one after another through the thin white veils of vapor that shrouded prince, chiefs, and vassals, peer and peasant, in those deep long swathes of the black harvest we cut, but left ungarnered, yesterday. Near around me the English camp was all asleep, tired and heavy with the bygone battle, the listless pickets on the misty, distant mounds hung drooping over their piled spears, the metaled chargers’ heads were all asag, they were so weary as they stood among the shadows by their untouched fodder, and the damp pennons and bannerets over the knightly porches scarce lifted on the morning air! That air came cool and sad yonder from the English sea, and wandered melancholy down our lifeless, empty canvas streets, lifting the loose tent-flaps, and sighing as it strayed among the sleeping groups, stirring with its unseen feet the white ashes of the dead camp-fires, the only moving presence in all the place—sad, silent, and listless. I dropped the hangings over the chill morning glimmer, the camp of sleeping warriors and dusty valley of the dead, and turned again to my post. I was not sleepy now, nor afraid—even though as I entered a draught of misty outer air entered with me and the last atom of the priestly taper shone fitful and yellow for a moment upon the dead Isobel, and then went out.

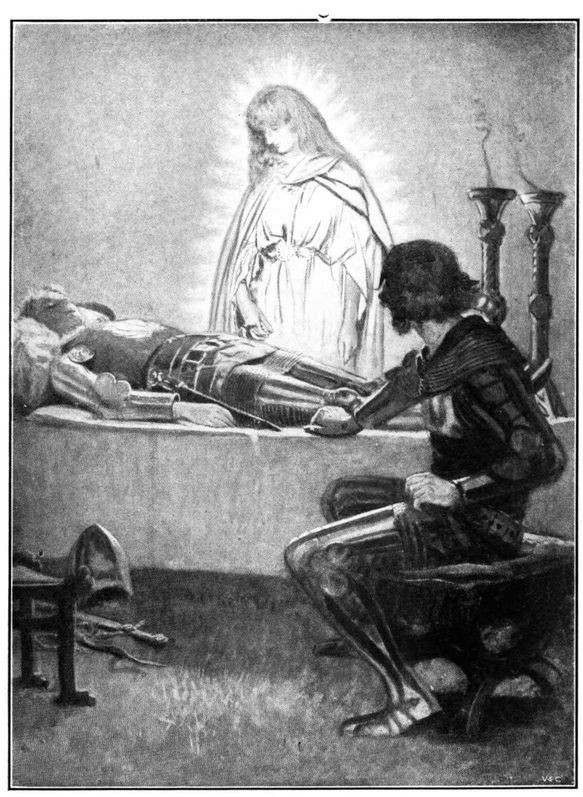

I sat down by the maid in the chill dark, and looked sadly on the ground, the while my spirits were as low as you may well guess, and the wind went moaning round and round the tent. But I had not sat a moment—scarcely twenty breathing spaces—when a faint, fine scent of herb-cured wolf-skins came upon the air, and strange shadows began to stand out clear upon the floor. I saw my weapons shining with a pale refulgence, and—by all the gods!—the walls of the tent were a-shimmer with pale luster! With a half-stifled cry I leaped to my feet, and there—there across the bier—though you tell me I lie a thousand times—there, calm, refulgent, looking gently in the dead girl’s face, splendid in her ruddy savage beauty, bending over that white marbled body, so ghostly thin and yet so real, so true in every line and limb, was Blodwen—Blodwen, the British chieftainess—my thousand-years-dead wife.

Looking gently in the dead girl’s face, was Blodwen—Blodwen—my thousand-years-dead wife

Standing there serene and lovely, with that strange lavender glow about her, was that wonderful and dreadful shade—holding the dead girl’s hand and looking at her closely with a face that spoke of neither resentment nor sorrow. I stood and stared at them, every wit within me numb and cold by the suddenness of it, and then the apparition slowly lifted her eyes to mine, and I—the wildest sensations of the strong old love and brand-new fear possessed me. What! do you tell me that affection dies? Why, there in that shadowed tent, so long after, so untimely, so strange and useless—all the old stream of the love I had borne for that beautiful slave-girl, though it had been cold and overlaid by other loves for a thousand years, welled up in my heart on a sudden. I made half a pace toward her, I stretched a trembling, entreating hand, yet drew it back, for I was mortal and I feared; and an ecstasy of pleasure filled my throbbing veins, and my love said: “On! she was thine once and must be now—down to thy knees and claim her!—what matters anything, if thou hast a lien upon such splendid loveliness!” and my coward flesh hung back cold and would not, and now back and now forward I swayed with these contending feelings, while that fair shadow eyed me with the most impenetrable calm. At last she spoke, with never a tone in her voice to show she remembered it was near three hundred years since she had spoken before.

“My Phœnician,” she said in soft monotone, looking at the dead Isobel who lay pale in the soft-blue shine about her, “this was a pity. You are more dull-witted than I thought.”

I bent my head but could not speak, and so she asked:

“Didst really never guess who it was yonder steel armor hid?”

“Not once,” I said, “O sweetly dreadful!”

“Nor who it was that stirred the white maid to love over there in her home?”

“What!” I gasped. “Was that you?—was that your face, then, in truth I saw, reflecting in this dead girl’s when first I met her?”

“Why, yes, good merchant. And how you could not know it passes all comprehension.”

“And then it was you, dear and dreadful, who moved her? Jove! ’twas you who filled her beating pulses there down by the cedars, it was you who prompted her hot tongue to that passionate wooing? But why—why?”

That shadow looked away for a moment, and then turned upon me one fierce, fleeting glance of such strange, concentrated, unquenchable, impatient love that it numbed my tongue and stupefied my senses, and I staggered back, scarce knowing whether I were answered or were not.

Presently she went on. “Then, again, you are a little forgetful at times, my master—so full of your petty loves and wars it vexes me.”

“Vexes you! That were wonderful indeed; yet, ’tis more wonderful that you submit. One word to me—to come but one moment and stand shining there as now you do—and I should be at your feet, strange, incomparable.”

“It might be so, but that were supposing such moments as these were always possible. Dost not notice, Phœnician, how seldom I have been to thee like this, and yet, remembering that I forget thee not, that mayhap I love thee still, canst thou doubt but that wayward circumstance fits to my constant wish but seldom?”

“Yet you are immortal; time and space seem nothing; barriers and distance—all those things that shackle men—have no meaning for you. All thy being formed on the structure of a wish and every earthly law subservient to your fancy, how is it you can do so much and yet so little, and be at once so dominant and yet so feeble?”

“I told you, dear friend, before, that with new capacities new laws arise. I near forget how far I once could see—what was the edge of that shallow world you live in—where exactly the confines of your powers and liberty are set. But this I know for certain, that, while with us the possible widens out into splendid vagueness, the impossible still exists.”

“And do you really mean, then, that fate is still the stronger among you?—this fair girl, here, sweet shadow! Oh! with one of those terrible and shining arms crossed there on thy bosom, couldst thou not have guided into happy void that fatal spear that killed? Surely, surely, it were so easy!”

The priestess dropped her fair head, and over her dim-white shoulders, and her pleasant-scented, hazy wolf-skins, her ruddy hair, all agleam in that strange refulgence, shone like a cascade of sleeping fire. Then she looked up and replied, in low tones:

“The swimmer swims and the river runs, the wished-for point may be reached or it may not, the river is the stronger.”

Somehow, I felt that my shadowy guest was less pleased than before, so I thought a moment and then said: “Where is she now?” and glanced at Isobel.

“The novice,” smiled Blodwen, “is asleep.”

“Oh, wake her!” I cried, “for one moment, for half a breath, for one moiety of a pulse, and I will never ask thee other questions.”

“Insatiable! incredulous! how far will thy reckless love and wonder go? Must I lay out before thy common eyes all the things of the unknown for you to sample as you did your bags of fig and olive?”

“I loved her before, and I love her still, even as I loved and still love thee. Does she know this?”

“She knows as much as you know little. Look!” and the shadow spread out one violet hand over that silent face.

I looked, and then leaped back with a cry of fear and surprise. The dead girl was truly dead, not a muscle or a finger moved, yet, as at that bidding, I turned my eyes upon her there under the tender glowing shadow of that wondrous palm, a faint flush of colorless light rose up within her face, and on it I read, for one fleeting moment, such inexplicable knowledge, such extraordinary felicity, such impenetrable contentment, that I stood spellbound, all of a tremble, while that wondrous radiance died away even quicker than it had risen. Gods! ’twas like the shine of the herald dawn on a summer morning, it was like the flush on the water of a coming sunrise—I drew my hand across my face and looked up, expecting the chieftainess would have gone, but she was still there.

“Are you satisfied for the moment, dear trader, or would you catechize me as you did just now yonder by the fire under the altar in the circle?”

“Just now!” I exclaimed, as her words swept back to me the remembrance of the stormy night in the old Saxon days when, with the fair Editha asleep at my knee, that shade had appeared before—“just now! Why, Shadow, that was three hundred years ago!”

“Three hundred what?”

“Three hundred years—full round circles, three hundred varying seasons. Why, Blodwen, forests have been seeded, and grown venerable, and decayed about those stones since we were there!”

“Well, maybe they have. I now remember that interval you call a year, and what strange store we set by it, and I dimly recollect,” said the dreamy spirit, “what wide-asunder episodes those were between the green flush of your forests and the yellow. But now—why, the grains of sand here on thy tent-floor are not set more close together—do not seem more one simple whole to you, than your trivial seasons do to me. Ah! dear merchant, and as you smile to see the ripples of the sea sparkle a moment in frolic chase of one another, and then be gone into the void from whence they came, so do we lie and watch thy petty years shine for a moment on the smooth bosom of the immense.”

Deep, strange, and weird seemed her words to me that night, and much she said more than I have told I could not understand, but sat with bent head and crossed arms full of strange perplexity of feeling, now glancing at the dead soldier-maid my body loved, and then looking at that comely column of blue woman-vapor, that sat so placid on the foot of the bier and spoke so simply of such wondrous things.

For an hour we talked, and then on a sudden Blodwen started to her feet and stood in listening attitude. “They are coming, Phœnician,” she cried, and pointed to the door.

I arose with a strange, uneasy feeling and looked out. The gray dawn had spread from sky to sky, and an angry flush was over all the air. The morning wind blew cold and melancholy, and the shrouded mists, like bands of pale specters, were trooping up the bloody valley before it, but otherwise not a soul was moving, not a sound broke the ghostly stillness. I dropped the awning, and shook my head at the fair priestess, whereon she smiled superior, as one might at a wayward child, and for a minute or two we spoke again together. Then up she got once more, tall and stately, with dilated nostrils and the old proud, expectant look I had seen on her sweet red face so often as we together, hand in hand, and heart to heart, had galloped out to tribal war. “They come, Phœnician, and I must go,” she whispered, and again she pointed to the tent-door, though never a sound or footfall broke the stillness.

“You shall not, must not go, wife, priestess, Queen!” I cried, throwing myself on my knee at those shadowy feet, and extending my longing arms. “Oh! you that can awake, put me to sleep—you, that can read to the finish of every half-told tale, relieve me of the long record of my life! Oh, stay and mend my loneliness, or, if you go, let me come too—I ask not how or whither.”

“Not yet,” she said, “not yet——” And then, while more seemed actually upon her lips, I did hear the sound of footfalls outside, and, wondering, I sprang to the curtain and lifted it.

There, outside, standing in the first glint of the yellow sunshine, were some half-dozen of my honest veterans, all with spades and picks and in their leathern doublets.

“You see, Sir,” said the spokesman, sorrowfully, the while he scraped the half-dry clay from off his trenching spade, “we have come round for our brave young captain—for your good lady, Sir—the first. Presently we shall be very busy, and we thought mayhap you would like this over as soon and quiet as might be.”

They had come for Isobel! I turned back into the tent, wondering what they would think of my strange guest, and she was gone! Not one ray of light was left behind—not one thread of her lavender skirt shone against my black walls—only the cold, pale girl there, stiff and white, with the shine of the dawn upon her dead face; and all my long pain and vigils told upon me, and, with a cry of pain and grief I could not master, I dropped upon a seat and hid my face upon my arm.

I had had enough of France with that night, and three hours afterward went straight to the King and told him so, begging him to relieve me from my duty and let me get back to England, there to seek the dead maid’s kindred, and find in some new direction forgetfulness of everything about the victorious camp. And to this the King replied, by commending my poor service far too highly, saying some fair kind things out of his smooth courtier tongue about her that was no more, and in good part upbraiding me for bringing, as he supposed I had brought, one so gentle-nurtured so far afield; then he said: “In faith, good soldier, were to-day but yesterday, and Philip’s army still before us, we would not spare you even though our sympathy were yours as fully as ’tis now. But my misguided cousin is away to Paris, and his following are scattered to the four winds—for which God and all the saints be thanked! There is thus less need for thy strong arm and brave presence in our camp, and if you really would—why then, go, and may kind time heal those wounds which, believe me, I do most thoroughly assess.”

“But stay a minute!” he cried after me. “How soon could you make a start?”

“I have no gear,” I said, “and all my prisoners have been set free unransomed. I could start here, even as I stand.”

“Soldierly answered,” exclaimed the King; “a good knight should have no baggage but his weapons, and no attachments but his duty. Now look! I can both relieve you of irksome charges here and excuse with reason both ample and honorable your going. Come to me as soon as you have put by your armor. I will have ready for you a scrip sealed and signed—no messenger has yet gone over to England with the news of our glorious yesterday, and this charge shall be thine. Take the scrip straight to the Queen in England. There, no thanks, away! away! thou wilt be the most popular man in all my realm before the sun goes down, I fear.”

I well knew how honorable was this business that the good King had planned for me, and made my utmost despatch. I gave my tent to one esquire and my spare armor to another. I ran and gripped the many bronzed hands of my tough companions, and told them (alas! unwittingly what a lie that were!) that I would come again; then I bestowed my charger (Jove! how reluctant was the gift!) upon the next in rank below me, and mounted Isobel’s light war-horse, and paid my debts, and settled all accounts, and was back at our great captain’s tent just as his chaplain was sanding the last lines upon that despatch which was to startle yonder fair country waiting so expectant across the narrow sea.

They rolled it up in silk and leather and put it in a metal cylinder, and shut the lid and sealed it with the King’s own seal, and then he gave it to me.

“Take this,” he said, “straight to the Queen, and give it into her own hands. Be close and silent, for you will know it were not meet to be robbed of thy news upon the road: but I need not tell you of what becomes a trusty messenger. There! so, strap it in thy girdle, and God speed thee—surely such big news was never packed so small before.”

I left the Royal tent and vaulted into the ready saddle without. One hour, I thought, as the swift steed’s head was turned to the westward, may take me to the shore, and two others may set me on foot in England. Then, if they have relays upon the road, three more will see me kneeling at the lady’s feet, the while her fingers burst these seals. Lord! how they shall shout this afternoon! how the ’prentices shall toss their caps, and the fat burghers crowd the narrow streets, and every rustic hamlet green ring to the sky with gratitude! Ah! six hours I thought might do the journey; but read, and you shall see how long it took.

Scouring over the low grassy plains as hard as the good horse could gallop, with the gray sea broadening out ahead with every mile we went, full of thoughts of a busy past and uncertain future, I hardly noticed how the wind was freshening. Yet, when we rode down at last by a loose hill road to the beach, strong gusts were piping amid the treetops, and the King’s galleys were lurching and rolling together at their anchors by the landing-stage as the short waves came crowding in, one close upon another, under the first pressure of a coming storm.

But, wind or no wind, I would cross; and I spoke to the captain of the galleys, showing him my pass with its Royal signet, and saying I must have a ship at once, though all the cave of Eblis were let loose upon us. That worthy, weather-beaten fellow held the mandate most respectfully in one hand, while he pulled his grizzled beard with the other and stared out into the north, where, under a black canopy of lowering sky, the sea was seamed with gray and hurrying squalls, then turned to the cluster of sailors who were crowded round us—guessing my imperious errand—to know who would start upon it. And those rough salts swore no man of sanity would venture out—not even for a King’s generous bounty—not even to please victorious Edward would they go—no, nor to ease the expectant hearts of twenty thousand wives, or glad the proud eyes of ten score hundred mothers. It was impossible, they said—see how the frothy spray was flying already over the harbor bar, and how shrill the frightened sea-mews were rising high above the land!—no ship would hold together in such a wind as that brewing out over there, no man this side of hell could face it—and yet, and yet, “Why!” laughed a leathery fellow, slapping his mighty fist into his other palm, “as I was born by Sareham, and knew the taste of salt spray nearly as early as I knew my mother’s milk, it shall never be said I was frightened by a hollow sky and a Frenchman’s wind. I’ll be your pilot, Sir.”

“And I will go wherever old Harry dares,” put in a stout young fellow. “And I,” “And I,” “And I,” was chorused on every side, as the brave English seamen caught the bold infection, and in a brief space there, under the lee of the gray harbor jetty, before a motley cheering crowd, all in the blustering wind and rain, I rode my palfrey up the sloping way, and on to the impatient tossing little bark that was to bear the great news to England.

We stabled the good steed safe under the half-deck forward, set the mizzen and cast off the hawser, and soon the little vessel’s prow was bursting through the crisp waves at the harbor mouth, her head for home, and behind, dim through the rainy gusts, the white house-fronts of the beach village, and far away the uplands where the English army lay. We reefed and set the sails as we drew from the land, but truly those fellows were right when they hung back from sharing the peril and the glory with me! The strong blue waters of the midland sea whereon I first sailed my merchant bark were like the ripples of a sheltered pond to the roaring trench and furrows of this narrow northern strait. All day long we fought to westward, and every hour we spent the wind came stronger and more keenly out of the black funnel of the north, and the waves swelled broader and more monstrous. By noon we saw the English shore gleam ghostly white through the flying reek in front; but by then, so fierce was the northeaster howling, that, though we went to windward and off again, doing all that good seamen could, now stealing a spell ahead, and anon losing it amid a blinding squall, we could not near the English port for which we aimed, there, in the cleft of the dim white cliffs.

After a long time of this, our captain came to me where I leaned, watchful, against the mast, and said:

“The King has made an order, as you will know, all vessels from France are to sail for his town of Dover there, and nowhere else, on a pain of a fine that would go near to swamp such as we.”

“Good skipper,” I answered, “I know the law, but there are exceptions to every rule, which, well taken, only cast the more honor on general stringency. King Edward would have you make that port at all reasonable times; but if you cannot reach it, as you surely cannot now, you are not bound to sail me, his messenger, to Paradise in lieu thereof. I pray you, put down your helm and run, and take the nearest harbor the wind will let us.” At this the captain turned upon his heel well pleased, and our ship came round, and now, before the gale, sailed perhaps a little easier.

But it scarcely bettered our fortune. A short time before dusk, while we wallowed heavily in the long furrows, my poor palfrey was thrown and broke her fore legs over her trestle bar, and between fear and pain screamed so loud and shrill, it chilled even my stalwart sailors. Then, later on, as we rode the frothy summit of a giant wave, our topmast snapped, and fell among us and the wild, loose ropes writhed and lashed about worse than a hundred biting serpents, and the bellowing sail, like a great bull, jerked and strained for a moment so that I thought that it would unstep the mast itself, and then went all to tatters with a hollow boom, while we, knee-deep in the swirling sea that filled our hollow, deckless ship, gentle and simple, ’prentice and knight, whipped out our knives and gave over to the hungry ocean all that riven tackle.

It was enough to make the stoutest heart beat low to ride in such a creaking, retching cockle-shell over the hill and dale of that stupendous water. Now, out of the tumble and hiss, down we would go, careering down the glassy side of a mighty green slope, the creamy white water boiling under our low-sunk bows, and there, in mid-hollow, with the tempest howling overhead, we would have for a breathing space a blessed spell of seeming calm. And then, ere we could taste that scant felicity, the reeling floor would swell beneath us, and out of the watery glen, hurtled by some unseen power, we rose again up, up to the spume and spray, to the wild shouting wind that thrilled our humming cordage and lay heavy upon us, while the gleaming turmoil through which we staggered and rushed leaped at our fleeting sides like packs of white sea-wolves, and all the heaving leaden distance of the storm lay spread in turn before us—then down again.

Hour after hour we reeled down the English coast with the wild mid-channel in fury on our left and the dim-seen ramparts of breakers at the cliff feet on our right. Then, as we went, the light began to fail us. Our weather-beaten steersman’s face, which had looked from his place by the tiller so calm and steadfast over the war of wind and sea, became troubled, and long and anxiously he scanned the endless line of surf that shut us from the many little villages and creeks we were passing.

“You see, Sir Knight,” shouted the captain to me, as, wet through, we held fast to the same rope—“’tis a question with us whether we find a shelter before the light goes down, or whether we spend a night like this out on the big waters yonder.”

“And does he,” I asked, “who pilots us know of a near harbor?”

“Ah! there is one somewhere hereabout, but with a perilous bar across the mouth, and the tide serves but poorly for getting over. If we can cross it there is a dry jacket and supper for all this evening, and if we do not, may the saints in Paradise have mercy on us!”

“Try, good fellow, try!” I shouted; “many a dangerous thing comes easier by the venturing, and I am already a laggard post!” So the word was passed for each man to stand by his place, and through the gloom and storm, the beating spray and the wild pelting rain, just as the wet evening fell, we neared the land.

We swept in from the storm, and soon there was the bar plain enough—a shining, thunderous crescent—glimmering pallid under the shadow of the land, a frantic hell of foam and breakers that heaved and broke and surged with an infernal storm-deriding tumult, and tossed the fierce white fountains of its rage mast-high into the air, and swirled and shone and crashed in the gloom, sending the white litter of its turmoil in broad ghostly sheets far into that black still water we could make out beyond under the veil of spume and foam hanging above that boiling caldron. Straight to it we went through the cold, fierce wind, with the howl of the black night behind us, and the thunder of that shine before. We came to the bar, and I saw the white light on the strained brave faces of my silent friends. I looked aft, and there was the helmsman calm and strong, unflinchingly eyeing the infernal belt before us. I saw all this in a scanty second, and then the white hell was under our bows and towering high above our stern a mighty crested, foam-seamed breaker. With the speed of a javelin thrown by a strong hand, we rushed into the wrack; one blinding moment of fury and turmoil, and then I felt the vessel stagger as she touched the sand; the next instant her sides went all to splinters under my very feet, and the great wave burst over us and rushed thundering on in conscious strength, and not two planks of that ill-fated ship, it seemed, were still together.

Over and over through the swirl and hum I was swept, the dying cries of my ship-fares sounding in my ears like the wail of disembodied spirits—now, for a moment, I was high in the spume and ruck, gasping and striking out as even he who likes his life the least will gasp in like case, and then, with thunderous power, the big wave hurled me down into the depth, down, down, into the inky darkness with all the noises of Inferno in my ears, and the great churning waters pressing on me till the honest air seemed leagues above, and my strained, bursting chest was dying for a gasp. Then again, the hideous, playful waters would tear asunder and toss me high into the keen, strong air, with the yellow stars dancing above, and the long line of the black coast before my salt tear-filled eyes, and propped me up just so long as I might get half a gasping sigh, and hear the storm beating wildly on the farther side of the bar; then the mocking sea would laugh in savage frolic, and down again. Gods! right into the abyss of the nether turmoil, fathoms deep, like a strand of worthless sea-wrack, scouring over the yellow sand-beds where never living man went before, all in the cruel fingers of the icy midnight sea, was I tossed here and there.

And when I did not die, when the savage sea, like a great beast of prey, let me live by gasps to spread its enjoyment the more, and tossed and teased me, and shouted so hideous in my ears and weighed me down—why, the last spark of spirit in me burnt up on a sudden, fierce and angry. I set my teeth and struck out hard and strong. Ah! and the sea grew somewhat sleek when I grew resolute, and, after some minutes of this new struggle, rolled more gently and buried me less deep each time in its black foam-ribbed vortex, and, presently, in half an hour perhaps, the thunder of the bar was all behind me instead of round about, the stars were steadier in their places, the dim barrier of the land frowned through the rain direct above, and a few minutes more, wondrous spent and weary, the black water flowing in at my low and swollen lips with every stroke, yet strong in heart and hopeful, I found myself floating up a narrow estuary on a dim, foam-flecked but peaceful tide.

The strong but gentle current swept in with the flowing water under the dark shadows of the land, past what seemed, in the wet night-gloom, like rugged banks of tree and forest, and finally floated me to where, among loose boulders and sand, the tamed water was lapping on a smooth and level beach. I staggered ashore, and sat down as wet and sorry as well could be. Life ran so cold and numb within, it seemed scarce worth the cost spent in keeping. My scrip was still at my side, but my sword was gone, my clothing torn to ribbons, and a more buffeted messenger never eyed askance the scroll that led him into such a plight. Where was I? The great gods who live forever alone could tell, yet surely scores of miles from where I should be! I got to my feet, reeking with wet and spray, the gusty wind tossing back the black Phrygian locks from off my forehead, and glared around. Sigh, sigh, sigh went the gale in the pines above, while mournful pipings came about the shore like wandering voices, and the sea boomed sullenly out yonder in the darkness! I stared and stared, and then started back a pace and stared again. I turned round on my heel and glowered up the narrow inlet and out to sea; then at the beetling crags above and the dim-seen mounds inland; then all on a sudden burst into a scornful laugh—a wild, angry laugh that the rocks bandied about on the wet night-air and sent back to me blended with all the fitful sobs and moaning of the wind.

The lonely harbor, that of a thousand harbors I had come to, was the old British beach. It was my Druid priestess’s village place that I was standing on!

I laughed long and loud as I, the old trader in wine and olives—I, the felucca captain, with cloth and wine below and a comely red-haired slave on deck—I, again, in other guise, Royal Edward’s chosen messenger—as good a knight as ever jerked a victorious brand home into its scabbard—stood there with chattering teeth and shaking knee, mocking fate and strange chance in reckless spirit. I laughed until my mood changed on a sudden, and then, swearing by twenty forgotten hierarchies I would not stand shivering in the rain for any wild pranks that Fate might play me, I staggered off on to the hard ground.

Every trace of my old village had long since gone; yet though it were a thousand years ago I knew my way about with a strange certainty. I left the shore, and pushed into the overhanging woods, dark and damp and somber, and presently I even found a well-known track (for these things never change); and, half glad and half afraid—a strange, tattered, dismal prodigal come strangely home—I pushed by dripping branch and shadowy coverts, out into the open grass hills beyond.

Here, on some ghostly tumuli near about, the gray shine of the night showed scattered piles of mighty stones and broken circles that once had been our temples and the burial places for great captains. I turned my steps to one of these on the elbow of a little ridge overlooking the harbor, and, perhaps, two hundred paces inland from it, and found a vast lichened slab of stupendous bulk undermined by weather, and all on a slope with a single entrance underneath one end. Did ever man ask lodgment in like circumstances? It was the burial mound of an old Druid headman, and I laughed a little again to think how well I had known him—grim old Ufner of the Reeking Altars. Hoth! what a cruel, bloody old priest he was!—never did a man before, I chuckled, combine such piety and savagery together. How that old fellow’s cruel small eyes did sparkle with native pleasure as the thick, pungent smoke of the sacrificial fire went roaring up, and the hiss and splutter half drowned the screaming of men and women pent in their wicker cages amid that blaze! Oh! Old Ufner liked the smell of hot new blood, and there was no music to his British ear like the wail of a captive’s anguish. And then for me to be pattering round his cell like this in the gusty dark midnight, shivering and alone, patting and feeling the mighty lid of that great crypt, and begging a friendly shelter in my stress and weariness of that ghostly hostelry—it was surely strange indeed.

Twice or thrice I walked round the great coffer—it was near as big as a herdsman’s cottage—and then, finding no other crack or cranny, stopped and stooped before the tiny portal at the lower end. I saw as I knelt that that tremendous slab was resting wondrous lightly on a single point of upright stone set just like the trigger of an urchin’s mouse-trap, but, nothing daunted, pushing and squeezing, in I crept, and felt with my hands all that I could not see.

The foxes and the weather had long since sent all there was of Ufner to dust. All was bare and smooth, while round the sides were solid, deep earth-planted slabs of rock—no one knew better than I how thick they were and heavy!—and on the floor a soft couch of withered leaves and grasses.

Now one more sentence, and the chapter is ended. I had not coiled myself down on those leaves a minute, my weary head had nodded but once upon my arm, my eyelids drooped but twice, when, with a soundless start, undermined by the fierce storm, and moved a fatal hair’s-breadth by my passage, the propping key-stone fell in, and all at once my giant roof began to slide. That vast and ponderous stone, that had taken two tribes to move, was slipping slowly down, and as it went, all along where it ground, a line of glowing lambent fire, a smoking hissing band of dust marked its silent, irresistible progress—a hissing belt of dust, and glow that shone for a half-moment round the fringe of that stupendous portal—and then, too late as I tottered to my weary knees, and extended a feeble hand toward the entrance, that mighty door came to a rest, that ponderous slab, that scarce a thousand men could move, fell with a hollow click three inches into the mortises of the earth-bound walls, and there in that mighty coffer I was locked—fast, deep, and safe!

I listened. Not a sound, not a breath of the storm without moved in that strange chamber. I stared about, and not one cranny of light broke the smooth velvet darkness. What mattered it? I was weary and tired—to-morrow I would shout and some one might hear, to-night I would rest; and, Jove! how deep and warm and pleasant was that leafy bed that chance had spread there on the floor for me!