only to sit on a park bench all day.

Getting stuck in denial is common in 'cool' cultures (such as in

Britain, particularly Southern England) where expressing anger

is not acceptable. The person may feel that anger, but may then

repress it, bottling it up inside.

Likewise, a person may be stuck in permanent anger (which is

itself a form of flight from reality) or repeated bargaining. It is

more difficult to get stuck in active states than in passivity, and

getting stuck in depression is perhaps a more common ailment.

Going in cycles

Another trap is that when a person moves on to the next phase,

they have not completed an earlier phase and so move

backwards in cyclic loops that repeat previous emotion and

actions. Thus, for example, a person that finds bargaining not to

be working, may go back into anger or denial.

Cycling is itself a form of avoidance of the inevitable, and going

backwards in time may seem to be a way of extending the time

before the perceived bad thing happens.

Source: Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying, Macmillan,

NY, 1969

http://changingminds.org/disciplines/change_management/ku

bler_ross/kubler_ross.htm

1093

Examples.

Shock and Denial.

"This can't be happening, not to me."; "I don't have true

infertility since I've already had a child."

Denial is a conscious or unconscious refusal to accept facts,

information, reality, etc., relating to the situation concerned. It's

a defence mechanism and perfectly natural. Some people can

become locked in this stage when dealing with a traumatic

change that can be ignored.

Anger.

"Why me? After all I've been through. It's not fair!"; "How can

this happen to me?"; '"Who is to blame?"

Anger can manifest in different ways. People dealing with

emotional upset can be angry with themselves, and/or with

others, especially those close to them. Knowing this helps keep

detached and non-judgemental when experiencing the anger of

someone who is very upset.

1094

Bargaining.

"Please God. I would give anything."; "If I don't get pregnant we

will just adopt, either way it will happen."; "I know there must

be a reason this is happening."

Traditionally the bargaining stage for people facing

death can involve attempting to bargain with whatever God the

person believes in. People facing less serious trauma can bargain

or seek to negotiate a compromise. For example "Can we still be

friends?.." when facing a break-up. Bargaining rarely provides a

sustainable solution, especially if it's a matter of life or death.

Depression.

"I'm so sad, why bother with anything?"; "No matter what I do

it's just not going to happen."; "Why try anymore?"; "Everyone is

moving on without me."

During the fourth stage, the dying person begins to

understand the certainty of death. Because of this, the individual

may become silent, refuse visitors and spend much of the time

crying and grieving. This process allows the dying person to

disconnect from things of love and affection. It is not

recommended to attempt to cheer up an individual who is in this

stage. It is an important time for grieving that must be processed.

Acceptance.

"It's going to be okay."; "There's nothing I can do to change it so

why stay bitter?"; "It will happen eventually."

In this last stage, individuals begin to come to terms with

their mortality, or that of a loved one, or other tragic event.

1095

Not everyone even that has gone through infertility, loss of a

loved one, or a preemie may experience these stages. Some are

strong enough to be in acceptance for most of the time...oh gosh

how I wish I could be that strong. Some will deny it until those

two lines appear or until their baby comes home. But I can

guarantee that I have felt each stage and most do. Some days its

easy to accept and other days I just refuse to accept this. Either

way I will be real about those feelings be that good, bad or ugly.

And I refuse to apologize for that.

http://drawingablake.blogspot.com/2011/12/grief-cycle-and-

loss-of-control.html

Recognizing Grief Over the Loss of Income

Shock and denial are the first reactions of people

experiencing unplanned changes.

When people experience a major income loss they go through

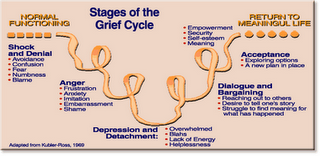

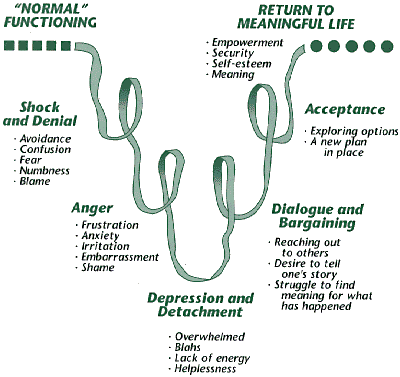

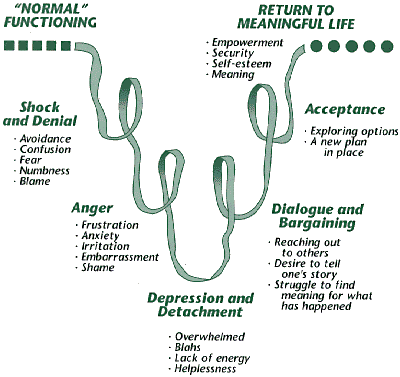

certain stages of grief. Figure 2 shows these and what happens at

each stage. People often move back and forth between the stages

and sometimes get stuck at a particular stage for a while.

To express anger in a positive way, people need to change

how they view the situation.

Stage 1 - Shock and Denial

Shock and denial are the first reactions of people experiencing

unplanned changes. At this stage in the loss cycle, it is normal for

people to feel confused and afraid, and to want to place blame.

However, many people are just numb when facing an unplanned

change as if they were on automatic pilot. It is very common for

people to avoid making decisions or taking action at this point.

1096

Figure 2. Stages of the Grief Cycle

People are often unable to function or perform simple, routine

tasks during this stage.

Denial can occasionally be healthy for a short time, but

prolonged denial can have devastating consequences for the

person and for the situation. Denial of something that has

happened or of the pain and fear being experienced is a way in

which people protect themselves when faced with a painful

situation. Continued denial of the pain and fear, however, will

block them from doing something about it.

1097

Stage 2 - Anger

Anger is a feeling that is often intensely felt during this time.

Anger is identified by feelings of second-guessing, hate, self-

doubt, embarrassment, irritation, shame, hurt, frustration, and

anxiety. People usually understand more clearly what is

happening, but they may look for someone to blame at this stage.

If there is no one on whom to focus the anger or blame, a feeling

of helplessness may take over and the anger may be turned

inside. Some people take it out on themselves by taking

responsibility for a situation over which they have had little

control.

People are often afraid that if they let themselves acknowledge

the anger they feel, they will immediately need to express it and

act on it in a way that they will regret later. However, by not

admitting to themselves and others close to them the loss and

pain they feel, they will be blocked from doing something about

the situation. It will also prevent them from moving on. Some

people get stuck at this stage.

To express anger in a positive way, people need to change how

they view the situation. It is also helpful to talk to others about it

or write down their feelings in order to figure out what they

need to do to make the feelings less intense. Another option is to

turn the anger into energy through an active sport or brisk

physical activity or to express it through playing a musical

instrument.

Stage 3 - Depression and Detachment

The third stage of the loss cycle, depression and detachment, is

characterized by feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and

being overwhelmed. People often feel down, lack energy, and

have no desire to do anything. Withdrawal from activities and

other people is common. Because it is also hard to make

1098

decisions at this stage, ask a family member, friend, or

professional to help you if important decisions need to be made.

Stage 4 - Dialogue and Bargaining

The fourth stage, dialogue and bargaining, is a time when people

struggle to find meaning in what has happened. They begin to

reach out to others and want to tell their story. People become

more willing to explore alternatives after expressing their

feelings. They may, however, still be angry or depressed. People

do not move neatly from one stage to another. Rather, the stages

overlap and people often slip back to earlier stages.

Stage 5 - Acceptance

At this stage, people are ready to explore and consider options.

As the acceptance stage progresses, a new plan begins to take

shape or, at the very least, people are open to new options.

Getting Back to "Normal"

A person's "normal" state of functioning becomes disrupted by a

sudden income loss. It is possible to return to a purposeful state

of functioning after going through the stages described above

and after exploring options and setting a plan. People then begin

to feel secure and in control and have a more positive self-

esteem. People get renewed energy to tackle life again but in

different ways than before the sudden income change. It is

perhaps better to think of the end of the grief cycle as returning

to a meaningful life rather than returning to a "normal" life.

"Normal" at this stage will not be the same as "normal" before

the loss.

Source: University of Minnesota

http://www.extension.umn.edu/distribution/businessmanagem

ent/components/06499c.html

1099

4.13 Knowing and Not Knowing

If I don't know I don't know

I think I know

If I don't know I know

I think I don't know

Laing R D (1970) Knots Harmondsworth; Penguin (p.55)

"He that knows not, and knows not that he knows not is a fool.

Shun him

He that knows not, and knows that he knows not is a pupil.

Teach him.

He that knows, and knows not that he knows is asleep

Wake him.

He that knows, and knows that he knows is a teacher.

Follow him."

(Arabic proverb)

NEIGHBOUR R (1992) The Inner Apprentice London; Kluwer

Academic Publishers. p.xvii

"We know what we know, we know that there are things we do

not know, and we know that there are things we don't know we

don't know"

Donald Rumsfeld (4 Sept 2002) (Woodward, 2004: 171)

It is ironic, perhaps, that the initial insight is allegedly Arabic.

This paper is playing around with a conceit: two senses of the

term "know". However, it is all in a professional cause.

1100

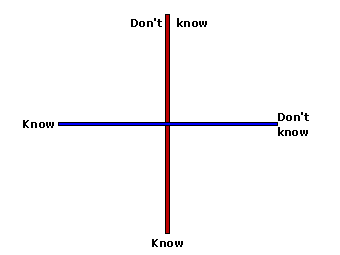

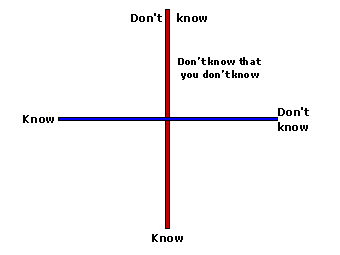

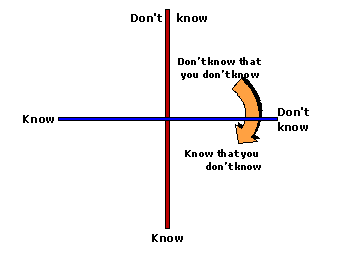

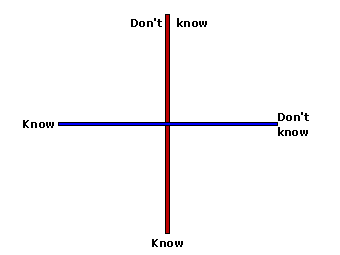

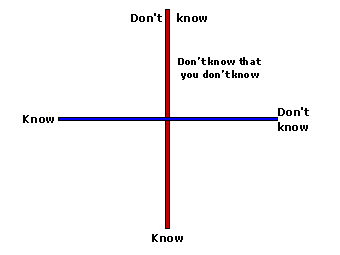

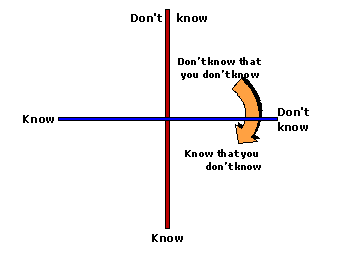

The two senses are those of:

awareness of self, (represented by the vertical red line

in the diagram below) and

knowledge of the world (the horizontal blue line)

There are of course four possible combinations, which are

explored below.

You may find parallels with the witting and willing practice

model, and also with the familiar "unconscious incompetence"

to "unconscious competence" model. which relates primarily to

practical skills: here we are exploring knowledge. Laing's poetic

exploration of its interpersonal convolutions cited above (it goes

on for another 21 pages), and the citation of the idea by

Neighbour (1992) credited as an Arabic proverb demonstrate

that it has a considerable provenance.

1101

Not knowing you don't know

The first possibility is that of being unaware that you don't know

something. This is the "ignorance is bliss" state, enjoyed by

everyone who pontificates about politics in pubs. It is also the

position of many people on "soft" occupations (such as teaching,

or social work) which look from the outside as if "any fool could

do it". (Some do.) And it is engendered by consummate

professionals who make what they do look easy (such as

plasterers and chefs and popular novelists and...).

Many students start from this position, and although the

Neighbour proverb calls them "fools", it is not really fair. Let's go

on —

So the first move is often to make learners aware of their

ignorance. This is tricky, in practice. Unless they are a captive

audience it is quite easy to frighten them off. (It is also quite

seductive, because it is a chance to show off your own level of

knowledge or competence.) On the other hand, it is a crucial step

in developing motivation to learn.

1102

There are various ways of doing it.

In my first German lesson, a young teacher recited a poem

to us in German: it sounded great, but we couldn't

understand a word of it, of course. He didn't really need to

do it, because we already knew we didn't know any of it

apart from a couple of phrases picked up from war films.

He was trying to show what we might aspire to, and went

on to explain that. (It must have made an impact because I

can remember the lesson fifty years later.)

You can ask a student (usually either one who is a bit

full of himself and needs to be "taken down a peg", or

one who is mature enough not to be humiliated) to do

something practical in the certainty that he will fail.

Only do this if you are confident that when you do it, as

you will be challenged to, you can manage it yourself.

You can pose a problem which has a seemingly simple

answer (political, economic, legal—or in Neighbour's

case, medical), and then show the problems in reaching

1103

that simple solution, which stem from ignorance of the

context.

The trick is to show something which is (so far) beyond the

students' reach, but not so far beyond it that they will despair.

The second trick is to make it interesting. I have deliberately not

mentioned strategies for doing this in accountancy.

More significantly:

In continuing professional development courses in

particular, you may be challenging survival-oriented

practice in which people have a substantial vested

interest: this is the key to the whole un-

learning/learning process.

Unless you have to do it, don't. Many learners

(particularly those who have signed up for your course

of their own free will) are only too aware of what they

don't know. The last thing they need is for you to rub it

in.

Skill in this area is of course a core competence for

charlatans. Whether self-help gurus who must convince

you of your personal inadequacy or potential ill-health,

religious proselytisers who must convict you of sins

only they believe are sinful, or salespeople who have to

create a "need" for their product, they all have to

manage this stage. Study and learn from them—just

don't believe them.

1104

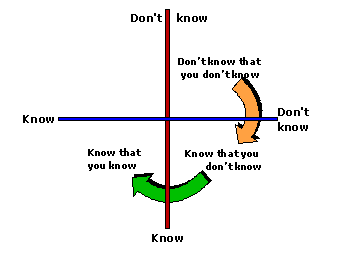

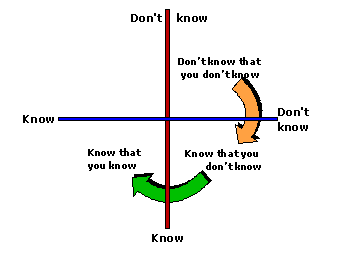

Knowing you don't know

This move, from "knowing that you don't know" to "knowing

that you know" is what most learning and hence teaching is all

about.

1105

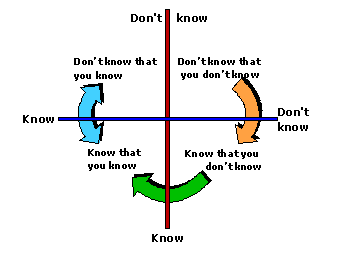

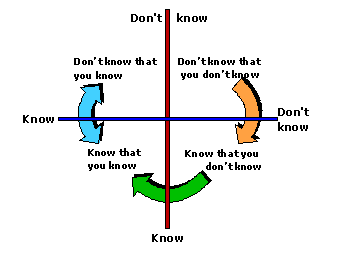

Knowing and not knowing that you know

The interaction between knowing and not knowing that you

know is however more complex and much neglected.

There are two kinds of knowledge (in a third sense) or

practice involved here.

The first is that for which the move to "not knowing

that you know" or "unconscious competence" is the

highest stage of development. This applies to the basic

skills of driving, or knitting; the kind of thing you can

"do without thinking".

The second is where people who have informally

learned a great deal mistakenly put themelves in the

"knowing that they don't know" category because they

have never received any academic or professional

accreditation for their learning. This is the downside of

our qualification-driven culture, which dismisses those

whom Gramsci called "organic intellectuals" because

they do not have the recognition of the formal

educational system.

Neighbour's Arabic proverb enjoins us to "awaken"

someone in this position, which means to take them

back, counter-clockwise on the diagram, to an

awareness of their knowledge. There is a link here with

Mezirow's concept of "transformative learning", in

which education leads to a re-evaluation of life so far.

(There is perhaps a third possibility here, too, which is

the fit with the willing but unwitting category in the

model of practice on this site.)

1106

The problematic expert

The fourth possibility is touched on in the discussion of

expertise.This the person who (wait for it!) knows that she knows

but does not know how she knows—or cannot express it. Ask

about a particularly brilliant bit of practice and you will get a

banal answer which might have come out of the textbook, but

which totally fails to do justice to the complexity of what she has

done. Sometimes that answer will be given because she does not

want to appear a "smart-arse" ("Ass" if you are American, but I

wouldn't wish to confuse you with references to donkeys.)

Sometimes, though, she might claim that it is a matter of "not

being able to put it into words" or even, disconcertingly, of a

"hunch".

She may even be afraid of trying to express her expertise, for fear

that an inadequate exposition will somehow jeopardise fragile

knowledge. Once she has said it, it might become ossified. She

might feel obliged to live up to her exposition and limit that

insight and creativity which goes beyond words.

Some things we can teach, and some we can't.

1107

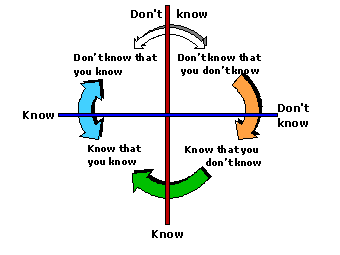

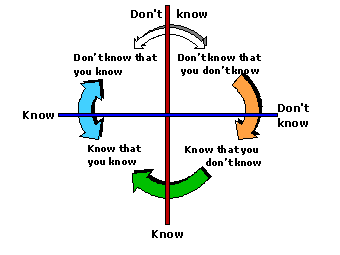

So that's the whole story. Or is it? Is there any connection

between the "Don't know that you know" stage and the "Don't

know that you don't know" stage? Possibly (but not always).

There may occasionally be a cycle: if you don't know

what you do know, you probably don't know what you

don't know, either. This may be the case for people who

are stuck at a survival learning level. They have learned

to get by with what they know, to the extent that they

do not give themselves credit for it, or are even

unaware of knowing it, as we have discussed. However,

they can't take it any further because it is out of

awareness, so they are unaware of how they could

move on from mere competence or proficiency to real

expertise.

For such people, because they do not know what they

know, they may be unsure of their knowledge, and may

be threatened by the prospect of moving on, which

leads to a degree of resistance to new learning.

The Bottom Line

Clearly we have to get people to realise what they don't know, if

necessary. But fascinating though it is, the inarticulate expertise

of not knowing that you know is a dead end from the learning

and teaching point of view. The only open position, with

potential for development, is that of knowing what you know.

Sources:

http://www.trainer.org.uk/members/theory/

process/stages_of_learning.htm

http://www.neurosemantics.com/Articles/

Unconscious.htm

http://www.nlp.org/glossary.html#U

Dubin, P (1962) 'Human Relations in Administration',

Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall

1108

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1971). A practical guide for supervisory

training and development. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley

Publishing Co.

There's a fascinating exploration of the whole story at

http://www.businessballs.com/consciouscompetencelearn

ingmodel.htm

The medical school at the University of Arizona has taken similar

ideas further with their Curriculum on Medical Ignorance (CMI)

and developed the Q-Cubed; Questions, questioning and

questioners project. Here is their "Ignorance Map", which

identifies:

Known Unknowns: all the things you know you don't

know.

Unknown Unknowns: all the things you don't know you

don't know

Errors: all the things you think you know but don't

Unknown Knowns: all the things you don't know you

know

Taboos: dangerous, polluting or forbidden knowledge

Denials: all the things too painful to know, so you don't

[acknowledgements to Perkins D (2009) Making Learning

Whole: how seven principles of teaching can transform

education San Francisco; Jossey Bass p 241 for the link.]

Ref: WOODWARD B (2004) Plan of Attack New York; Simon and

Schuster

1109

Source:

Atherton J S (2011) Doceo; Knowing and not knowing [On-line:

UK] retrieved 1 February 2012 from

http://www.doceo.co.uk/tools/knowing.htm

Read

more:

Knowing

and

not

knowing

http://www.doceo.co.uk/tools/knowing.htm#ixzz1l7YFrgpN

Under Creative Commons License: Attribution Non-Commercial

No Derivatives

conscious competence learning model

stages of learning - unconscious incompetence to

unconscious competence - and other theories and models for

learning and change

Here first is the 'conscious competence' learning model and

matrix, and below other other theories and models for learning

and change.

The earliest origins of the conscious competence theory are not

entirely clear, although the US Gordon Training International

organisation has certainly played a major role in defining it and

and promoting