Chapter 4. Personal Narratives and Transatlantic Contexts during the U.S.-Mexican War

“I LEFT home for the United States in the summer of 1845, for the same reason that yearly sends so many thousands there, want of employment,” writes Scottish immigrant and English soldier George Ballentine. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the U.S. received into its midst waves of immigrants from across the globe. Immigrant experiences like Ballentine’s were often related and recorded through the form of personal narrative and autobiography. Within these narratives, many immigrants continue to reference conditions in their homeland, creating a comparative structure that relates to transatlantic, trans-pacific, and hemispheric histories of circulation and migration. Ballentine’s immigrant experience was a specifically transatlantic experience which adopted hemispheric implications as a result of his travels throughout the U.S. Mexican borderlands. His Autobiography of an English Soldier offers a key way through which to highlight his history of immigration and introduce students to an important literary form: the personal narrative.

Teachers can begin by introducing Ballentine’s narrative as an example of a multilayered personal narrative that represents genres of autobiography and immigration. Personal narrative, as Jonathan Arac argues in The Emergence of American Literary Narrative, 1820-1860, is founded upon displacement – pacific voyages, overland journeys to the frontier, slaves’ escapes, or immigrant, Atlantic journeys like Ballentine’s (76); however, this displacement is not only physical. It also occurs in the relationship between author and reader. Readers are urged to know the narrator, while realizing that there is a difference between the world in which they live and the world in which the narrator lived historically. More specifically, this difference pertains to how the narrative functions as a representation of historical experience and how the reader experiences that narrative as they read it (Arac 76). This distinction provides a key moment for teachers to help students learn about the internal world of a text. What do certain words, phrases, and experiences mean within Ballentine’s narrative? What do they mean in terms of the historical context, and what do they mean to us today? By showing students this process of translation, they can learn the complex layers through which literary narratives convey meaning.

As a part of the early American literary tradition, Ballentine’s narrative joins a long line of 19th century autobiographical and first-person narratives, such as the Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (1771-1790), Richard Henry Dana's Two Years Before the Mast(1840), the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), and Henry David Thoreau's Walden (1854).Personal narratives typically have the “circular shape of descent and return,” meaning characters often fall by way of some experience and return to a state of ordinary, civilized life (Arac 77). These narratives function as a way to see another form of life and travel into the past. In addition, Ballentine’s narrative can be located within studies of first-person immigrant texts, such as John Hector St. John de Crèvecœur’s Letters from an American Farmer (1782) (an electronic version linked in the OAAP via the Early Americas Digital Archive), Mary Antin’s The Promised Land (1912), and many more. Frequently, personal narratives are appropriated into national narratives; they are used to understand the nation within a certain space and time (77). Teachers might consider pairing Ballentine's autobiography with one of these canonical American literary narratives, helping students to see the similarities and differences within the genre of personal narrative. For instance, teachers might have students read the first five pages of Ballentine's narrative and the first five pages of Benjamin Franklin's narrative to show the different ways in which authors introduce themselves and their writing. What are the first pieces of information that these authors reveal about themselves? What reasons do they provide for writing their narratives? Such questions can help students understand the formula of personal narratives and how various authors deviate from it.

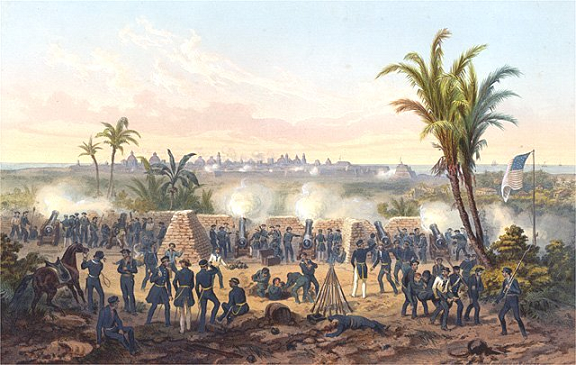

Autobiography of an English Solider begins with a classic immigrant arrival story into the harsh streets of New York, where Ballentine quickly realizes that he is “scarcely prepared to find the scramble for the means of living so fierce and incessant, as I found it in New York” (9). Although he attempts to first find employment as a weaver or a whaler, he eventually decides to continue his occupation as a soldier and enlist in the American army. Traveling from Fort Adams, Rhode Island to Pensacola, Florida to Tampico, Mexico, Ballentine eventually participates and observes the siege of Veracruz, which led to the inland march toward Jalapa during the U.S.-Mexican War (1846-1848). Ballentine’s personal narrative situates his experience in the U.S.-Mexican War as part of his immigration experience, and provides a geographic outline of the U.S. during the war as well as a sense of U.S. politics. Furthermore it calls us to understand his first person narrative as one told and interpreted by a witness. By highlighting that his narrative is both a primary historical source and a literary form using conventions and narrative structures, teachers can help students to understand both the historical and literary nature of the personal narrative. What type of language does Ballentine use? How does he describe the battles? What features of his descriptions point to a first person experience?

For a more specific example, teachers might draw students’ attention to the historical details surrounding Ballentine’s retelling of the war. His descriptions provide a first-hand account of the siege of Veracruz, and a defense of General Winfield Scott, who received considerable criticism for his fierce bombardment of Veracruz (152). Teachers might have students research Scott and the criticism surrounding his leadership in this battle. In so doing, teachers can remind students that personal narratives, like all narratives to a certain extent, endorse a certain point of view. What is Ballentine’s point of view? Can we discern his political understanding of the war? What does his narrative tell us about U.S. relations with Mexico? Does he seem like a reliable narrator? Such questions can help students to think critically about what they read, how they read it, and the role of the narrator. For instance, Ballentine compares the poor treatment of the American soldiers to his former experience in the British army. He writes in reference to the soldiers transportation aboard a ship, “In the American, service by the bye, soldiers always lie on the boards when on board ship; in the British service, where the health and comfort of a soldier are objects of study and solicitude, a different custom prevails; a clean blanket and mattress being issued to the soldier on his going on board”(89). Like many immigrant novels, Ballentine’s former homeland stands as a place of comparison. How does his British origin influence his narration of the U.S. and the U.S. Mexican War? Studying the relationship between Ballentine’s homeland (Scotland/Britain) and the U.S. can help students to understand how his perspective of the war was primarily developed outside of the U.S. How is this personal narrative representative of Ballentine’s transatlantic crossing? How is it also representative of borderlands and hemispheric narrative?

Teachers can also highlight Ballentine’s British-American perspective by calling attention to his use of literary references and conventions. For instance, his description of the siege of Veracruz recreates and relies on the sounds of battle, employing a literary allusion and generic convention to enhance his retelling of the event. Stationed at a small village four miles from Veracruz, he hears the terrifying sound of a canon shell whizzing past him. He writes:

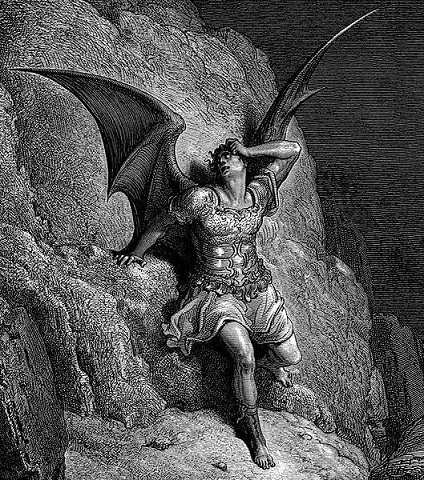

There is no earthly sound bearing the slightest resemblance to its monstrous dissonance; the angriest shriek of the railway whistle, or the most emphatic demonstration of an asthmatic engine at starting of a train, would seem like a strain of heavenly melody by comparison. Perhaps Milton's description of the harsh, thunder-grating of the hinges of the infernal gates, approaches to a faint realization of the indescribable sound, which bears a more intimate relation to the sublime than the beautiful. (155)

This description of battle offers a key way for teachers to introduce literary concepts into what appears a straightforward autobiography. The “sublime,” a key concept of British Romanticism and, later, American Romantic literature, was originally used to describe feelings of awe and wonder often inspired by the natural world. Here, Ballentine uses it to describe the sounds of war, throwing in a reference to John Milton’s portrait of hell to dramatize his own terror and the unnerving sounds of battle. What does he compare his experiences to? How does his reference to Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) formulate meaning within the text? What does it mean to locate a 17th century British poet within a story of the 19th century U.S.–Mexican War? This reference provides a key opportunity to define the literary term “allusion.” An allusion is: “a reference in a literary work to a person, place, or thing in history or another work of literature” (All American:Glossary of Literary Terms).

These types of questions can help students to do the investigative work of literary analysis by urging them to find the references and conventions that configure meaning. In fact, Ballentine makes multiple literary references throughout his autobiography. For instance, he makes allusions to Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" (1798), Frederick Marryat's lesser-known novel Snarleyyow (1837), and Augustus Jacob Crandolph's gothic novel The Mysterious Hand; or, Subterranean Horrours! (1811). Interestingly, these cultural references situate the literature of the British Romantics within the context of the Mexican-American War, allowing these texts to produce new meaning. Furthermore, many of these allusions refer to stories of the sea, and Ballentine's brief experience of travel along the Atlantic and Gulf coastlines. For an exercise, teachers might have their students read a section of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and consider how Ballentine’s allusion works within the text. What can we learn from this type of reference? Is it helpful in understanding Ballentine’s experience? What new meaning does it add to Coleridge’s well-known poem? Although many of Ballentine’s references are allusions to British literature, they would not have escaped many of his contemporary American readers. Moreover, he also references American texts, such as Herman Melville’s 1851 American epic, Moby Dick. His use of both British and American literary references reveals the blending of literary cultures and histories and locates them within a story of shifting national borders.

After presenting a lesson on personal narratives, teachers might present students with the following questions:

What is a personal narrative? How does it function? Provide an example.

What influences Ballentine’s perspective in his autobiography?

What can we learn about the U.S. and the U.S.-Mexican War from Ballentine’s narrative?

What is a literary allusion? Do you think it is important or helpful to research historical references and/or literary allusions? Why or why not? (This is an opinion question).

Write your own one page personal narrative. Choose an event from your life and retell the story from your perspective.

Bibliography:

"All American: Glossary of Literary Terms." University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Accessed July 2011. All American:Glossary of Literary Terms.

Arac, Jonathan. The Emergence of American Literary Narrative, 1820-1860. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2005.