CHAPTER XVIII

A DESPERATE BETROTHAL

At the farthest limit of the cave we leaned upon the rock, and looked at that wicked, weaving head. Twice before had I seen it, but never in such circumstances as this. On both occasions we had been men alone. The peril had been distributed, so to speak, amongst us all. But with a girl, and a beautiful girl moreover, with whom I happened to be desperately in love—to have that outrageous atrocity mouthing upon her and me alone, and to feel that any accident might send her into its bestial maw—Good God! it might turn any brain. I stood between Gwen and the entrance and tried to smile into her face.

“I wouldn’t look that way, if I were you,” said I persuasively. “He’ll take himself off directly, I hope.”

Her lips were very white and they trembled unrestrainedly, but she smiled back into my eyes—a ghostly, uncertain sort of smile, though, I must confess.

“I don’t mind. Not much at least.” Then with a strained attempt to look at the humorous side of it she added, “What an opportunity for M. Lessaution and his squirt.”

I loved to see the pluck of her, and answered cheerfully.

“Garlicke will be distracting the brute’s attention directly with that Männlicher rifle,” said I. “I happen to know he took it up with him when we moved camp, for use in just such a possibility as this. He’ll be trying the effect of the bullet with the top bitten off,” I added to keep the light side of the question uppermost, though it was a watery sort of sprightliness at the best.

From the edge above, where the weight of the great body was pressing, a lump of granite fell, and splashed into splinters in the narrows of the gulf. It widened the mouth of the fissure by a foot or more. The horrible trunk surged forward a yard or two, and one of the huge legs, dropping from between the belly and the rock, slid into the opening. The five white claws waggled and gripped at empty space, and the gloom in the cave increased. Fidget was beyond barking now, and backed against the uttermost crevices with a sort of bleating gasp. I think that never have I seen unadulterated terror more plainly expressed on an animal’s features.

With the increased room for the body, the long sinuous neck came forward a like space. The thin snout was now fairly in the cavern. The nauseous breath hissed at us in gusts—sickening as a plague wind.

Suddenly the lithe neck stiffened. The evil eyes concentrated their gaze upon Gwen. Their stare seemed to go past my cheek with the searing directness of a flash-light. In an instant the memory of the power that lay in that wicked glare came back to me.

I dashed forward and clapped my palms upon Gwen’s face, calling to her wildly to close her eyes. I gathered her to my bosom—and oh, the ecstasy of it, even in that desperate stress—and stammered incoherently of the fatal trap that lay in that unwinking gaze. She was content enough to bury her face in the folds of my loose jacket, and thus for a moment we stood shuddering. Fidget crept and fawned shiveringly about Gwen’s skirts.

I kicked my foot against an object on the floor. It was the tin of mustard Gwen had been carrying when she started on that mad race down the boulders. It was new and shining, just out of store. I held it before my face to look at the reflection therein.

Finding his efforts unavailing, the Monster was drawing his head back into the outer part of the cave, relaxing his tense glare. We turned to face him. He curved his neck into a half-circle, his great throat muscles working with swallowings. Then with a sudden dart he flung it out upon us, gaping wide his mouth.

With a rasp and a roar his breath burst upon us, and upon the wall of rock at our back, hissing stridently like a gale through taut rigging. It beat us back almost irresistibly in the return draught, thrusting us out from the back of the cave toward his waiting lips. For one desperate moment we swayed in that noisome gust, and my free arm—for one still encircled Gwen’s waist—whirled in the air frantically as I braced myself to meet it. But as its first strength died down I flung myself with Gwen upon the ground, and grasping at a ledge hung on with despair’s own grip.

In the case of Fidget the Monster’s wile defeated his object. The back-swirl of his breath whisked the little dog like a leaf past the lowering head and on into the outer cleft. With a sound half bark, half squeal, she leaped upon the unwieldy body before the neck could coil itself out of the inner cave. We heard her yapping pass swiftly out among the boulders, and die away up the empty lake-side.

There was the thud of a bullet on the thick hide, and the crack of a rifle followed smartly on the shot. A flake or scale of parchmenty skin floated past the cave mouth, and rustled slowly into the depths below; not by so much as the flicker of an eyelid did the brute show that he had felt anything. Another shot followed, with the same result. They clattered on—above a score of them—but they worried him no more than the buzzings of mosquitoes. Finally one must have hit a wart-like excrescence on his shoulder. A lump about the size of my fist fell with a flop upon the stones, glanced ruddily for a second, and bounced on into the depths below. But it left a tell-tale smear upon the granite, and scarlet drops trickled down the hanging neck, dripping in a small pool at the threshold of the cave. Yet the Monster lay unheeding, and we began to gasp with the unutterable murkiness of his breathing, which filled the air.

At Gwen’s request I passed her the tin of mustard, and she held it like a smelling-bottle to her nostrils, to get relief from the disgusting fog. We began to pass it backward and forward to one another, and it was then that an inspiration—I think I may justly call it that—flashed into my brain.

With the tin in my hand I turned to face the great head again, waiting till the thin lips parted in one of their deep-drawn breaths. Then I tossed my missile accurately toward the open jaws, and like a flash of crimson the gums gaped wide and the yellow teeth closed upon it. For a single instant we saw it gleam brightly between them.

There was a scrunch and a grinding sound among the great fangs, and then the yellow powder sank bitingly into the saliva. The brute opened his mouth, and a bellow pealed out of the strained throat, enveloping us in a volume of merciless sound and hot, putrid air. The long pink tongue slavered and twisted between the burning gums, showing ruddy streaks where the metal had gashed it. In one such ragged wound a remnant of the bright tin was still sticking; the flaming paste of powder and saliva was filling the torn veins with agony.

He dashed his head desperately from side to side, slamming it on the hard rock sides of the cavern. His unearthly screams threatened to burst our ear-drums. He beat the air with his great clumsy foot, and we could hear the thunderous boom of his great tail against the timbers of the ship.

Finally with the swiftness of an escaping bird the tortured head fled out of the cave mouth, and we heard his great carcass drag and rustle from the cleft. The blessed sunlight began to flow down to us again, and the filthy stench began to fade.

I let go my grip upon the rock, and, more unwillingly, my encirclement of Gwen’s waist. I looked inquiringly into her eyes as I helped her up. She staggered as she rose, and for one delightful moment clung to me. I felt that mere courtesy bade me tender again my support, and so for two or three delicious seconds we stood. Then she found her voice and the ghost of a smile.

“I think you’re quite the cleverest person I ever met,” she said gratefully. “How on earth did you come to think of the mustard?”

“I really haven’t the least idea,” said I honestly. “His mouth was there and I had the tin in my hand. It seemed the most natural thing in the world to throw it in. The effect was more than I dared to hope for.”

She drew herself unostentatiously away from my arm as she spoke, and leaned against the rocks behind her.

“Well,” she remarked, “we’ve saved poor little Fidget, at any rate. Even if we’re doomed to be devoured we shall have the satisfaction of knowing that.”

“We!” said I rebukingly. “Should I ever have been such a sentimentalist as to risk a horrible death for a dog?”

“I rank above Fidget in your opinion then, as you have chosen to accompany me into this trap. You do me too much honor,” and she bowed to me charmingly.

I couldn’t quite command myself to answer this in any ordered phrase, but I suppose the expression on my face must have spoken. At any rate Gwen blushed delightfully, and continued rather hurriedly, “Don’t you think we might make a run for it now?”

“I’ll reconnoitre,” said I, “and see if he’s really taken himself off or not.”

I climbed gingerly out of the cleft, and very cautiously raised my head above the edge. No, by no manner of means was he gone. He was lying about fifty yards away, banging his head upon the ground and lashing the boulders with his tail; some of them were smitten to splinters as I watched. His mouth still dripped yellow saliva, and his teeth were meeting with resounding cracks. His tongue still lapped itself about his tortured lips, and in his agony he rolled over, writhing upon his back and beating his four great limbs convulsively toward the sky. Lumps of his scaly skin were scattered about on the granite as feathers scatter from a shot bird. His nails clattered as they swept an overhanging mass of granite in one of their aimless gyrations. Finally there was one last angry flurry of legs and tail, and he rolled back upon his belly; his horny eyelids closed; his head sank wearily upon his fore-arms.

As I turned to tell Gwen I kicked a stone beside me. It fell with a metallic clang, and in a moment the green eyes were open and staring at me. He lifted his head, and his huge limbs began to shove his carcass back toward me. There was a revengeful glare in those baleful eyes, and I popped back into the cleft like a rabbit into his burrow.

I heard him come dragging along above. Then, looking up, I saw the thin snout just overlap the edge and lie still. Evidently he was settling down to his sentinelship. Afraid of another dose of the biting pain we had inflicted, he did not dare to venture his head again into our cave. He meant to starve us out.

Gwen looked up hopefully as I returned, but I had to shake my head at her glance of inquiry.

“No good just at present, I’m afraid. He’s like the hosts of Midian, prowling and prowling around.”

“Well, I suppose it can’t be helped. But I do wish we’d had something a little more nutritious than mustard, useful as it’s been. I’m simply starving. It’s more than lunch-time by half-an-hour.”

“That can be arranged,” said I airily. “I’ll nip up the other side of the ship and get aboard. I can get hold of plenty of stuff in the pantry.”

“As if I should allow it for a moment. I forbid it absolutely,” and she brought her little foot with a stamp upon the rock floor.

I still edged toward the cave mouth, explaining that the danger was practically nil, though well did I know the contrary. Still a man can’t sit still to watch a particularly sweet woman starve, even if he has to risk a bit to bring her victual.

“I cannot stand the ignominy of starvation,” I assured her, “not to mention the discomfort.”

She came toward me with her eyes so sweetly appealing that I felt sick with temptation. “If you go,” she said almost tearfully—there really was a humid look in her blue eyes—“I shall simply die of fright. I won’t be left alone.”

I hesitated and was lost. She put her hand upon my sleeve, and looked up searchingly into my face. “Please, please, please, don’t go. I really am very frightened.”

Goodness knows what I should have done next. Probably taken her in my arms and sworn neither to leave her then nor ever again, regardless of Denvarre or any question of mere honor. But fate took matters out of my hand.

The brute above us gave a hiccough; I believe he meant it for a sneeze, but as a minor explosion of sorts it might have held up its head with cordite cartridges or an oil motor-car. Gwen, whose nerves were, as you may imagine, a trifle beyond control by now, gave a cry and fled into my arms, which opened of themselves to receive her. And so for a minute we stood silent and listening, while my pulses rioted within me.

After a moment or two we were aware that the fœtid odor of the great Beast was being overpowered by a resistless smell of sulphur. This was doubtless giving our friend a sore throat, and titillating his nostrils. I hoped devoutly that the unpleasantness of it would be too much for him. He snorted once or twice again, and then a faint steam began to rise from the depths, as I had seen it do in the morning. Far below us I could hear the faint lap of water upon the stones.

Then a horrible fear took possession of me. The water was rising, hot from some volcanic spring. Shortly it would gurgle out at our feet and flood our refuge. Then we should have the necessity before us of deciding whether we would drown—or perchance be parboiled—or step resignedly into the jaws of the Monster outside.

I looked fixedly at Gwen as these terrors hunted each other through my brain, and I suppose my thoughts shadowed out upon my face.

She turned her eyes to mine as I held her, looking questioningly at me, as if she would read my very soul. A sob and gurgle from the rising water sounded out bell-like and clear, moaning distinctly across the silence. I knew by the shudder that ran through her that she was realizing what must happen when it lapped up to us. Her face fell upon my breast; her hands rose tremblingly to my shoulders; so for a few moments we stood, and silence hung between us.

The white clouds of steam began to weave and whirl fantastically across the mouth of the cave. The warm, damp air played about us. The suck and splash of the waters sounded ever nearer and clearer from below. Above we could hear the wheeze and the occasional gasp of the watching Monster, and his feet moved restlessly, sending down showers of little stones into the abyss, where they no longer clattered into emptiness, but fell with splashings into the growing flood. Then a thrill pulsed through the rocks, and we could feel the sickening heave and roll of the earth as a new eruption shook the crater. In a second or two the roar of it came dully down to us, drowning the sound of the rifle shots which still pattered at intervals on the rocks, or thudded on that sensationless hide.

Finally the water rose to view, creeping with slow, silent tide up the rocks, gaining inch by inch upon the sides of the cleft. A wreath of steam hung mistily upon its surface. I bent and touched it with my finger. It was warm—about eighty degrees I should imagine—but not unbearable.

I stepped again to the cave mouth and peered up. The cruel snout still projected over the edge above, waiting, waiting remorselessly. As I watched the triangular head moved forward a space, and, turning sideways, looked down at me with hot, revengeful eyes. I stepped back into the shadow of the cave, and down flashed the head, hanging in eager, swaying motion before us, gloating for the moment when we should be thrust out to it by the rising flood.

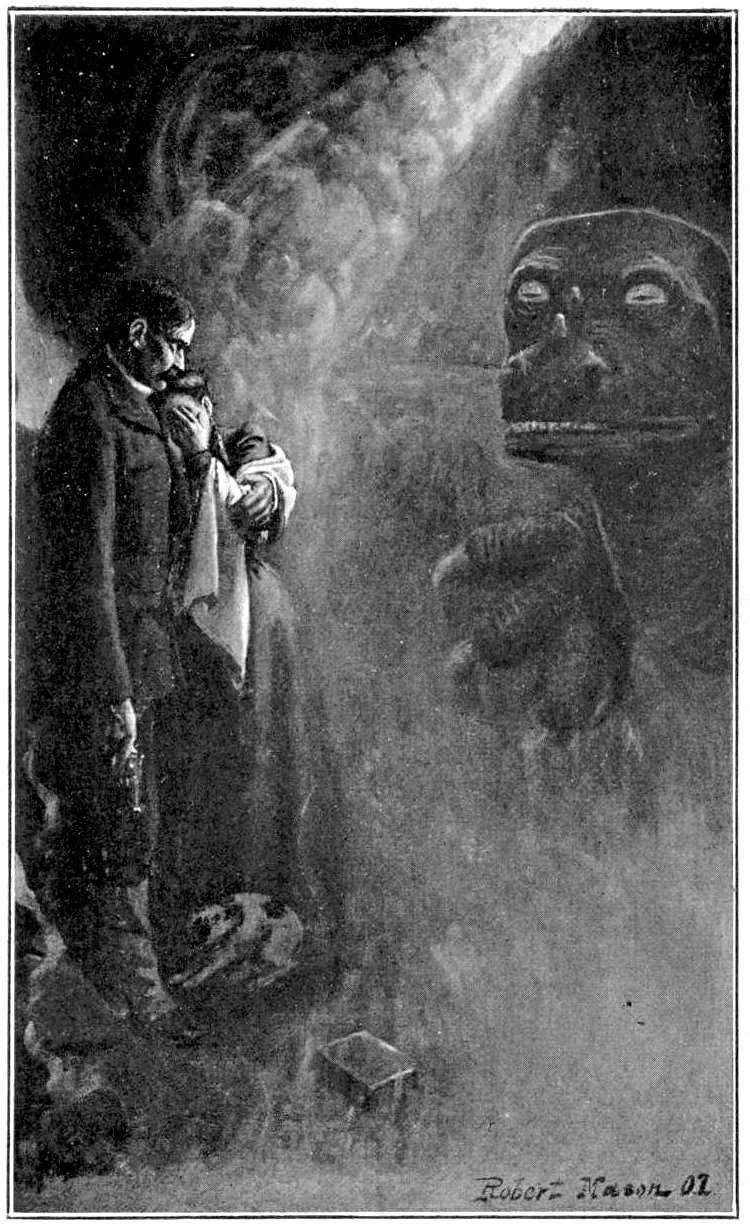

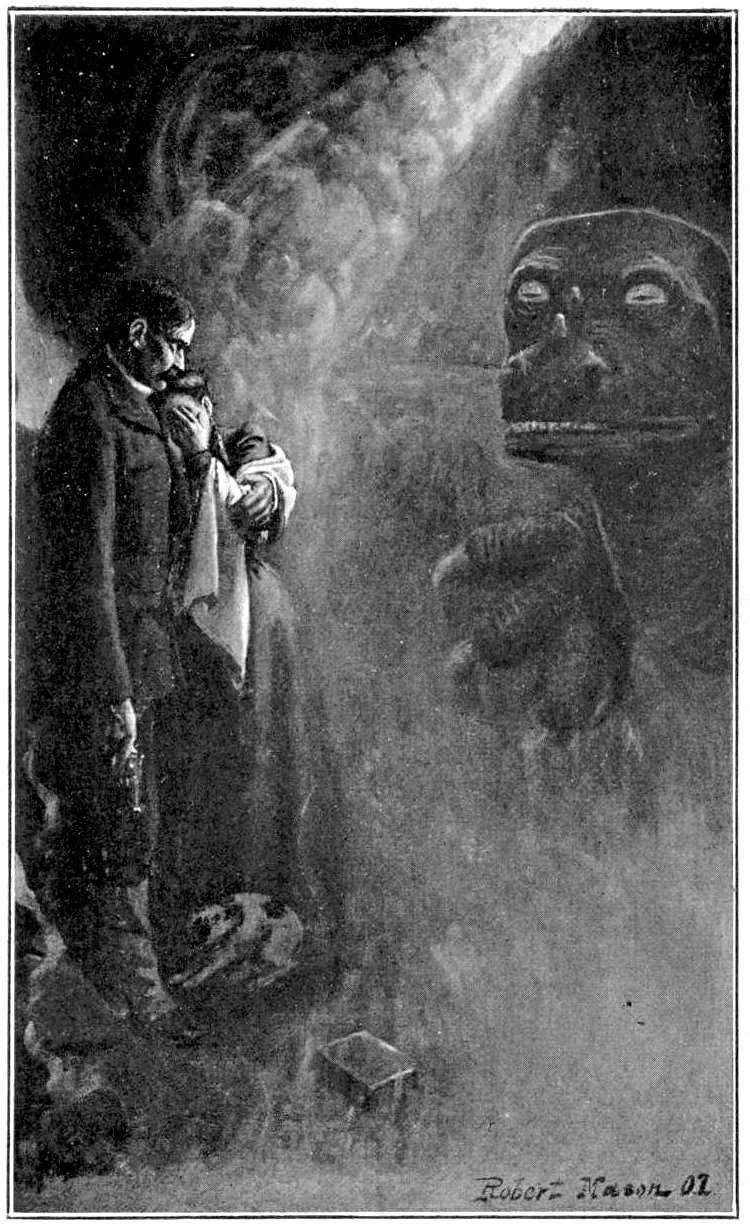

I slushed back to the end of the cave—the water was now at our knees—and took Gwen in my arms, shielding the gruesome sight from her with my breast. She drooped into my embrace again, trembling, but with a little thankful sigh for companionship in this last desperate pang.

“It’ll soon be over,” I said as steadily as I could, while my hand brushed her hair smoothingly. “Just a little struggle, and then a dream that carries you right across the border, and—and I shall be there to meet you. Do you see, dear?”

I had no right to call her dear, I know, she being Denvarre’s and not mine, but it was the last time, and, poor little soul, she wanted comfort for the last wrench. She looked up at me, and I could see that her lips were parched and dry, though there was a curious light shining in her eyes.

“Is there no chance at all?—are you sure?” she whispered, and for all the horror that was closing down upon us, a smile shone in her eyes.

“None, I fear,” said I; “but—but I don’t think it’ll be bad—people who have been nearly drowned say that——”

“Ah, I don’t mean that. Only I wanted to tell you before the end—I meant to tell you in any case, but it’s easier now. Vi only found out this morning that mother had led you to think that we had accepted those two—but—but it isn’t so. Lord Denvarre asked me, but I told him I didn’t think I possibly could—only—he wanted me to wait six months and see—and then we met again, and—I knew—then——” But my lips upon hers stayed her, and my arms went fiercely about her again.

“My darling, my darling,” I cried, “and I thought you’d forgotten me utterly, and taken Denvarre for all he could bring you. And now, sweetheart, now—oh, my God,” I groaned, “what can I do, what can I do?”

Her voice was quite steady, and she leaned forward to put her face up to mine. “Then you still want me, dear,” she whispered. “Well, I’m yours till—till the end,” and a tiny sob shook her voice for a moment. “But I want a gift from you before we part, my darling,” and she touched my cheek with a little soft caress.

“A gift?” I stared back into her eyes, devouring with hungry gaze the sweet face that was mine, only to be lost to me again.

“Yes, dear. You have your revolver.”

“IT’LL SOON BE OVER,” I SAID.…

I thrust her back from me wildly. My God, how could she ask it? I, to send the bullet into that dear heart that beat for me. I, to give her death, who longed with every passionate impulse of my being to give her life, who would have perilled not only my unworthy body but my very soul to save her pain. The thought of it was more than could be borne; the doing of it—Merciful God! it was impossible.

“Please, my darling. I should only struggle when the last moment came, and fight out into his jaws.” She pressed back close to me again, looking up at me with a pleading that was terrible. “Just one embrace, my own, and then——” and her hands rose round my neck, and for one delicious instant her dear lips pressed passionately against mine. Then, with a little triumphant smile she drew back, and repeated quietly, “Now, dear.”

The water was at my shoulders, and it was only by holding Gwen tightly to me that I kept her face above the surface. There was but a bare three inches between my pistol hand and the roof. I looked at the cartridges with some faint hope that they might be wetted, and that this last terrible duty might be yet taken from me. But the brass cases had held only too well. I raised my revolver, pointing it downward, and looked into those dear eyes. Her eyelids drooped as the steel barrel shone, and I felt her fingers tighten upon my arm. The water was at my lips, but with one supreme effort I raised her to me. One last look into the dearest face in all the world—one last kiss—one touch of that golden hair—then——

Crash—crash—crash—outside was a grating roar, and caught by the rising tide the ship surged forward. The bulge of it swung against the cave mouth, and in an instant caught and gripped the pendant neck, sawing and grinding its flesh against the jagged edges. The prisoned head in its agony beat frantically against the surface, and the water shot right and left in angry ripples as the breath of the Monster’s scream burst upon it.

The revolver dropped from my hand. I snatched Gwen to me, and dived into the hot, turbid flood—down beneath the struggling head, down beneath the ship’s keel, out into the warm stillness of the cleft beyond.

Gasping and choking from our sudden immersion I dragged my darling over the edge, and half-led, half-carried her up the rocky slope, leaving a long wet drip upon the granite. The enraged and baffled yelling of the captured Beast rang out piercingly among the cliff echoes; the lashings of his great tail smote upon the empty hold of the ship as upon a drum. In his vain attempts to draw his neck from the trap he drove and spurred at the boulders frantically, and the clatter of his long nails upon the pebbles sounded like the scratchings of some monstrous cat.

Our clothes were sodden and heavy, and our nerves unstrung from terror and excitement. We were in no condition for a swift escape. My own state of mind I can in nowise describe, such a confusion of fright and ecstasy raged therein. Firstly, the horrors of a hideous death still hung over us, though for the moment passed by. My pulses still tingled with the sick despair of that last terrible moment. Death had been my betrothal gift to my love—death to save her from agony. Another second, and she would have received it at my hand. Thank God that there are few who can realize the æons of torture that swelled into those few instants of good-bye. Death was still at our backs, and might follow hard upon our footsteps, but I was so uplifted in the knowledge of my darling’s love, and in learning that no point of honor stood between us, that I scarce gave a thought to remembering that we might yet stand together in the Valley of the Shadow.

Up the slope we toiled, and very like one of those terrible hills that we climb in dreams did it appear. Gwen clung to me desperately, her dear eyes hunted and shining with affright. Her knees trembled—she strove to run, but her dripping skirts caught her limbs and made her stumble.

Still up we reeled, the pebbles spinning from our unsteady feet, the smooth rock silt churning to mud upon our shoes. From above came cries of encouragement, and from the heights I seemed to see dark forms speed down toward us. Another crash echoed from behind. I threw a quick glance across my shoulder. The Racoon was slanting back from the cave mouth, and the Monster was free. I saw him turn and crawl slowly from the pool in which the ship was beginning to right herself and sit swan-like.

He lifted his head, and I saw the blood flow in streams from his gashed throat. It steamed as it made puddles upon the cold rocks. He sniffed the breeze. Then his evil eyes settled their stare in our direction. The huge body began to waddle and slide toward us.

I caught Gwen up in my arms and fled upward, terror thrusting me on. She gave one gasp of protest; then she settled into my embrace with a little sigh of relief as she nestled to me. So the race for life began.

I ran almost unseeingly, the great pulses throbbing and thrumming in my bosom. Now and again I stumbled; once I nearly fell. Gwen’s arm came with a jolt against a boulder top. I cursed my awkwardness, hurrying on and trying to pick my way amongst the great, loose lumps more carefully. Some rubble gave beneath my feet. I rolled over sideways; somehow—though how I can’t say myself—I managed to fall upon my elbows and save my burden from harm. I rocked up to my feet, and saw as in a dream the cliff-foot two hundred yards away, and upon it the forms of men who ran toward me.

I turned my face over my shoulder again. The Brute was a short half-furlong away—his tongue lolling from his wide expectant jaws. He strained his neck toward us, his eyes aglint; he seemed almost to trot rather than waddle in his greedy haste. Determination and despair drove me forward as with a goad; I panted with the horror of his oncoming.

Above me sat Garlicke, rifle in hand, breaking the clean outline of the ridge against the sky. The rifle was silhouetted thin and delicate as a needle against the brightness. A spurt of blue smoke burst from the muzzle, and the crack of it rang across the hollow. I heard a thud as the bullet struck the mass of hungry desire behind me, and glanced again quickly, hoping for effect. A red weal shone upon one of the horny eyelids. He stopped, blinking stupidly, and half-stunned by the shock. But the ball had not penetrated, and with a puzzled swinging of the wounded neck he resumed his scrambling, ungainly gait.

Still a hundred yards, and my eyes grew dizzy. A red mist seemed to close upon them, which, lifting now and again, showed me surrounding objects defined as on the slides of a magic lantern. My breath rasped with such a wheezing whistle that I looked wonderingly to see whence the sound could come. My arms were like wire ropes, strained to the breaking. My legs shuffled painfully under me. I felt the strength going out from me as water leaks from an unbunged cask. The sound of Garlicke’s shots struck fainter and fainter upon my ears. I stumbled again, and only saved myself from plunging forward by an instinctive straightening of my shoulders. The sunlight was shadowing to a night—a black darkness that could be felt.

Then, dimly, a familiar voice broke upon my ears; I was conscious of a hand seizing my arm; of some one struggling with me for Gwen. Yet, thought I, we will die together. Then the friendly hand, leaving this useless striving, dragged me forward; behind me some unseen power was thrusting me with mad shoves up the Titan steps of the cliff face. Suddenly came clearness of vision, and I knew Denvarre and Gerry, who were hauling and jerking me up the crevices of our rock of defence. Gwen was still in my arms, and below, the great monster scrabbled at the cliff-foot, reaching up his neck in raging, ravenous disappointment.

So, Denvarre dragging and Gerry butting like some benevolent goat, from niche to niche I stumbled with my burden, the little stones rattling down in their thousands upon the Beast below. Upon the top I staggered forward into the shelter of the tarpaulin, and laid Gwen down upon the rocky floor. Then, in the sudden impulse of her love, and in her revulsion from that great dread, she flung her arms about me as I stooped over her, and before them all kissed me on the lips. And who was I that I should not kiss back once and again?

So my love and I came to an understanding, and sealed our betrothal as the shadow of death passed from us—passing as a cloud when the breeze is strong and out leaps the sun; while above us the mountain still belched fire and molten stone, and below the Beast prowled, and sought hungrily for our blood. And I take it that never have man and maid plighted troth in stranger circumstance.