Toy Theatres and Puppet Shows for Children

WHETHER, out of their infinite variety, the puppets please or fail to satisfy us, there is one audience invariably eager for them. Puppet shows for children, toy theatres managed by children, what could be more fitting? Specially adapted, professional performances such as the Guignol and Casperle plays have ever catered to youthful tastes with astonishing and perennial success. The home-made booths for simple dolls worked on the fingers are so quickly contrived. Little stages for marionettes are easy to construct out of ordinary kitchen tables. Mr. Gordon Craig gives explicit directions as well as an excellent drawing in his letter, The Game of Marionettes, which is published in The Mask, volume five. Shadow plays can be arranged by merely stretching a sheet across a door with a cardboard frame and cardboard figures pressed behind it and a light to illuminate the silhouettes. How much fun to have Red Riding Hood thus portrayed, for a birthday party or the shadow of Santa Claus with his reindeer sailing over the shadow gables and down the shadow of the chimney on Christmas eve!

The Juvenile Drama of Skelt and his successors, Park, Webb, Redington and Pollock, has been immortalized by Stevenson in his little essay, A Penny Plain and Twopence Colored. Printed on thin sheets of cardboard to be cut out and colored by the youthful stage manager (unless he bought, oh shame! the Twopence Colored), were characters and scenes for the most exciting plays. Special properties for illuminating and coloring could be acquired also, at extra expense. The words of the drama, plus directions, were printed in a pamphlet. They were based upon thrilling old English melodramas; they presented startling and highly theatrical situations.

“In the Leith Walk window all the year round, there stood displayed a theatre in working order, with a Forest Set, a Combat, and a few Robbers Carousing in the slides; and below and about, dearer tenfold to me! the plays themselves, those budgets of romance, lay tumbled one upon the other. Long and often have I lingered there with empty pockets. One figure, we shall say, was visible in the first plate of characters, bearded, pistol in hand, or drawing to his ear the clothyard arrow. I would spell the name: was it Macaire or Long Tom Coffin, or Grindoff, 2d dress? Oh, how I would long to see the rest! How—if the name by chance were hidden—I would wonder in what play he figured and what immortal legend justified his attitude and strange apparel! And then to go within to announce yourself as an intending purchaser, and, closely watched, be suffered to undo those bundles and to breathlessly devour those pages of gesticulating villains, epileptic combats, bosky forests, palaces and warships, frowning fortresses and prison vaults—it was a giddy joy.”

“And when at length the deed was done, the play selected and the impatient shopman had brushed the rest into the gray portfolio, and the boy was forth again, a little late for dinner, the lamps springing into light in the blue winter’s even, and The Miller, or The Rover, or some kindred drama clutched against his side, on what gay feet he ran, and how he laughed aloud in exultation!” And Stevenson confesses: “I have, at different times, possessed Aladdin, The Red Rover, The Blind Boy, The Old Oak Chest, The Wood Daemon, Jack Shepard, The Miller and His Men, Der Freischuetz, The Smuggler, The Forest of Bondy, Robin Hood, The Waterman, Richard I., My Poll and my Partner Joe, The Inchcape Bell (imperfect), and Three-fingered Jack the Terror of Jamaica; and I have assisted others in the illumination of the Maid of the Inn and The Battle of Waterloo. In this roll-call of stirring names you read the evidences of a happy childhood.”8

In Germany, also, toy theaters abound, better equipped possibly, and more carefully constructed, but lacking somewhat the quaint and fiery delightfulness of the English juvenile drama.

There could be no more spontaneous testimonial of the love of children for the puppets than the throngs who crowded into Papa Schmidt’s Kasperle theatre to witness his familiar, jolly little shows of fairy-tale and folklore. In striving to meet the tastes and needs of children, Schmidt earned the reward of becoming the best beloved man in the city. It is interesting to note that when, once, he became discouraged and wished to retire, the city magistrates, urged by the superintendent of the schools, unanimously voted to build him a permanent little theatre.

And Goethe, that German genius of most universal appeal, records that he devoted many hours of his childhood to puppet play. Kept at home during the dreary days of the Seven Years’ War when Frankfurt was occupied by the French, he diverted not only himself but his family with the little marionette theatre which he had received as a Christmas gift. It is thus that he describes his introduction to the puppets who were to delight his boyhood, to amuse his youth and to inspire him eventually with the suggestion for his great Faust drama.

“I can still see the moment—how wonderful it seemed—when, after the usual Christmas presents, we were told to sit down before a door which led from one room into another. It opened, but not merely for the usual passing in and out; the entrance was filled with an unexpected festiveness. A portal reared itself into the heights which was covered by a mystic curtain. At first we marvelled from a distance and as our curiosity became greater to see what glittering and rustling things might be concealed behind the half-transparent drapery, a little chair was assigned to each of us and we were told to wait in patience.

“So then we all sat down and were quiet. A whistle gave signal, the curtain rose and disclosed a scene in the Temple, painted bright red. The High Priest Samuel appeared with Jonathan, and their curious dialogue seemed most admirable to me. Shortly thereafter Saul came upon the scene in great distress, over the insolence of the heavy-weight warrior who had challenged him and his followers to combat. How relieved I was when the diminutive son of Jesse sprang forth with shepherd’s crook, wallet and sling and spoke thus: ‘Almighty King and great Lord! Let none despair because of this. If your Majesty will permit me, I will go forth and enter into combat with the mighty giant.’ The first act was ended and the audience extremely desirous to learn what would happen next,” etc., etc.

GERMAN PUPPET SHOW FOR CHILDREN

Designed for use in the home

[Reproduced from Kind und Kunst]

The puppets may indeed boast of having delighted child geniuses of every country and of having inspired their later years. We are told that at the age of eleven Stanislaw Wyspianski, the great poet, painter and dramatist of Poland, built himself a large stage or Crib imitating architecturally the Castle of Wawel. On this stage he produced various dramas based upon the history of that royal burg, with the help of figures which he himself invented. “Perhaps,” his biographer suggests, “already there was germinating in his boyish soul the idea of the Theatre-Wawel which in his manly productiveness brought forth manifold fruits.” (L. de Schildenfeld Schiller.) In Italy, too, we find the great dramatist Goldoni devoted to puppet play as a child and writing dramas for the burattini which he is said to have adapted later, with great success, for the larger stage.

Most famous, perhaps, of all popular puppets for children to-day are the Guignols in Paris. A typical performance might be found in the garden of the Luxembourg, where a little stage has been erected. One has the privilege of standing outside the roped-off space with passing pastry cooks, milliners’ girls and street urchins, or one may pay to enter and sit down on a chair among the children and nurses. Coachmen rein up and watch from their high perches at the curb. Polichinelle first comes upon the stage with his piping voice, or the Director, a doll in evening dress with waxed mustachios, welcomes the audience. Then Guignol and the terrifying family scenes!

Mr. W. Caine has given a very illuminating analysis of the guignols. “But who are all these people? Guignol, Guillaume, the Judge, the Patron, the Nurse? You might know that Guignol is Guillaume’s father, while Guillaume is the son of Guignol. The Gendarme, on the other hand, is the Gendarme, while the Judge, similarly, is the Judge. The Patron is none other than the Patron, and who should the Nurse be, in the name of common sense, but the Nurse? The Gendarme is always killed, always. The Judge expends his wrath impotently, always. The Patron is invariably worsted, the Nurse has no sort of luck. Guignol represents the proletariat. He wears a dark green jacket and a black hat.... His face is large and foolish, for he is what is known as a benet, a simpleton.... He tries to give his own baby its dinner by thrusting it head-first into a stewing pan. Guillaume wears a red hat and pink blouse.... Guillaume is, in one word, a rascal. It is certain when once Guillaume gets hold of a stick, or musket, or a stewing-pan (anything will do) that somebody will bite the dust.”

The enthusiasm of the juvenile audience grows most intense over the exploits of this favorite, and it is not unusual when Guillaume is sore put to it and the Gendarme is about to pounce upon him, to hear a shrill little voice from the audience cry out, ‘Take care, Guillaume, the Gendarme is behind the door!’ When for the first time the adventurous Guillaume ascended in an aeroplane, so great was his success that the price of seats in the Champs Élysées went from 10 centimes to 25!!”

Guignol is often to be found during the season at bathing resorts and at the seashore. Each of the larger shows in Paris has a portable booth belonging to it wherein its little cast can be sent out to perform at private entertainments. It is not uncommon for the play to be sent to the orphans and waifs in this manner as a special treat for fête days.

We find the puppets equally beloved by the children of Italy. In The Marionette there is a sympathetic picture of a juvenile audience at the theatre of the Lupi family in Torina. “On the evenings of ordinary days the auditorium does not differ in aspect from that of the other theatres. To see it in its especial beauty one must go to the Sunday afternoon performance, when hundreds of boys and girls fill the seats and benches, and form, in the platea and the boxes, so many bouquets, garlands of blond heads; and the variety of light bright colors of their clothes give it the appearance of a sala decked with flowers and flags for a fête.

“On the rising of the curtain one may say that two performances begin. It is delightful, during a spectacular scene, to see all those eyes wide open as at an apparition from another world—those expressions of the most supreme amazement, in which life seems suspended—those little mouths open in the form of an O, or of rings and semicircles—those little foreheads corrugated as if in a tremendous effort of philosophic cogitation, which then relax brusquely as on awaking from a dream. Then, all at once, at a comic scene, at a funny reply or action of one of the characters, whole rows of little bodies double up with laughter, lines of heads are thrown back, shaking masses of curls, disclosing little white necks, opening mouths, like little red caskets full of minute pearls; and in the impetus of their delight some embrace their brother or sister, some throw themselves in their mother’s arms, and many of the smallest fling themselves back in their seats with their legs in the air, innocently disclosing their most secret lingerie. And then, to see how in the passion of admiration they furiously push aside the importunate handkerchief which seeks their little noses, or deal a blow without preface to whoever hides from them the view of the stage! There are three hundred pairs of hands that applaud with all their might, and that, among them all, do not make as much noise as four men’s hands; one seems to see and to hear the flutter of hundreds of rosy wings, held by so many threads to the seats.

“And the admiring and enthusiastic exclamations are a joy to hear. At the unexpected opening of certain scenes, at the appearance of certain lambs or little donkeys or pigs that seem alive, there are outbursts of ‘Oh!’ and long murmurs of wonder, behind which comes almost always some solitary exclamation of a little voice which resounds in the silence like a sigh in a church, and ... ‘Ah, com’e bello!’ ... that breaks from the depths of the soul, that expresses fulness of content, a celestial beatitude.”

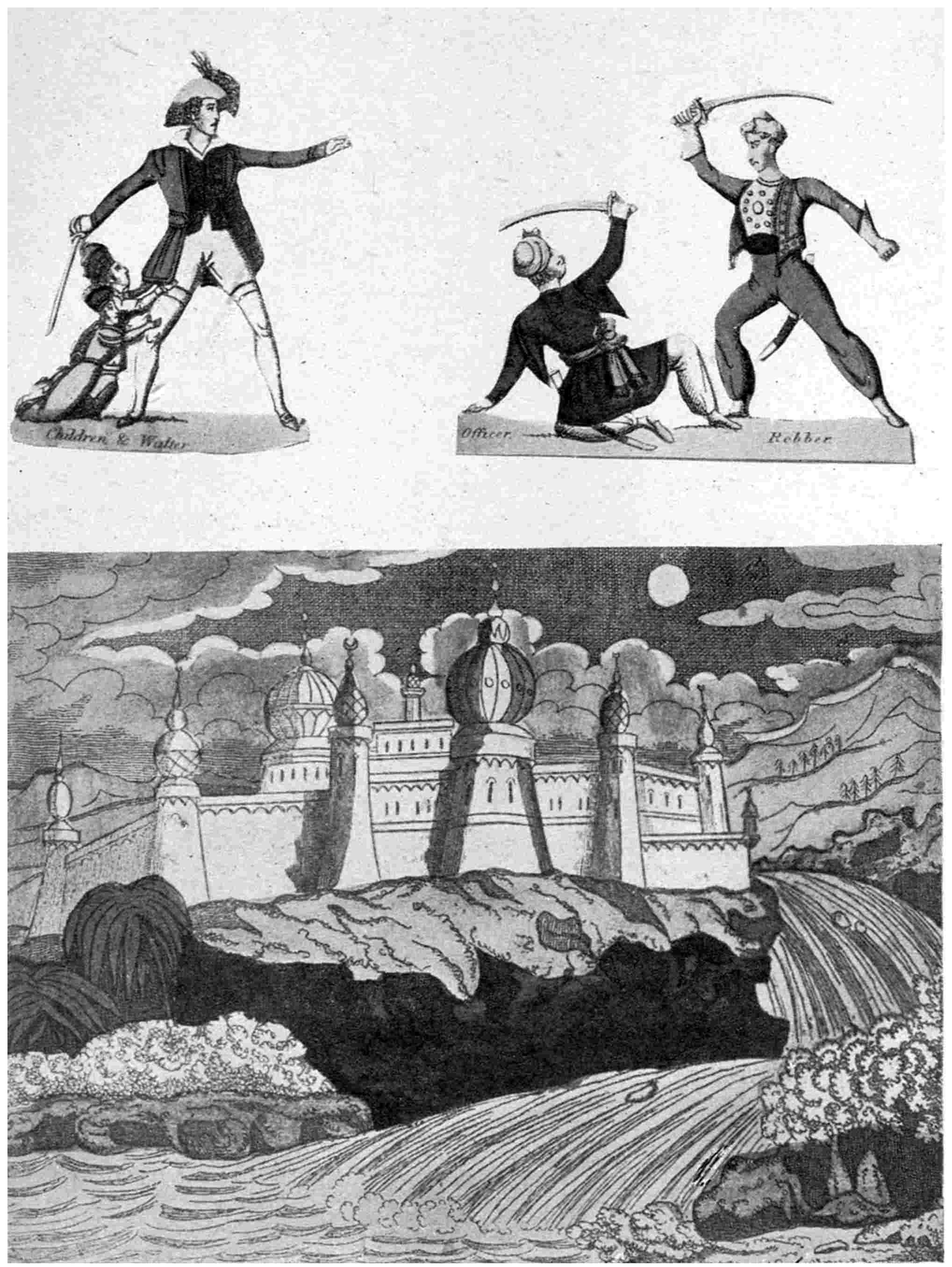

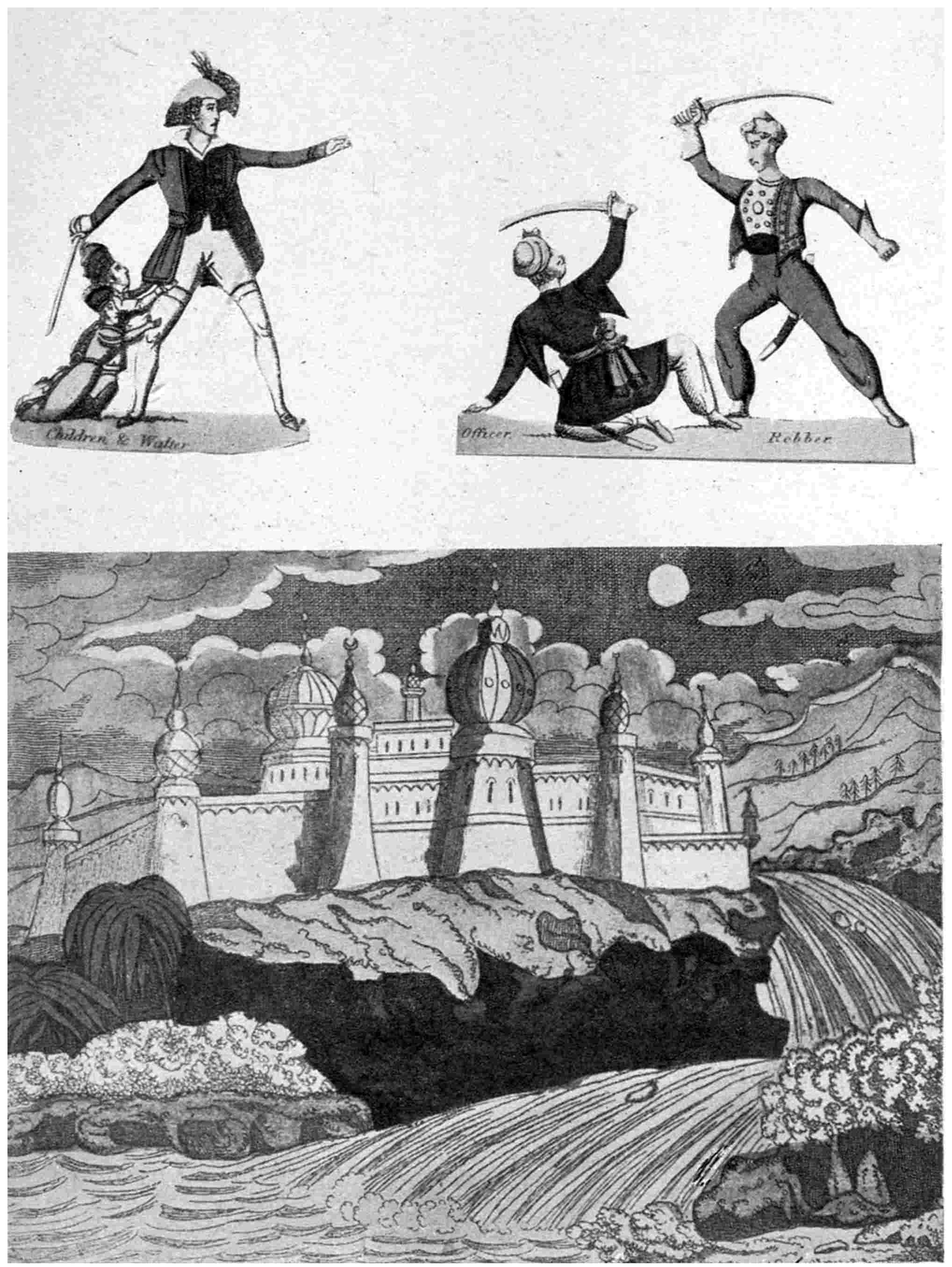

ENGLISH TOY THEATRE

Upper: Figures to be cut out for the Juvenile Dramas

Lower: Back scene for Timour the Tartar

[Courtesy of B. Pollock, 73 Hoxton Street, London]

When Mr. Tony Sarg brought The Rose and The Ring west it was a rare privilege for the children of Cleveland to see this winsome puppet play and an equal pleasure for those elders who witnessed the performance with them. What was behind the little curtain? A few boys and girls went tiptoe up to peek. Then, listen! there is music and then, oh! the funny little man singing a song, and oh! the long-nosed little King snoring on his throne, and the funny soldier, Hedsoff, saluting so briskly, and the ugly old Lady Gruffanuff! And see the Fairy Blackstick come floating in and do things and say things to people and Princess Angelica playing piano and dancing. How can she, so little and only a dolly? What a fat Prince Bulbo and oh, the armoured men on horseback fighting! (“Why ha’ dey dose knives, Mudda?” questioned one little girl, aloud, all unacquainted with the days of Chivalry). And then the roaring Lion! My four-year-old daughter still calls the lion a bear: but it pleased her notwithstanding, particularly the roar of it. “Oh, I just juve Mr. Sarg’s ma-inette dolls, Mudda,” she exclaimed, a day after the blissful event. “Why don’t we have ma-inette dolls many times?” Why indeed, or, why not?!

Elnora Whitman Curtis, in her book The Dramatic Instinct in Education, emphasizes the educational value of puppets. She would have shows in the schools, or better yet, in playgrounds with the advantage of fresh air. Subjects, she claims, could be vivified, literature and history lessons more deeply impressed upon the great number of pupils who never get beyond the grades. And for older children there would be the training in the writing of dialogues, in the declaiming of them, practice in fashioning the puppets, the costumes, the scenery, the properties and in operating and directing. Miss Curtis concludes: “Anyone who has watched a throng of small boys and girls as they sit in the tiny, roped-off square before a little chatelet in Paris on the Champs Élysées, or those that gather in Papa Schmidt’s exquisite little theatre in Munich, or before the tiny booths at fairs and exhibitions anywhere in Italy, must have noticed the rapturous delight of these small people. The tiny stage, its equipment, accessories, the diminutive garments and belongings of the puppets satisfy the childish love of the miniature copies of things in the grown-up world. Their animistic tendencies make it easy to endow the wooden figures with human qualities and bring them into close rapport with their own world of fancy. The voice coming from some unknown region adds the mystery which children dearly love, and before the magic of fairy-tales their eyes grow wide with wonder. The stiff movement of the puppets, their sudden collapses from dignity, are irresistibly funny to the little people and the element of buffoonery is doubly comical in its mechanical presentation.”

Less specifically, but with equal conviction of their deep educational importance, Gordon Craig proclaims: “There is one way in which to assist the world to become young again. It is to allow the young mind to learn nearly all things from the marionette.”