CHAPTER 10

DEMITRIEV WAS ONE OF ABOUT 20,000 Russians in Mexico, one twentieth of the number in the US. The relations between Mexico and Moscow were good, but nevertheless superficial, since the commercial exchanges between the two countries could be summed up by the fact that the value of goods exchanged between them was no more than that which crossed the US-Mexican border every 31 hours.

The event would mark forever the history of Mexican Russian relations was the assassination of the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky in Mexico City in 1940.

Those facts were not on Demitriev’s agenda when he returned to Mexico City from California. His first priority was to speak with the cultural attaché at the embassy, Nikita Gulyayev, who was a specialist in pre-Columbian history, he hoped she could tell him more about the codices and explain what they had to do with plants, in anything.

The first thing he learnt was that only 15 codices of the pre-contact period were known to exist today. Certain of which were in a multiple page Z-fold format, as opposed to modern books bound with a single spine on one side.

Nikita informed him they were of inestimable value, priceless. Which begged the question as to whether or not Simmonds had one of these and if so where did it come from, had it something to do with Wallace, perhaps there other treasures that Wallace had hidden, and where?

Nikita spoke Spanish and Nahuatl, she had studied Mexican and Central American history at Moscow State University's Faculty of History. She told him that a codex, which often conjured up a near mystical meaning, was nothing more than another word for a book. Pre-Hispanic codices were written in the form of painted images, glyphs not words. Glyphs were graphic symbols which the Spanish monks transliterated in a romanised version of Nahuatl, subsequently translated into Spanish and Latin.

In the codeces certain pictures represented the spoken word—logograms, whilst others showed ideas—pictograms and ideograms.

‘So how does this ideographic system function?’ Demitriev asked

‘Well, abstract concepts are represented by images, such as death for example which is represented by a body wrapped for burial, or war by a shield and a club.’

She picked up a book, Portraying The Aztec Past, opened it and stopped at a page showing the image of a codex. ‘This is the story of the codices Boturini, Azcatitlan, and Aubin. It was published by the University of Texas. Here, you can see the little scrolls coming from mouth of the person, that's speech,’ she said pointing at a symbol.

‘I see.’

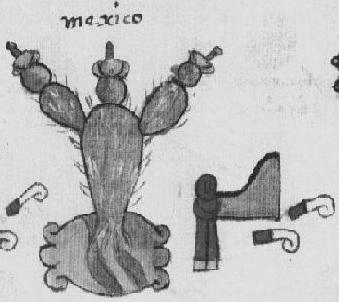

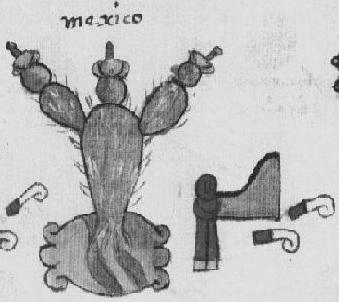

‘Then glyphs can be used as rebuses for different words with similar sounds. For example, the glyph for Tenochtitlan is represented by combining two pictograms a stone—te-tl, and a cactus—nochtli.

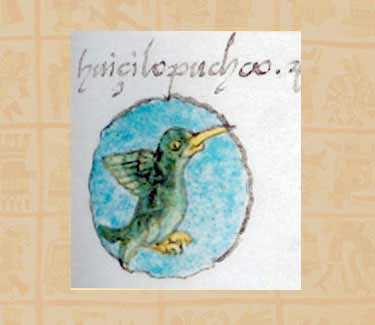

‘Another toponym, Huitzilopochco, an Aztec city-state, is symbolised by the picture of a hummingbird on a blue background. Blue was synonymous of the sun and by extrapolation the sun god Huitzilopochtli, whose name was Hummingbird’s South, here south means the left side of the world.’

‘Hmm ... looks like Chinese to me,' said Demitriev, trying to restrain his impatience as Nikita’s explanations flew over his head.

She nodded. ‘In a certain sense you could say there are similarities, though strictly speaking there is no relationship whatsoever with Chinese.’

‘Maya and Aztec are the same?’

‘No, compared to Maya hieroglyphs, Aztec glyphs do not have a defined reading order, they can be read in any direction, forming sounds, followed by a marker before the next word.’

‘What I’d like to know is what their codices have to do with plants?’

Nikita was surprised by his questions. Demitriev was not reputed as being the most intellectually cultivated members of the embassy's staff, those GRU agents parading as commercial attachés and the like were reputed for frequenting low life and thugs, after all their role was sowing chaos wherever and whenever the Kremlin deemed necessary.

Nikita was nevertheless interested in Demitriev's motivations, he was obviously hiding something. She decided to go along with him, to learn more, starting with the Libellus.

She commenced with Aztec ethnobotanically records that described food plants such as amaranth, avocado, beans, black cherry, cacao, chia, chili, chirimoya, cuajilote, guaje, huazontle, Spanish bayonet, maguey, maize, mamey, squash, sweet potato, tuna fruit as well as medicinal and stimulating herbs including thistle, lobelia, tobacco.

Then there was the agave, sacred to the Aztecs, known for its life-sustaining liquid, agua miel and its fermented product pulque, drunk by priests and sacrificial victims. The agave was used in more modern times for the production of tequila.

Plants such as Agave, Laelia, Yucca as well as Amaranthus , Capsicum, Leucaena, and Phaseolus were all part of the Mesoamerican agricultural tradition.

Even though much of Nikita’s explanation escaped him, Demitriev listened carefully, he was trained for that, seeking precious clues that would lead him to his enemies.

Nikita continued described the Viceroyalty Period, during which the Spanish Crown undertook scientific expeditions and surveys in the territories of New Spain. These were called Relaciones Geográficas and were kept in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville and the Real Academia de la Historia in Madrid.

‘They are still there today?’

‘Yes, very much so, they contain references to many trees and plants and their nutritional as well as medicinal properties.’

*

Until the unexpected discovery of the Wallace Codex, the Badianus Manuscript had been the first known illustrated text of traditional Nahua medicine and plants. The herbal had been compiled under Jacobo de Grado, head of the Convent of Tlatelolco and the College of Santa Cruz, and translated for Don Francisco de Mendoza, son of Don Antonio de Mendoza, the viceroy of New Spain. Mendoza sent the Latin manuscript to Spain, where it was deposited in the royal library. There it presumably remained until it came into the possession of Diego de Cortavila y Sanabria, pharmacist to King Philip IV. Later it appeared in the library of the Italian Cardinal Francesco Barberini, where it remained remained until the library became part of the Vatican Library. Now, four centuries after leaving Mexico, the Libellus is kept in the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Mexico City, returned to its home by Pope John Paul II.

‘The Badinus manuscript only deals with the medical conditions and curative aspects of the plants, for various ailments,’ Nikita said slyly quoting the text, ‘including, stupidity of the mind, goaty armpits of sick people, lassitude, and medicine to take away foul and fetid breath.’

Demitriev wrinkled his nose, ignoring any insinuation.

‘Another codex is the Historia natural de la Nueva España compiled by Francisco Hernández de Toledo, the physician of Phillip II of Spain,’ Nikita continued. ‘Hernández participated in the expedition that took place between 1571 and 1576, during which he collected data on more than 3,000 plant species and amongst 500 animals, including 230 species of birds.’

‘It was the most important compendium of Nahuatl plants and their medicinal properties and other uses practiced by the Mexicans.’

‘Unfortunately,’ she regretted, ‘the original manuscript was lost in the 17th century when the library of the Escorial Castle, the royal palace near Madrid, burnt down, and much of invaluable treasures went up in smoke.’

‘It seems the Aztecs were not as primitive as the Spanish described them,’ Demitriev grudgingly admitted.

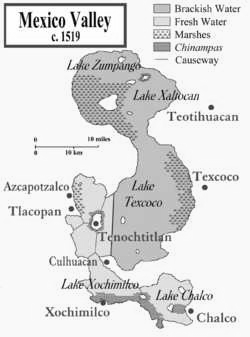

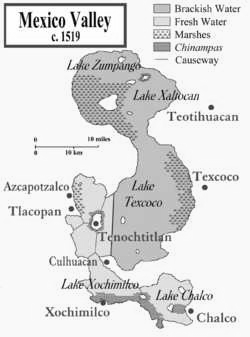

‘Strictly speaking the Aztecs, as we call them were not alone, but it was they who dominated the empire and its many ethnic groups that lived around Tenochtitlan and Lake Texcoco, these included the Mexica, Culhua, Acolhua, Tepaneca, Matlazinca, to name a few.’

‘They were in reality a mixed group, all of whom traced their ancestry to a place called Aztlan, from where we got the word Aztec.’

‘Where was Aztlan?’

‘We’re not very sure where Aztlan was, but most evidence puts it in the southwest US from where the Aztecs migrated south into Mexico over the centuries.’

‘I see,’ he said thinking of Southern California and its adjoining regions.

‘They all spoke, and still speak Nahuatl and its various dialects. Like English today or French or Latin in the past, Nahuatl spread into many other cultural and ethnic areas. By the time the Spaniards came, even the Maya spoke Nahuatl in addition to their own languages.

‘We use a lot of those words today in Russian or English, words like chocolate, tomato, avocado, chilli, coyote, ocelot, atlatl-that’s a throwing stick, guacamole, or from the Mayan- cacao, shark, cigar.

‘I still don't get all this story about plants.’

‘Well, it started when Philip II of Spain sent Francisco Hernandez, one of his physicians, on the scientific mission to New Spain, Hernandez was instructed to investigate its medicinal plants and their use, how and where they grew, and their effectiveness.’

‘He arrived in Mexico in 1570 and stayed seven years. It was a huge task. Hernandez interrogated native physicians and did his own evaluations according to the Galenical theory current in Europe at the time.’

‘Galenical?’

‘Galen of Pergamon was a Roman physician, surgeon and philosopher. He expanded Hippocrates’ medical theory of the human body, which he believed was made up of four humors—blood, phlegm, black and yellow bile.’

Demitriev had never heard of Galen or his humors, but the name Galen said something to him ... Galenical, Galenus, Galenium. He wracked his brain, hadn’t he overheard it at the Getty Center, at the bar?

Ageing and longevity have been central to the concerns of Western natural philosophy since the time of Hippocrates, developed by Galen, in his theory of ageing and health in old age.

‘So this Hernandez was interested in medicinal plants.’

‘You could say that.’

Demitriev recalled medicinal plants had been an important subject of the conference at the Getty Center in Santa Monica.

‘The original version of his book,’ Nikita told him, ‘was a huge work describing Aztec medicinal plants, minerals, and animals, with its irreplaceable illustrations, which was destroyed in the fire in 1671. What we now have is an incomplete copy made in 1648.’

She recalled how Hernandez had marveled at the huge number of herbs unknown to the Spanish in the New World, some with known uses and others without, almost all of which were named and described by Aztec herbalists.

He wrote: ‘Although, as in many other medical systems, including our own, illnesses were treated by imploring the gods and using magical remedies, the Aztecs also had knowledge based on research and experience. The Aztecs had considerable empirical knowledge about plants. The emperor Moctezuma I established the first botanical garden in the 15th Century and as the Mexica conquered new lands, specimens were brought to these and other botanical gardens. Natives of newly conquered areas were also brought to tend plants from their areas. Among other things these gardens were used for medical research; plants were given away to patients with the condition that they report on the results.’

Demitriev concluded he would have to get closer to Anna Basurko and her friends to learn their secrets, which he was now certain existed.