CHAPTER X

COMMON WASPS

I

THEIR CLEVERNESS AND STUPIDITY

Wishing to observe a Wasp’s nest I go out, one day in September, with my little son Paul, who helps me with his good sight and his undivided attention. We look with interest at the edges of the footpaths.

Suddenly Paul cries: “A Wasp’s nest! A Wasp’s nest, as sure as anything!” For, twenty yards away, he has seen rising from the ground, shooting up and flying away, now one and then another swiftly moving object, as though some tiny crater in the grass were hurling them forth.

We approach the spot with caution, fearing to attract the attention of the fierce creatures. At the entrance-door of their dwelling, a round opening large enough to admit a man’s thumb, the inmates come and go, busily passing one another as they fly in opposite directions. Burr! A shudder runs through me at the thought of the unpleasant time we should have, did we incite these irritable warriors to attack us by inspecting them too closely. Without further investigation, which might cost us too dear, we mark the spot, and resolve to return at nightfall. By that time all the inhabitants of the nest will have come home from the fields.

The conquest of a nest of Common Wasps would be rather a serious undertaking if one did not act with a certain amount of prudence. Half a pint of petrol, a reed-stump nine inches long, and a good-sized lump of clay or loam, kneaded to the right consistency—such are my weapons, which I have come to consider the best and simplest, after various trials with less successful means.

The suffocating method is necessary, unless I use costly measures which I cannot afford. When Réaumur wanted to place a live Wasp’s nest in a glass case with a view to observing the habits of the inmates, he employed helpers who were used to the painful job, and were willing, for a handsome reward, to serve the man of science at the cost of their skins. But I, who should have to pay with my own skin, think twice before digging up the nest I desire. I begin by suffocating the inhabitants. Dead Wasps do not sting. It is a brutal method, but perfectly safe.

I use petrol because its effects are not too violent, and in order to make my observations I wish to leave a small number of survivors. The question is how to introduce it into the cavity containing the Wasp’s nest. A vestibule, or entrance-passage, about nine inches long, and very nearly horizontal, leads to the underground cells. To pour the petrol straight into the mouths of this tunnel would be a blunder that might have serious consequences later on. For so small a quantity of petrol would be absorbed by the soil and would never reach the nest; and next day, when we might think we were digging safely, we should find an infuriated swarm under the spade.

The bit of reed prevents this mishap. When inserted into the passage it forms a water-tight funnel, and carries the petrol to the cavern without the loss of a drop, and as quickly as possible. Then we fix the lump of kneaded clay into the entrance-hole, like a stopper. We have nothing to do now but wait.

When we are going to perform this operation Paul and I set out, carrying a lantern and a basket with the implements, at nine o’clock on some mild, moonlit evening. While the farmhouse Dogs are yelping at each other in the distance, and the Screech Owl is hooting in the olive-trees, and the Italian Crickets are performing their symphony in the bushes, Paul and I chat about insects. He asks questions, eager to learn, and I tell him the little that I know. So delightful are our nights of Wasp-hunting that we think little of the loss of sleep or the chance of being stung!

The pushing of the reed into the hole is the most delicate matter. Since the direction of the passage is unknown there is some hesitation, and sometimes sentries come flying out of the Wasp’s guard-house to attack the operator’s hand. To prevent this one of us keeps watch, and drives away the enemy with a handkerchief. And after all, a swelling on one’s hand, even if it does smart, is not much to pay for an idea.

As the petrol streams into the cavern we hear the threatening buzz of the population underground. Then quick!—the door must be closed with the wet clay, and the clod kicked once or twice with the heel to make the stopper solid. There is nothing more to be done for the present. Off we go to bed.

With a spade and a trowel we are back on the spot at dawn. It is wise to be early, because many Wasps will have been out all night, and will want to get into their home while we are digging. The chill of the morning will make them less fierce.

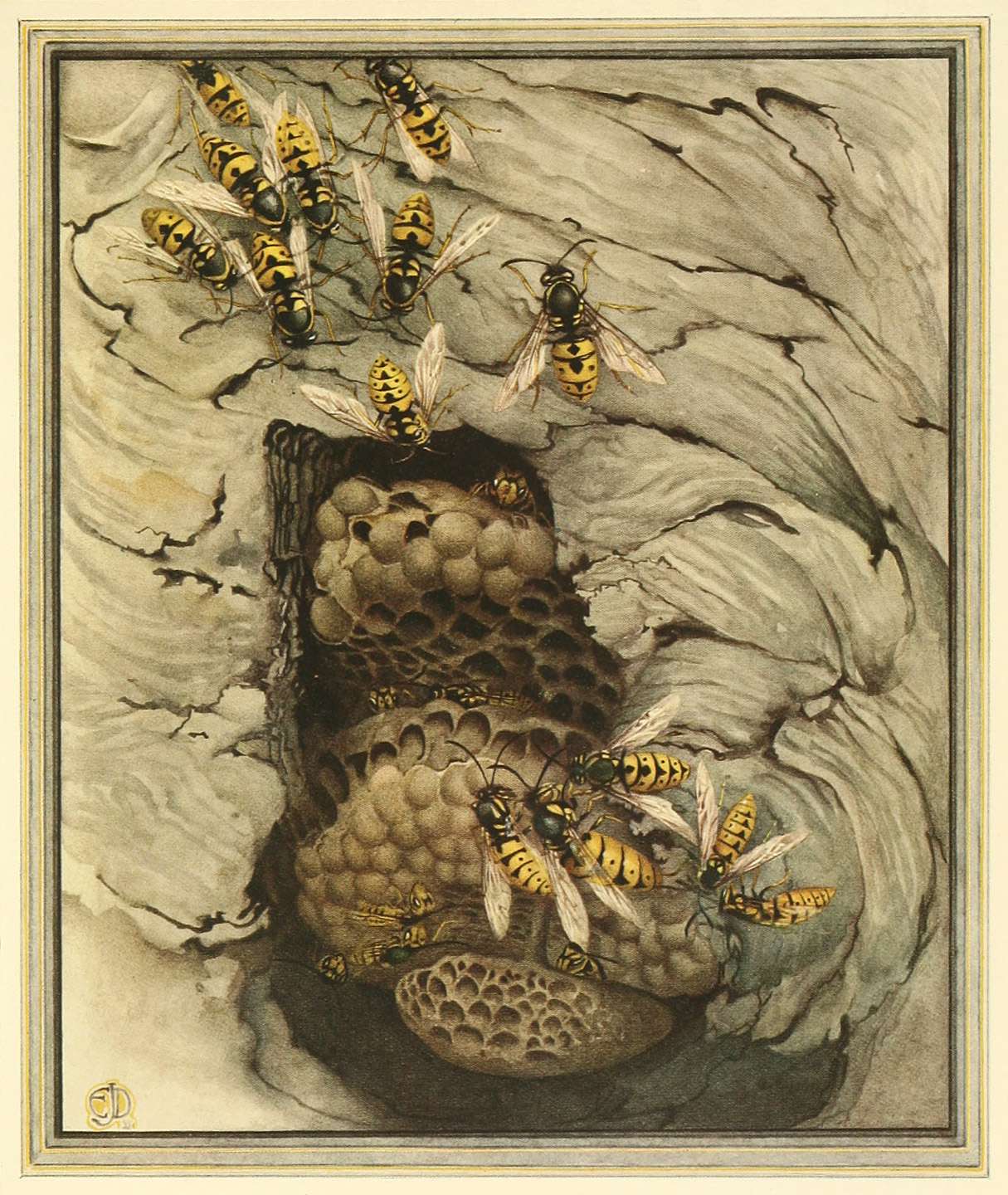

In front of the entrance-passage, in which the reed is still sticking, we dig a trench wide enough to allow us free movement. Then the side of this ditch is carefully cut away, slice after slice, until, at a depth of about twenty inches, the Wasp’s nest is revealed, uninjured, slung from the roof of a spacious cavity.

It is indeed a superb achievement, as large as a fair-sized pumpkin. It hangs free on every side except at the top, where various roots, mostly of couch-grass, penetrate the thickness of the wall and fasten the nest firmly. Its shape is round wherever the ground has been soft, and of the same consistency all through. In stony soil, where the Wasps meet with obstacles in their digging, the sphere becomes more or less misshapen.

A space of a hand’s-breadth is always left open between the paper nest and the sides of the underground vault. This space is the wide street along which the builders move unhindered at their continual task of enlarging and strengthening the nest, and the passage that leads to the outer world opens into it. Underneath the nest is a much larger unoccupied space, rounded into a big basin, so that the wrapper of the nest can be enlarged as fresh cells are added. This cavity also serves as a dust-bin for refuse.

The cavity was dug by the Wasps themselves. Of that there is no doubt; for holes so large and so regular do not exist ready-made. The original foundress of the nest may have seized on some cavity made by a Mole, to help her at the beginning; but the greater part of the enormous vault was the work of the Wasps. Yet there is not a scrap of rubbish outside the entrance. Where is the mass of earth that has been removed?

It has been spread over such a large surface of ground that it is unnoticed. Thousands and thousands of Wasps work at digging the cellar, and enlarging it as that becomes necessary. They fly up to the outer world, each carrying a particle of earth, which they drop on the ground at some distance from the nest, in all directions. Being scattered in this way the earth leaves no visible trace.

The Wasp’s nest is made of a thin, flexible material like brown paper, formed of particles of wood. It is streaked with bands, of which the colour varies according to the wood used. If it were made in a single continuous sheet it would give little protection against the cold. But the Common Wasp, like the ballon-maker, knows that heat may be preserved by means of a cushion of air contained by several wrappers. So she makes her paper-pulp into broad scales, which overlap loosely and are laid on in numerous layers. The whole forms a coarse blanket, thick and spongy in texture and well filled with stagnant air. The temperature under this shelter must be truly tropical in hot weather.

The fierce Hornet, chief of the Wasps, builds her nest on the same principle. In the hollow of a willow, or within some empty granary, she makes, out of fragments of wood, a very brittle kind of striped yellow cardboard. Her nest is wrapped round with many layers of this substance, laid on in the form of broad convex scales which are welded to one another. Between them are wide intervals in which air is held motionless.

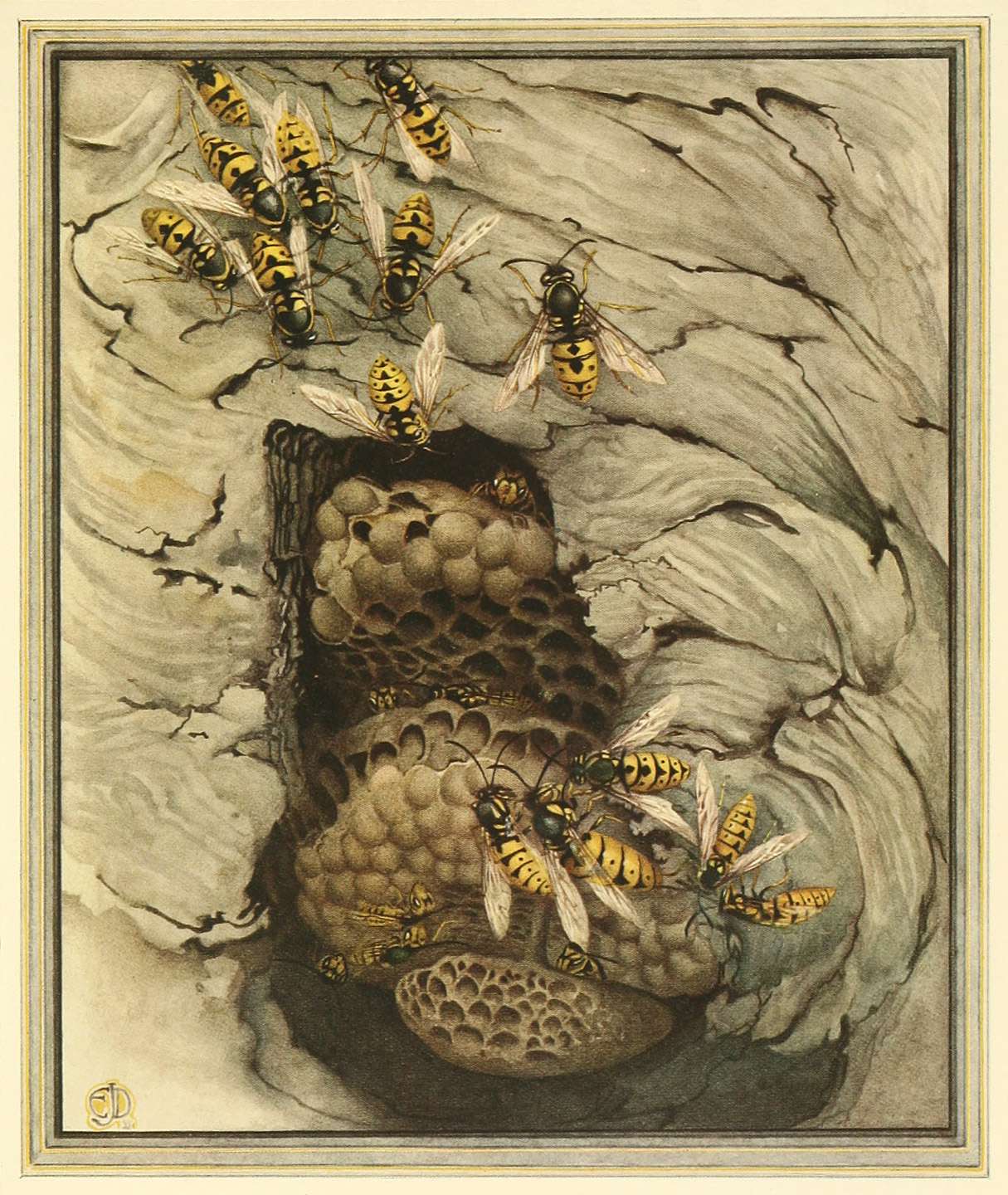

COMMON WASPS

The Wasp’s nest is made of a thin, flexible material like brown paper, formed of particles of wood

The Wasp, then, often acts in accordance with the laws of physics and geometry. She employs air, a non-conductor of heat, to keep her home warm; she made blankets before man thought of it; she builds the outer walls of the nest in the shape that gives her the largest amount of room in the smallest wrapper; and in the form of her cell, too, she economises space and material.

And yet, clever as these wonderful architects are, they amaze us by their stupidity in the face of the smallest difficulty. On the one hand their instincts teach them to behave like men of science; but on the other it is plain that they are entirely without the power of reflection. I have convinced myself of this fact by various experiments.

The Common Wasp has chanced to set up house beside one of the walks in my enclosure, which enables me to experiment with a bell-glass. In the open fields I could not use this appliance, because the boys of the countryside would soon smash it. One night, when all was dark and the Wasps had gone home, I placed the glass over the entrance of the burrow, after first flattening the soil. When the Wasps began work again next morning and found themselves checked in their flight, would they succeed in making a passage under the rim of the glass? Would these sturdy creatures, who were capable of digging a spacious cavern, realise that a very short underground tunnel would set them free? That was the question.

The next morning I found the bright sunlight falling on the bell-glass, and the workers ascending in crowds from underground, eager to go in search of provisions. They butted against the transparent wall, tumbled down, picked themselves up again, and whirled round and round in a crazy swarm. Some, weary of dancing, wandered peevishly at random and then re-entered their dwelling. Others took their places as the sun grew hotter. But not one of them, not a single one, scratched with her feet at the base of the glass circle. This means of escape was beyond them.

Meanwhile a few Wasps who had spent the night out of doors were coming in from the fields. Round and round the bell-glass they flew; and at last, after much hesitation, one of them decided to dig under the edge. Others followed her example, a passage was easily opened, and the Wasps went in. Then I closed the passage with some earth. The narrow opening, if seen from within, might help the Wasps to escape, and I wished to leave the prisoners the honour of winning their liberty.

However poor the Wasps’ power of reasoning, I thought their escape was now probable. Those who had just entered would surely show the way; they would teach the others to dig below the wall of glass.

I was too hasty. Of learning by experience or example there was not a sign. Inside the glass not an attempt was made to dig a tunnel. The insect population whirled round and round, but showed no enterprise. They floundered about, while every day numbers died from famine and heat. At the end of a week not one was left alive. A heap of corpses covered the ground.

The Wasps returning from the field could find their way in, because the power of scenting their house through the soil, and searching for it, is one of their natural instincts, one of the means of defence given to them. There is no need for thought or reasoning here: the earthy obstacle has been familiar to every Wasp since Wasps first came into the world.

But those who are within the bell-glass have no such instinct to help them. Their aim is to get into the light, and finding daylight in their transparent prison they think their aim is accomplished. In spite of constant collisions with the glass they spend themselves in vainly trying to fly farther in the direction of the sunshine. There is nothing in the past to teach them what to do. They keep blindly to their familiar habits, and die.

II

SOME OF THEIR HABITS

If we open the thick envelope of the nest we shall find, inside, a number of combs, or layers of cells, lying one below the other and fastened together by solid pillars. The number of these layers varies. Towards the end of the season there may be ten, or even more. The opening of the cells is on the lower surface. In this strange world the young grow, sleep, and receive their food head downwards.

The various storeys, or layers of combs, are divided by open spaces; and between the outer envelope and the stack of combs there are doorways through which every part can be easily reached. There is a continual coming and going of nurses, attending to the grubs in the cells. On one side of the outer wrapper is the gate of the city, a modest unadorned opening, lost among the thin scales of the envelope. Facing it is the entrance to the tunnel that leads from the cavity to the world at large.

In a Wasp community there is a large number of Wasps whose whole life is spent in work. It is their business to enlarge the nest as the population grows; and though they have no grubs of their own, they nurse the grubs in the cells with the greatest care and industry. Wishing to watch their operations, and also to see what would take place at the approach of winter, I placed under cover one October a few fragments of a nest, containing a large number of eggs and grubs, with about a hundred workers to take care of them.

To make my inspection easier I separated the combs and placed them side by side, with the openings of the cells turned upwards. This arrangement, the reverse of the usual position, did not seem to annoy my prisoners, who soon recovered from the disturbance and set to work as if nothing had happened. In case they should wish to build I gave them a slip of soft wood; and I fed them with honey. The underground cave in which the nest hangs out of doors was represented by a large earthen pan under a wire-gauze cover. A removable cardboard dome provided darkness for the Wasps, and—when removed—light for me.

The Wasps’ work went on as if it had never been interrupted. The worker-Wasps attended to the grubs and the building at the same time. They began to raise a wall round the most thickly populated combs; and it seemed as though they might intend to build a new envelope, to replace the one ruined by my spade. But they were not repairing; they were simply carrying on the work from the point at which I interrupted it. Over about a third of the comb they made an arched roof of paper scales, which would have been joined to the envelope of the nest if it had been intact. The tent they made sheltered only a small part of the disk of cells.

As for the wood I provided for them, they did not touch it. To this raw material, which would have been troublesome to work, they preferred the old cells that were no longer in use. In these the fibres were already prepared; and, with a little saliva and a little grinding in their mandibles, they turned them into pulp of the highest quality. The uninhabited cells were nibbled into pieces, and out of the ruins a sort of canopy was built. New cells could be made in the same way if necessary.

Even more interesting than this roofing-work is the feeding of the grubs. One could never weary of the sight of the rough fighters turned into tender nurses. The barracks become a crêche. With what care those grubs are reared! If we watch one of the busy Wasps we shall see her, with her crop swollen with honey, halt in front of a cell. With a thoughtful air she bends her head into the opening, and touches the grub with the tip of her antenna. The grub wakes and gapes at her, like a fledgling when the mother-bird returns to the nest with food.

For a moment the awakened larva swings its head to and fro: it is blind, and is trying to feel the food brought to it. The two mouths meet; a drop of syrup passes from the nurse’s mouth to the nurseling’s. That is enough for the moment: now for the next Wasp-baby. The nurse moves on, to continue her duties elsewhere.

Meanwhile the grub is licking the base of its own neck. For, while it is being fed, there appears a temporary swelling on its chest, which acts as a bib, and catches whatever trickles down from the mouth. After swallowing the chief part of the meal the grub gathers up the crumbs that have fallen on its bib. Then the swelling disappears; and the grub, withdrawing a little way into its cell, resumes its sweet slumbers.

When fed in my cage the Wasp-grubs have their heads up, and what falls from their mouths collects naturally on their bibs. When fed in the nest they have their heads down. But I have no doubt that even in this position the bib serves its purpose.

By slightly bending its head the grub can always deposit on the projecting bib a portion of the overflowing mouthful, which is sticky enough to remain there. Moreover, it is quite possible that the nurse herself places a portion of her helping on this spot. Whether it be above or below the mouth, right way up or upside down, the bib fulfils its office because of the sticky nature of the food. It is a temporary saucer which shortens the work of serving out the rations, and enables the grub to feed in a more or less leisurely fashion and without too much gluttony.

In the open country, late in the year when fruit is scarce, the grubs are mostly fed upon minced Fly; but in my cages everything is refused but honey. Both nurses and nurselings seem to thrive on this diet, and if any intruder ventures too near to the combs he is doomed. Wasps, it appears, are far from hospitable. Even the Polistes, an insect who is absolutely like a Wasp in shape and colour, is at once recognised and mobbed if she approaches the honey the Wasps are sipping. Her appearance takes nobody in for a moment, and unless she hastily retires she will meet with a violent death. No, it is not a good thing to enter a Wasps’ nest, even when the stranger wears the same uniform, pursues the same industry, and is almost a member of the same corporation.

Again and again I have seen the savage reception given to strangers. If the stranger be of sufficient importance he is stabbed, and his body is dragged from the nest and flung into the refuse-heap below. But the poisoned dagger seems to be reserved for great occasions. If I throw the grub of a Saw-fly among the Wasps they show great surprise at the black-and-green dragon; they snap at it boldly, and wound it, but without stinging it. They try to haul it away. The dragon resists, anchoring itself to the comb by its hooks, holding on now by its fore-legs and now by its hind-legs. At last the grub, however, weakened by its wounds, is torn from the comb and dragged bleeding to the refuse-pit. It has taken a couple of hours to dislodge it.

Supposing, on the other hand, I throw on to the combs a certain imposing grub that lives under the bark of cherry-trees, five or six Wasps will at once prick it with their stings. In a couple of minutes it is dead. But the huge dead body is much too heavy to be carried out of the nest. So the Wasps, finding they cannot move the grub, eat it where it lies, or at least reduce its weight till they can drag the remains outside the walls.

III

THEIR SAD END

Protected in this fierce way against the invasion of intruders, and fed with excellent honey, the grubs in my cage prosper greatly. But of course there are exceptions. In the Wasps’ nest, as everywhere, there are weaklings who are cut down before their time.

I see these puny sufferers refuse their food and slowly pine away. The nurses perceive it even more clearly. They bend their heads over the invalid, sound it with their antennæ, and pronounce it incurable. Then the creature at the point of death is torn ruthlessly from its cell and dragged outside the nest. In the brutal commonwealth of the Wasps the invalid is merely a piece of rubbish, to be got rid of as soon as possible for fear of contagion. Nor indeed is this the worst. As winter draws near the Wasps foresee their fate. They know their end is at hand.

The first cold nights of November bring a change in the nest. The building proceeds with diminished enthusiasm; the visits to the pool of honey are less constant. Household duties are relaxed. Grubs gaping with hunger receive tardy relief, or are even neglected. Profound uneasiness seizes upon the nurses. Their former devotion is succeeded by indifference, which soon turns to dislike. What is the good of continuing attentions which soon will be impossible? A time of famine is coming; the nurselings in any case must die a tragic death. So the tender nurses become savage executioners.

“Let us leave no orphans,” they say to themselves; “no one would care for them after we are gone. Let us kill everything, eggs and grubs alike. A violent end is better than a slow death by starvation.”

A massacre follows. The grubs are seized by the scruff of the neck, brutally torn from their cells, dragged out of the nest, and thrown into the refuse-heap at the bottom of the cave. The nurses, or workers, root them out of their cells as violently as though they were strangers or dead bodies. They tug at them savagely and tear them. Then the eggs are ripped open and devoured.

Before much longer the nurses themselves, the executioners, are languidly dragging what remains of their lives. Day by day, with a curiosity mingled with emotion, I watch the end of my insects. The workers die suddenly. They come to the surface, slip down, fall on their backs and rise no more, as if they were struck by lightning. They have had their day; they are slain by age, that merciless poison. Even so does a piece of clockwork become motionless when its mainspring has unwound its last spiral.

The workers are old: but the mothers are the last to be born into the nest, and have all the vigour of youth. And so, when winter sickness seizes them, they are capable of a certain resistance. Those whose end is near are easily distinguished from the others by the disorder of their appearance. Their backs are dusty. While they are well they dust themselves without ceasing, and their black-and-yellow coats are kept perfectly glossy. Those who are ailing are careless of cleanliness; they stand motionless in the sun or wander languidly about. They no longer brush their clothes.

This indifference to dress is a bad sign. Two or three days later the dusty female leaves the nest for the last time. She goes outside, to enjoy yet a little of the sunlight; presently she slides quietly to the ground and does not get up again. She declines to die in her beloved paper home, where the code of the Wasps ordains absolute cleanliness. The dying Wasp performs her own funeral rites by dropping herself into the pit at the bottom of the cavern. For reasons of health these stoics refuse to die in the actual house, among the combs. The last survivors retain this repugnance to the very end. It is a law that never falls into disuse, however greatly reduced the population may be.

My cage becomes emptier day by day, notwithstanding the mildness of the room, and notwithstanding the saucer of honey at which the able-bodied come to sip. At Christmas I have only a dozen females left. On the sixth of January the last of them perishes.

Whence arises this mortality, which mows down the whole of my wasps? They have not suffered from famine: they have not suffered from cold: they have not suffered from home-sickness. Then what have they died of?

We must not blame their captivity. The same thing happens in the open country. Various nests I have inspected at the end of December all show the same condition. The vast majority of Wasps must die, apparently, not by accident, nor illness, nor the inclemency of the season, but by an inevitable destiny, which destroys them as energetically as it brings them into life. And it is well for us that it is so. One female Wasp is enough to found a city of thirty thousand inhabitants. If all were to survive, what a scourge they would be! The Wasps would tyrannise over the countryside.

In the end the nest itself perishes. A certain Caterpillar which later on becomes a mean-looking Moth; a tiny reddish Beetle; and a scaly grub clad in gold velvet, are the creatures that demolish it. They gnaw the floors of the various storeys, and crumble the whole dwelling. A few pinches of dust, a few shreds of brown paper are all that remain, by the return of spring, of the Wasps’ city and its thirty thousand inhabitants.