Chapter 4: the Routine System

A new system

Once I gave some thought to the paper on which I had written out my work plan for the week. It was divided into several sections: crisis situations, current, upcoming, and ideas. Later I added one more sections: goals.

I started thinking about why the list was laid out the way it was and understood that its layout allowed me to quickly look over everything happening at work. Within minutes I could see what I needed to do and what was really necessary, and it dawned on me: there were my priorities. I had the feeling I had found something, even though the picture at the time was still dim, leaving much to be hashed out.

What the word “routine” means to me

I would like to immediately clarify that the word “routine” means something a bit different to me than it does to others. As I looked over the projects and goals I had in one of my sections I knew that I could not avoid doing them without incurring consequences.

People usually think that a routine is something they do every day or have to do that is boring and best to just finish as fast as possible. For me, however, routine is consistency. We go to work at the same time every day, we wake up and go to sleep, eat lunch, eat dinner, clean the house, buy groceries, do the laundry, and so much more. When we do all that haphazardly or just whenever we feel like it, sooner or later we have issues.

I am not just talking about a regimen; I am referring to a normal and regular order for a given area of your live. We can use work as an example. There is a minimum that needs to be done: arrive at a given time, work no less than eight hours, and carry out some sort of plan. All of that is your work routine.

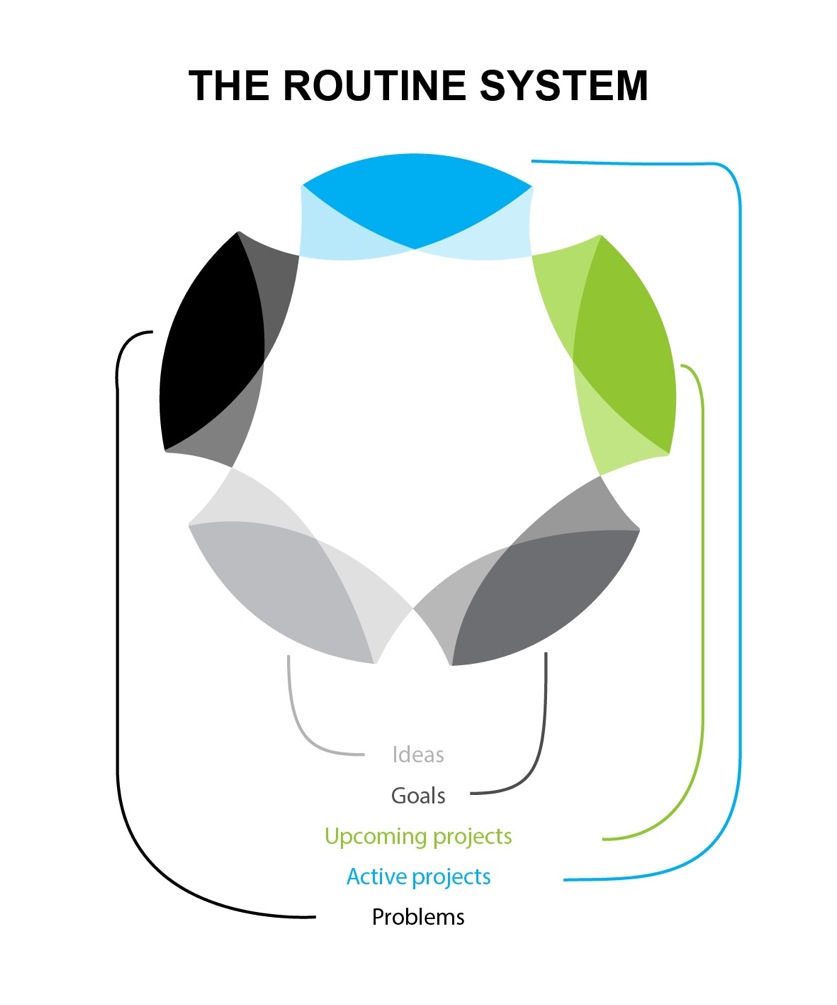

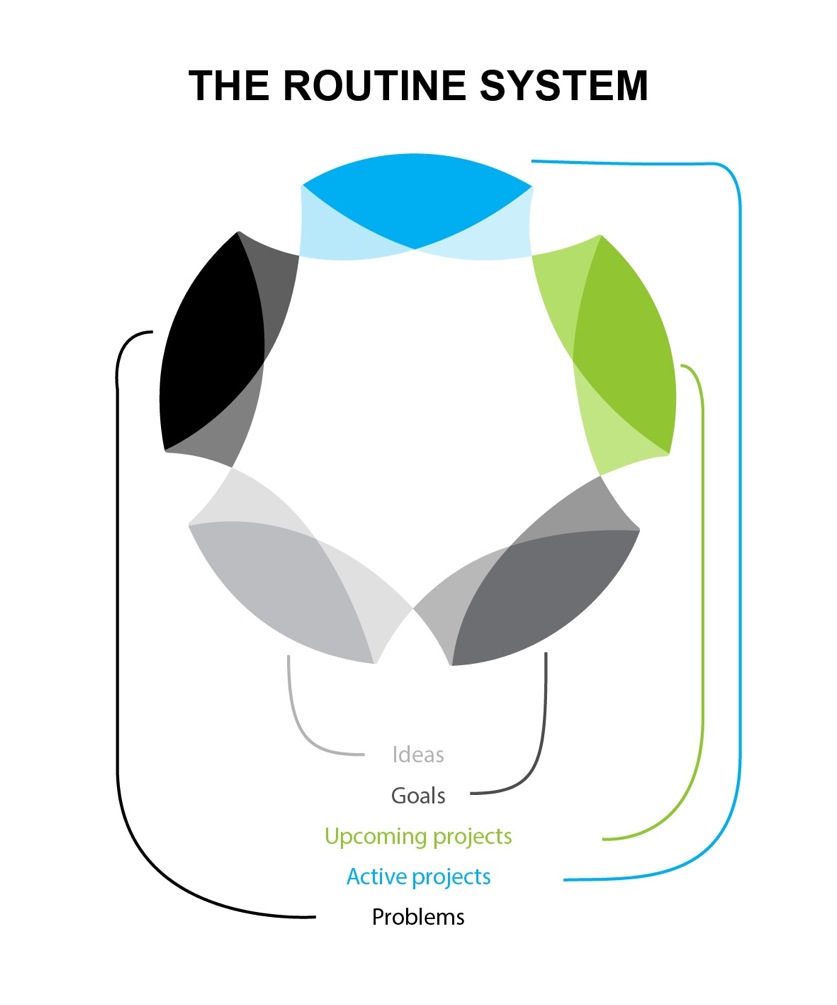

I started imagining my routine as a wheel that must continue spinning so that everything is in order. There are, however, some things that can slow it down or stop it from spinning altogether, though there are also other things that facilitate how it works. Let’s look at both those factors.

Active projects

The main element of a routine is your active projects (the “current” section I talked about at the beginning of the chapter), which are what require action right now. These are the projects you cannot avoid doing, are personally responsible for, and would suffer consequences for not doing.

What projects can we include here?

1. “Order gas.” If I do not do this within a week, it may run out and we will not be able to cook or even heat up food.

2. “Pay the electricity bill.” If we do not pay on time, we may be fined or have our electricity shut off.

3. “Buy a printer cartridge.” If I put this off, we will not be able to print important documents.

These examples show that putting these types of things off leads to unnecessary wastes of time or money as well as other problems. I think it is clear what belongs in the projects list.

Problems

Everything that interferes with your routine belongs here. Usually these types of things have strong negative consequences and can put the brakes on your wheel or stop it completely.

For example, if we do not buy groceries for this week, we will have to stop by a 24 hour store where the prices are higher. Ultimately, moving away from one’s routine leads to problems and crises.

Of course, there is no avoiding problems completely, seeing as how they will always pop up somewhere. That is why we have this section in the list: problems are your number one priority, given the fact that they often come with their own consequences. They need to be resolved as soon as possible so as not to interfere with your everyday routine.

Upcoming projects

We always have projects that have yet to begin, though we know for sure that after a certain period of time they may become active projects. They often do not have a set date, but can still become important and necessary at any moment. If we do not pay attention to them in time, they will most likely cause problems.

Upcoming projects should move to active projects before they lead to crises and problems.

Recognizing this helped me clarify my priorities, as I first had to deal with problems, then routine tasks, and then turn to upcoming projects.

Conclusions:

Your routine is made up of upcoming projects, active projects, and problems—in other words, everything that requires something of you now or in the near future to avoid negative consequences.

Now let’s talk a little about ideas and goals, both of which I mentioned at the beginning of this chapter.

Ideas

When I started thinking of my routine as a wheel, it was important to understand the role played by ideas and goals. How do they affect our everyday routine?

Most difficult for me was separating ideas and goals from my routine, though understanding the difference between them was no walk in the park either.

So why do we call one task an idea and another a routine project? I was generally able to tell the difference intuitively, but laying out clear criteria was another matter altogether. Another issue was that some things seemed to straddle the border between the two concepts, some even leaking over into problem territory. I started thinking about delineating them in time: for example, how soon do I need to accomplish a certain task or project?

That led me to the following time frames:

1. Problems are very urgent and need to be done today, right now, or tomorrow at the latest.

2. Active projects need to be done today, tomorrow, or this week.

3. The upcoming projects category encompasses a wide variety of deadlines, but is generally for things that need to happen this month or next.

4. Goals can occur this year or not at all.

5. Ideas may or may not occur in general.

By then my to-do list in ToodLedo had grown to over 300 items, a number that in itself was causing me stress. Way back when I was mastering GTD everything just moved around into separate lists and laid there like dead weight. Instead, I now started taking different items from my list and asking myself five simple questions I had puzzled out of my time-based analysis and criteria:

1. What happens if I do not do it today?

2. What happens if I do not do it tomorrow?

3. What happens if I do not do it this week?

4. What happens if I do not do it this month?

5. What happens if I do not do it at all?

You can always modify these questions to fit your situation, with problems for some people ranging from one hour to one week. Everything depends on the tempo and intensity of your life in addition to the situations themselves. Regardless, I think that for most people problems are what need to be resolved today or tomorrow at the latest.

So I got to work seeing how my list fit within these questions, crossing out what turned out to be unnecessary. Imagine my surprise when I found that more than half the items on my list were nothing more than ideas for which I answered a hearty “nothing!” when asking the question, “What happens if I do not do it at all?”.

In the end I found what I had been looking for: a fast and understandable way to figure out whether we are dealing with ideas or projects.

For me that was a huge breakthrough I exploited to learn how to quickly differentiate between ideas and my routine. But how do ideas influence a routine? Are ideas good or bad for our everyday routine? Do they get the wheel moving faster or slow it down?

In chapter two I talked about my friend who needed some help. He was feeling a lot of stress due to the amount of urgent things he had do, so we set to work using the Routine System to help him out.

His first item was buy exercise sneakers for the entire family. I asked him, “What happens if you never do this?” He smiled and answered that nothing would happen most likely, and with that he understand that it was just an idea. We went point by point asking the same question and soon saw that his list of urgent things to do was almost completely ideas. This question was crucial for him.

What conclusion can we make from all that? Most importantly we need to understand that many people put together huge laundry lists of things to do without even suspecting that a good half of the items on those lists are nothing more than ideas. We are generally unable to distinguish ideas from important projects, possibly because our feelings often fool us. Allow me to demonstrate.

A friend mentioned that this question and understanding what an idea is helped him avoid an unnecessary expenditure at work. He had a colleague who liked buying new technology, using it, figuring it out, and then selling it to someone else at a discount so he could buy a newer model. Once he offered his co-workers a video camera cheaper than it cost in the store. My friend thought it might be a good idea to buy it, seeing as how it was a good deal. The next day this guy lowered the price, and the following day halved it. My friend was ready to take the bait hook, line, and sinker when our question popped into his head: “What happens if I never do this?” The answer was immediate and clear: nothing at all. He realized he was wrapped up in an idea, though he was able to stop in time to avoid buying something he did not need.

What can we learn from this story? Ideas are often build not on our needs, but on our emotions. You instinctively think that you need to make the purchase, but if you ask yourself what will happen if you do not, you will see the situation in a completely new light.

So ideas are fantasies that we can characterize as “What if…?” Ecclesiastes 11:4 reads, “Whoever watches the wind will not plant; whoever looks at the clouds will not reap.” This means that when we get engrossed in ideas we stop doing what is actually important, instead spending our time on more dubious enterprises.

Ideas can be quite dangerous, sapping your energy, money, and, what is worse, your time. We are often in the power of our emotions, entranced with the thought of sating our urges.

I would like to share another story. Once another friend called and asked if I knew how to use ProShow, a professional program for making slide shows. I asked him what he was trying to do.

It turns out the next day he had a party at work and wanted to make a slideshow out of 300 pictures he had accumulated working there. I immediately understood what was going on and asked him what would happen if he did not make the slideshow. After thinking for a bit he answered that nothing would happen, though he said he would like to do something fun with the pictures for his co-workers.

I suggested the simplest possible option: writing the pictures to a DVD and showing them as a slideshow. “But what about the music?” he asked. I answered that he could add that in separately, and we had a deal. In the end my friend spent all of 15 minutes showing the pictures to his colleagues instead of the hours he would have spent figuring out the program. Everyone was happy.

What can we take from this story?

It is becoming clear that an ill-advised focus on ideas can lead to unnecessary wastes of energy, money, and time, while maintaining a well-balanced focus can yield excellent results. That means that under certain circumstances ideas can slow and even stop the wheel of our routine, while under others they can grease it.

You should never stop your routine for an idea or allow them to cause problems, something that often happens. Imagine that you need to pay your water bill right away—this is your final notice, to make it worse—and if you do not do so, your water will be shut off. Suddenly the idea crosses your mind that you might be able to pay online. You sit down and find the site, though it turns out that your computer is having trouble with it because you need to update Flash. You try to get that done, but for some reason it is just not happening. Now you start looking through forums and googling “What should I do if my computer isn’t loading a site?” Two or three hours later it hits you that you should just pay at the post office, but by now it is already closed. Have you had situations like this one? I have many times. This is what happens when you do not learn how to differentiate ideas.

Conclusions

We now know that ideas are not what needs to be done right away, making it important to understand if an item on our list is an idea or a routine task. To do that we ask the question, “What happens if I do not do this?” We also figured out that if we would really like to work on an idea in our life for which enjoyment is more important than a result, we should try to spend as little as possible.

But what should you do if you can tell that implementing an idea will take a lot more than ten or 15 minutes? Now we need to understand the difference between ideas and goals and how ideas can get moved to our list of goals.

Goals

For a long time I was not able to understand how ideas differ from goals and goals from our routine, or active projects. Sometimes I thought the entire goals category was unnecessary. For a while I put ideas I considered important and needed in the active projects folder. Later, however, I realized that those projects were not getting done, as there was always something else to do first. I started thinking about each of those ideas I had stuck into the active projects folder that had become nothing more than dead weight.

For example, I wanted to boost my level of English and master Photoshop, though I did not have a clear plan for how to do either of those things.

I understood that these projects would improve my everyday routine: English would give me access to information not available in Russian, while Photoshop would provide more income and career opportunities. While these projects would both be very useful for me, they were related to different aspects of my life. I needed English for my personal development, while Photoshop was for my career.

That helped me understand that I needed a goals folder to help me focus on and develop different areas of my life.

Those areas could be health, work, career, family, hobbies, and much more.

The ideas or tasks you think could improve different aspects of your life and yield benefits in the future can be moved to the goals folder.

Later we will talk in more depth about how ideas can become goals and goals can become active projects.

Of course, one might ask, “Why do we need to split tasks into ideas and goals? Wouldn’t it be simpler to just throw them all into one folder and use that to take care of everything at the same time?” No, it would not be simpler.

First of all, we are talking about priorities, and moving everything into one folder risks missing out on something that is really important. Ideas are your lowest priority given that they do not lead to potential consequences. Goals are more valuable than ideas, as they are aimed at improving the different areas of our life.

Second, mixing ideas and goals into a single list will lead to the stress of watching them sit there day after day giving you the impression that you have a ton to do.

I sometimes go long periods of time without checking up on my lists of ideas and goals, but I feel much better because I know that they are where they belong, are not forgotten, and will have their turn in the sun.

Even so, my productivity did not drop; in fact, I found I was doing more. That happened because I had previously been scattering myself across many different things, jumping from one to the other, forgetting about my everyday life, and creating crises. I now knew how to keep from trying to implement too many ideas in my life thanks to first thinking through and understanding them, a process that yielded much better results.

Conclusions:

Goals are ideas that can simplify and improve your routine. This means that goals can grease our routine wheel, making it spin faster and longer. We also learned that goals relate to different areas of our lives.

Wrap-up

In this chapter we looked at how the Routine System is built, going over its five basic points:

1. Problems

2. Active projects

3. Upcoming projects

4. Goals

5. Ideas

Problems, active projects, and upcoming projects help the wheel of our daily routine turn.

Unexpected ideas, on the other hand, can slow or even bring it to a stop. Ideas can become goals, which in turn become active projects.

Having gone over the theory behind the system, let’s talk about how it works in practice.