Discovering U.S. Empire through the Archive

An important turn in American Studies over the past twenty years has begun to read U.S. expansionism in the nineteenth century as part of a larger imperialist project. Whereas older histories tended to coordinate the U.S.’s territorial growth with the spread of democracy across the Americas, the “New American Studies,” as it came to be called, saw in it an aggressive desire for economic and political domination that echoed contemporary European imperial powers. The established historical narrative largely accepted that at the turn of the century the Spanish American War, during which the U.S. occupied such locales as Cuba and the Philippines, marked a turn in U.S. political activity toward an imperialist-inflected globalization. However, newer critics now pointed toward earlier instances, including the U.S.-Mexican War and the subsequent appropriation of vast Mexican lands, as manifestations of U.S. imperialism. Moreover, in their studies, they applied the paradigms of imperialism to longstanding U.S. practices such as Native American removal and African slavery. One of the earliest significant works to mark such a shift in scholarly perception was a collection of essays entitled Cultures of United States Imperialism, edited by Amy Kaplan and Donald Pease. Several studies followed that took seriously the proposal that the nineteenth-century U.S. operated as an empire, including Malini Schueller’s U.S. Orientalisms: Race, Nation, and Gender in Literature, Shelley Streeby’s American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture, and Eric Sundquist’s Empire and Slavery in American Literature. What most of these works shared in common was that they emerged from the field of cultural studies, rather than from a straight historical perspective. Indeed, the concept of nineteenth-century U.S. imperialism has had a profound impact on cultural studies, as critics began to interpret literary and artistic productions in terms of either their participating in or critiquing the U.S. as empire.

The ‘Our Americas’ Archive Partnership, a collection of rare documents that promotes a hemispheric approach to American Studies, contains a host of writings that places the nineteenth-century U.S. within a broader network of inter-American relations, whether they be economic, political, or cultural. As such, this archive will prove to be of particular value to scholars and students who wish to track the long history of U.S. imperialism. It possesses an especially rich amount of content on the state of U.S.-Mexican relations during the early-to-mid nineteenth century, particularly as they revolved around the contested Texas territory. One such document is the travel journal of Mirabeau B. Lamar – held physically in the special collections library at Rice University – which offers a ground level view of the tensions in 1835 between Mexico and the emerging Republic of Texas. Lamar fought for Texas independence at the Battle of San Jacinto and was named Sam Houston’s Vice President once Texas was declared a republic. In 1838, Lamar was chosen to succeed Houston and became the second President of the Republic of Texas. He fought in the U.S.-Mexican War and was cited for bravery at the Battle of Monterey. Toward the end of his life, from 1857 to 1859, he served as the Minister to Nicaragua under President James Buchanan. Several schools throughout Texas are now named in his honor. In addition to being an accomplished politician and soldier, Lamar was a prolific writer during his lifetime, authoring not only travel narratives but a great deal of poetry as well. For a thorough account of his life and writings, see Stanley Siegel’s biography, The Poet President of Texas: The Life of Mirabeau B. Lamar, President of the Republic of Texas.

Lamar was participating in a popular nineteenth-century literary genre in authoring his travel journal. The most popular travel narratives produced in the late nineteenth generally involved journeys to foreign lands, usually Europe or the Holy Land. It was not uncommon during the first half of the century, however, for U.S.-authored travel narratives to focus on domestic sojourns, particularly ones to the nation’s ever shifting western frontier. Lamar begins by declaring his intention to settle in Texas if he can discover there a profitable opportunity for himself. His travel journal follows his journey from Columbus, Georgia to Mobile to New Orleans to Baton Rouge to Natchitoches, Louisiana and finally into Texas. At each stop, he provides an extended history of the area along with an account of the contemporary social, religious, and cultural practices that he is able to observe. His “histories” operate through a combination of formal, official facts and local, often humorous anecdotes. Before it arrives at his experiences in Texas, the longest section of Lamar’s journal is the one concerned with the city of New Orleans. He moves frequently between histories of the region, including a long history on the settlement of the Louisiana Territory in general, and his observations of everyday life in the city. Interestingly, he spends a great deal of time on the city’s churches and various religious sects, leading him to comment, “The Methodist I believe are the only sect that has sincerely done any thing for the negroes; a large portion of their congregation and members are black” (13). What is especially noteworthy about this passage is that marks one of the only instances in which Lamar mentions the presence of African Americans in his text. Unlike many other travel narratives of the time, Lamar’s is barely concerned with the issues of slavery or relations between black and white populations. It is certainly not around the issue of slavery that Lamar’s journal provides us with insight into U.S. imperialist ideology. Instead, we must look to his treatment of both American Indians and Mexico in order to excavate the specters of U.S. empire from his writings.

Lamar encounters several Native American tribes during his journey to Texas, including the Comanche and the Caddo. He writes at greatest length about the Comanche, whom he primarily characterizes by their warlike and nomadic natures. It is the latter quality that feeds into Lamar’s indirect justification of the U.S.’s continued westward expansion. He writes, “All the beauties and blessings of nature, all the blessings of industry; all the luxuries that God and art have contributed to place within the reach of man, despised and unheeded by this iron race who seem to have no aim ambition or desire beyond . . . the uncouth wildness of native liberty & unrestrained lisence” (55). Lamar’s implication is that if tribes such as the Comanche will not take advantage of the productive land all around them, then another group of people – namely white Americans – should be able to. He deploys much the same rhetoric when discussing the population he terms the “natives” of Texas, whom he describes as the product of intermarriage between Spaniards and the region’s Indians. First, he racializes them, differentiating them based upon the darkness of their skin: “They are of dark swarthy complexion, darker than the inhabitants of old Spain & not possessing the clear red of the Indians” (37). He goes on to name these people among the laziest in the known world, claiming, “These people have long been in possession of the fairest country in the world . . . and yet from their constitutional & habitual indolence & inactivity they have suffered these advantages to remain unimproved” (38). In order to explain the mass migration of Americans into this region, he portrays Texas as an uncultivated territory waiting upon the arrival of an eager and industrious population. Again, Lamar is operating within a long discursive tradition that uses unexploited economic opportunity as a rationale for imperialist projects.

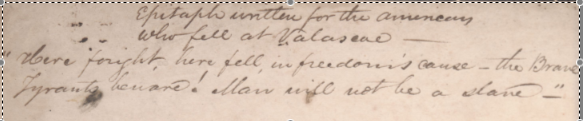

Lamar reserves his praise of Native Americans for the lost Aztecan and Mayan societies of Mexico. Evaluating the state of these societies at the time of Hernándo Cortés’s invasion, he writes, “This is manifest from the stupendous works of arts and monuments of ingenuity which were destroyed by the above brutal & ferocious invader who treated this people as an ignorant race, himself however not knowing a letter in the alphabet” (56). Here he is rearticulating a version of the Black Legend, a narrative which casts the practices of the Spanish Empire in the Americas in as negative light as possible. This version of history insists that Spanish imperialism exhibited a more violent and evil nature than the colonizing practices of other European powers. One payoff of Lamar’s introduction of this discourse into his journal is that it makes the modern processes of Native American removal seem like a humane venture when compared to the atrocities committed by Spain. The other result for the journal is that the Black Legend discourse initiates a rhetorical strain in which Lamar contrasts present day Mexico (an inheritor of Spanish power in North America) as an embodiment of tyranny against the U.S. as a representative of freedom. He makes this dichotomy most explicit when recounting a tribute to those who died in the 1832 Battle of Velasco, a conflict between Texas colonists and Mexico that anticipated the Texas Revolution: “Epitaph written for the Americans who fell at Velasco – ‘Who fought here fell in freedom’s cause – the Brave Tyrants beware! Man will not be a slave – ’” (see Figure 2). Lamar frames the growing Texas Revolution not as a fight against federalism or a struggle to maintain the institution of slavery – how most historians have since interpreted it – but rather as a righteous strike against despotism in the Americas.

Mexico’s disconnect from the principles of justice, according to Lamar, has resulted in a Texas territory that has fallen into lawlessness and violence. The resonance here with his description of the Comanche is purposeful, as he feels that neither they nor Mexico is worthy of controlling Texas and its bountiful resources. Lamar critiques the Mexican residents of Texas for their ignorance of the modern legal system when he writes, “Amongst other petitions this province laid in one for a system of Judicature more consistent with the education and habits of the american population which was readily granted, but the members of the Legislature, familiar with no system but their own were at a loss to devise one which would likely prove adequate to the wants and suited to the genius of the people” (77). Texas emerges in the journal, then, as a site in need of order and desperate for progress. While Mexico and the region’s Indians cannot provide these things, Lamar indicates that American settlers bring with them the promise of both peaceful stability and economic productivity. Ultimately, the place of Texas within the historiography of U.S. as empire is a complex one. After all, the U.S. itself was not directly involved in the Texas Revolution, though many of the revolutionaries hailed from the United States originally. However, its 1845 annexation to the U.S. shortly before the outbreak of the U.S.-Mexican War continued to involve Texas in the escalating tensions between the two countries. Lamar recognized the critiques that could be leveled against U.S. settlers and their actions in Texas, and much of his journal is designed to justify their behavior. Taking these histories into account, it would be worthwhile to compare some of the language found in Lamar’s travel journal with the rhetoric driving U.S. expansionism over the course of the nineteenth century.

Lamar’s involvement in the Texas Revolution, as glimpsed in this journal, already makes him an important figure in the burgeoning field of inter-American studies. His participation in the U.S.-Mexican war and the time he spends in Nicaragua further cement him as a person of great interest to those students and scholars who wish to use a hemispheric approach in the study of American history and culture. These latter two ventures also resulted in several poems, in which Lamar writes adoringly of beautiful local women. During his time as a soldier in Mexico, he produced “To a Mexican Girl” and “Carmelita,” while his ambassadorship to Nicaragua saw his writing of “The Belle of Nindiri” and “The Daughter of Mendoza,” all of which can be found in The Life and Poems of Mirabeau B. Lamar. Lamar’s travel journal will prove useful to literature and history classrooms alike that take inter-American studies as a point of interest. Moreover, it could play a central role in courses devoted to the history of Texas as well as to the history of U.S.-Mexican relations. Like any number of documents found in the ‘Our Americas’ Archive, Lamar’s journal ultimately invites us to forge connections across both geopolitical and disciplinary boundaries.

Bibliography

Graham, Philip, ed. The Life and Poems of Mirabeau B. Lamar. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 1938.

Kaplan, Amy and Donald Pease, eds. The Cultures of United States Imperialism. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1993.

Shcueller, Malini Johar. U.S. Orientalisms: Race, Nation, and Gender in Literature, 1790-1890. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan Press, 1998.

Siegel, Stanley. The Poet President of Texas: The Life of Mirabeau B. Lamar, President of the Republic of Texas. Austin, TX: Jenkins Publishing Co., 1977.

Streeby, Shelley. American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture. Berkeley: U of California Press, 2002.

Sundquist, Eric J. Empire and Slavery in American Literature, 1820-1865. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 2006.