CHAPTER XIX

I slept all that night a deep, unbroken slumber, waking with the first glimpse of morning, calm and refreshed, but very sleepily perplexed at my surroundings. It was only after long cogitations that the thread of my coming hither took form and shape. When at last I had examined myself in my antecedents, and reduced them to the melancholy present, I got up and looked from the window. A fair tract of country lay outside, deep-wooded and undulating, with pastoral meadows in between the hangers, and beyond, in the open, that streamlet whose prattle had been heard the night before lay spread into a broad, rushy tarn overgrown with green weeds and water things, and then running on through the flat soft meadows of this hollow where the house was built wound into the far distance, where it joined something that shone in the low white light like the gleam of a broader river. It was not a cheerful morning, for it had rained much, and the chilly mist hung low and still about these somber-wooded thickets, and the long grass between them; the sleepy rooks in the nests upon the bare treetops were later to wing than usual, cawing melancholy from the sodden boughs as though loth to leave them; and down below nothing sang or moved but the dark black merle fluttering along the covert side, and the mavis tuning a plaintive and uncertain note from off the wet fir-tops.

When I had stared my full, and learned little from the outlook, I donned those clothes that I had borrowed, and they were a happy choice. They fitted me like a lady’s glove, and, as I laced and hooked and belted them before a yellow mirror let into the black panel of my chamber door, I could not but feel they looked a goodly fashion for one of my make and build. I had not seemed so stalwart and so sleek, so straight in limb and broad in shoulder, since I was a Saxon thane. Then I belted on that pretty sword round my nicely tapering middle, and ran my fingers through my black Eastern locks, arranging them trimly inside my high-standing frill, and took another look or two into the glass, and then with a derisive smile—a little scornful at the secret pleasure those fine feathers gave me—I went forth.

Surely never did mortal mason build such a house before! The deepest, densest forest path that ever my hunter’s foot had trodden was simple to those mazes of curly stairs and dim passages and wooden alleys that led by tedious ways to nothing, and creaking, rotten steps that beguiled the wanderer by sinuous repetitions from desolate wing to wing and flight to flight. And all the time that I wrestled with those labyrinthine mazes in the struggle to reach latitudes I knew, not a sign could I see of my host, not a whisper could I catch of human voice or familiar sound in that dusty, desolate wilderness. Such an impenetrable stagnation hung over that empty habitation that the crow of a distant cock or the yelp of a village cur would have been a blessed interruption, but neither broke the vault-like, solemn stillness. From room to room I went, opening countless doors at random, all leading into spacious, moldy chambers, bare and tenantless, feeling my way by damp, neglected wall and dangerous broken floorings to endless cobwebbed windows, unbarring wooden casements and letting in the watery light that only made the inner desolation more ghostly conspicuous, but nothing human could I find, nor any prospect but that same one I had seen before of damp woodlands and marshy water-meadows out beyond.

Perhaps for half an hour had I adventured thus hopelessly, lost in the dusty bowels of that stupendous building; and then—just as I was near despairing of an exit and meditating a leap from a casement on to the stony terraces below—opening one final door, that might well have been but a household cupboard for the storing of linen and raiment, there, at my feet, was the great main staircase leading, by many a turn and staging, to the central hall below! I put, with the point of my sword, a cross upon the outside of that cupboard-door, so that I might know it again if need be, and then descended.

Had you seen me coming down those Tudor steps in that Tudor finery—my hand upon the hilt of my long steel rapier perked behind me, my great ruffle and my curled mustache, my strong soldier limbs squeezed into those sweet-fitting satin hose and sleeves, so stern and grim, so lonely and silent in the white glimmer of the morning shine that came from distant lattice and painted oriel—you well might have thought me scarcely flesh and blood—some old Tudor ancestor of that old Tudor hall stepped from a painter’s canvas just as he was in life, and come with beatless feet to see what cheer his gross descendants made of it where he had once lived so noisy and so jolly.

Down the steps I came, and into the banquet-hall, empty and deserted like all else, and so sauntered to the table head where I had supped the evening before. Not one trace of humankind had I seen since the night, and yet—that little thing quite startled me—the supper had been cleared away, another napkin spread, another plate, put out with fruit and bread, and a large beaker of good new milk stood by to flank them. I stared hard at that simple-seeming meal, and could not comprehend it. I was near sure the old man had not set it—yet, if he had, why was there but one plate, one place, one chair, one beaker? Was it meant for me or him? What fingers had pulled that fruit, or drawn that milk still warm from its source? I would wait, I thought, and strolled off to the windows, and down them all slowly in turn, then back again, to idly hum a favorite tune we had sung yesterday at Crecy. But still nothing came or stirred. Then I went into the hall and examined that trophy of weapons and tried them all, and then unbarred the great door and went out upon the terrace, there to dangle my satin legs over the balustrades during a long interval of gloomy speculation; but not a leaf was moving, not a sign or whisper could I see of that strange old fellow who had brought me hitherto, and now did his duty by his guest so quaintly.

At last I went back to the dining-place, and regarded that mysterious meal with fixed attention. “Now this,” I thought, “is surely spread for me, and if it is not then it should be. The master of a house may get him food how and when he likes; but the guest’s share is put ready to his hand. I have waited a long hour and more, the sun is high, surely that learned pedant could not mean to belay his courtesy by starving a stranger visitor! No, it were certainly affectation to wait longer: at the worst there must be more where these good things came from.” And being hungry, and having thus appeased my conscience, I clapped my sword upon the table and fell to work, and in a short space had made a light though sufficient meal and cleared everything eatable completely from the table.

I was the better for it, yet this strange solitude began to weigh upon me. But a few hours since—surely it was no more—I had been in a busy camp, bright with all the panoply of war, active, bustling; and here—why, the white mists seemed creeping through me, it was so damp and melancholy, the tawny mildew of these walls seemed settling down upon my spirit. Jove! I felt, by comparison of what I had been and was, already touched with the clammy rottenness of this place, and slowly turning into a piece of crumbling lumber, such as lay about on every hand—a tarnished, faded monument to a life that was bygone. Oh! I could not stand the house, and, taking my cap and sword, strolled down the garden, full of pensive thoughts, morose, uncaring, and so out into the woods beyond, and over hill and dale, a long walk that set the stagnant blood flowing in my sleepy veins, and did me tonic good.

Leaving the hall where so strange a night had been spent, I strode out strongly over hill and dale for mile after mile, without a thought of where the path might lead. I stalked on all day, and came back in the evening; yet the only thing worthy of note upon that round was a familiarness of scene, a certain feeling of old acquaintance with plain and valley, which possessed me when I had gone to the farthest limit of the walk. At one hilltop I stopped and looked over a wide, gently swelling plain of verdure, with a grassy knoll or two in sight, and woods and new wheat-fields shining emerald in the April sunlight, while far away the long clouds were lying steady over the dim shine of a distant sea. I thought to myself, “Surely I have seen all this before. Yonder knoll, standing tall among the lesser ones—why does it appeal so to me? And that distant flash of water there among the misty woodlands a few miles to westward of it? Jove! I could, somehow, have sworn there had been a river there even before I saw the shine. Some sense within me knows each swell and hollow of this fair country here, and yet I know it not. They were not my Saxon glades that spread out beneath me, and the distant stream swept round no such steep as that castled mount wherefrom I had set out for Crecy.” I could not justify that spark of vague remembrance, and long I sat and wondered how or when in a wide life I had seen that valley, but fruitlessly. Yet fancy did not err, though it was not for many days I knew it.

Then, after a time, I turned homeward. Homeward, was it? Well, it was as much thitherward as any way I knew, though, indeed, I marveled as I went why my feet should turn so naturally back to that gloomy mansion peopled only by shadows and the smell of sad suggestions. Perhaps my mind just then was too inert to seek new roads, and accepted the easiest, after the manner of weak things, as the inevitable. Be this as it may, I went back that wet, misty afternoon, alone with my melancholy listlessness through the damp dripping woods and coppices, where the dead ferns looked red as blood in the evening glow. I was so heedless I lost my way once or twice, and, when at length the dead front of the old house glimmered out of the mist ahead, the early night was setting in, and that lank, dejected garden, those ruined terraces, and hundred staring, empty windows frowning down on the grave-green courtyard stones seemed more forsaken, more mournful-looking even than it had the night before.

I found the front door ajar, exactly as it was left, and, groping about, presently discovered the tinder and steel. I made a light, and laughed a little bitterly to think how much indeed I was at home; then, in bravado and mockery, unsheathed my sword and went from room to room, in the gathering dusk, stalking sullen and watchful, with the gleam of light held above my head, down each clammy corridor and vault-like chamber; rapped with my hilt on casement and panels, and, listening to the gloomy echo that rumbled down that ghoulish palace, I pricked with my rapier-point each swelling, rotting curtain; I punctured every ghostly, swinging arras, and stabbed the black shadows in a score of dim recesses. But nothing I found until, in one of these, my sword-point struck something soft and yielding, and sank in. Jove! it startled me. ’Twas wondrous like a true, good stab through flesh and bone; and my fingers tightened upon the pommel, and I sent the blade home through that yielding, unseen “something,” and a span deep into the rotten wall beyond; then looked to see what I had got. Faugh! ’twas but a woman’s dress left on a rusty nail, a splendid raiment once—such as a noble girl might wear, and a princess give—padded and quilted wondrously, with yards of stitching down the front, wherefrom rude hands had torn gold filigree and pearl embroideries, and where the wearer’s heart had beat those rough fingers had left a faded rose still tied there by a love-knot on a strand of amber silk—a lovely gown once on a time, no doubt, but now my sword had run it through and through from back to bosom. Lord! how it smelled of dead rose, and must, and moth! I shook it angrily from my weapon, and left it there upon the rotten boards, and went on with my quest.

But neither high nor low, nor far nor near, was there to be found the smallest trace of my host or any living mortal. At last, weary and wet, and oppressed with those vast echoing solitudes, I went back to the great hall—passed all the untouched litter I had made in the morning—and so to the banquet-place. I walked up the long black tables set solemn with double rows of empty chairs, and lit the lamp that stood at top. It burned up brightly in a minute—and there beneath I saw the morning meal had been removed, the supper napkin neatly laid, and bread, wine, and cheese laid out afresh for one!

So unexpected was that neat array, so quaint, so out of keeping with the desolate mansion, that I laughed aloud, then paused, for down in the great vaulty interior of that house the echo took my laughter up, and the lone merriment sounded wicked and infernal in those soulless corridors. Well! there was supper, while I was tired and hungry I would not be balked of it though all hell were laughing outside. In the vast empty grate I made a merry fire with some old broken chairs, a jolly, roaring blaze that curled about the mighty iron dogs as though glad to warm the chilly hearth again, and went flaming and twisting up the spacious chimney in right gallant kind. Then I lifted the stopper of the wine-jar, and, finding it full of a good Rhenish vintage, set to work to mull it. I fetched a steel gorget from the trophy in the hall, poured the liquor therein, and put it by the blaze to warm. And to make the drink the more complete I spit an apple on my rapier point and toasted the pippin by the embers, thus making a wassail bowl of most superior sort.

I ate, and drank, and supped very pleasantly that evening, while the strong wind whistled among the chimney-stacks and rattled with unearthly persistence upon the casements, or opened and shut, now soft, now fiercely, a score of creaking distant doors. The spluttering rain came down upon the fire by which I sat in my quaint finery, warming my Tudor legs by that Tudor blaze; the tall, spectral things of the garden beyond the curtainless windows nodded and bent before the storm; loose strands of ivy beat gently upon the panes like the wet long fingers of ghostly vagrants imploring admission; the water fell with measured beat upon the empty courtyard stones from broken gargoyle and spout, like the fall of gently pattering feet, and the strangest sobbing noises came from the hollow wainscoting of that strange old dwelling-place. But do you think I feared?—I, who had lived so long and known so much—I, who four times had seen the substantial world dissolve into nothing, and had awoke to find a new earth, born from the dusty ashes of the past—I, who had stocked four times the void air with all I loved—I, for whom the shadowy fields of the unknown were so thickly habited—I, to whom the teeming material world again was so unpeopled, so visionary, and desolate? I mocked the wild gossip of the storm, and grimly wove the infernal whispers of that place into the thread of my fancies.

Hour by hour I sat and thought—thought of all the rosy pictures of the past, of all the bright beams of love I had seen shine for me in maiden eyes, all the wild glitter and delight of twenty fiery combats, all the joy and success, all the sorrow and pleasure, of my wondrous life; and thus thought and thought until I wore out even the storm, that went sighing away over the distant woodlands, and the fire, that died down to a handful of white ashes, and the wine-pot, that ran dry and empty with the last flames in the grate; and then I took my sword and the taper, and, leaving the care of to-morrow to the coming sunrise, went up the solemn staircase and threw myself upon the first dim couch in the first black chamber that I met with.

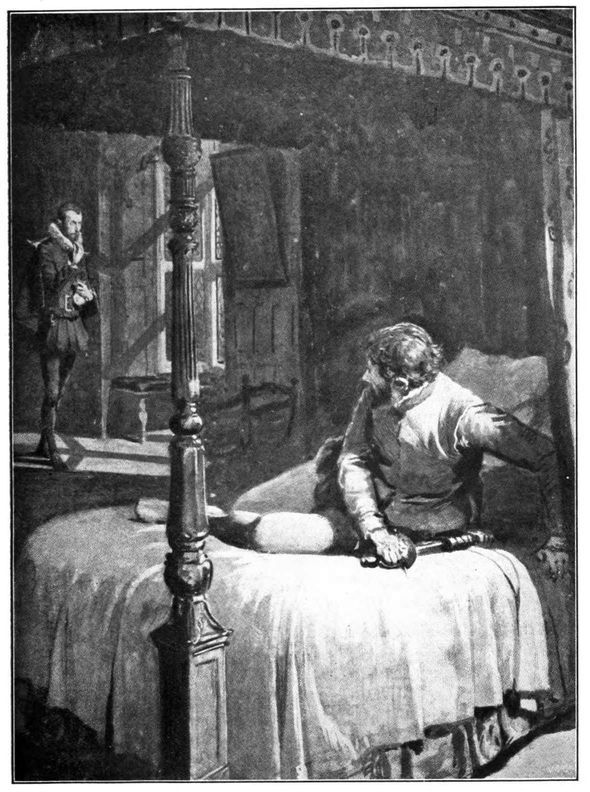

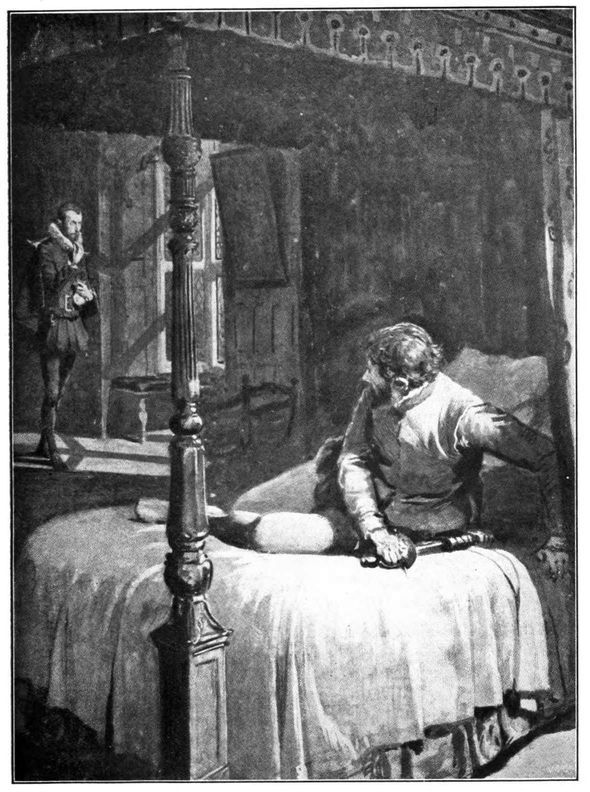

I threw myself upon a bed dressed as I was, but could not sleep as soon as I wished. Instead, a heavy drowsiness possessed me, and now I would dream for a minute or two, and then start up and listen as some distant door was opened, or to the quaint gusts that roamed about those corridors and seemed now and then to hold whispered conclave outside my door. It was like a child, I knew, to be so restless; but yet he who lives near to the unknown grows by nature watchful. It did not seem possible I had fathomed all the mystery there was in that gloomy mansion, and so I dozed, and waked, and wondered, waiting in spite of myself for something more all in the deep shadow of my rotten bed-hangings; now speculating upon my host, and why he tenanted such a life-forsaken cavern, and ate and drank from ancient crockery, and had store of moldy finery and rusty weapons; and then idly guessing who had last slept on this creaking, somber bed, and why the pillows smelled so much of moldiness, and mildew; or again listening to the wail of the expiring wind among the chimneys overhead, and the dismal sodden drip of water falling somewhere. Perhaps I had amused myself like that an hour, and it was as near as might be midnight: the low, white moon was just a-glimpse over the sighing treetops in the wilderness outside. I had been dozing lightly, when, on a sudden, my soldier ear distinctly caught a footfall in the passage without, and, starting up upon my elbow in the black shadow of the bed, I gripped the hilt of the sword that lay along under the pillows and held my breath, as slowly the door was opened wide, and, before my astounded eyes, a tall, dark figure entered!

It was all done so quietly that, beyond the first footfall and the soft click of the lifting latch, I do not think a sound broke the heavy stillness that, between two pauses of the wind, reigned throughout the empty house. Very gently that dusky shadow by my portal shut the door behind, and it might have been only the outer air that entered with him, or something in that presence itself, but a cold, damp breath of air pervaded all the room as the latch fell back.

I did not fear, and yet my heart set off a-thumping against my ribs, and my fingers tightened upon the fretted hilt of my Toledo blade as that thing came slowly forward from the door, and, big and tall, and so far indistinct, stalked slowly to the bed-foot, touching the posts like one who, in an uncertain light, reassures him by the feel of well-known landmarks, and so went round toward the latticed window. I did not stir, but held my breath and stared hard at that black form, that, all unconscious of my presence, slowly sauntered to the light and took form and shape. In a minute it was by the lattice and, to my stern, wondering awe, there, in the pale white moonshine, looking down into the desolate garden beyond with melancholy steadfastness, was the figure of a tall, black Spanish gallant. In that white radiance, against the ebony setting of the room, he was limned with extraordinary clearness. Indeed, he was a great silver column now of stenciled brightness against the black void beyond, and I could see every point and detail in his dress and features as though it were broad daylight. He was—or must I say, he had been?—a tall, slim man, long-jointed and sparse after the manner of his nation, and to-night he wore something like the fashion of his time—black hose and shoes, a black-seeming waistcoat, a loose outdoor hood above it, a slouch cap, a white ruffle, and a broad black-leather belt with a dagger dangling from it. So much was ordinary about him, but—Jove!—his face in that uncertain twilight was frightful! It was cadaverous beyond expression, and tawny and mean, and all the shadows on it were black and strong; and out of that dreary parchment mask, making its lifelessness the more deadly by their glitter, shone two restless, sunken eyes. He kept those yellow orbs turned upon the garden, and then presently put up a hand and began stroking his small pointed beard, still seeming lost in thought, and next, stretching out a finger—and, Hoth! what a wicked-looking talon it did seem!—the shape began drawing signs upon the mistiness of the diamond panes. At the same time he began to mutter, and there was something quaintly gruesome about those disconnected syllables in the midnight stillness; yet, though I leaned forward and peered and listened, nothing could I learn of what he wrote or said. He fascinated me. I forgot to speak or act, and could only regard with dumb wonder that outlined figure in the moonlight and the long-dead face so dreadfully ashine with life. So bewitched was I that had that vision turned and spoken I should have made the best shift to answer that were possible; there was some tie, I felt, between him and me more than showed upon the surface of this chance meeting of ours—something which even as I write I feel is not yet quite explained, though I and that shadow now know each other well. But, instead of speaking, that presence, man or spirit, from the outer spaces, left off his scratching on the window, and, with a shrug of his Spanish shoulders and a malediction in guttural Bisque, turned from the window-cell and walked across the room. As he did so I noticed—what had been invisible before—in his left hand a canvas bag, and, by the shape and weight of it, that bag seemed full of money. I watched him as he stalked across the room, watched him disappear into the shadow, and then listened, with every sense alert, to the click of the latch and the creak of the door as he left my chamber by the opposite side to that whereat he entered.

He kept those yellow orbs turned upon the garden

As those faint, ghostly footsteps died away slowly down the corridor, my native sense came back, and, in a trice, I was on foot, dressed as I had lain me down, and, snatching my sword and cloak in a fever of expectation, I ran over to the window and looked upon the writing. It was figures—figures and sums in ancient Moorish Arabesque; and the long, sharp nail-marks of that hideous midnight mathematician were still penciled clearly on the moonlit dew.

My blood was now coursing finely in my veins, and, hot and eager to see some more of this grim stranger, I strode across the room and stepped out into the passage. At first it seemed that he had gone completely, for all was so still and silent; but the white light outside was throwing squares of silver brightness from many narrow windows on the dusty floor—and there he was, in a moment, crossing the farthest patch, tall and silvery in that radiance, with his long, slim, black legs, his great ruffle, and flapping cloak—looking most wicked. I went forward, making as little noise as might be, and seeing my ghostly friend every now and then, until when we had traversed perhaps half that deserted mansion I lost him where three ways divided, and went plunging and tripping forward, striving to be as silent as I could—though why I know not—and making instead at every false step a noise that should have startled even ghostly ears. But I was now well off the trail, and nothing showed or answered. It was black as hell in the shadows, and white as day where the moonbeams slanted in from the oriels, and through this chilly checker I went, feeling on by damp old walls and worm-eaten wainscoting; slipping down crumbling stairs that were as rotten as the banisters which went to dust beneath my touch; opening sullen oaken doors and peering down the dreary wastes within; listening, prying, wondering—but nowhere could I find that shadowy form again.

I followed the chase for many minutes far into a lonely desert wing of the old house, then paused irresolute. What was I to do? I had my cloak upon one hand, and my naked rapier was in the other; but no light, or any means of making one. The vision had gone, and I found, now that the chase had ended, and my blood began to tread a sober measure, it was dank, chilly, and dismal in these black, draughty corridors. Worse still, I had lost all count and reckoning of where my bed had been, and, though that were small matter in such a house, yet somehow I felt it were well to reach the vantage-ground of more familiar places wherein to wait the morning. So, as nearly as was possible, I groped back upon my footsteps by tedious ways and empty chambers, low in heart and angry; now stopping to listen to the fitful moaning of the wind or the pattering rain-spots on the grass, or some distant panels creaking in distant chambers; half thinking that, after all, I had been a fool, and cozened by some sleepy fancy. And so I went back, dejected and dispirited, until presently I came to a gloomy arch in a long corridor, tapestried across with heavy hangings. Unthinkingly I lifted them, and there—there, as the curtains parted—thirty paces off, a bright moonlit doorway gently opened, and into the light stepped that same black-browed foreigner again!

I did what any other would have done, though it was not valiant—stepped back against the niche and drew the tapestry folds about me, and so hidden waited. Down he sauntered leisurely straight for my hiding-place, and as he came there was full time to note every wrinkle and furrow on that sullen, ashy face! Hoth! he might have been a decent gentleman by daylight, but in the nightshine he looked more like a week-dead corpse than aught else, and, with eyes glued to those twinkling eyes of his, and bated breath and irresolute fingers hard-set upon my pommel-hilt, I waited. He came on without a pause or sign to show he knew that he was watched, and, as he crossed the last patch of light, I saw the bag of gold was gone, and the hand that had carried it was wrapped in a bloody handkerchief. Another minute and we were not a yard apart. What good was valor there, I thought? What good were weapons or courage against the malignity of such an infernal shadow? I held back while he passed, and in a minute it was too late to stop him. Yet, I could follow! And, half ashamed of that moment’s weakness, and with my courage budding up again, I started from my hiding-place, and, brandishing my rapier, my cloak curled on my other arm as though I went to meet some famous fencer, I ran after the Spaniard. And now he heard me, and, with one swift look over his shoulder and a startled guttural cry, set off down the passage. From light to light he flashed, and shadow to shadow, I hot after him, my courage rampant now again, and all the bitterness and disappointment of the last few days nerving my heart, until I felt I could exchange a thrust or two with the black arch-fiend himself. ’Twas a brief chase! At the bottom of the corridor stood a solid oak partition—I had him safe enough. I saw him come to that black barrier, and hesitate: whereon I shouted fiercely, and leaped forward, and in another minute I was there where he had been—and the corridor was empty, and the paneled partition was doorless and unmoved, and not a sound broke the stillness of that old house save my own angry cry, that the hollow echoes were bandying about from ghostly room to room, and corridor to empty corridor!