CHAPTER XIX

A WONDROUS BREACHING OF THE WALL

A good man all through is Denvarre, as I said before, and like a good man he took the failure of his hopes. And they had never been anything more. For as he explained to me, when we had changed our dripping clothes and joined the others on the cliff-top, he had no knowledge of Lady Delahay’s very distorted rendering of the situation. And he shook my hand and looked me straight in the eyes, and then, like the gentleman he was, went away to leave my sweetheart and me to say all we had to say to each other behind a ledge of rock that screened us from the others. And he took with him my unstinted admiration and esteem.

My future mother-in-law was in no condition for the exchanging of ideas or reproaches. The horrors of the situation crowded her understanding, leaving no room for such trivialities as the arrangement of her daughter’s welfare. Apathetically she took the plain statement I thought it only my duty to render to her, making no remark thereon save that “Nothing mattered when we should all be dead before the day was out.” And to this pessimistic view of the situation we had perforce to leave her, while we all waited for what should betide us at the hand of fate.

A RED STORM OF LAVA DASHED IN A CLOUD OF STEAM TO THE FAR END OF THE LAKE

In the corner apart Gwen and I held each the other’s hand, and sought each other’s eyes. And in the bliss that was mine I thanked God, nearly sparing a blessing for the great Beast who still prowled below, for how but for him should I have come into my kingdom of delight? So in happiness that even the great smoke pall could not overshadow we sat to watch the day die, and the blood-red glow of the mountain wax scarlet on the dark cloud above us, while the pulse of the undying fires vibrated across the heavens after each succeeding roar and shudder of the melting rocks.

As we watched the travail of the hills, across the edge of the crater where it was lowest in the lap of the peak, a thin line showed. Faint it was at first, then thickening to a broad scarlet, where the range of ringing rocks dipped lowest. For seconds it hung there, a red bar of palpitating, blood-like flame. Then with a roar it broke over the barrier and swept on headlong down the spur of the hill, engulfing the smaller rocks, and laving the bases of the larger ones that stemmed its current island-like.

After the first mad burst the roaring spate of fire slowed on a slighter slope; then rolled massively, grimly down upon the glacier head through the vale of granite. As the lava drained to the bottom level of the rent in the crater the flow lessened. Finally it ceased. Ere half-a-mile of the distance between the orifice and the glacier had been covered the crimson glow began to fade. The surface of the flood dulled to a dark crimson, then to a living blackness as of velvet. The crest of the advancing flood sank down sluggishly and stayed, its bosom curving menacingly, the advance guard of an army irresistible.

A flaring pillar of flame-dyed, guttering stone shot skyward again, the splashes of it thudding about us heavily. One molten lump, stiffening as it fell, smote on our tarpaulin roof, slashing through it to the stone floor. A shriek went up from Lady Delahay as she shrank back from its still living glow, and the tarpaulin burst into sudden flame. A dozen willing hands tore it down and wrapped it together, smothering the fire in the folds. Poor little Fidget—utterly cowed by terror fast following on terror—came slinking toward me, and nestling in between Gwen and myself, hid her little nose deferentially in my sleeve. My darling gave her a little friendly pat, and I cuddled the little dog gratefully myself. But a shudder followed fast on the caress as I thought of what might have been when she had been kicking and screaming in that death-trap in the cleft.

We peered down at the Beast. He was still rambling restlessly about, snuffling now and again at the cliff-foot, aimlessly pawing and snatching at the boulders that banked the rock face. Once just below us, where the sheer crag melted into a more slanting angle, he rose clumsily upon his hind limbs, leant forward, and stretched his head toward us, pricking out his long tongue. As it licked across his lips the jag of broken tin flashed redly in the glow, and we could hear it grate as his teeth closed.

His head reached up to within forty yards of us as he swarmed against the cliff, and Garlicke aimed carefully for his eye. The bullet only grazed the unscarred eyebrow, giving it a curious uniformity with the other one. The brute merely blinked impatiently as the ball thudded on the shell-like lid, but did not twitch a muscle. As it splayed out its feet on the bank of loose stones, seeking purchase to strain higher, the rubble gave way, and it rolled back with a thump upon its side. Its green belly shone a loathsome pink in the glare from above, and for a moment it lay prone, its great legs kicking convulsively. Then with an effort it righted itself, and crawled sulkily away to resume its sentinelship at the cliff-foot. It continued to ramble to and fro unceasingly, casting ever greedy eyes at us, the hideous snout lifted to the breeze, the long tongue lolling from between the yellow teeth.

Down in the hollow a growing sheet of water spread. On it the ship floated lopsided and aimlessly. Long widening ripples welled from where the cleft was submerged, and a steam-cloud was hazy upon the surface. The hull was all untrue upon its keel with the shifting of the ballast, and as the ripples swung her, drifted in slow circles. With her lost topmast she looked like nothing so much as a wounded wild duck. The fire glow gave the increasing water the effect of blood issuing from a wound in the bosom of earth. On it were reflected crimson throbs from the arch of ruddy fog; they were as pulses across an opened vein.

Another quiver rocked our pyramid of granite, and the glacier was riven across. The following roar gushed down to us deafeningly. The lane showed dark and mysterious across the ice-field, clean cut as by an axe blow, and this new-made cañon ran with scarce an obstacle nearly to the foot of our refuge. We seemed to get a vision, swift and fleeting as a lightning flash, of the hidden mysteries of the ice. I could have declared I saw the yellow facade of the buried temple show up against a black background of rock. Then as the flying lava sank back again into the bath of fire, darkness closed over this half-seen apparition.

Once again the red bar glowed across the dip in the crater brim. For one tense moment it hovered, and then crashed down upon its dying forerunner, covering it anew with living fire. Along this smoothed path it rushed headlong, leaped down from the lava crest upon the stones, and rolled with measured grandeur down the groove the earthquake had riven. Blocks of ice, fallen from the glacier sides, lay in its course and were swallowed in a moment. Like the roar of a bursting shell the steam bubbles smashed to the surface, and floated up in white circling clouds to lose themselves in the fog above. Unhalting the torrent ran, engulfing all before it; stones, ice, and the rock itself disappeared. Then in slow-growing blackness it stayed, sank and died, even as its predecessor. But this time the wave reached to the end of the fissure, and the heat of it beat up to us, lapping us in a bath of sultry, stifling air.

The Beast shifted his sentry walk uneasily, stretching out his neck toward the lava wall, and snouting at the warm draught suspiciously. For a moment he seemed to waver. His nostrils dilated curiously. Then he glanced toward the rising lake, and we thought he would give over his seeking for our lives. As he hesitated, now looking lakeward, now peering up to us, another crash resounded from the mountain. Like the tearing of a sheet of paper the glacier cañon split further shoreward, and opened beneath his very feet. Half his bulk rolled into the cleft thus riven; his tail and one hind limb disappeared. Slipping and spurring frantically he managed to support himself on his huge elbows, but lost ground with every rock of the shuddering earth. The cleft yawned, then half closed again. Thus as in a vice he was held, his leg and tail mangled in the nip of the fissure. He looked like some stupendous stoat caught in a gigantic gin.

The bellow of his agony pierced even above the thunderous roll of the mountain. The blood spurted from his sides, bathing them in a darker tinge than the flame glow. His fore-feet beat and thudded on the stones, sweeping them into ridges with the convulsions of his agony. He swung his neck across his shoulders, tearing rabidly at his wounds.

The sight was almost too much for human eyes. Gwen had already buried hers against my coat. The breathing of the sailors behind me grew stertorous, as their chests rose and fell in unconscious sympathy. Speech was taken from us by a very paralysis of horror. But worse was to come.

The fiery matter that fevered the volcano burst forth again. Again the mountain shuddered, belching forth its flames. Down the dead waves another living torrent rushed, roared in the deep channel through the glacier, and foamed—yes, foamed—into the widening split. A scream, anguish-born and like the crowded wails of ten thousand souls in torment, rose from the prisoned Beast. A pungent, choking smell of roasting flesh rose up to us. Then the red tide flowed on over the charred carrion, and burst asunder again; a gout of steaming gas shot up, sole remnant of the tissues of that enormous carcass. The stream touched and laved lightly at our refuge. Then slowly it dimmed, and the velvet surface grew up on it again. The current halted and grew still. Its force was spent.

The heat beat up to us scorchingly. We felt, but saw it not. Our faces were averted, and nausea had us by the throat. As the great Beast had died, so might we come to die, and that right soon. The realization of the matter was more than we could see and not blench. For some half-minute no one spoke, and dread hung over us thick as the cloud of cinder dust that filled the sky.

As I raised my eyes again to look on the things of earth, a broad line showed across the seaward cliffs that hedged us in. It increased visibly as I stared at it, and I knew that again the cliffs were rending between the sea and the growing pool. I leaned across and touched Janson on the shoulder, pointing silently. As he too caught sight of the rift the light of hope grew across his haggard face.

“If it cuts down to the sea——” he muttered, glancing to where our ship and the little launch wandered masterlessly about among the steam wreaths. He turned to me and pointed to them.

“Let’s get aboard, my lord. It’s only a hundred to one chance, but it might widen and give channel. Here’s only quick roasting, at any rate.”

“How about the propeller-shaft?” I queried sadly. “We shan’t be able to get steam on her.”

“That’s no matter,” he said, shaking his head impatiently. “We can get steam in the launch for a tow, or if that takes too long, ten oars in one of the boats would shift her, lopsided as she is.”

“Who’s to board her, Mr. Janson? It means swimming.”

“I can if nobody else will, but I’ll give Rafferty the job. He’s a fine swimmer,” and he beckoned to the boatswain.

“Board the launch,” quoth Janson to him curtly, “and bring her ashore.”

Rafferty made no remark on this terse order, but slipped quickly down the ledges that led to the rocks below. He kicked off his boots, dropped his jacket upon the stones, and poising his hands above his head, sprang like a dart into the still pool. There was scarcely a splash as he struck the surface, but he rose almost instantly in a circle of foam, while a shrill yell of agony burst from his lips. He threshed desperately back to the shore, still screaming horribly.

Howling and cursing, he flung himself upon the stones, and, oblivious of all considerations of modesty, tore off his clothes. He apostrophized every saint in the Catholic calendar. He squirmed, he bellowed, and believing him struck with sudden madness we raced toward him, utterly at fault to find explanation of this sudden explosion. But as we drew near our eyes soon found a cause.

The unfortunate seaman was red as any lobster. His skin was blistered and parboiled. It hung, as he himself explained in no uncertain voice, “in tathers and shtrips.” The waters of the rising lake had scalded him horribly.

We caught the unfortunate seaman as he wriggled upon the cool stones, and wrapped him in our coats. One of the men ran back for our blankets, nothing, as I well knew, being so dangerous for him as exposure to the air. What he needed most was thick coverings and oil. But, unfortunately, the whole stock of the latter was aboard the ship.

In this extremity the long black bulk of the stranded whale beneath the cliff caught my eye. It was no time for discussion. Gerry and I snatched up the kicking mariner, and bore him loudly complaining toward the carcass. We hacked great greasy lumps from its reeking sides, and then, as the blankets arrived, packed the victim tightly in this carrion, twisting the folds of blanket round the layers of blubber. So, muttering condemnation on all and sundry, and sniffing most melancholiously as the stench of the putrid wrapping filled his nostrils, we set him down, while we devised other means of reaching the ship across the steaming lake.

The launch was now only about sixty yards away, turning slowly as the ripples rose from the centre of the pool. One of the sailors produced a ball of string. To one end of this we tied a sizable pebble, and Gerry, who is a noted man at throwing the cricket ball, managed after some half-dozen attempts to land the stone in the bottom of the boat. Careful tugs brought her ashore, and in less than a minute we were aboard the ship.

I ran forward and knotted a loose rope to the foremast. Then, taking the slack, we jumped back into the boat, and bent our backs to the oars. Ever so slowly the ship got way and followed us, till the grating of the keel against the shallows told us she could come no further. We looked at the cleavage of the rocks. We saw with gladness that it had widened yet more, for the blue horizon line of ocean shone distinct across it, and the peaks of the nearer bergs jutted up into the vista. The others who had watched us from the heights now began to descend the granite stairway.

In straggling procession, the sailors weighed down with our surplus stores, they joined us as we strained upon the rope. The ladies were quickly ferried across the few yards between the rocks and the ship, and some of us tossed the various impedimenta aboard, while half-a-dozen ran back up the rocks to collect all leavings. Then, dumping everything anyhow upon the deck, we got a strong crew of six in one of the boats, hoisted the launch aboard, and gradually got the bows turned cliffward.

The waters were still gushing up and widening upon the basin, the circling eddies helping our towers as they dragged us tediously toward the cleft. The shocks from the mountain came with greater frequency, making the pool shiver into tiny surges that fled across it, to break in ripples on the further shore. Another of the peaks toppled and fell with a resounding crash.

The fissure began to disappear amid the cloud of low-hung steam, and it was with difficulty we steered our course for it. A sudden outcry from the boat that strained ahead made us aware that we were forging with all the powers of six stout oars straight at an opening that was yet a dozen feet above tide-level. It was only by the smartness of the boat’s crew, who doubled sharply in their tracks and snatched a rope flung to them from our stern, that we escaped inglorious shipwreck. They tugged lustily in the contrary direction and managed to stop the ship’s way. Then, having us more or less motionless, they rested on their oars, and we floated aimlessly, waiting further developments, for the fissure still widened.

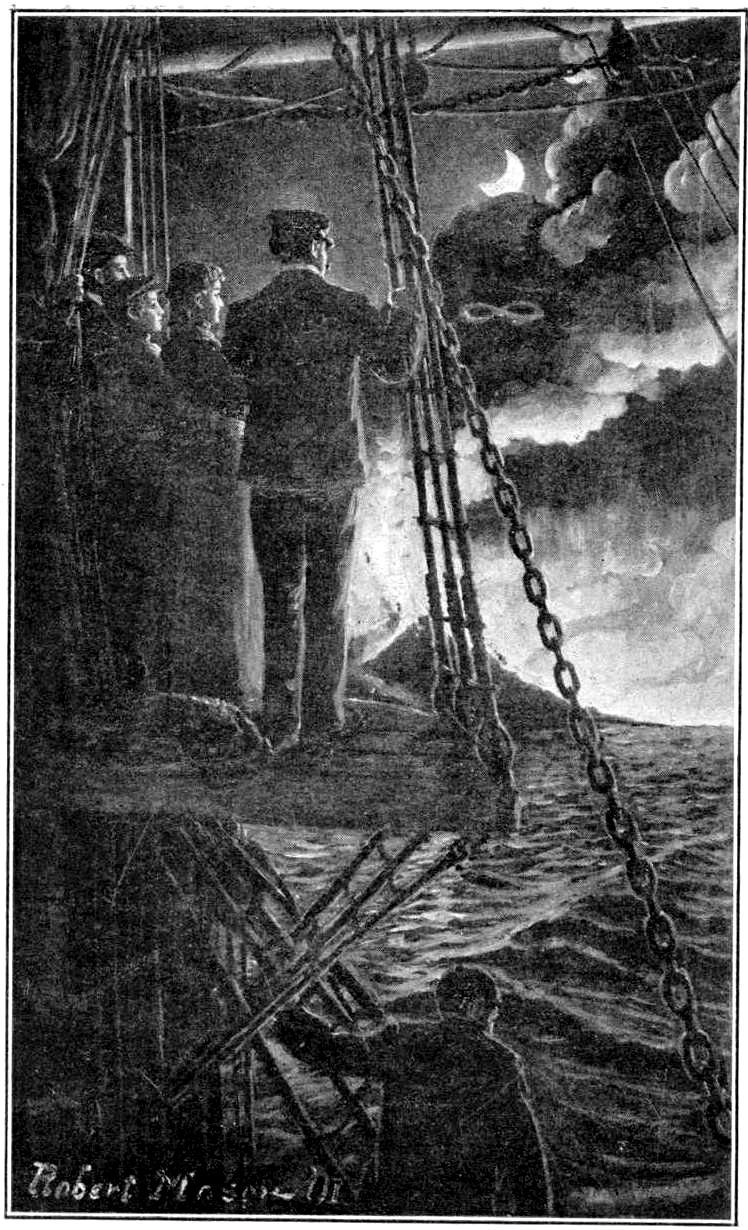

We were silent, for the awe and anxiety of our position kept us tongue-tied, and every one was on deck. The sailors fidgeted up and down, now and again shifting perfunctorily some of the heaped confusion of the decks, but stopping every minute to gaze inquiringly at the peak, as roar after roar and shock after shock swept down from it. We were like malefactors awaiting execution, but hoping desperately against hope for a reprieve.

Then a thunderous boom, fifty times louder than any that had preceded it, broke from the bosom of the hill. The pinnacles swayed, tottered, and bowed earthward; not one but was swept from its base. A red storm of lava surged boiling over the crater brim, swelled in a torrent down the channel through the heart of the glacier, and dashed in a cloud of steam into the far end of the lake. A vapor mist, impenetrable as a desert sandstorm, closed over the waters, but ere it fell we saw a huge threatening wave uprise and swing across at us in fury irresistible. Behind it was all the impact force of the fiery mass, but long ere it reached us the fog rolled down and shut us in in its warm gray veil.

A rending crash broke from the cliff in front, and the cold, hungry ocean came clamoring through, beating upon the outcharging tide. For some furious seconds our ship plunged and reared among the fighting billows like a restive horse. Then from the boat came a cry as the pursuing wave reached her and flung boiling spray upon the men. Like a toy she was raised and flung toward us. The wall of water struck with a thud below our stern, and thrust us, bow forward, at the gap. Swifter than paddle or screw could have borne us we sped upon the crest, driving straight into the new reft opening.

A gasp went up from every throat, and not one of us but breathed a prayer. Two seconds more and the dark walls were flashing by on each side. Then with a dying effort the great wave flung us far out into the ice-bestrewed main, diffusing itself up the long lanes of floating berg, roaring and clanging amid the splinters of the floe.

Spinning on yet before that mighty impulse, lopsided, with ballast adrift, with fore-topmast gone and propeller-shaft broken, we fled forth from our prison, dragging the boat astern with her bows out of the water, and from boat and ship alike went up a mighty cheer of deliverance as the great crags faded into the steam-cloud behind us. And so did we accomplish our marvellous escape.

As the great surge sank to ripples, we sprang to work, full of the energy of relief and gratitude. Some set to right our littered decks, some descended into the hold to replace the shifted ballast, while Eccles, debarred from work by his broken collar-bone, stood over his subordinates and admonished them with many a good Glasgow expletive to seek drills to rivet a collar on the split propeller. Rafferty from between his oily compresses roared curses and commands at the deck-hands, and all, crew and passengers, were busy as best they knew how. And behind the deck-house my love and I found time to seal with a kiss the promise of new life that had had its birth under the very Shadow of Death.

The red glow of the fire-pillar was beginning to pale into the tints of dawn before we had cleared our deck into any similitude of tidiness. All night long we toiled, relieving each other in crews of eight at the towing. For the heat ashore made the breeze beat landward with aggravating steadiness, and but for persistent effort we should have drifted back on to the sheer cliffs of the wall, and pounded our timbers into matchwood on its iron face.

So wearily the oarsmen toiled and drew the unwilling ship by slow by-ways amid the herding pack-ice. And down in the engine-room Eccles sat to swing his sound arm upon the gearing and spit imperious blasphemy at his underlings, who drilled and drilled again with stiffening fingers, while forward the carpenter wrestled with a spare spar to raise anew a topmast. Both on deck and below Rafferty’s nimble tongue reached and drove the lagging crew.

Finally with morning came a fair breeze off the land, and getting sail upon the mizzen we lurched easily along, and the weary towers came aboard, full of thankfulness and dropping with sleep. Then leaving two volunteers to steer—Janson and Parsons to wit—we one and all sank down upon our berths and slept as only those sleep who have labored through four-and-twenty hours of surpassing terror and excitement.

It was late in the afternoon ere I reached the deck again, washed, changed, and looking rather less like a sweep’s apprentice than I had done twelve hours before. Gwen was pacing to and fro forward, and delicious it was to watch her from the companion, and to note, with all the inward glow of love’s proprietorship, the golden curls flutter against her white forehead.

She turned as I stepped out into the sunlight, and came and gave me good-morning with such happy shyness that I entirely lost my head in the exuberance of my feelings, and took thrice as much as I was offered. Which sweet felony I might have continued in spite of my lady love’s admonishings, but for the audible titterings of Gerry and Vi, who were conducting a similar function on the other side of the deck-house.

It was not an altogether cordial interview I had with Lady Delahay, but on my part it was a very determined one. And she was in no condition to face me boldly. The stress of the last few days had worn her down, and she made but half-hearted defence of her devious dealings with me, and after my explanation that the dignity of the Heatherslies was not to be kept up on an Irish rent-roll alone, was almost kind. At any rate she saw that further opposition was useless, and wisely considering that it was well to agree with her son-in-law while she was in the way with him, gave a consent that was not entirely a grudging one. As yet the desperate proposals of Vi and Gerry remained untold, and her temper had not been strained beyond its furthest limits. So I retreated with the honors of victory thick upon me, and in great peace my love and I went back to sit together behind the deck-house, and what we said to each other is no one’s concern but our own.

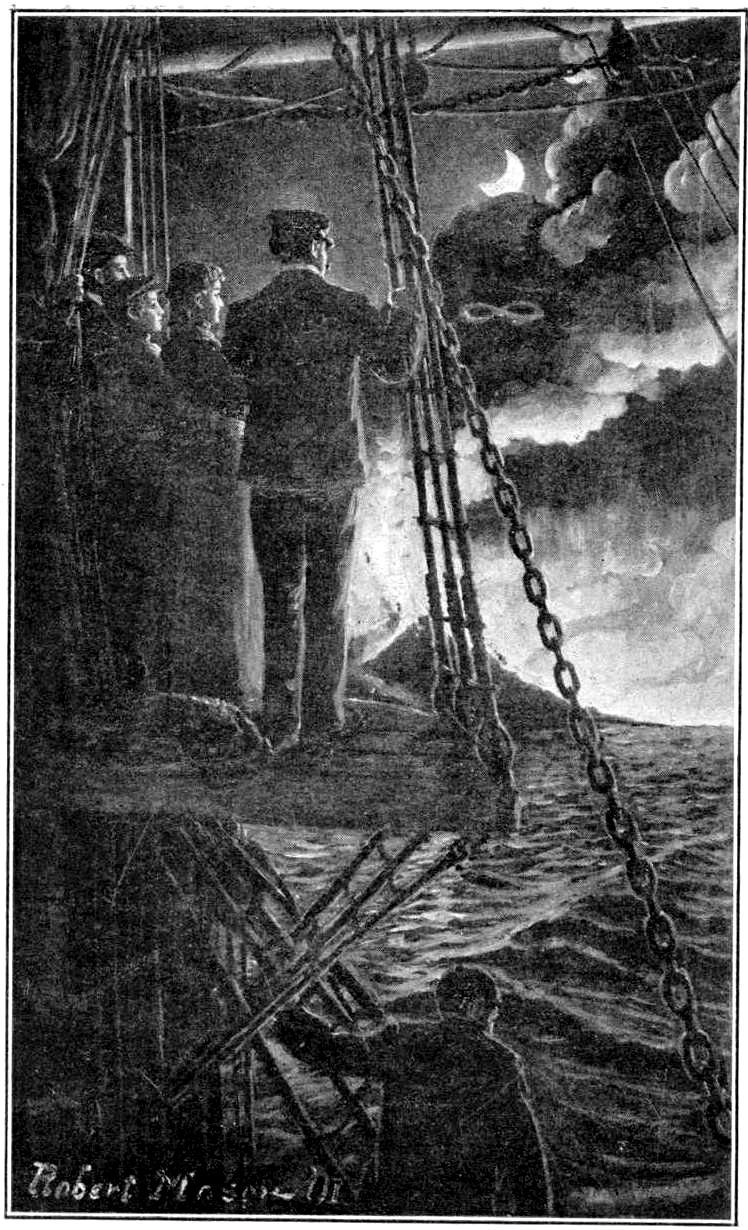

For three days the flap of a two-knot breeze was upon our canvas, and we met occasional berg. But on the fourth morning we woke to an ice-free horizon, and to the hissing of steam in the boilers; this welcome sound being soon followed by the sight of a pale wake of screw-churned foam. Neither Eccles, nor any man who called him master, had had four consecutive hours of sleep in the last eighty, but thanks to this and to his Scotch determination, we thenceforward swept our way regardless of resisting winds. Ten days of half-speed, lest we should strain our new-spliced shaft, brought us through constant sunshine to within sight of the Falklands.

With the R. Y. S. pennant afloat, and black smoke curling from our funnel we breasted the billows into Port Lewis. As we drew near the land we were aware of a gallant ship standing out toward us; she too had fires new-stoked, and her cutwater spurned the foam. At her peak the white ensign floated, and we knew her for a man-of-war. Suddenly upon her decks commotion was visible, and the jangle of her engine-room bells came distinctly across the stillness. As she slowed, a stentorian hail came from a gesticulating figure on her bridge.

“Racoon, ahoy! Is it yourself then, or a new Flying Dutchman? In the name of heaven, m’lord, how did you get away?”

It was poor old Waller, and across the intervening sea-lane his face showed white as the lashed hammocks he stared across. His eyes were starting from his head.

A cheer went up in answer from our assembled crew, and joyously I bade him come aboard to hear our news. In three minutes he was on our decks, exchanging heartiest of handshakings with us all as we pressed round him, and pouring out question on question as he surveyed the ship again unbelievingly. I left him to the care of Gerry and Denvarre, while I attended to the blue uniformed naval captain who had accompanied him. This individual I could see was under the impression that Waller had grossly and impertinently deceived him with a cock-and-bull story of our sad plight in the desolate regions of the South.

I gave a hasty résumé of our adventures, leaving detail till the evening, which we spent with the man-of-war’s men in much jollification. Waller had been fortunate enough to arrive two days before us, and to find H. M. S. Bluebell paying her annual visit of inspection. Her gallant captain had promised to start directly Government stores were landed, and this promise we had found in the early stages of fulfilment.

We pledged this good purpose in champagne, and gave him thanks worthy of the accomplished deed. In the morning we coaled anew, and from the warship received help of engineers and artificers, who strengthened our patched propeller and battened down more firmly our ballast.

In the evening we parted with much esteem and desire for future foregatherings—we to turn northward and home by the south seas, the Bluebell setting her course for Buenos Ayres.

As the day died in the crimson of the sunset, my darling and I stood beside the taffrail and watched the ruby glories fade. We had just interviewed Lady Delahay on behalf of Vi and Gerry. With artful devices had I pictured the latter’s probable career in his profession with my influence at his back, and desperately had I exaggerated the possible worth of his share of the Mayan treasure. Denvarre, too, had magnanimously promised that the whole patronage of the family should be exerted to gain him attachéships and like lucrative posts. The result had been a tardy and unwilling, but official, benison of Gerry’s aspirations, and in the stern the young couple sat hand-in-hand with the more or less complacent assent of the lady’s mother.

So in perfected content my love and I stood together in the bow, and saw the sun sink into the main and the stars rush out into soft splendors above us. A thousand miles behind us were the terrors of the land of fire—terrors forgiven, in that they had knit our lives and now loomed shadowy through a mist of happiness. Our prow was pointing to the islands of eternal summer; and in our hearts love’s endless summer reigned.

THE END