CHAPTER 9

DEMITRIEV HAD NEVER BEEN VERY interested in archaeology, especially that of the Mayas and Aztecs, peoples who in his eyes had not had the strength to resist a small band of Spanish Conquistadors. He was more interested in modern history, which he had however always seen from a Russian point of view, expansionist, in the 19th and 20th European tradition.

It was Anna Basurko’s business card that had stimulated his sudden interest in archaeology and her link to Fitznorman, a Parisian art dealer. The other thing that puzzled him was another business card, one that he had not first remarked when he emptied Simmonds’ water sodden wallet, it had stuck behind that of Anna Basurko's in the water. It belonged to a certain Jean-Louis Favre, a Customer Relations Executive at a company called Ports Francs et Entrepôts de Genève, in Geneva, Switzerland.

Demitriev was a trained intelligence agent. Officially he was a counselor for economic affairs at the Russian Embassy in Mexico City, the usual subterfuge employed in diplomatic missions for intelligence agents. He belonged to the GRU, one of the successors of the KGB, specialised in military and related affairs. His work covered a broad spectrum of interests in the Caribbean zone, from Venezuela to British interests in the Caribbean and in general Mesoamerica.

It was only when he learnt that Russians like Yuri Knorozov and Anna Proskouriakoff had played key roles in the deciphering of pre-Columbian scripts did his interest pick up. He, like all agents of the Russian state security apparatus, had been trained in codes and the discovery of Knorozov’s work spurred his interest, who according to legend had as a Red Army colonel discovered a Maya Codex in the burning ruins of the Berlin Library during the Battle of Berlin at the end of World War II.

The Maya and Aztec cultures were the products of three millennia of pre-Columbian civilisation and the Maya had developed the most elaborate writing system of Mesoamerica, making it one of the most outstanding civilisations of the New World.

Like Pat Kennedy, Demitriev had asked why so little literature remained of such brilliant civilisations, the answer lay with the Catholic Church, which saw the native population as ‘too much a child, too much a slave, too little a man’.

In its zeal to convert the conquered peoples to Christianity it destroyed Aztec and Mayan libraries that contained countless books, some hundreds of years old, the cultural soul of those civilisations—religion, mythology, medicine, history, agriculture and astronomy.

Amongst those that led this campaign of destruction was the friar Diego de Landa Calderon who was born in Cifuentes near Guadalajara in 1524. At the age of 16 or 17, he entered the Franciscan Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo. In 1549, he left for the Yucatan, where over the course of the following decade he rose to become head of Franciscan Order in the Province.

Compared to the gold found by Hernan Cortes, the Maya possessed another treasure which Landa described in his history Relación de las cosas de Yucatn (Yucatan Before and After the Conquest):

‘If the number, grandeur and beauty of its buildings were to count toward the attainment of renown and reputation in the same way as gold, silver and riches have done for other parts of the Indies, Yucatan would have become as famous as Peru and New Spain have become, so many, in so many places, and so well built of stone are they, it is a marvel; the buildings themselves, and their number, are the most outstanding thing that has been discovered in the Indies.’

The success of the Franciscan can be judged when converted Maya children willingly betrayed their own fathers, denouncing them to the friars, accusing them of idolatry and orgies. Then, under the orders of the monks, they commenced the destruction of the idols, including those of their own families.

In 1562 the great auto-da-fé in the town square of Mani in the Yucatan, an estimated 5,000 idols, including jeweled skulls of ancestors, were destroyed and countless books burnt. Landa wrote:

‘We found a great number of books in these letters, and since they contained nothing but superstitions and falsehoods of the devil we burned them all, which they took most grievously, and which gave them great pain.’

Tragically, in its religious fervor, the Church, fearing that the conquered peoples would revert to their own beliefs, destroyed almost all Mayan and Aztec written culture and literature in the form codices in the Aztec capital and in Landa's auto-da-fé, a wanton act of pure destruction.

All that remained of 3,000 years of Maya written culture was just four books, the rest had gone up in flames, destroyed by the furiously obsessed monk, sacrificed on his burning altar and his faith in the Christian god.

It wasn’t until three centuries later did explorers rediscover beneath the dense jungle large stone buildings covered with carvings and texts throwing new light on a rich but forgotten civilisation.

Unfortunately not one word of the texts carved in the ancient stones could be understood.

When Landa returned to Spain, to defend himself against accusations of usurping the powers of the bishop, whilst awaiting judgement, he wrote Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, in which he described the region, its geography, flora and fauna, the little he knew of its history, the Maya writing system and their calendar.

Landa was vindicated and returned to New Spain where he was appointed Bishop of the Yucatan in 1572.

According to ecclesiastical sources, in spite of Landa's efforts to eradicate the tradition, the Maya were still producing codices when the Spanish finally conquered them, long after the defeat of the Aztecs. If fact, written hieroglyphic texts flourished for generations in books made of bark and coated with polished white lime on which the Mayan scribes recorded their history.

In his book Landa detailed what he termed an alphabet, a phonetic version of the Maya language, using the Roman alphabet and Spanish phonetics along with written examples to demonstrate his hypothesis.

His book was lost until 1862 when an abridged copy was discovered in the archives of the Spanish Royal Academy. Many attempts were made to test his hypothesis, but it was not until 1947, when with the help of Landa’s work, Knorozov finally found the key to unlock the Maya hieroglyphs.

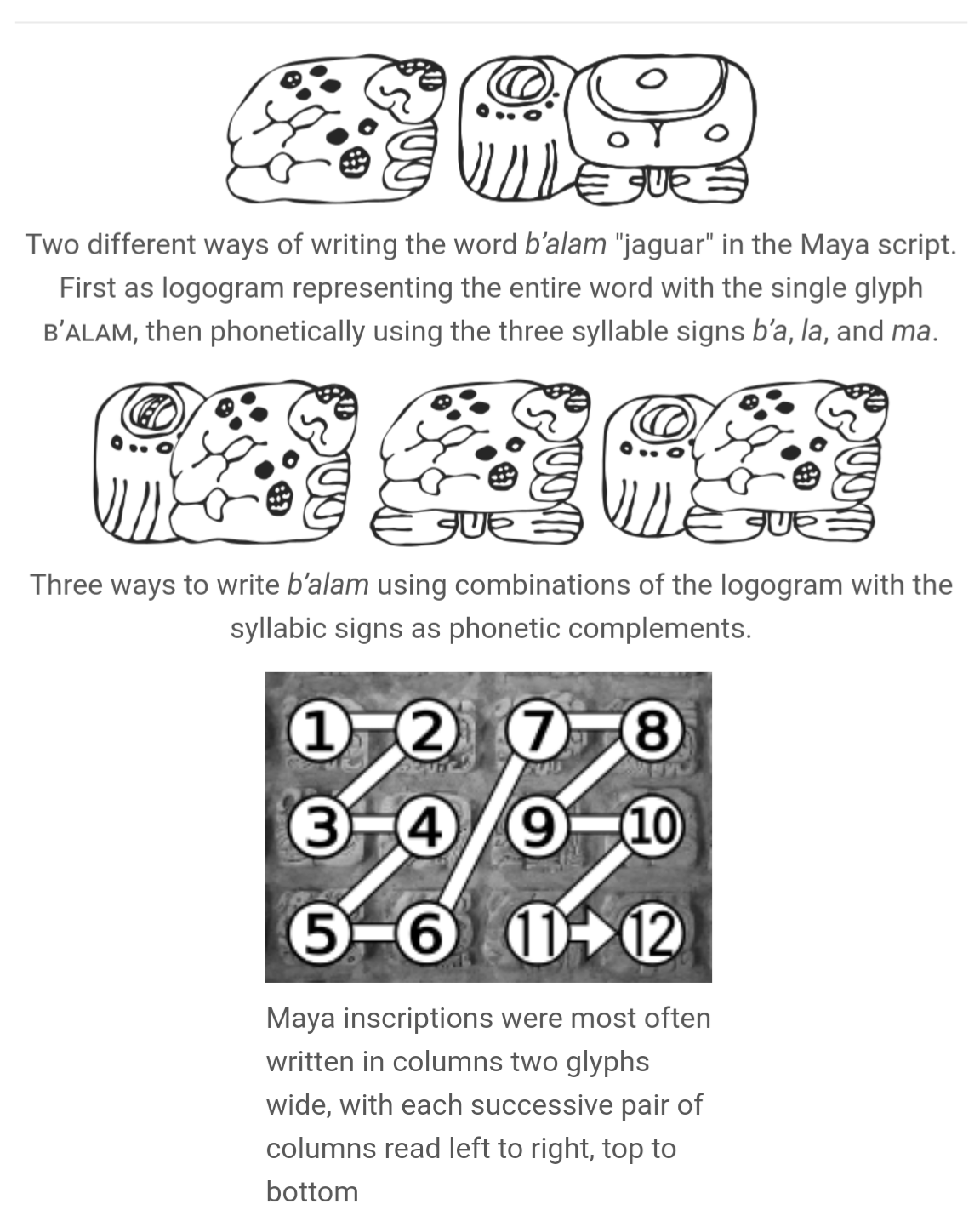

These were, however, very different from those employed in Egyptian and Sumerian scripts already known and deciphered by linguists, in that they were composed of ideographic elements and other phonetic symbols, without an alphabet. These logograms were complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs.

The 18th and 19th century archaeologists who explored the Maya Lowlands mistakenly called the texts carved on the stone facades of temples and stela hieroglyphics, for the simple reason they were similar in their minds to Egyptian hieroglyphics, although the two systems were totally unrelated.

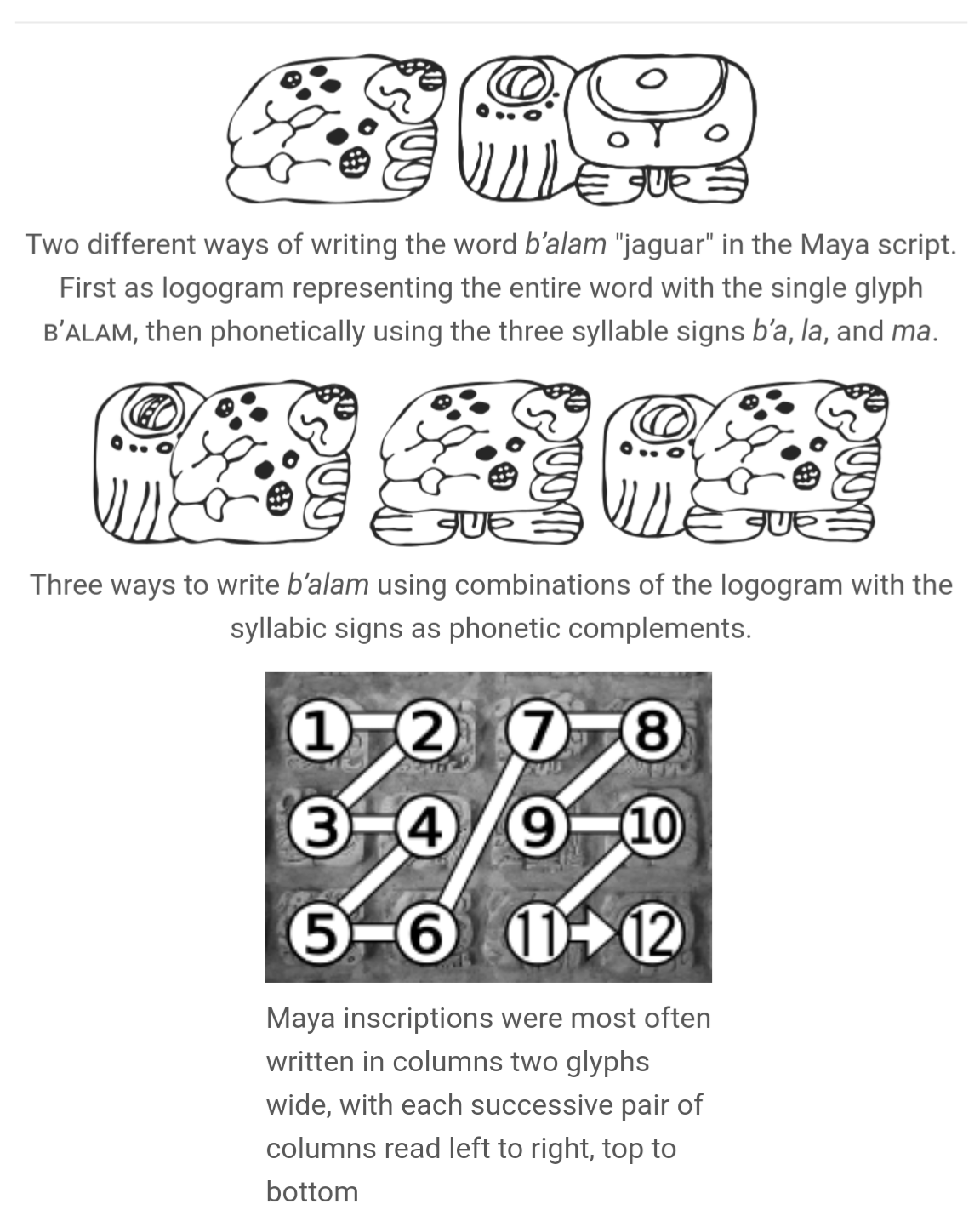

The Madrid Codex, the longest of the surviving codices, consisted of 56 pages written on both sides. Its texts, like those of the other codices, were written in the same logosyllabic script found throughout the Maya area dating from the 2nd to the 15th century AD.

Knorozov's analysis of Landa’s alphabet explained that the Maya hieroglyphs, which had at first appeared to be a form of pictographic writing, using animals, birds, men, gods, symbols and composite images, arranged into blocks to make a text, was not a pictographic system in which each image represented a specific word or idea, but in fact a syllabic system.

The Russian explained that Maya words were made up of consonant-vowel-consonant combinations, which enabled him to decipher a wide range of inscriptions until that moment incomprehensible.

During the 1960s, other Mayanists and researchers began to expand upon Knorozov’s ideas. Then in 1973, a major breakthrough came when the syllabic system enabled linguists to decipher a list of rulers of Palanque—a vast site in the south of Mexico where the Aztec and Maya civilisations met.