CHAPTER IX

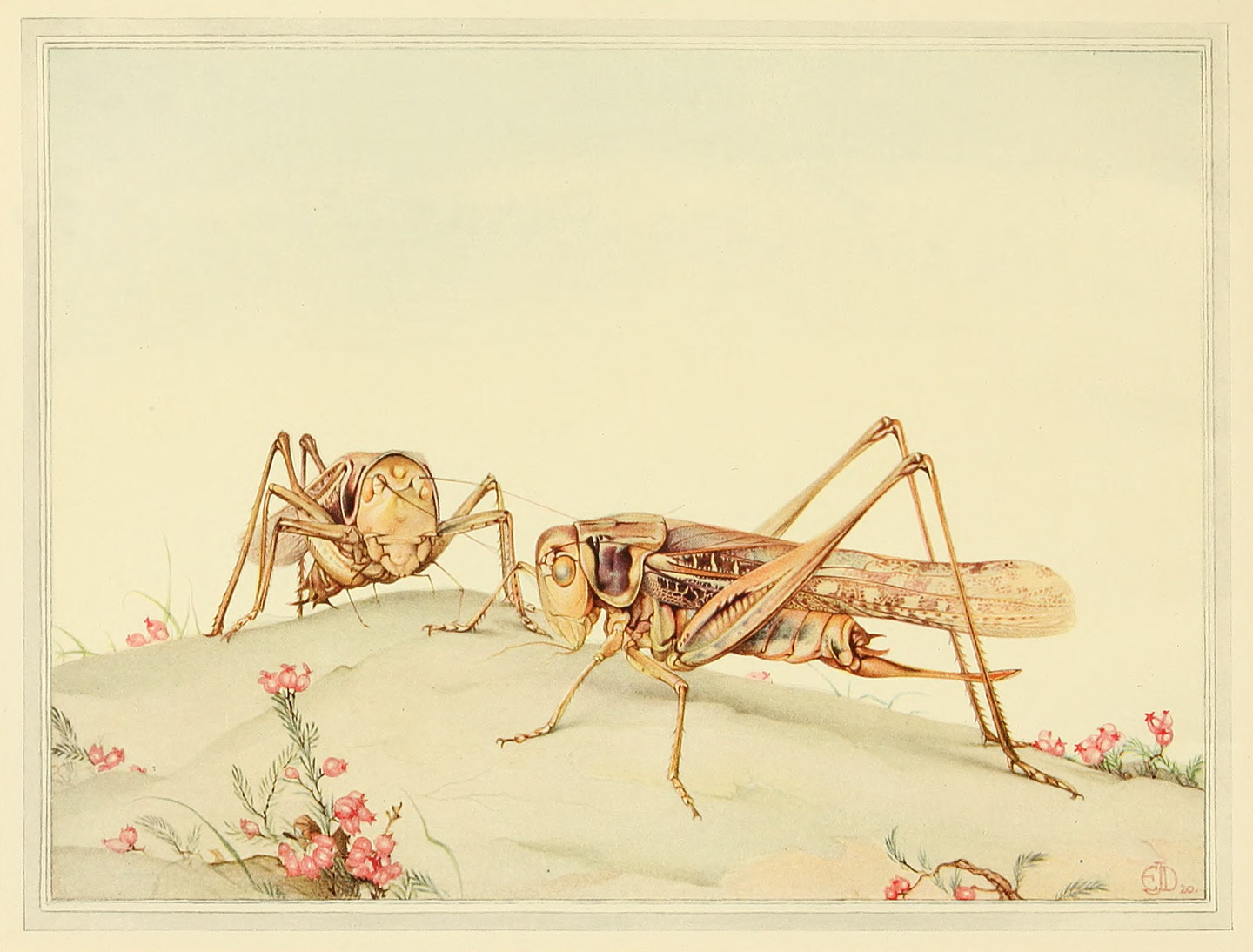

TWO STRANGE GRASSHOPPERS

I

THE EMPUSA

The sea, where life first appeared, still preserves in its depths many of those curious shapes which were the earliest specimens of the animal kingdom. But the land has almost entirely lost the strange forms of other days. The few that remain are mostly insects. One of these is the Praying Mantis, whose remarkable shape and habits I have already described to you. Another is the Empusa.

This insect, in its undeveloped or larval state, is certainly the strangest creature in all Provence: a slim, swaying thing of so fantastic an appearance that unaccustomed fingers dare not lay hold of it. The children of my neighbourhood are so much impressed by its startling shape that they call it “the Devilkin.” They imagine it to be in some way connected with witchcraft. One comes across it, though never in great numbers, in the spring up to May; in autumn; and sometimes in winter if the sun be strong. The tough grasses of the waste-lands, the stunted bushes which catch the sunshine and are sheltered from the wind by a few heaps of stones, are the chilly Empusa’s favourite dwelling.

I will tell you, as well as I can, what she looks like. The tail-end of her body is always twisted and curved up over her back so as to form a crook, and the lower surface of her body (that is to say, of course, the upper surface of the crook) is covered with pointed, leaf-shaped scales, arranged in three rows. The crook is propped on four long, thin legs, like stilts; and on each of these legs, at the point where the thigh joins the shin, is a curved, projecting blade not unlike that of a cleaver.

In front of this crook on stilts, this four-legged stool, there rises suddenly—very long and almost perpendicular—the stiff corselet or bust. It is round and slender as a straw, and at the end of it is the hunting-trap, copied from that of the Mantis. This consists of a harpoon sharper than a needle, and a cruel vice with jaws toothed like a saw. The jaw, or blade formed by the upper arm, is hollowed into a groove and carries five long spikes on each side, with smaller indentations in between. The jaw formed by the fore-arm is grooved in the same way, but the teeth are finer, closer, and more regular. When at rest, the saw of the fore-arm fits into the groove of the upper arm. If the machine were only larger it would be a fearful instrument of torture.

The head is in keeping with this arsenal. What a queer head it is! A pointed face, with curled moustaches; large goggle eyes; between them the blade of a dirk; and on the forehead a mad, unheard-of thing—a sort of tall mitre, an extravagant head-dress that juts forward, spreading right and left into peaked wings. What does the Devilkin want with that monstrous pointed cap, as magnificent as any ever worn by astrologer of old? The use of it will appear presently.

The creature’s colouring at this time is commonplace—chiefly grey. As it develops it becomes faintly striped with pale green, white, and pink.

If you come across this fantastic object in the bramble-bushes, it sways upon its four stilts, it wags its head at you knowingly, it twists its mitre round and peers over its shoulder. You seem to see mischief in its pointed face. But if you try to take hold of it this threatening attitude disappears at once; the raised corselet is lowered, and the creature makes off with mighty strides, helping itself along with its weapons, with which it clutches the twigs. If you have a practiced eye, however, the Empusa is easily caught, and penned in a cage of wire-gauze.

At first I was uncertain how to feed them. My Devilkins were very little, a month or two old at most. I gave them Locusts suited to their size, the smallest I could find. They not only refused them, but were afraid of them. Any thoughtless Locust that meekly approached an Empusa met with a bad reception. The pointed mitre was lowered, and an angry thrust sent the Locust rolling. The wizard’s cap, then, is a defensive weapon. As the Ram charges with his forehead, so the Empusa butts with her mitre.

I next offered her a live House-fly, and this time the dinner was accepted at once. The moment the Fly came within reach the watchful Devilkin turned her head, bent her corselet slantwise, harpooned the Fly, and gripped it between her two saws. No Cat could pounce more quickly on a Mouse.

To my surprise I found that the Fly was not only enough for a meal, but enough for the whole day, and often for several days. These fierce-looking insects are extremely abstemious. I was expecting them to be ogres, and found them with the delicate appetites of invalids. After a time even a Midge failed to tempt them, and through the winter months they fasted altogether. When the spring came, however, they were ready to indulge in a small piece of Cabbage Butterfly or Locust; attacking their prey invariably in the neck, like the Mantis.

The young Empusa has one very curious habit when in captivity. In its cage of wire-gauze its attitude is the same from first to last, and a most strange attitude it is. It grips the wire by the claws of its four hind-legs, and hangs motionless, back downwards, with the whole of its body suspended from those four points. If it wishes to move, its harpoons open in front, stretch out, grasp a mesh of the wire, and pull. This process naturally draws the insect along the wire, still upside down. Then the jaws close back against the chest.

And this upside-down position, which seems to us so trying, lasts for no short while. It continues, in my cages, for ten months without a break. The Fly on the ceiling, it is true, adopts the same position; but she has her moments of rest. She flies, she walks in the usual way, she spreads herself flat in the sun. The Empusa, on the other hand, remains in her curious attitude for ten months on end, without a pause. Hanging from the wire netting, back downwards, she hunts, eats, digests, dozes, gets through all the experiences of an insect’s life, and finally dies. She clambers up while she is still quite young; she falls down in her old age, a corpse.

This custom is all the more remarkable in that it is practised only in captivity. It is not an instinctive habit of the race; for out of doors the insect, except at rare intervals, stands on the bushes back upwards.

Strange as the performance is, I know of a similar case that is even more peculiar: the attitude of certain Wasps and Bees during the night’s rest. A particular Wasp, an Ammophila with red fore-legs, is plentiful in my enclosure towards the end of August, and likes to sleep in one of the lavender borders. At dusk, especially after a stifling day when a storm is brewing, I am sure to find the strange sleeper settled there. Never was a more eccentric attitude chosen for a night’s rest. The jaws bite right into the lavender-stem. Its square shape supplies a firmer hold than a round stalk would give. With this one and only prop the Wasp’s body juts out stiffly at full length, with legs folded. It forms a right angle with the stalk, so that the whole weight of the insect rests upon the mandibles.

The Ammophila is enabled by its mighty jaws to sleep in this way, extended in space. It takes an animal to think of a thing like that, which upsets all our previous ideas of rest. Should the threatening storm burst and the stalk sway in the wind, the sleeper is not troubled by her swinging hammock; at most, she presses her fore-legs for a moment against the tossing stem. Perhaps the Wasp’s jaws, like the Bird’s toes, possess the power of gripping more tightly in proportion to the violence of the wind. However that may be, there are several kinds of Wasps and Bees who adopt this strange position,—gripping a stalk with their mandibles, and sleeping with their bodies outstretched and their legs folded back. This state of things makes us wonder what it is that really constitutes rest.

About the middle of May the Empusa is transformed into her full-grown condition. She is even more remarkable in figure and attire than the Praying Mantis. She still keeps some of her youthful eccentricities—the bust, the weapons on her knees, and the three rows of scales on the lower surface of her body. But she is now no longer twisted into a crook, and is comelier to look upon. Large pale-green wings, pink at the shoulder and swift in flight, cover the white and green stripes that ornament the body below. The male Empusa, who is a dandy, adorns himself, like some of the Moths, with feathery antennæ.

When, in the spring, the peasant meets the Empusa, he thinks he sees the common Praying Mantis, who is a daughter of the autumn. They are so much alike that one would expect them to have the same habits. In fact, any one might be tempted, led away by the extraordinary armour, to suspect the Empusa of a mode of life even more atrocious than that of the Mantis. This would be a mistake: for all their war-like aspect the Empusæ are peaceful creatures.

Imprisoned in their wire-gauze bell-jar, either in groups of half a dozen or in separate couples, they at no time lose their placidity. Even in their full-grown state they are very small eaters, and content themselves with a fly or two as their daily ration.

Big eaters are naturally quarrelsome. The Mantis, gorged with Locusts, soon becomes irritated and shows fight. The Empusa, with her frugal meals, is a lover of peace. She indulges in no quarrels with her neighbours, nor does she pretend to be a ghost, with a view to frightening them, after the manner of the Mantis. She never unfurls her wings suddenly nor puffs like a startled Adder. She has never the least inclination for the cannibal banquets at which a sister, after being worsted in a fight, is eaten up. Nor does she, like the Mantis, devour her husband. Such atrocities are here unknown.

The organs of the two insects are the same. These profound moral differences, therefore, are not due to any difference in the bodily form. Possibly they may arise from the difference in food. Simple living, as a matter of fact, softens character, in animals as in men; over-feeding brutalises it. The glutton, gorged with meat and strong drink—a very common cause of savage outbursts—could never be as gentle as the self-denying hermit who lives on bread dipped into a cup of milk. The Mantis is a glutton: the Empusa lives the simple life.

And yet, even when this is granted, one is forced to ask a further question. Why, when the two insects are almost exactly the same in form, and might be expected to have the same needs, should the one have an enormous appetite and the other such temperate ways? They tell us, in their own fashion, what many insects have told us already: that inclinations and habits do not depend entirely upon anatomy. High above the laws that govern matter rise other laws that govern instincts.

II

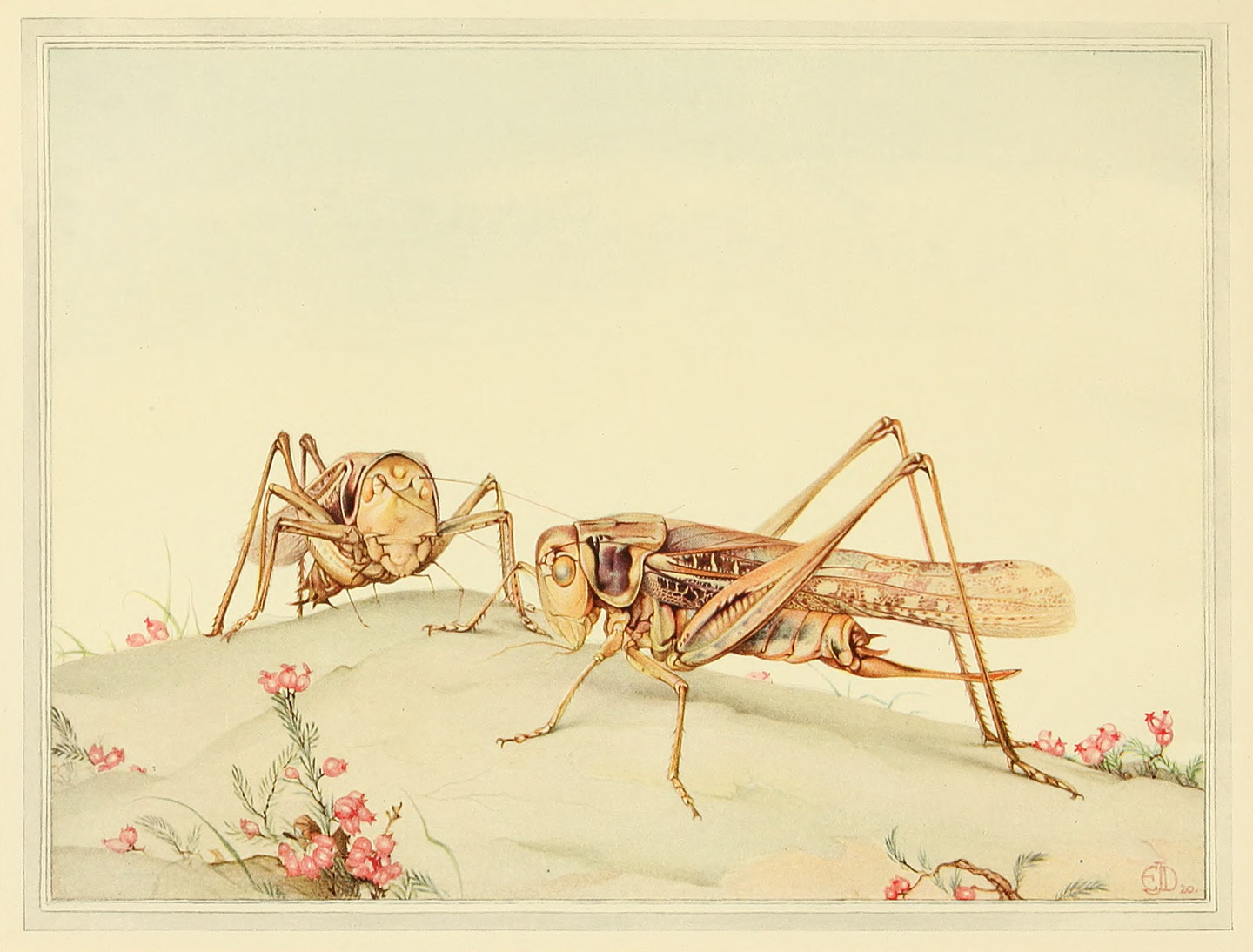

THE WHITE-FACED DECTICUS

The White-faced Decticus stands at the head of the Grasshopper clan in my district, both as a singer and as an insect of imposing presence. He has a grey body, a pair of powerful mandibles, and a broad ivory face. Without being plentiful, he is neither difficult nor wearisome to hunt. In the height of summer we find him hopping in the long grass, especially at the foot of the sunny rocks where the turpentine-tree takes root.

The Greek word dectikos means biting, fond of biting. The Decticus is well named. It is eminently an insect given to biting. Mind your finger if this sturdy Grasshopper gets hold of it: he will rip it till the blood comes. His powerful jaw, of which I have to beware when I handle him, and the large muscles that swell out his cheeks, are evidently intended for cutting up leathery prey.

THE WHITE-FACED DECTICUS

The Greek word dectikos means biting, fond of biting. The Decticus is well named. It is eminently an insect given to biting

I find, when the Decticus is imprisoned in my menagerie, that any fresh meat tasting of Locust or Grasshopper suits his needs. The blue-winged Locust is the most frequent victim. As soon as the food is introduced into the cage there is an uproar, especially if the Dectici are hungry. They stamp about, and dart forward clumsily, being hampered by their long shanks. Some of the Locusts are caught at once, but others with desperate bounds rush to the top of the cage, and there hang on out of the reach of the Grasshopper, who is too stout to climb so high. But they have only postponed their fate. Either because they are tired, or because they are tempted by the green stuff below, they will come down, and the Dectici will be after them immediately.

This Grasshopper, though his intellect is dull, possesses the art of scientific killing of which we have seen instances elsewhere. He always spears his prey in the neck, and, to make it helpless as quickly as possible, begins by biting the nerves that enable it to move. It is a very wise method, for the Locust is hard to kill. Even when beheaded he goes on hopping. I have seen some who, though half-eaten, kicked out so desperately that they succeeded in escaping.

With his weakness for Locusts, and also for certain seeds that are harmful to unripe corn, these Grasshoppers might be of some service to agriculture if only there were more of them. But nowadays his assistance in preserving the fruits of the earth is very feeble. His chief interest in our eyes is the fact that he is a memorial of the remotest times. He gives us a vague glimpse of habits now out of use.

It was thanks to the Decticus that I first learnt one or two things about young Grasshoppers.

Instead of packing their eggs in casks of hardened foam, like the Locust and the Mantis, or laying them in a twig like the Cicada, Grasshoppers plant them like seeds in the earth.

The mother Decticus has a tool at the end of her body with which she scrapes out a little hole in the soil. In this hole she lays a certain number of eggs, then loosens the dust round the side of the hole and rams it down with her tool, very much as we should pack the earth in a hole with a stick. In this way she covers up the well, and then sweeps and smooths the ground above it.

She then goes for a little walk in the neighbourhood, by way of recreation. Soon she comes back to the place where she has already laid her eggs, and, very near the original spot, which she recognises quite well, begins the work afresh. If I watch her for an hour I see her go through this whole performance, including the short stroll in the neighbourhood, no less than five times. The points where she lays the eggs are always very close together.

When everything is finished I examine the little pits. The eggs lie singly, without any cell or sheath to protect them. There are about sixty of them altogether, pale lilac-grey in colour, and shaped like a shuttle.

When I began to observe the ways of the Decticus I was anxious to watch the hatching, so at the end of August I gathered plenty of eggs, and placed them in a small glass jar with a layer of sand. Without suffering any apparent change they spent eight months there under cover, sheltered from the frosts, the showers, and the overpowering heat of the sun, which they would be obliged to endure out of doors.

When June came, the eggs in my jar showed no sign of being about to hatch. They were just as I had gathered them nine months before, neither wrinkled nor tarnished, but on the contrary wearing a most healthy look. Yet in June young Dectici are often to be met in the fields, and sometimes even those of larger growth. What was the reason of this delay, I wondered.

Then an idea came to me. The eggs of the Grasshopper are planted like seeds in the earth, where they are exposed, without any protection, to snow and rain. Those in my jar had spent two-thirds of the year in a state of comparative dryness. Since they were sown like seeds, perhaps they needed, to make them hatch, the moisture that seeds require to make them sprout. I resolved to try.

I placed at the bottom of some glass tubes a pinch of backward eggs taken from my collection, and on the top I heaped lightly a layer of fine, damp sand. I closed the tubes with plugs of wet cotton, to keep the air in them constantly moist. Any one seeing my preparations would have supposed me to be a botanist experimenting with seeds.

My hopes were fulfilled. In the warmth and moisture the eggs soon showed signs of hatching. They began to swell, and the bursting of the shell was evidently close at hand. I spent a fortnight in keeping a tedious watch at every hour of the day, for I had to surprise the young Decticus actually leaving the egg, in order to solve a question that had long been in my mind.

The question was this. The Grasshopper is buried, as a rule, about an inch below the surface of the soil. Now the new-born Decticus, hopping awkwardly in the grass at the approach of summer, has, like the full-grown insect, a pair of very long tentacles, as slender as hairs; while he carries behind him two extraordinary legs, two enormous hinged jumping-poles that would be very inconvenient for ordinary walking. I wished to find out how the feeble little creature set to work, with this cumbrous luggage, to make its way to the surface of the earth. By what means could it clear a passage through the rough soil? With its feathery antennæ, which an atom of sand can break, and its immense shanks, which are disjointed by the least effort, this mite is plainly incapable of freeing itself.

As I have already told you, the Cicada and the Praying Mantis, when issuing, the one from his twig, and the other from his nest, wear a protective covering like an overall. It seemed to me that the little Grasshopper, too, must come out through the sand in a simpler, more compact form than he wears when he hops about the lawn on the day after his birth.

Nor was I mistaken. The Decticus, like the others, wears an overall for the occasion. The tiny, flesh-white creature is cased in a scabbard which keeps the six legs flattened against the body, stretching backwards, inert. In order to slip more easily through the soil his shanks are tied up beside him; while the antennæ, those other inconvenient appendages, are pressed motionless against the parcel.

The head is very much bent against the chest. With the big black specks that are going to be its eyes, and its inexpressive, rather swollen mask, it suggests a diver’s helmet. The neck opens wide at the back, and, with a slow throbbing, by turns swells and sinks. It is by means of this throbbing protrusion through the opening at the back of the head that the new-born insect moves. When the lump is flat, the head pushes back the damp sand a little way and slips into it by digging a tiny pit. Then the swelling is blown out and becomes a knob which sticks firmly in the hole. This supplies the resistance necessary for the grub to draw up its back and push. Thus a step forward is made. Each thrust of the motor-blister helps the little Decticus upon the upward path.

It is pitiful to see this tender creature, still almost colourless, knocking with its swollen neck and ramming the rough soil. With flesh that is not yet hardened it is painfully fighting stone; and fighting it so successfully that in the space of a morning it makes a gallery, either straight or winding, an inch long and as wide as an average straw. In this way the harassed insect reaches the surface.

Before it is altogether freed from the soil the struggler halts for a moment, to recover from the effects of the journey. Then, with renewed strength, it makes a last effort: it swells the protrusion at the back of its head as far as it will go, and bursts the sheath that has protected it so far. The creature throws off its overall.

Here, then, is the Decticus in his youthful shape, quite pale still, but darker the next day, and a regular blackamoor compared with the full-grown insect. As a prelude to the ivory face of his riper age he wears a narrow white stripe under his hinder thighs.

Little Decticus, hatched before my eyes, life opens for you very harshly! Many of your relatives must die of exhaustion before winning their freedom. In my tubes I see numbers who, being stopped by a grain of sand, give up the struggle half-way and become furred with a sort of silky fluff. Mildew soon absorbs their poor little remains. And when carried out without my help, their journey to the surface must be even more dangerous, for the soil out of doors is coarse and baked by the sun.

The little white-striped nigger nibbles at the lettuce-leaf I give him, and leaps about gaily in the cage where I have housed him. I could easily rear him, but he would not teach me much more. So I restore him to liberty. In return for what he has taught me I give him the grass and the Locusts in the garden.

For he taught me that Grasshoppers, in order to leave the ground where the eggs are laid, wear a temporary form which keeps those too cumbrous parts, the long legs and antennæ, swathed together in a sheath. He taught me, too, that this mummy-like creature, fit only to lengthen and shorten itself a little, has for its means of travelling a hernia in the neck, a throbbing blister—an original piece of mechanism which, when I first observed the Decticus, I had never seen used as an aid to progression.