CHAPTER XVII

I cannot say, distinctly, what roused me next morning. My faculties were all in a maze, my body cramped and stiff as old leather—no doubt due to the wetting of the previous evening, or my hard couch—while the darkness bewildered and numbed my mind. Yet, indeed, I awoke, and, after all, that was the great thing. I awoke and yawned, and feebly stretched my dry and aching arms—good heavens! how the pain did fly and shoot about them!—and rolled my stiff and rusty eyeballs, and twisted that pulsing neck that seemed in that first moment of returning life like a burning column of metal through which the hot river of my starting blood was surging in a hissing, molten stream. I stretched, and looked and listened as though my faculties were helpless prisoners behind my numb, useless senses; but, peer and crane forward as I would, nothing stirred the black stillness of my strange bed-chamber.

Nothing, did I say? Truly it was nothing for a time, and then I could have sworn, by all the rich repository of gods and saints that the wreck of twenty hierarchies had stranded in my mind, that I heard a real material sound, a click and rattle, like metal striking stone, this being followed immediately by a star of light somewhere in the mid black void in front. Fie! ’twas but a freak of fancy, the stretching of my cramped and aching sinews, but a nucleus of those swimming lights that mocked my still sleepy eyes! I covered them with my hands and groaned to be awake; I strove to make point or sense out of the wild flood of remembrance that ebbed and flooded in thunderous sequence through my head; and then again, obtrusive and clear, came the click! click! of the unseen metal, and the shine of the great white planet that burned in the black firmament of my prison behind it.

I staggered to my feet, stretching out eager hands in the void space to touch the walls, and tried to move; and, as I did so, my knees gave way beneath me; I made a wild grasp in the darkness, and fell in a loose heap upon the littered, dusty floor. Lord! how my joints did ache! how the hot, swift throes that monopolized my being shot here and there about my cramped and twitching limbs! I rolled upon the dust-dry earth of that gloomy chamber and cursed my last night’s wetting; cursed the salt-sea spray that could breed such fiery torments; and even sent to Hades my errand and my scrip of victory, the which, however, I was cheered to note, in its bronze case now and then, with a movement or a spasm of pain, knocked against my bare ribs as though to upbraid me as a laggard embassy for lying sleeping here while all men waked to know my tidings. I rose again, with rare difficulty but successfully this time, and peered and listened till the dancing colors in my eyes filled the empty air with giddy spinning suns and constellations, and the making tide of wakefulness, flooding the channels of my veins, cheated my ears to fancy some hideous storm was raging up above, and thunderbolts were tearing shrieking furrows down the trembling sides of mountains, and all the rivers of the world (so hideous was that shocking sound) were tumbling headlong in wild confusion into the void middle of the world.

I stuffed my ears and shut my eyes, and turned sick and faint at that infernal tumult. My head spun and throbbed, and my light feet felt the world give under them. I had nearly fallen, when once again, just as my spinning brain was growing numb, and the close, thin air of that place failed to answer to the needs of my new vitality, there came that click! click! again, and the blessed white star that followed it. This time that gleam of hope was broad and strong. On either side as it shone, white zigzag rays flew out and stood so written upon the black tablet of my prison. Ah! and a draught of nectar, of real, divine nectar, of sweet white country air, came in from that celestial puncture!

I leaped to it and knelt, and put my thirsty lips to that refulgence and drank the simple ambient air that came through, as though I were some thirsty pilgrim at a gushing stream. And it revived me, cooling the rising fever of my blood, and numbing, like the sweet sedative it was, the pains, that soon ran less keen and throbbed less strong, and, in a few more minutes, went gently away into the distance under its beneficent touch. Mayhap I fainted or slept for some little time, overwhelmed by the stress of those few waking moments. When I looked up again all was changed. I myself was new and fresh, and felt with every pulse the strong life beating firm and gentle within me; and my prison cell—it was no more a prison!

There was a gap bigger than my fist where the star had been, with great fissures marking the outline of one of the stones that had supported the topmost slab, and through the gap a peep of countryside, of yellow grass, and sapphire sea, of pearly waves lisping in summer playfulness around a golden shore, and overhead a sky of delightful blue.

I was grateful, and understood it all. The storm had gone down during the night and the sun had risen; these were good folk outside, who, by some chance, knew of my sheltering-place and had come early to release me—a happy chance indeed! And it was their strong blows and crowbars working on my massive walls that let in the light, and—none too soon—refreshed me with a draught of outer air. Fool that I was to let an uneasy night and a salt-sea soaking cloud my wit!

I was so pleased at the prospect of speedy release that I was on the point of calling out to cheer my lusty friends at their work and show the prisoner lived. But had I done so this book had never been written! That shout was all but uttered—my mouth was close to the orifice through which came the pleasant gleam of daylight, when voices of men outside speaking one to another fell upon my ear.

“By St. George,” I heard one fellow say, “and every fiend in hell! they who built this place surely meant it to last to Judgment! Here we have been heaving at it since near daylight and not moved a stone.”

“Ah! and if you stand gaping there,” chimed in another, “we’ll not have moved one by Tuesday week. On, you log! let’s see something of that strength you brag of—why, even now I saw a shine and twinkle in the opening there. This crib may prove the cradle of our fortunes, may make us richer men than any strutting sheriffs, and recompense us for a dozen disappointments! To it again; and you, Harry, stand ready with the wedges to put them in when we do lift.”

I pricked my ears at this, as you will guess, for there was no mention of me expectant, and only talk of wealth and recompense. I listened, and heard the sulky workman take again his crowbar. I heard him call for a drink, and the splash of the liquid into the leathern cup sounded wonderfully clear in my silent chamber; then, as though in no hurry to fall on, he asked, “What of the spoil we have already, mates? A sight of those baubles would greatly lighten our labor, I think.”

“Now, as I had a man for my father,” burst out the first speaker, “never did I see so small a heart in so big a body! Show him the swag, Harry! rattle it under his greedy nose! and when he has done gloating on it perhaps he’ll turn to and do something for a breakfast!”

At this there was a pause and a moving of feet, as though men were collecting round some common object. Then came the tinkle of metals, and, by Jove! I had not yet forgotten so much of merchant cunning in my soldiering but that I recognized the music of gold and silver over the base clink of lesser stuff. They tried, and sampled, and rung those wares over my head; and presently he who was best among them said:

“A very pretty haul, mates, and, wisely disposed of, enough to furnish us well, both inside and out, for a long time. These circlets here are silver, I take it, and will run into a sweet ingot in the smelting-pot. Yon boss is a brooch, by the pin, and of gold; though surely such a vile fashion was never forged since Shem’s hammer last went silent.”

“What, gold, sir!”

“Ah! what else, old bullet-costard? Dost thou think I come round and prize cursed devil-haunted mounds for lumps of clay? The brooch is gold, I say; and the least of these trinkets” (whereon there came a sound like one playing with bracelet and bangle)—“the worst of them white silver. To it, then, good fellows, again! Burst me this stony crypt, and, if it prove such a coffer as I have right to hope, before the day is an hour older, you shall down to yonder town and there get drunk past expectation and your happiest imaginings.”

So, my friends, I mused, ’tis not pure neighborliness that brings you thus early to my rescue! Never mind; many a good deed has been done in search of a sordid object, and whether you come for me or gold, it shall vantage me alike. I will lend a hand on my side, since it were a pity to keep this big fellow from his breakfast longer than need be.

While they plied spade and lever outside, I scraped below, and put in, as well as I was able, a stone wedge now and then, whenever their exertions canted the great stone a little to one side or the other. The interest of all this, and because I was never apt in deceit, made me somewhat reckless about showing too soon at the narrow opening, and presently there came a guttural cry above, and a sound as though some one had dropped a tool and sprung back.

“Hullo! stoutheart,” called the captain’s voice, “what now? Is it another swig of the flask you want to swell your shallow courage, or has thy puissant crowbar pierced through to hell?”

“Hell or not,” whined the fellow, “I do think the fiend himself is in there. I did but stoop on a sudden to peer within, and may I never empty a flagon again but there was something hideous moving in the crypt! something round and shaggy, that toiled as we toiled, and pushed and growled, and had two flaming yellow eyes——”

“Beast! coward! Oh, that I had brought a man instead of thee! ’Twas gold you saw—bright, shining metal—think, thou swine, of all it will buy, and how thou may’st hereafter wallow in thy foul delights! And wilt thou forego the stuff so near? Gods! I would have a wrestle for it though it were with the devil himself! Give me the crowbar.”

Apparently the captain’s avarice was of stouter kind than the yeoman’s, for soon after this the stone upright began to give, and I saw the moment of my deliverance was near. Now, I argued to myself, these gentlemen outside are obvious rogues, and will much rather crack me on the head than share their booty with such a strange-found claimant, hence I must be watchful. Of the two under-rogues I had small fear, but the captain seemed of bolder mold, and, unless his tongue lied, had some sort of heart within him. So I waited watchful, and before long a more than usually stalwart blow set the stone off its balance. It slipped and leaned, then fell headlong outward with a heavy thud, and, turning over on its side, rolled to the edge of the slope, and there, revolving quicker and more quickly, went rumbling and crashing down through the brambles into the valley a quarter of a mile below. As it fell outward, a blaze of daylight burst upon my prison, and, with a shout of joy, the foremost of the rogues dashed into my cell. At the same moment, with such an old British battle yell as those monoliths had not heard for a thousand years, but sorely dazed, I sprang forward. We met in mid career, and the big thief went floundering down. He was up again in a moment, and, yelling in his fear that the devil was certainly there, rushed forth—I close behind him—and infected his timorous comrade, and away they both went toward the woods, racing in step and screaming in tune, as though they had practised it together for half a lifetime. The fellows fled, but their leader stood, white and irresolute, as he well might be, yet made bold by greed; and for a moment we faced each other—he in his greasy townsman finery, a strong, sullen thief from bonnet to shoe, and I, grim, gaunt, and ragged, haggard, wild, unshorn, standing there for a moment against the black porch of the old Druid grave-place—and then, wiping the sunshine from my dazzled eyes and stooping low, I ran at him! Many were the ribbons and trinkets I had taken long ago at that game. I ran at him, and threw my arms round his leather-belted middle, and, with a good Saxon twist, tossed his heels fairly into the air and threw him full length over my shoulder. He fell behind me like a tree on the greensward, while his head striking the buttress of a stone stunned him, and he lay there bleeding and insensible.

“Hoth! good fellow,” I laughed, bending over him, “I am sorry for that headache you will have to-morrow, but before you challenge so freely to the wrestle you should know somewhat more of a foeman’s prowess!”

When I turned to the little heap of spoil the ravishers of the dead had gathered and laid out on a cloth upon the stones, at once my mood softened. There in that curious pile of trinkets were things so ancient and yet so fresh that I heaved a sigh as I bent over them, and a whiff of the old time came back—the jolly wild days when the world was young rose before me as I turned them tenderly one by one. There lay the bronze nobs from a British shield, and there, corroded and thin, the long, flat blade that my rugged comrades once could use so well. There was the broken haft of a wheel-scythe from a chief’s battle-car, and, near by, the green and dinted harness of a war-horse. Hoth! how it took me back! how it made me hear again in the lap of the soft Plantagenet sea and all the insipid sounds of this degenerate countryside the rattle and hum of the chariots as we raced to war, the sparkle and clatter of the captains galloping through the leafy British woods, and then the shout and tumult as we wheeled into line in the open, and, our loose reins on the stallions’ necks and our trembling javelins quivering in our ready hands, swept down upon the ranks of the reeling foeman!

There again, in more peaceful wise, was a shoulder-brooch some British maid had worn, and the wristlet and rings of some red-haired Helen of an unfamous Troy. There lay a few links of the neck-chains of a dust-dead warrior, and there, again, the head of his boar-spear. Here was the thin gold circlet he had on his finger, the rude pin of brass that fastened his colored cloak and the buckle of his sandal. Jove! I could nearly tell the names of the vanished wearers, I knew all these things so well!

But it was no use hanging over the pile like this. The ruffian I had felled was beginning to move, and it served no purpose to remain: therefore—and muttering to myself that I was a nearer heir to the treasure than any among those thieves—I selected some dozen of the fairest, most valuable trinkets, and put them in my wallet. Then, feeling cold—for the fresh morning air was thin and cool here, above the sea—the best coat from the ragged pile the rogues had thrown aside, to be the lighter at their work, was chosen, and, with this on my back, and a stout stave in my hand, I turned to go. But ere I went I took a last look round—as was only natural—at a place that had given me such timely shelter overnight. It was strange, very strange; but my surroundings, as I saw them in the white daylight, matched wondrous poorly with my remembrance of the evening before! The sea, to begin with, seemed much farther off than it had done in the darkness. I have said that when I swam ashore my well-remembered British harbor had, to my eyes, silted up wofully, so that the knoll on which Blodwen’s stockades once stood was some way up the valley. But small as the estuary had shrunk last night, I had, it seemed, but poorly estimated its shrinkage. ’Twas lesser than ever this morning, and some kine were grazing among the yellow kingcups on the marshy flats at that very place where I could have sworn I came ashore on the top of a sturdy breaker! The greedy green and golden land was cozening the blue channel sea out of beach and foreshore under my very eyes; the meadow-larks were playing where the white surf should have been, and tall fern and mallow flaunted victorious in the breeze where ancient British keels had never even grated on a sandy bottom. I could not make it out, and turned to look at the tomb from which I had crept. Here, too, the turmoil of yestere’en and my sick and weary head had cheated me. In the gloom the pile had appeared a bare and lichened heap washed out from its old mound by rains: but, Jove! it seemed it was not so. I rubbed my eyes and pulled my peaked beard and stared about me, for the crypt was a grassy mound again, with one black gap framed by a few rugged stones jutting from the green, as though the slope above it had slipped down at that leveler Nature’s prompting, and piled up earth and rubbish against the rocks, had escaladed them and marched triumphant up the green glacis, planting her conquering pennons of bracken and bramble, mild daisy and nodding foxglove, on that very arch where, by all the gods! I thought last night the withering lightning would have glanced harmless from a smooth and lichened surface. Well, it only showed how weary I had been; so, shouldering my cudgel, and with a last sigh cast back to that pregnant heap of rusty metal, I turned, and with fair heart, but somewhat shaky limbs, marched off inland to give my wondrous news.

How pleasant and fair the country was, and after those hot scenes of battle, the noise and sheen of which still floated confusedly in my head, how sweetly peaceful! I trod the green, secluded country lanes with wondrous pleasure, remembering the bare French campagnas, and stood stock-still at every gap in the blooming hedges to drink the sweet breath of morning, coming, golden-laden with sunshine and the breath of flowers, over the rippling meadow-grass! In truth, I was more English than I had thought, my step was more elastic to tread these dear domestic leas, and my spirits rose with every mile simply to know I was in England! And I—a tough, stern soldier, with arms still red to the elbow in the horrid dye of war, and on a hasty errand, pulled me a flowering spray from the coppices, and smiled and sang as I went along, now stopping in delighted trance to hear out the nightingale that, from a bramble athwart the thicket path, sang most enrapturedly, and then, forgetful of my haste, standing amazed under the flushed satin of the blooming apples. “Jove!” I laughed, “here is a sweeter pavilion than any victor prince doth sleep in! Fie! to fight and bleed as we do yonder, while the sweetness of such a tent as this goes all to waste upon the wind!” and I sat and stared and laughed until the prick of conscience stirred me and, reluctant, I passed on again. Then over a flowery mead or two, where the banded bees swung in busy fashion at the lilac cuckoo-flowers, and the shining dewdrops were charged with a hundred hues, down to a sunny, babbling brook that sparkled by a yellow ford. There I would stand and watch the silver fingers of the stream toy and tug the great heads of nodding kingcup, watch the flash of the new-come swallow’s wing, as he shot through the byways between the mallows, and be so still that e’en the timid water-hen led out her brood across the freckled play of sunshine on the water, and the mute kingfisher came to the broken rail and did not fear me. “Surely a happy stream,” I thought, “not to divide two princely neighbors! What a blessed current that can keep its native color and chatter thus of flowers and sunshine, while yon other torrent runs incarnadine to the sea—a corpse-choked sewer of red ambition!”

Then it was a homestead that, all unseen, I paused by, watching the great sleek kine knee-deep in the scented yellow straw, the spangled cock defiant on the wall, the tender doves a-wooing on the roof-ridge, and presently the swart herdsman, with flail and goad, come out from beneath his roses and stoop and kiss the pouting cherry lips of the sweet babe his comely mate held up to him. “Jove!” I meditated, “and here’s a goodly kingdom. Oh that I had a realm with no politics in it but such as he has!” and so musing I went along from path to path and hill to hill.

At one time my feet were turned to a way-side rest-house, where a jug of wine was asked for and a loaf of bread, for you will remember that saving a handful of dry biscuit, which I broke in my gauntlet palm and ate between two charges, I had not broken fast since the morning before Crecy. The master of the tavern took up the coin I tendered and eyed it critically. He held it in the sun, and rung it on a stone and spat upon it, then, taking a little dust from the road, rubbed diligently until he came down through the green sea-slime to the metal below. It was true-coined, plump, and full, though certainly a trifle rusty; and this and my grim, commanding figure in his doorway carried the day. He brought me wine and cheese and bread, whereon I sat on a corner of the trestle table munching them outside in the sun under shadow of my broad felt yokel hat, with the quaint inn sign gently creaking overhead, and my moldy, sea-stained legs dangling under me.

I was in a good mood, yet thoughtful somehow, for had not the King especially warned me not to part lightly with the precious news wherewith I was freighted? And if so be that I must be reticent in this particular, yet again my heart was surely too full of my victorious errand to let me gossip lightly on trivial matters; thus my bread was broken in abstracted silence, and, when my beaker went now and again into the shade of my hat-brim, I drank mutely and proffered no sign of friendship to those other country wayfarers who stood about the honeysuckled doorway eyeing me askance after the manner I was so used to, and whispering now and then to one another.

I sat and thought how my errand was to be most speedily carried out, for you see I might trudge days and days afoot like this before good luck or my own limbs brought me to the footstool of Edward’s Royal wife, and gave me leave to burst that green and rusty case that, with its precious scroll, still dangled at my side. I had no money to buy a horse—the bangles taken from the crypt-thieves would not stand against the value of the boniest palfrey that ever ambled between a tinker’s legs—and last night’s infernal wetting had made me into the sorriest, most moldy-looking herald that ever did a kingly bidding. Surely, I thought, as I glanced at my borrowed clay-stained rustic cloak, my cracked and rotten leather doublet, my tarnished hose all frayed and colorless, my shoon, that only held together, methought, by their patching of gray sea-slime and mud, surely no one will lend or loan me anything like this; they will laugh at my knightly gage of honorable return, and scout the faintest whisper of my errand!

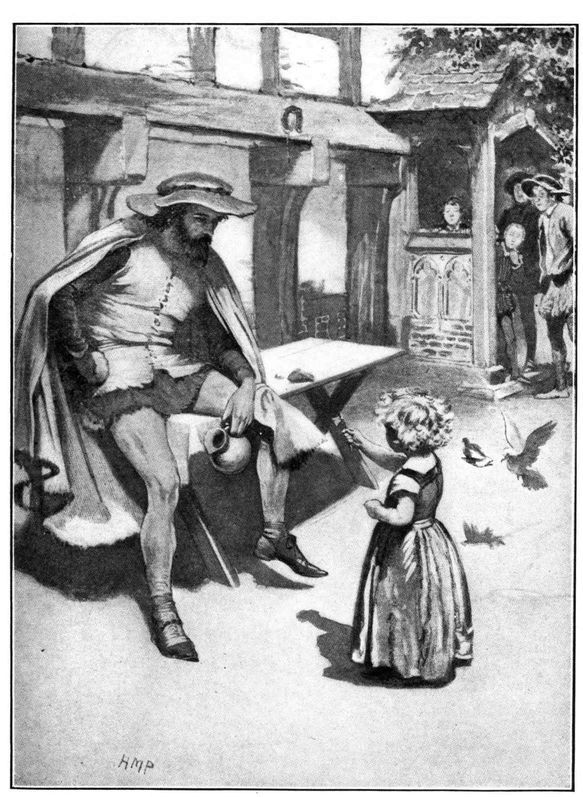

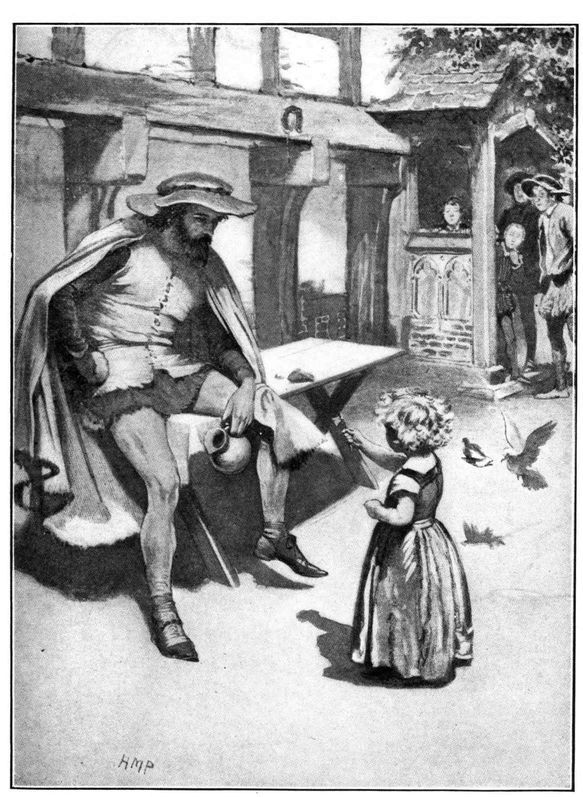

Thus ruefully reflecting, I had finished my frugal luncheon, yet still scarce knew what to do, and maybe I had sat dubious like that on the trestle edge for near an hour, when, looking up on a sudden, there was a blooming little maid of some three tender years standing in the sun staring hard upon me, her fair blue eyes ashine with wonder, and the strands of her golden hair lifting on the breeze like gossamers in June. She had in one rosebud hand a flower of yellow daffodil, and in fault of better introduction proffered it to me. My stern soldier heart was melted by that maid. I took her flower and put it in my belt, and lifted the little one on my knee, then asked her why she had looked so hard at the stranger.

She proffered it to me

“Oh!” she said, pointing to where some older children were watching all this from a safe distance, “Johnnie and Andrew, my brothers, said you were surely the devil, and, as they feared, I came myself to see if it were true.”

“And am I? Is it true?”

“I do not know,” said the little damsel, fixing her clear blue eyes upon mine—“I do not know for certain, but I like you! I am sorry for you, because you are so dirty. If you were cleaner I could love you”—and very cautiously, watching my eyes the while, the pretty babe put out a petal-soft hand and stroked my grim and weathered face.

I could not withstand such gentle blandishment, and forgot all my musings and my haste, and kissed those pink fingers under the shadow of my hat, and laid myself out to win that soft little heart, and won it, so that, when presently the wondering mother came to claim her own, the little maiden burst into such a headlong shower of silver April tears that I had to perjure myself with false promises to come again, and even the gift of my last coin and another kiss or two scarce set me free from the sweet investigator.

But now I was aroused, and stalked down the green country road full of speed and good intention. I would walk to the Royal city, since there were no other way, and these fair shires must have grown expansive since the olden days if I could not see a march or two while the sun was up. Eastward and north I knew the Court should lie, so bent my steps through glades and commons with the midday sun behind my better shoulder. But the journey was to be shorter than seemed likely at the outset. After asking, to no purpose, my road of several rustics, a venerable wayfarer was chanced upon, ambling down a shady gully.

This quaint old fellow sat a rough little steed, one, indeed, of the poorest-looking, most knock-kneed beasts I had ever seen a gentleman of gentle quality astride of. And, in truth, the rider was not better kept. He wore a great widespreading cloak of threadbare stuff, falling from his shoulders to his knees in such ample folds that it half hid the neck and quarters of his steed. Below this mantle, splashed with twenty shades of mud and most quaintly patched, you saw the pricks of rusty iron spurs on old and shabby leather boots, and just the point of a frayed black leather scabbard peeping under his stirrup-straps. The hat he wore was broad-brimmed and peaked, and looked near as old as did its wearer. Under that shapeless cover was a most strange face. I do not think I ever saw so much and various writ upon so little parchment as shone upon the dry and wrinkled surface of that rider’s features. There were cunning and closeness on it, and yet they did not altogether hide the openness of gentle birth and liberal thought. Now you would think to watch those shrewd, keen eyes a-glitter there under the penthouse of his shaggy eyebrows, he was some paltry trader with a vision bounded by his weekly till and the infruct of his lying measures, and then anon, at some word or passing fancy, as you came to know him better, ’twas strange to see how eagle-like those optics shone, and with what a clear, bright, prophetic gaze the old fellow would stare, like a steersman through the dim-lit gloom of a starry night, over the wide horizon of the visionary and uncertain! He could look as small and mean about the mouth as a usurer on settling day; and then, when his mood changed, and he fell thoughtful, the gentle melancholy of his face—the goodly soul that spoke behind that changeful mask, the strange dissatisfaction, the incompleteness, the unhappy longing for something unattainable there reflected, made you sad to look upon it!

I overtook this quaint rider as he rode alone, my active feet being more than a match for the shaky limbs of that mean beast he sat upon, and, coming alongside, observed him unnoticed for a minute. Truly as quaint a fellow-traveler as you could meet! His head was sunk, and his grizzled white beard fell over his chest: his eyes were fixed in vacant stare on some vision of the future; and his lips moved tremulously now and again as the thoughts of his mind escaped unheeded from between them. Was he poet? Was he seer? Was it a black past or a red, rosy future the old fellow babbled of? Jove! I was not in very good kind myself, and I fancy I had read now and again, in the wonder of those who saw me, that my face had a tale to tell. But, by the great gods! I was neat and pretty-pied beside this most rusty gentleman; my face was as void as a curd-fed bumpkin’s, compared to those eloquently absent eyes, that fine, mean profile, there, in the slouch of the big hat, and those busy lips!

“Good-morning, Sir!” I said; and as the old man looked up with a start and saw me, a stranger, walking by his side, all the fervor and the fancy died from off his face, the fine features shut upon themselves; and there he was, the meanest, shallowest, most paltry-looking of old rogues that had ever pulled off a cap to his equal!

He returned my first light questionings with a sullen suspicion, which gradually thawed, however, as his keen scrutiny took, apparently, reassuring stock of my face and figure, and we spoke, as fellow-travelers will, for a few moments on the roads, the weather, and the prospect of the skies. Then I asked him, with small expectation of much advantage in his answer, “which was the best way to Court.”

“There are many ways, my son,” he said. “You may get there because of extreme virtue, or on the introduction of peculiar wickedness.”

“Ah! but I meant otherwise——”

“Shining wisdom, they say, brings a man to Court—or should. And, God knows, there is no place like Court for folly! If thou art very beautiful thou may come to it, and if thou art as ugly as hell they will have thee for a laughing-stock and nine-days’ wonder. Anaximander went to Court because he was so wise, and Anaxippus because he was so foolish; Diphilus because he was so slow in penmanship, and Antimachus because he wrote so much and swift. Ah, friend! many are the ways. Polypemon lived by plunder, and, because he was the cruelest thief that ever stripped a wanderer by green Cephisus, he came under the notice of kings and gods; ay, and Clytius is famous because he was so faithful; and the patriotic Codrus because he bared his bosom to the foe, and Spendius for a hundred treacheries, and——”

“No! no!” I cried, “no more, Sir, I entreat. I did not mean to play footpad to thy capacious memory, and rob your mind of all these just comparisons, but only to ask, in ordinary material manner, which was the best way to the palace, which the nearest road, the safest footpath for a hasty stranger to our good Queen’s footstool. I have a Royal script to deliver to her.”

“What, is it the Queen you want to see? Why, I am bound that road myself, and in a few minutes I will show you the pennons glancing among the trees where they be camped.”

“Where they be camped?” I exclaimed in wonder. “I thought that was many a mile from here—in fact, Sir, in the great city itself, and yet you say a few minutes will show us the Royal tents.”

“Oh, what a blessed thing are youthful legs! And were you off to distant Westminster like that, good fellow, ‘to see the Queen,’ forsooth, with nothing in thy wallet, and as little in thy head?” And the old man eyed me under his slouching cap with a mixture of derision and strange curiosity.

“I tell you, Sir,” I answered, “I come on hasty business; I am a messenger of the utmost urgency, and if I am afoot instead of mounted it is more misfortune than inclination. What brings the Queen, if, indeed, we are so near her, thus far afield?”

“Praise Heaven, young man, there is no one who knows less of the goings and comings of her and hers than I do. I hate them,” he said sourly; “a lying swarm of locusts round that yellow jade they call a Queen—a shallow, cruel, worthless crew who stand in the way of light and learning, and laugh the poor scholar out of face and heart!” And, muttering to himself, my companion relapsed into a moody silence as we breasted the last rise. But on a sudden he looked up with something like a smile wrinkling his withered cheek, and went on: “But you do not laugh—you have some bowels of compunction within you—you can be as civil to a threadbare cloak as to a silken doublet. Gads! fellow, there is something about thee that moves me very strangely. Art thou of gentle quality?”

“I have been of many qualities in my time, Sir.”

“So I guessed, and something tells me we shall see more of one another. There is a presence about thee that makes me fear—that puts a dread upon me, why I know not. And then, again, I feel drawn to thee by a strong, strange sense, as the Persian says one planet is drawn toward another.”

I let the old fellow ramble on, paying, indeed, but cold notice to his chatter, since all my thoughts were on ahead, and when at last we came out of the hazel dingles, there, sure enough, down in the valley was a white road winding among the trees, and a stately park, a goodly house of many windows, and amid the fair meadows among the branches shone the white gleam of tents, and overhead the flutter of silken tags and gonfalons, and now and then there came the glint of steel and gold from out that goodly show, and the blare of trumpets, and more softly on the afternoon air the shout of busy marshals, the neighing of steeds, and the low murmur of many voices.

Oh, it was a pretty scene to see the tender countryside so fresh and green, and the rolling meadows at our feet dusted thick with gold and silver flowers all blended in a splendid web of tissue under the shining sun. And there the flush of blossom on the orchards streaked the fair valley like a sunset cloud, and here the bronze of budding oaks lay soft in the hollows, while overhead the blue canopy of the sky was one unbroken roof from verge to verge.

We two looked down upon that scene of peace with different feeling for a space, then, making my friendly salutation to the dreamy pedant, “Here, Sir,” I said, “I fear we part forever.”

“Not so,” he said: “we shall meet once more, and soon.”

“Well! well! Soon or distant, we will meet again in friendship,” and, with a wave of the hand, off I set, delighted to think chance had so favored me, and all impatient to tell my news. I did not stop to look to left or right, but down the glen I ran into the valley, scaring the frightened sheep and oxen, and stopping not for fence or boundary until the broad road was reached, and all among the groups of gaping countrymen and busy lackeys leading out the steeds to water in the meadows round the Royal camp, I slackened my pace. The broad park gates were open, and inside, amid the oak-trees around the great house, gay confusion reigned. There, on one hand, were the fair white tents bright with silk and golden trappings, and, while a hundred sturdy yeomen were busy setting up these cool pavilions, others spread costly rugs about their porches, and displayed within them lordly furniture enough to dazzle such rough soldier eyes as mine. There in long rows beneath the branches were ranked a wondrous show of mighty gilded coaches with empty shafts a-trail, all still dusty from the road, and hurrying grooms were covering these over for the night, while others fed and tended a squadron of sleek, fat horses, whose beribboned manes and glistening hides so well filled out struck me amazed when I recalled those poor, ragged, muddy chargers whereon we had borne down the hosts of Philip’s chivalry two days before. All about the green were groups of gallant gentlemen and ladies, and I overheard, as I brushed by, some of them speaking of a splendid show to be given that night in the court of the great house near by, and how the proud owner of it, thus honored by the great Queen’s presence, had beggared him and his for many a day in making preparation. It was most probable, for the white-haired seneschal was tearing his snowy locks, entreating, imploring, amid a surging, unruly mass of porters, cooks, and scullions, while heaps of provender, vats of wine, and mighty piles of food for men and horses, littered all the rearward avenues.

But little I looked at all these things. Clad like many another countryman come there to see the show (only a little more ragged and uncouth), I passed the outer wickets, and, skirting the groups of idlers, strode boldly out across the trim inner lawns and breasted the wide sweep of steps that led to the great scutcheoned doorway. All down these steps gilded fellows were lolling in splendid finery, who started up and stared at me, as, nothing noticing their gentle presence, now hot upon my errand, I bounded by. At top were two strong yeomen, gay in crimson and black livery, of most quaint kind, with rampant lions worked in gold upon their breasts, and tall, broad-bladed halberds in their hands. They made a show of barring the way with those mighty weapons; but I came so unexpected, and showed so little hesitation, they faltered. Also, I had pulled off my cap, and better men than they had stepped back in fear and wonder from a glance of that grim, stern face that I thus did show them. Past these, and once inside, I found the Queen was receiving the country-folk, and up the waiting avenue of these good rustic lieges I pushed, brushing through the feeble fence of stewards’ marshaling-rods held out to awe, and, nothing noticing a score of curly pages who threw themselves before me, I burst into the presence chamber. Hoth! ’Twas a fine room, like the mid-aisle of a great cathedral, and all around the walls were banners and bannerets, antlers of deer, and goodly shows of weapons, and suits of mail and harness. And this splendid lobby was thronged with courtiers in silks and satins, while ruffs and stocks and mighty collarets, and pearls and gems, and cloth of gold and sarsanet glittered everywhere, and a gentle incense of lovely scents mingled with a murmur of courtly talk went up to the fair carved oaken ceiling. Right ahead of me was a splendid crimson carpet of wondrous pile and softness, and at the far end of that stately way a daïs, and on it, lightly chatting amid a pause in the Royal business—the Queen!

She was not the least what I had looked for. I had pictured Edward’s noble dame, the daughter of the knightly house of Hainault, as pale and proud and dark—the fit wife to her warlike husband, and a meet mother to her son. But this one was lank and yellow, comely enough no doubt and tall, with a mighty proud light in her eyes when occasion served, and a right royal bearing, yet still somehow not quite that which I expected. What did it matter? Was it not the Queen, and was not that enough? Gods! What should it count what color was her hair, since my master found it good enough? And, in truth, but I had something to say would bring the red into those lackluster cheeks, or Philippa were unlike all other women. Therefore, with a shout of triumph that shocked the mild courtiers, brandishing my precious script above my head, I leaped forward, and, dashing up that open crimson road, ran straight to the footstool of the Royal lady, and there dropping on one knee:

“Hail! Royal mother,” I cried.

“Thanks!” she said sardonically, as soon as she regained her composure. “Thanks, gentle maid!”

“Madam,” I cried, “I come, a herald, charged with splendid news of conquest! But one day since, over in famous France, thy loyal English troops have won such a victory against mighty odds as lends a new luster even to the broad page of English valor. But one day since, in your noble General’s tent——”

But by this time all the throng of courtiers had found their tongues, and some certain quantity of those senses whereof my sudden entry had bereft them. While a few, who caught the meaning of my word, and, stopping not to argue, thought it was the news indeed of a victory that glittering Court had long hoped for, broke out into tumultuous cheering—waving scarf and handkerchief, and throwing wide the lattices, that the common folk without might share their noisy joy, those others who stood closer around, and saw my ragged habiliments, could not believe it.

“You a herald!” exclaimed one grizzled veteran in slashed black velvet over pearly satin. “You a messenger chosen for such an errand! Madam,” he cried, drawing out a long rapier from its velvet case, “it is some madman, some brain-sick soldier. I do implore your Grace to let me call the guards.”

“An assassin! an assassin!” cried another. “Run him through, Lord Fodringham! Give him no chance or parley!”

“’Tis past belief!” exclaimed a dainty fellow, all perfumed lace and golden chains. “Such glad tidings are not trusted to base country curs.”

“A fool!” “A rogue!” “A graceless villain!” they shouted. “Stab him! drag him from the presence! Fie upon the billmen to let such scullions in upon us!” And thick these pretty peers came clustering on me, the while their ladies screamed, and all was stormy tumult.

Up, then, I jumped to my feet, and hot and wrathful, shaking my clenched fist in the faces of those glittering lords, broke out: “By the bright light of day, Sirs, he who says I have a better here in this hall, lies—lies loud and flatly. Do you think, because I come clad like this, you may safely spend your shallow wit upon me? I tell you all, pretty silken spaniels that you are! you, Fodringham, with the gilded toothpick you miscall a sword! you there, Sir, who reek of musk and valor! and all you others, who keep so discreetly out of arm’s reach!—I tell you every one that, in court or camp, in tilt or tourney, I am your mate! Ah, Sirs, and this rusty country smock, blazoned by miry ways and hasty travel; this muddy tabard here, because ’tis upon a herald’s breast, is more honorable wear than any silken surtout that you boast of. Gods, gentlemen! if so there be that any one here in truth misdoubts it, let me entreat his patience; let me humbly crave the boon that he will hold his mettled valor in curb just so long as I may render that message which I surely have at this Royal footstool, and then, on horse or foot, with mace or sword, I will show him my credentials!” But none of that glittering throng had aught to say. Those bold, silken lordlings pushed back in a wide circle from where I stood, fierce and tall in my muddy rags, and fumbled their golden dagger-knobs, and studied with drooped heads the dainty silk rosettes upon their cork-heeled shoes.

After waiting a moment, to give their valor fair chance of answering, I turned disdainfully from them, and, bending again to fair Queen Philippa, “Madam,” I said, “these noisy boys make me forget the smooth reverence that I owe your Grace, yet surely the noble daughter of Hainault will forgive a hasty word spoken in defense of soldier honor?”

“I know nothing, good fellow,” replied the Queen, eyeing her discomfited nobles with inward glee, “of thy Hainault, but I like thy outspokenness extremely. By Heaven! you make me think it was some time since I last saw a man about me.”

“And have I leave to do my mission, noble lady?”

“Ay, Sir, to it at once! We care not how you come, or who you are, or for the exact condition of your smock, so that you bring news of victory.”

“But, Madam,” put in Fodringham, “it is not safe—he has some desperate purpose——”

“Silence!” shouted the Queen, springing to her feet and stamping a pretty foot, cased in a dainty pearl-encrusted slipper—“silence, I say, Lord Fodringham, and all you other peers who make our presence-chamber like a bear-pit: silence! or by my father’s heart I will cure him of insolence who speaks again for once and all.” And the sallow virago, flushing like an angry yellow sunset, with her fierce gray eyes agleam, and her thin lips stern-set, one white hand clutching the high carved arm of her daïs, and the other set like white ivory on the jeweled handle of her fan, scowled round upon her courtiers.

They knew that proud termagant too well to meet her eye, and having stared them all into meek silence she let the yellow flush die from her cheek, and turning to me she said: “Now, fellow, to thy errand.”

“Then, sovereign lady,” I began, “but two days since, in France, the English troops, fair set upon a sunny hillside, were attacked by a vast array of foemen, and thanks to happy chance, to thy princely General’s captainship, and to the incredible valor of thy lieges, they were victorious!”

“Now may the dear God who rules these things accept my grateful and most humble thanks!” And the proud Queen, with bright moisture in her eye, looked skyward for a moment, and was so moved with true joy and pleasure in her country’s conquest that thereon at once she went up most mightily in my esteem.

“Most welcome of all heralds,” she went on, “how fared the English leader in that desperate fight? If aught has happed to Lord Leicester, it will spoil all else that you can say.”[4]

I did not quite catch the name she mentioned under breath, but I thought it was the Royal mother asking how my noble young master had prospered, so I spoke out at once.

“Madam, he is unhurt and well! It is not for me, a humble knight, to praise that shining star of honor, but he for whom thou art so naturally solicitous” (here the Queen blushed a little and looked down, while there was a scarce-suppressed laugh among the fair damsels behind me), “he, Madam, has done splendid deeds of valor. Three times, noble Queen, right along the glittering front of France he charged, three times he pierced so deep into that sea of steel that he near lay hands upon their golden lilies in mid-host. The proud Count of Poligny fell before him, and the Lord of Lusigny was overthrown in single combat; Besançon and Arnay went down under his maiden spear; he pulled an ancient crest from the Bohemian eagle in mid-battle. In brief, Madam, a more valorous knight was never buckled into armor; he was the prop and pillar of our host, and to him this victory is as largely due as it is to any.”

“Herald,” said the Queen, with real gratitude and pleasure in her voice again, “indeed your news is welcome. There was nothing I had rather than such a victory, and because ’tis his, because it will stifle the envious clamor of his enemies, and embolden me to do that which I hope to. Oh! your news fills up to overflowing the measure of my joy and satisfaction!” And the fair lady bent her head and fell into a reverie, like a maid who cogitates upon the prowess of an absent lover.

So far the woman—then the Queen came back, and lifting her shapely head, with its high-piled yellow hair, laced with strings of amethyst and pearl, and well set off by the great stiff-starched ruff behind, she asked:

“And my dear English nobles, and my stout halberdiers and pikemen—God forgive me that I should forget them!—how told the fight upon them? My heart bleeds to think of the odds you say they did withstand.”

“Be comforted, fair Sovereign! The tide of war set strong against our enemies, our palisades and trenches were well laid; the keen English arrows carried disaster far afield on their iron points ere the battle joined; the great host of France fell by its own mightiness; and victory, this time at least, shall wring but few tears from English maids or matrons.”

“Heaven be truly thanked for that!”

“Indeed, Madam”—so I went on—“none of great account fell those few hours since. Lord Harcourt I saw bear him like the bold soldier that he was, and when the battle faded into evening he it was who marshaled our scattered ranks and set the order for the night.”

“Who did you say?”

“Harcourt, lady, thy bold captain. And Codrington, too, was redoubtable, and came safe from the fight. Chandos dealt out death to all who crossed his path, like an avenging fury, yet took no scratch. Hot Lord Walsingham swept like an avalanche in spring through the close-packed Frenchmen, yet lives to tell of it, and old Sir John Fitzherbert, when I left the field—his white beard all athwart his shredded broken armor—was cheering loudly for our victory, the while they lapped him up in linens, for a French axe had shorn his left arm off at the shoulder. All have taken dints, but near all are safe and well.”

“’Tis strange,” said the Queen, thoughtfully, “’tis strange I know so few of these. I have a Harcourt, but he is not warlike; and cunning, cruel Walsingham lives in the north, and sits better astride of a dinner-stool than a charger. Codrington and Fitzherbert leading my troops to war! Here, let me see thy script: it may explain.” And she held out her jeweled hand.

Thereon a strange uneasiness possessed me, and seemed to cloud my honest courage. What was it? What had I to fear? I did not know. And yet my strong fingers, that never wearied upon a hilt though the day were ne’er so long, trembled as I slung round my pouch, and my heart set off a-beating with craven fear, as it had never beat before in sack or mêlée. It was too foolish; and, a little angry at the blood that ran so slowly in my veins, and the heavy sense of evil that sat on me all of a sudden, I pulled the metal letter-case from my wallet, and burst the seal and pressed the lid. The wallet split from side to side as though the stout leather were frail paper, and the strong metal crumbled in my fingers like red, rotten touchwood.

I stared at it in amazement. What could it mean? Then shook the thin, rusty fragments from my hand, and, putting on a bold face I did not feel, drew out the parchment from the strangely frail casing, brushed off the dust and litter, and handed it to the Sovereign.

“Lady,” I said in a voice I fain would have made true and clear, “there is the full account, and though seas have stained it, and rough travel spoiled the casing, as you saw, yet have I made all diligence I could. It was yesterday morning King Edward gave me that, and ‘Take it,’ he said, ‘as fast as foot can go to sweet Queen Philippa, my wife. Say ’twas penned on battlefield, and comes full charged with my dear and best affections.’ Thus, Madam, have I brought it straight to thee from famous Crecy, and here place it, the warrant of my truth, in Queen Philippa’s own hand.” And then I gave her the scroll.

Jove! how yellow and tarnished it did look! The frail silk that bound it was all afray and colorless; and the King’s great seal, that once had been so cherry-red, was bleached to sickly pallor! The Queen took it, and while I held my breath in nameless terror she turned it over and slowly round about, and stared first at me, and then at that fatal thing. She begged a dagger from a courtier at her side, and split the binding, and unfolded that tawny scroll that crackled in her fingers, it was so old and stiff, and read the address and superscription; and then, all on a sudden, while a deathlike silence held the room, she turned her stern, cold eyes, full of wrath and wonder, to me kneeling there, and burst out:

“Why, fellow! what mummery is all this? Philippa and Crecy? Why, thou incredible fool! Philippa of Hainault has been dust these twenty generations; and Crecy—thy ‘famous Crecy’—was fought near three hundred years ago! I am Elizabeth Tudor!”

Slowly I rose from my feet and stared at her—stared at her in the hush of that wondering room, while a cold chill of fear and consternation crept over my body. Incredible! “Crecy fought three hundred years ago!”—the hall seemed full of that horrible whisper, and a score of echoes repeated, “Queen Philippa has been dust these twenty generations, and Crecy—thy famous Crecy—was fought near three hundred years ago!” Oh, impossible—cruel—ridiculous!—and yet—and yet! There, as I stood, glaring at the Queen with strained, set face, and clenched hands, and heaving breath, gasping, wondering, waiting for something to break that hideous silence or give the lie to that accursed sentence that still floated round on the ambient air, and took new strength from the disdainful light in those clustering courtier eyes, and their mocking, scornful smiles—while I waited I remembered—by all the infernal powers I remembered—my awakening, and all the things I should have noted and had not. I recalled the bitter throes that had wracked my stiff joints in the old British grave as never mortal rheums yet twisted common sinew and muscle. I recalled the long labor of the crypt thieves, and the altered face of rocks and foreshore when my eyes first lit upon them after that long sleep. The very April season that sorted so ill with the August Crecy left behind took new meaning to me now all on an instant; and my ragged, crumbling raiment, in shreds and tatters, so ruinous as never salt spray yet made a good suit in one mortal evening, the strange garb and speech of those I met, and then this tawny, handsome, yellow lioness on the throne where should have been a pale, black Norman girl. Oh! hell and fiends! But she spoke the truth. I had lain three hundred years in Ufner’s stones, and with a wild, fierce cry of shame and anger, one long yell of pain and disappointment, I tore the cursed wallet from my neck and hurled it down there savagely at her feet, and turned and fled! Past the startled courtiers—past the screaming groups of laced and ruffled women—out! out! through the long line of feeble wardens; out between the glistening lowered halberds of the guards, down the white shining steps, an outcast and a scoffing-point, down into the road I ran, under a thousand wondering eyes, as fast as foot could go—not looking where or how, but seeking only the friendly cover of solitude and the fast-coming evening, and then, at length, worn out and spent—so sick in mind and heart I could scarce put one limb before another, I sank down on a grassy bank, a mile out of sight and sound of that fatal camp, and dropped my head into my hands and let the fierce despair and the black, swelling loneliness well up in my choked and aching heart.