Antebellum U.S. Migration and Communication

The nineteenth century in the United States was a period of movement. A wave of migration in the 1830s and 1840s witnessed easterners heading out from established states into unsettled territories and challenging new environments across the West and Southwest. These migratory adventures slowed significantly during the late 1850s, 1860s, and early 1870s, as individuals were drawn into the Civil War and its aftermath. However, by the 1880s, many people were on the move again, often trying to get to the west coast and finding themselves stranded in mid-America. Despite the military and social conflicts of the 1830s and 1840s, Texas, or the land that would become Texas, became a popular settlement point for migrants from a wide variety of backgrounds and with an equally diverse set of goals. Two letters and a travel diary, available online as part of the ‘Our Americas’ Archive Partnership (a digital collaboration on the hemispheric Americas) and physically housed in Rice University’s Woodson Research Center, can assist in teaching exercises focused upon the movement of peoples and ideas in the antebellum U.S.

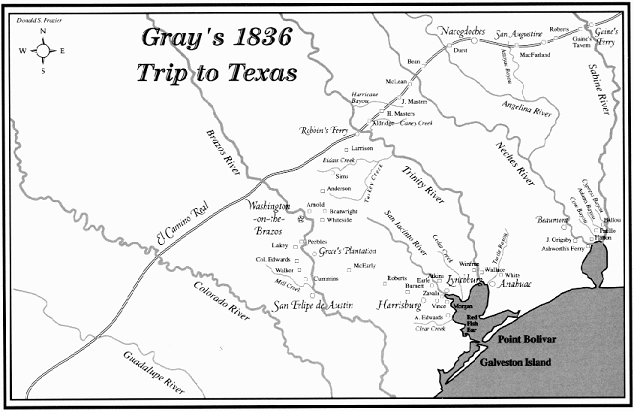

As it is critical to understand geography when discussing travel movements, to facilitate the lesson an educator could project onto a screen a map of the United States, so that students can visualize the actual movements of the individuals in question. The class can be organized around a series of questions: why did people migrate? how did they perform these migrations (logistics)? what challenges did they face during travel? how did all of these individuals keep in contact as the nation expanded? An educator can start the conversation by asking students why people migrate today, perhaps providing an overview of push/pull factors. For example, in his diary, Colonel William Fairfax Gray describes how the financial panics of the 1830s resulted in many financially ‘broken’ people packing up and heading to Texas to start over financially. As Gray states, “Texas just then loomed up as a land of promise…” For a general overview of these movements, with a Texas focus, see Randolph Campbell’s Gone to Texas: A History of the Lone Star State (2003). It is also critical to stress that these choices to migrate were often laden with conflict, as certain family members would resist the move for a variety of reasons. To understand these disagreements it might be useful to assign segments of the diaries of women provided within Joan Cashin’s A Family Venture: Men and Women on the Southern Frontier (1991).

The migration process itself was quite often difficult and dangerous in nature, regardless of prior preparations. At this point, ask students to go through Gray’s diary making a list of the challenges that he faced during his travel period. This exercise will result in a lively conversation as Gray recalls everything from intoxicated coach passengers to seductive widows. Sickness and injury resulted in a constant parade of interesting figures before Gray. On Oct. 11, 1835, he wrote, “here I am, at the end of my journey (that is, across Virginia), without one of the companions that I set out with! What a picture of the way-fare of human life!” Although Gray travelled on his own, his diary allows for an introduction into a current debate amongst historians. The debate focuses on the degree to which family and kin connections mattered with regards to migrations. Namely, is the solo adventurer model true or was it more common for extended family lines to make the trek? For lecture material on this subject see Carolyn Earle Billingsley’s Communities of Kinship (2004), which makes an argument for kin-centered migration. Educators can also return to the map at this point and ask students to trace the movements of Gray by using the clues contained within his diary. This will impress upon students the fact that travel took much longer during this period then it does today.

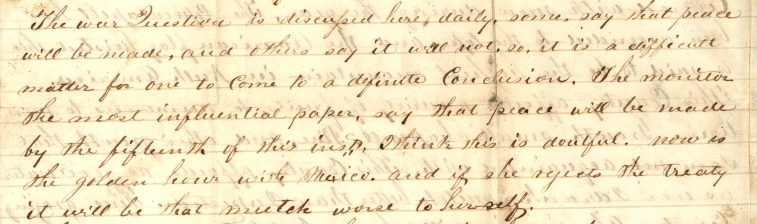

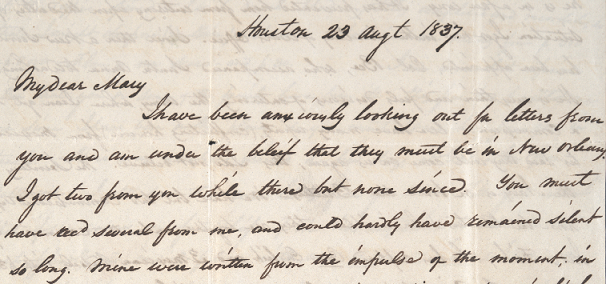

It can also be stressed that communication happened at a slow pace, especially as compared to our modern computer age. In the antebellum period, letters were one of the principal methods of communication and, in fact, letter writing evolved into an art form. It might be revealing to ask students how many letters they have written in their lifetime. Then, ask them to look at two letters: one 1848 letter by M. Mattock from Molina Del Rey, Mexico, and another 1837 letter from Moreau Forrest in Houston, Texas. How is news conveyed within these letters? Mattock describes how the “war Question” is discussed daily at his location while Forrest (over ten years earlier) also mentions that an impending war with Mexico is a possibility. Forrest, in particular, laments the sluggish pace of the mail service and he writes a relative, “I have been anxiously looking out for letters from you and am under the belief that they must be in New Orleans. I got two from you while there but none since. You must have had several from me…” At this juncture you could request students to write a letter to a family member describing their day, using similar language and formatting as these early letters. Or, you could have them model a letter off of a diary entry/day in the life of William Gray. These exercises will help students to grasp the history of the period while also comprehending what it felt like to be an antebellum traveler.

Bibliography

Billingsley, Carolyn Earle. Communities of Kinship: Antebellum Families and the Settlement of the Cotton Frontier. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004.

Campbell, Randolph B. Gone to Texas: A History of the Lone Star State. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Carroll, Mark M. Homesteads Ungovernable: Families, Sex, Race, and the Law in Frontier Texas, 1823-1860. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001.

Cashin, Joan E. A Family Venture: Men and Women on the Southern Frontier. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Lack, Paul D. The Texas Revolutionary Experience: A Political and Social History, 1835-1836. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1992.

Winders, Richard Bruce. Crisis in the Southwest: The United States, Mexico, and the Struggle over Texas. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources, 2002.