CHAPTER XX

A bright dazzle of sunshine roused me with the following sunrise. I rubbed my sleepy lids and sat up, vaguely gazing round upon the tarnished hangings, the immovable white faces of the pictures on the wall, and the dusty floor whereon, in the grayness of countless years, was marked just the outlines of last night’s feet, and nothing more. However, it was truly a lovely morning, and, moved by that subtle tonic which comes with sunshine, I felt brighter and more confident.

Having dressed, I went down the old staircase again to the breakfast which would certainly be ready, unbarring as I passed the casements and setting wide the great hall door, that the cool breath of that spring morning might sweep away the mustiness of the old house, even humming a snatch of an old camp song, learned in Picardy, to myself the while. Thus, I gained the dining-hall in good spirits, and saw, as had been expected, a new meal set with modest food and drink for me, and me alone, but no other sign or trace of human presence.

I sat and ate, vowing as I did so this riddle had gone far enough unanswered, and before that shiny, sparkling world outside (all tears and laughter like a young maid’s face) was a few hours older I would know who was my host, who served me thus persistent and invisible, and what might be the service I was looked to to pay for such quaint entertainment. Therefore, as soon as the meal was done, I belted on my sword and straightened down my finery, the which had lost its creases and sat extremely well, and, smoothing the thick mass of my black Eastern hair under my velvet Tudor cap, sallied forth.

There was nothing new about the garden save the sunshine, and, having intently regarded the broad-terraced and mullioned front of the house without learning one single atom more than I knew before, I resolved to force a way round to the rear if it were possible. But this was not so easy. On one hand were thickets of shrub and bramble laced into dense, impenetrable barriers, and on the other great yew hedges in solemn ranks, with vast masses of ivy and holly forbidding a passage. But, nothing daunted, I walked down to these yews, and peering about soon perceived a tangled pathway leading into their fastness. It was a narrow little way, begrudgingly left between those sullen hedges, thick-grown with dank weeds below, and arched over by neglected growth so that the sun could not shine into these dusky alleys, and the paths were wet and chilly still.

Well, I pushed on, now to right and now to left, amid the tangles of one of those old mazes that gardeners love to grow, and until only the tall smokeless chimney-stacks of the deserted house shone red under the sunshine over the bough-tops in the distance, and then I paused. It was all so strangely quiet, and so lonesome—I had been solitary so long, it seemed doubtful whether any one was alive in the world but me—why, surely, I was thinking, there were no human beings at least about this shadow-haunted spot. It were idle to seek for them. I would give it up. And just as I was meditating that—had half turned to go, and yet was standing irresolute—Jove! right from the air in front of me, right out from the black bosom of the shadowy yew and ivies, there burst a wild elfin strain of laughter, a merry bubbling peal, a ringing cascade of fairy merriment, a sparkling avalanche of disembodied mirth, that, like some sweet essence, permeated on an instant all that gloomy place, and thrilled down the damp alleys, and shook the thousand colored drops of dew from bent and leaf, and vibrated in the misty prismatic sunshine up above, and then was gone, leaving me rooted to the ground with the suddenness of it, and half delighted and half amazed. But only for a moment, and then I leaped forward and saw a turning, and found at bottom of it a gap, and plunged headlong through!

It was a pretty scene I staggered into. In front of me spread the open center of the maze, a grassy space some twenty paces all about, and lying clear to the sunshine falling warm and strong upon it. In the midst of that fair opening, shut off from wind and outer barrenness, had once been a fountain with a basin, and, though the jet played no longer, yet the white marble pool below it, stained golden and green with moss and weather, held from brim to brim a little lake of sparkling water. And about that fountain, bright in decay, the green ferns were unwinding, while great clumps of gold narcissus hung trembling over their own reflection in the broken basin. Overhead, there was a blossoming almond-tree, a cloud of pale-pink buds wherefrom a constant cheerful hum of bees came forth, and a pale rain of petals fell on to the ground beneath and tinted it like a rosy snow. No other way existed in or out of that delightful circle save where I had entered, but little paths ran here and there among the grass, and industrious love had marked them out with pretty country flowers—pale primroses all damp and cool among the shadows, broad bands of purple violets lining seductive alleys, splendid starlike saffron outshining even the gorgeous sun, and blushing daisies, with varnished kingcups where the fountain ran to waste. It was as pretty a dominion—as sweet an oasis in that dank, dark desert beyond—as you could wish to see, and the clear, strong breath of flowers, and the warm wine of the sunshine set my blood throbbing deep and swift to a new sense of love and pleasure as I stood there spellbound on the dewy threshold.

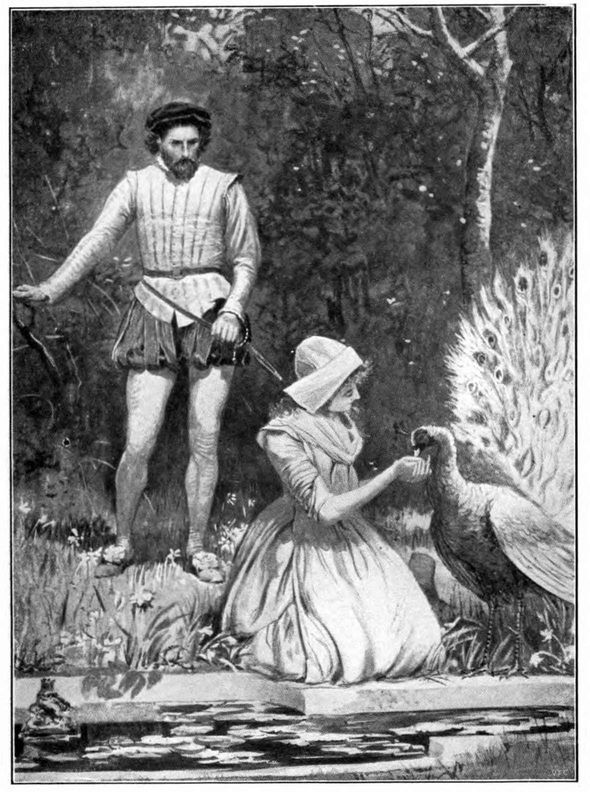

But, fair as earth and sky looked in that magic circle, they were not all. Kneeling at the broken marble fountain, her dainty sleeves rolled to pearly elbows, the strands of her loose brown hair dipping as she bent over the shining water, with white muslin smock neatly bunched behind her, a milky kerchief knotted across her bosom, and a great country hat of straw by her side, knelt a fair young English girl. She did not see me at once, her face was turned away, and on her other hand she was tending a noble peacock, a splendid fowl indeed—as stately as though he were the Suzerain of all Heaven’s chickens—ivory white from bill to spurs, crested with a coronet of living topaz, and with a mighty fan upreared behind him of complete whiteness from quill to fringe, saving the last outer row of gorgeous eyes that shone in gold and purple and amethyst refulgent in that spotless field!—a magnificent bird indeed, and fully wotting of it—and that kneeling maid was dipping water for him in her rosy palm, and the great bird was perched upon the marble rim and dropping his ivory beak into that sweet chalice and lifting his lovely throttle and flashing coronet to the sky ever and anon, while the thrill of the girl’s light laughter echoed about the place, and the almond-blossoms showered down on them, and the bees hummed, and the sweet incense of the spring was drawn from the warm, budding earth, flowers glittered, the sun shone, and the sky was blue, as I, the intruder, stood, silent and surprised, before that dainty picture.

The great bird was dropping his ivory beak into the sweet chalice

In a moment the girl looked up and saw me in my amber suit and ruffle, my rapier and cap, standing there against the black framing of the maze; and then she did as I had done—stared, and rubbed her eyes, and stared again! In a moment she seemed to understand I was something more than a fancy, whereat, with a little scream of fear, she sprang to her feet, and, crossing the kerchief closer on her bosom, pulled down her sleeves and backed off toward the almond-tree. But I had that comely apparition fairly at bay, and, after so many hours without company, did not feel a mind to let her go too easily, whether she proved fay or fairy, nymph, naïad, or just plain country flesh and blood.

I pulled off my cap, and, with a sweeping bow, advanced slowly toward her, whereon she screamed again.

“Fair girl,” I said, “I grieve to interrupt so sweet a picture with my uninvited presence, but, wandering down these paths, your laughter burst upon the stillness and drew me here.”

“And now, Sir,” quoth that fair material sprite, recovering herself, and with a pretty air, “you would ask the shortest way to the public road. It lies there to your left, beyond the hollybank you see over by the meadows.”

“Why, not exactly that,” I laughed. “I have an idle hour or two on hand, and, since you seem to have the same, I would rather rest content with the good fortune which brought me hither than try new paths for lesser pleasures. If you would sit, I think this grassy mound is broad enough for two.”

I meant it well, but the maid was timid, and far from rescue in the wilderness of that maze. The color mounted to her cheeks until they were pinker than the almond-buds overhead. She looked this way and that, and gave one fleeting glance round the strong, close-set walls of that sunny garden among the yews, then just one other glance at me, that dangerous stranger in silk and satin, standing so gallant, cap in hand, and finally she was away, running like a hind toward the only outlet, the gap by which I had come in. But was I to be robbed of a pretty comrade so? Was the lovely elf of the neglected garden to slip between my fingers without answering one single question of the many I would ask? I spun round upon my heels, and, quick as that maiden’s feet were on the turf, mine were quicker. We got to the gap together, and, in another minute, her kirtle fluttering in the breeze, her loose hair adrift, and the flush of fear and exertion on her youthful face, that comely lady was struggling in my grasp.

I held her just so long as she might recognize how strong her bonds were, then set her free. If she had been pink before, that maid was now ruddier than the windflowers in the grass. “Oh, fie, Sir!” she began, as soon as she could get her breath. “Oh, fie, and for shame! You wear the raiment of a gentleman, you carry courtly arms, you do not look at least a rough, uncivil rogue, and yet you burst into a privy garden and fright and offend a harmless girl—oh! for shame, Sir!—if gentleness and courtesy are so poor barriers, we shall need to look the better to our hedges—let me by, Sir!” and, gathering her skirts in her hand and tossing back her head with all the haughtiness she could command, that damsel looked me boldly in the eyes.

Fair, foolish girl! she thought to stare me down—I, who had eyed unmoved a thousand sights of dread and wonder—I, who had mocked the stare of cruel tyrants and faced unblanching the worst that heaven or hell could work—what! was I to be out of countenance under the feeble battery of such gentle orbs as those? ’Twas boldly conceived, but it would not do, and in a moment she felt it, and her eyes fell from mine, the color rushed again from brow to chin, she let her flowered skirt fall from her grip, she turned away for a moment, and there and then burst out a-crying behind her hands as though the world were quite inside out.

Now, to stand the fair open assault of her eyes was one thing, but such sap as this was more than my resolution could abide. “You do mistake me, maid, indeed,” I cried. “I swear there is no deed of courtesy or good-will in all the world I would not do for you.”

“Why, then, Sir, do the least and easiest of all—stand from that gap and let me pass.”

“If you insist upon it, even that I must submit to. There!—there is your way free and unhampered!” and I stood back and left the passage clear—“and yet, before you go, fair lady, let me crave of your courtesy one question or two, such as civility might ask, and courtesy very reasonably answer.”

Now that maid had dried her tears, and had been stealing some sundry glances at me under the fringe of her wet lashes while we spoke, and as a result she did not seem quite so wishful to be gone as she had been. She eyed the free gap in the tall wall of yew and holly, and then, demurely, me. The pretty corners of her mouth began to unbend, and while her fingers played among her ribbons, and the color came and went under her clear country skin, feminine curiosity got the better of timidity, and she hesitated.

“Oh!” she murmured, “if it were a civil question civilly asked, I could wait for that. What can I tell you?”

“First then, are you of true material substance, not vagrant and spiritual, but, as you certainly look, a healthy, plain planed mortal?”

“Had I been else, Sir,” the damsel answered, with a smile, “I had found a short way out of the trap you saw fit to hold me in.”

“That is true, no doubt, and I accept this initial answer with due thanks. I had not asked it, but lodging so long amid shadows sets my prejudice against the truth, even of the sweetest substance.”

“And next, Sir?”

“Next, how came you in this lonely place, with these pretty playthings about you? How came you in my garden here, where I thought nothing but silence and sadness grew?”

“Your garden! What hole in our outer fences gave you that warrant, Sir?” queried the young lady, with a toss of her head. “How long user of trespass makes that right presumptive? Faith! until you spoke I thought the garden was mine and my father’s!” and the young lady, for such I now acknowledged her to be, looked extremely haughty.

“What! Hast thou, then, a father?”

“Yes, Sir. Is it so unusual with our kind that you should be surprised?”

“And who is thy father?”

“A very learned man indeed, Sir; one who hath more wit in his little finger than another brave gentleman will have in all his body. Of nature so courteous that he instinctively would respect the privacy of a neighbor’s property and manners, so finished he would never stay a maiden at her morning walk to bandy idle questions with her all out of vanity of black curled hair and a new, mayhap unpaid-for, yellow suit. If you had no more to ask me, Sir, I think, I would wish you good-day.”

“But stay a minute. It seems to me I might know thy father; and this is the very point and center of my inquisitiveness.”

“If you did, it were much to your advantage, but I doubt it. He is recluse and grave, not given to chance companions, or, in fact, to friend with any but some one or two.”

“Ah! that may well be so,” I said thoughtlessly, speaking with small consideration and recalling the vision of my ancient host just as it came to me—“a sour, wizened old carl, clad in rusty green, a-straddle of a spavined, ragged palfrey; mean-seeming, morose, and sullen—why, maid, is that thy father?”

“No, Sir!”

“Gads!” I laughed, “it was discourteously spoken. I should have said, now I come to reflect more closely on it, a reverent gentleman, indeed, white-bearded and sage, with keen eyes shining severe, the portals of a well-filled mind. A carriage that bespoke good breeding and gentle blood; raiment that disdained the pomp of silly, fickle fashion, and a general air of learning and of mildness.”

“My father, Sir, to the very letter, Master Adam Faulkener, the wisest man, they say, this side of the Trent, and greatly (I know he would have me add) at your service.”

“And you?”

“I am Mistress Elizabeth Faulkener, daughter to that same; and if, indeed, you know my father, then, as my father’s friend, I tender you my humble and respectful duty,” and the young lady half mockingly, and half out of gay spirit, picked up her flowered muslin skirt, by two dainty fingers, on either side and made me a long, sweeping curtesy.

A pretty flower indeed, for such a rugged stem!

“But this is only half the matter, fair girl,” I went on, when my responding bow had been duly made. “If that venerable gentleman indeed be thy father, and this his house and thine, it is more strange than ever. I came here two evenings since by his explicit invitation, but since that time I have not set eyes upon him. High and low have I hunted, I have pricked arras and rapped on hollow panels, trodden yon ghostly corridors at every hour of the day and night, yet for all that time no sight or sound of host or hostess could I get. Now, out of thy generous nature and the civility due to a wondering guest, tell me how was this.”

“Why, Sir! Do you mean to say since two nights past you have been lodged back there?”

“Ah! three days, in yon grim, moldy mansion.”

“What! there, in that melancholy front of the many windows—and all alone?”

“The very simple, native truth!—alone in yonder tenement of faint, sad odors and mournful, sighing draughts, alone save for a mind stocked with somewhat melancholy fancies—mislaid by him, it seemed, who brought me thither—dull, solitary, and damp—why, damsel!”

And, in faith, when I had got so far as that, the maiden sank back upon a grassy heap and hid her face behind her hands, and gave way to a wild, tumultuous fit of laughter, a golden cascade of merriment that fell thick and sparkling from the sunny places of her youthful joyance, as you see the heavy rain-drops glint through a bright April sky; a wild, irresistible torrent of frolic glee that wandered round the faroff alleys, and raised a hundred answering echoes of pleasure in that enchanted garden.

Presently the maid recovered, and, putting down her hands, asked—“And your meals—how came you by them?”

“They were laid for me twice each day in the great hall by unseen hands, most punctual and mysterious. ’Twas simple fare, but sufficient to a soldier, and each time I cleared the table and went afield, when I came back it was reset; yet no one could I see—no sound there was to break the stillness——”

Again that lady burst into one of her merry trills, and, when it was over, signed me to sit beside her. I was not loth. She was fair and young and tender—as pretty an Amaryllis as ever a country Corydon did pipe to. So down I sat.

“Now,” said she, “imprimis, Sir, I do confess we owe you recompense for such scant courtesy; but I gather how it happened. This is, as I have said, my father’s house, and mine; and time was, once, it has been told me, when he had near as many servants as I have flowers here, with friends unending; and all those blank windows, yonder, were full of lights by night and faces in the day. Then this garden was trim—not only here but everywhere—and great carriages ground upon the gravel drive, and the courtyard was full of caparisoned palfreys. That was all just so long ago, Sir, that I remember nothing of it.”

“I can picture it, damsel,” I said, as she sighed and hesitated; “and how came this difference?”

“I do not know for certain—I have often wondered why, myself—but my father presently had spent all his money, and perhaps that somehow explained it,” sighed my fair philosopher. “Then, too, he took studious, and let his estate shift for itself, while he pored over great tomes and learned things, and hid himself away from light and pleasure. That might have scared off those gay acquaintances—might it not, Sir?” queried the lady so unlearned in worldly ways.

“It were a good recipe, indeed,” was my answer: “none better! To grow poor and wise is high offense with such a gilded throng as you have mentioned. So then the house emptied, and the gates no longer stood wide open; the garden was forsaken, and grass grew on thy steps; owls built in thy corridors—a dismal picture, and sad for thee, but this does not explain the strange entertainment I have had. Where is your father lodged? And you—how is it we have not met before?”

“Oh,” said the damsel, brightening up again, “that is easily explained. When his friends left him, my father dismissed all his servants but one—a Spanish steward—and good old Mistress Margery, my nurse (and, saving my father, my only friend), then lodged himself back yonder in the far rear of our great house, and there I have grown up.”

“Like a fair flower in a neglected spot,” I hazarded.

“Ah! and secure from the shallow tongues of silly flatterers, old Margery tells me. Now, my father, as you may have noted, is at times somewhat visionary and absent. It thus may well have happened that, bringing you here a guest, he would by old habit have taken you, as he was so long accustomed, to the great barren front and lodged you so. Once lodged there, it is perfectly within his capacity to have utterly forgot your very existence.”

“But the meals—for whom were they spread, if not for me?”

“Why, simply for my father. He has, where he works, a cupboard, wherein is kept brown bread and wine, and, sometimes, when studious studies keep him close, he goes to it and will not look at better or more ordered meals. Then, again, when the fancy takes him, he will have a place put for himself in the great deserted hall, and sups there all alone. Now, this has been his mood of late, and I can only fancy that when you came the whim did change all on a sudden, and thus you inherited each day that which was laid for him, who, too studious, came not, and old slow-witted Margery, finding every time the provender was gone, laid and relaid with patient remembrance of her orders.”

“A very pretty coil indeed!—and I, no doubt, being sadly wandering afield all day, just missed thy ancient servitor each time.”

“And had you ever come in upon her heels you would have seen her hobble up one silent corridor and down another, and press a button on a panel, and so pass through a doorway that you would never find alone, from your tenement to ours. Oh, it makes me laugh to think of you pent there! I would have given a round dozen of my whitest hen’s eggs to have been by to see how you did look.”

“That had been a contingency, fair maid, which had greatly lightened my captivity,” I answered; and the lady went babbling on in the prettiest, simplest way, half rustic and half courtly in her tones, as might be looked for in one brought up as she had been.

For an hour, perhaps, we lay and basked in the pleasant warmth, while the rheums of melancholy and dampness were slowly drawn from me by the sun and that fair companionship, then she rose, and, shaking a shower of almond petals from her apron, re-knotted her kerchief, and, taking a look at the sky, said it was past midday and time for dinner. If I liked, she would guide me to her father. Up I got, and, side by side with that fair Elizabethan girl, went sauntering through her flowery walks, down past shrubberies and along the warm red old wall of her great empty house, until we came into a quiet way overgrown with giant weeds and smelling sweet of green sheep’s parsley and cool, fair vegetable odors. Here the maid lifted a latch, and led me through a well-hidden gateway into the sunny rearward courtyard.

It showed as different as could be from the dreary front. The ground was cobblestones all neatly weeded round a square of close-cut grass. On one side the great black wall of the manor-place towered windowless above us, with red roofs, mighty piles of smokeless chimney-stacks and corbie steps far overhead; and, on the other hand, at an angle to that wall, were lesser buildings to left and right, enclosing the grass plot and shining in the sun, warm, lattice-windowed, quaint-gabled. The third side of the square was open, and sloped down to fair meadows, beyond which came flowering orchards, bounded by a brook. Moreover, there was life here, plain, homely, honest country life. The wild, loose-hanging roses and eglantine were swinging in the sunshine over the deep-seated porches of these modest places; the lavender smoke was drifting among the budding branches overhead, proud maternal hens were clucking to their broods about the open doorways; there were blooming flowers growing by one deep-set window—ah! and fair Mistress Elizabeth’s snowy linen was all out on cords across that pretty sunny courtyard, struggling in sparkling, white confusion against the loose caresses of the April wind.

“And look you there,” cried Mistress Faulkener, when she saw it, pointing far down the distant meadows, “’tis there we keep our milk and cows—oh! as you are courteous, as you would wish to deserve your gentle livery, count those cattle for a minute,” and thereat, while I, obedient, turned my back and mustered the distant beasts grazing knee-deep among the yellow buttercups—she outflew upon those linens, and pulled them down and rolled them up in swathes, and set them on a bench; then tucked back some disheveled strands of hair behind her ears, and, somewhat out of breath, turned to me again.

“Here,” she said, “on this side lives old Margery and our steward, black Emanuel Marcena; there, on the other, is my room—that one with the flowers below and open lattices. Next is my father’s; below, again, is the room where we do eat; and all that yonder—those many windows alike above, and those steps going down beneath the ground—those half-hidden cobwebbed windows ablink with the level of the turf—that is where my father works.”

“By all the saints, fair girl!” I exclaimed impetuously, as she led me toward that place, “thy father’s workshop is on fire! See the gray smoke curling from the lintel of the doorway, and the broken panes—and yonder I catch a glint of flame! Here, let me burst the door!” and I sprang forward.

But the lady put her hand upon my arm, saying with a somewhat rueful smile, “No, not so bad as that—there is fire there, but it is servant not master. Come in and you shall see.” She took me down six damp stone steps, then lifted the latch of a massy, weather-beaten, oaken doorway, and led me within.

It was a vast, dim, vaulted cellar. The rough black roof of rugged masonry was hung by vistas of such mighty tapestries of grimy cobwebs as never mortal saw before. On the near side the row of little windows, dusty and neglected, let in thin streams of light that only made the general darkness the more visible. All the other wall was rough and bare; beset with great spikes and nails wherefrom depended a thousand forms of ironware, and ancient useless metal things, the broken, rusty implements of peace and war. The floor seemed, as I took in every detail of this subterranean chamber, to be bare earth, stamped hard and glossy with constant treading, while here and there in hollows black water stood in pools, and gray ashes from a furnace-fire margined those miry places. It was a gloomy hall, without a doubt, and as my eyes wandered round the shadows they presently discovered the presiding genius.

In the hollow of the great final arch was a cobwebbed, smoke-grimed blacksmith’s forge and bellows. The little heap of fuel on it was glowing white, and the curling smoke ascended part up the rugged chimney and part into the chamber. On one side of this forge stood a heavy anvil, and by it, as we entered, a man was toiling on a molten bar of iron, plying his blows so slow and heavy it was melancholy to watch them. That man, it did not need another glance to tell me, was my host! If he had looked gaunt and wild by night, the yellow flicker of the furnace and the pale mockery of daylight which stole through his poor panes did not improve him now. The bright fire of enthusiasm still burned in his keen old eyes, I saw, but they were red and heavy with long sleeplessness; his ragged, open shirt displayed his lean and hairy chest, stained and smudged with the hue of toil; his arms were bare to the elbow, and his knotted old fingers clutched like the talons of a bird upon the handle of the hammer that he wielded. Grim old fellow! He was near double with weariness and labor; the breath came quick and hectic as he toiled; the painful sweat cut white furrows down his pallid, ash-stained face; and his wild, gray elfin locks were dank and heavy with the foul fumes of that black hole of his. Yet he stopped not to look to left or to right, but still kept at it, unmindful of aught else—hammer, hammer, hammer! and sigh, sigh, sigh!—with a fine inspired smile of misty, heroic pleasure about his mouth, and the light of prophecy and quenchless courage in his eyes!

It was very strange to watch him, and there was something about the unbroken rhythm of his blows, and the inflexible determination hanging about him, that held me spellbound, waiting I knew not for what, but half thinking to witness that red iron whereinto his soul was being welded spring into something wild and strange and fair—half thinking to witness these sooty walls fall back into the wide arcades of shadowy realm, and that old magician blossom out of his vile rags into some splendid flower of humankind. It was foolish, but it was an unlearned age, and I only a rough soldier. That fair maid by my side, more familiar with these strange sights and sounds, roused me from my expectant watching in a minute.

She had come in after me, had paused as I did, and now with pretty filial pity in her face, and outspread hands, she ran to that old man and laid a tender finger upon his yellow arm, and stayed its measured labor. At this he looked up for the first time since we entered, as dazed and sleepy as one newly waked, and, seeing that he scarce knew her, Elizabeth shook her head at him, and took his grizzled cheeks between her rosy palms, and kissed him first on one side and then on the other, kissed him sweet and tenderly upon his pallid unwashed cheeks, and then, with kind imperiousness, loosed his cramped fingers from the hammer-shaft and threw it away, and led him by gentle force back from his forge and anvil. “Oh, father!” she said, bustling round him and fastening up his shirt and pulling down his sleeves, and looking in his face with real solicitude, “indeed I do think you are the worst father that ever any maid did have,” and here was another kiss. “Oh! how long have you worked down here? Two nights and days on end. Fie, for shame! And how much have you eaten? What? Nothing, nothing all that time? Did ever child have such a parent? Oh! would to Heaven you had less wisdom and more wit—why, if you go on like this, you will be thinner than any of these spiders overhead in springtime—and weary—nay, do not tell me you are not—and, oh! so dirty, alack that I should let a stranger see thee like this!” and, taking her own white kerchief from her apron, that damsel wiped her father’s face in love and gentleness, and stroked his gritty beard and smoothed, as well as she was able, his ancient locks, then took him by the hand and pointed to me, standing a little way off in the gloom.

At first the old man gazed at the amber-suited gallant shining in the blackness of his workshop, stolidly, without a trace of recognition, but, when in a minute or two by an effort he drew his wits together, he took me for one of those gay fellows, who, no doubt, had haunted his courtyards and spent his money in brighter times, and taxed me with it. But I laughed at that and shook my head, whereon he mused—“What! are thou, then, young John Eldrid of Beaulieu, come to pay those twenty crowns your father borrowed twelve years since?”

No! I was not John Eldrid, and there were no crowns in my wallet. Then I must be Lord Fossedene’s reeve come to complain again of broken fences and cattle straying, or, perhaps, a bailiff for the Queen’s dues, and, if that were so, it was little I would get from him.

Thereon his daughter burst out laughing and stroking the old man’s hand. “Oh, father,” she said gently, “you were not always thus forgetful. This excellent gentleman I found trespassing among my flowers, and did arrest him; he is your guest, and declares you brought him here two nights since, lodging him in our empty front, where he has subsisted all this time on melancholy and stolen meals. Surely, father, you recall him now?”

The old man was puzzled, but slowly a ray of recollection pierced through the thick mists of forgetfulness. Indeed, he did remember, he muttered, something of the kind, but it was a sturdy, shrewd-looking yeoman, tall, and bronzed under his wide cap, a rustic fellow in country cloth that he had brought along, and not this yellow gentleman. So then I explained how he had resuited me, and jogged his memory gently, lifting it down the trail of our brief acquaintance as a good huntsman lifts a hound over a cold scent, until at last, when he had given him a cup of red wine from his cupboard in the niche, his eyes brightened up, the vacuity faded from his face, and, laughing in turn, he knew me; then, holding out two withered hands in very courteous wise, old Andrew Faulkener welcomed me, and in civil, courtly speech, that seemed strange enough in that grim hole, and from that grizzly, bent, unwashed old fellow, made apology for the neglect and seeming slight which he feared I must have suffered.

We spoke together for some minutes, and then I ventured to ask, “Was there not something, Master Faulkener, you had to tell or ask of me? I do remember you mentioned such a wish that evening when we parted, and certain circumstances of our short friendship make me curious to know what service it is I have to pay you in return for the hospitality your goodness put upon me.”

“In truth there was something,” Faulkener answered, with a show of embarrassment, “but it was a service better sought of frieze than silk.”

“Tell it, good Sir, tell it! It were detestable did silk repudiate the debts that honest frieze incurred.”

“Why, then, I will, and chance your displeasure. Sweet Bess, get thee out and see to dinner. This gentleman will dine with me to-day!” And as Mistress Elizabeth picked up her pretty skirts and vanished up the grass-grown steps the old recluse turned to me.