The Experience of the Foreign in 19th-Century U.S. Travel Literature

The travel narrative emerged as one of the most popular, if not the most popular, literary genre among nineteenth-century U.S. readers. Several critics, including Justin Edwards in his Exotic Journeys: Exploring the Erotics of U.S. Travel Literature, 1840-1930, have speculated on the type of socio-cultural work performed by these writings. Edwards and others have observed the travel narrative as a meaningful blend of entertainment and education. Detailed accounts of journeys to locales outside of the nation’s boundaries fed the desire of readers for knowledge regarding the foreign and the exotic. Perceived differences in behavior, custom, and belief held a deep fascination for the nineteenth-century citizen, and, for many, the travel narrative provided the only vehicle for engaging that fascination. In addition to building a foundation of knowledge on foreign locales and populations, these narratives offered individual readers an opportunity to negotiate his/her position within the ever-shifting political landscape of the nation. With their authors/protagonists serving as a sort of proxy for those eager to experience their own encounter with the exotic, these writings encouraged their readers to think through their own national, racial, and gendered identities. The socializing function of the travel narrative, that which affirmed the place of its readers within the nation and subsequently the world, dovetailed nicely with the political project of Manifest Destiny and the westward expansion of the U.S. throughout the nineteenth century. Therefore, many of the most popular travel narratives, including Richard Henry Dana’s Two Years Before the Mast (1840) and Mark Twain’s Roughing It (1872), were those that centered around the western portions of what would eventually become the continental United States.

Reading George Dunham’s A Journey to Brazil (1853) - part of the ‘Our Americas’ Archive Partnership, a digital archive collaboration on the hemispheric Americas - alongside texts such as Two Years Before the Mast and Roughing It will prove to be a highly rewarding endeavor for students of nineteenth-century U.S. culture and literature. Dunham has compiled a detailed, if somewhat haphazard, travelogue of his voyage on board the ship Montpelier and then his protracted stay in mid-nineteenth-century Brazil. Brazilian plantation owners brought him over in order to help modernize their plantation system through his knowledge of and experience with advanced agricultural technologies as well as the efficient organization of slave labor. If writers such as Dana and Twain provide us with insights into the role played by culture in the processes of territorial expansion that characterized the nineteenth-century U.S., then what may we learn from more obscure travel writings on what may be more unexpected locales? Dunham’s journal (held at Rice University's Woodson Research Center) contains many of the same dynamics as those more studied travel narratives and will offer some useful points of comparison with those texts.

Similar to other works of the time, Dunham foregrounds the exoticism of the foreign that readers found so tantalizing. Arriving in Brazil for the first time, he marvels at the sense of difference he feels between this place and the U.S.: “I first sett (sic) foot on land in Bahia in Brazill (sic) and looked around in astonishment it seemed like being transported to another planet more than being on this continent everything was new and wonderfull (sic) the buildings without any chimneys and covered with tiles the streets narrow and full of negroes a jabbering” (35). He goes on to write, in a similar vein, “the trees green and covered with tropical fruit and every thing else so different from home that was some time before I could realize that I was here” (36). The combination of foreign landscape, architecture, and peoples overwhelms Dunham, producing in him a sense of disorientation that was common among nineteenth-century author-travelers. At the same time, the presence of a black slave population would have been a point of keen interest, as well as identification, for many U.S. readers. Dunham no doubt knew that readers would be projecting their own experiences with slavery onto these moments within his journal, exciting curiosity about his experiences and debate about the relative merits and practices of the slave system. Many critics, such as Amy Kaplan in The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.S. Culture, have written that it is this blurring of the domestic and the foreign, of home and abroad, that is central to the socio-cultural operations of travel literature.

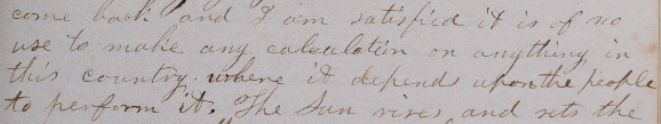

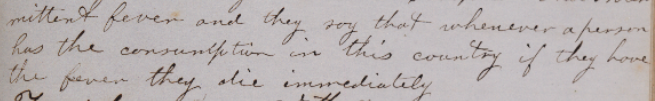

Later in the journal, after he has spent some time in Brazil, Dunham engages in sharp criticisms of the practical workings of this society, another familiar trope from the travel narrative. Manifestations of his frustration take on nationalist overtones in statements such as, “I am satisfied it is of no use to make any calculation on anything in this country where it depends upon the people to perform it” (see Figure 2 [a]); or, “they say that whenever a person has the consumption in this country if they have the fever they die immediately” (see Figure 2 [b]). The latter pronouncement portends the death of the American traveler owing to the relative medical backwardness of foreign lands. The implied superiority of U.S. knowledges and practices pervades much travel literature of this time, including those aforementioned texts concerning the burgeoning western frontier. As scholars have noted, these articulated attitudes toward the western territories invited, or perhaps even demanded, the civilizing influence emblematized by competent white Americans.

In designing a lesson plan around Journey to Brazil and nineteenth-century U.S. travel narratives, an instructor may also want to include a representative of those works dedicated to travel in the Holy Land. Texts that focused on journeys to Palestine and its surrounding territories enjoyed a massive degree of popularity among American readers, particularly in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Some of the more popular of these works included Twain’s The Innocents Abroad (1869) and W. M. Thomson’s The Land and the Book (1870), an illustrated travelogue of the Holy Land. In his critical study American Palestine: Melville, Twain, and the Holy Land Mania, Hilton Obenzinger argues that since many Americans regarded themselves as a chosen people, anointed by God to carry out a revivalist mission in this new nation, written works on the Holy Land held for them a special interest. Obenzinger insists, and many critics agree with him, that even if Holy Land literature was not the most popular form of travel narrative (though it may have been), then it was certainly the most ideologically significant. Dunham’s journal forces us to at least re-think that assertion. The 1853 publication of the journal shows an interest on the part of the American reading public in travel, both real and imagined, to places throughout the Americas as well. Richard Henry Dana, the same man who famously wrote on the western frontier, would chronicle his travels in the Caribbean in an 1859 book entitled To Cuba and Back: A Vacation Voyage. John O’Sullivan, accredited with the coining of the term “Manifest Destiny,” would in later years become a staunch advocate for the annexation of Cuba to the U.S. Finally, A Journey to Brazil provides yet another piece of compelling evidence that the hemisphere as a whole played a role in the U.S. imagination equal to that of both the western frontier and the Holy Land.

Bibliography

Dana, Richard Henry. Two Years Before the Mast and Other Voyages. New York: Library of America, 2005.

Edwards, Justin. Exotic Journeys: Exploring the Erotics of U.S. Travel Literature, 1849-1930. Hanover, NH: UP of New England, 2001.

Kaplan, Amy. The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.S. Culture. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2002.

Obenzinger, Hilton. American Palestine: Melville, Twain, and the Holy Land Mania. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1999.

Thomson, W. M. The Land and the Book. London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1870.

Twain, Mark. The Innocents Abroad; Roughing It. New York: Library of America, 1984.