The Marionettes in America

“They come from far away. They have been the joy of innumerable generations which preceded our own; they have gained, with our direct ancestors, many brilliant successes; they have made them laugh but they have also made them think; they have had eminent protectors; for them celebrated authors have written. At all times they have enjoyed a liberty of manners and language which has rendered them dear to the people for whom they were made.”

ERNEST MAINDRON

HOW old are the marionettes in America? How old indeed! Older than the white races which now inhabit the continent, ancient as the ancient ceremonials of the dispossessed native Indians, more indigenous to the soil than we who prate of them,—such are the first American marionettes!

Dramatic ceremonials among the Indians are numerous, even at the present time. Each tribe has its peculiar, individual rites, performed, as a rule, by members of the tribe dressed in prescribed, symbolic costumes and wearing often a conventionalized mask. Occasionally, however, articulated figures take part in these performances along with the human participants. Dr. Jesse Walter Fewkes has published a minute description of a theatrical performance at Walpi which he witnessed in 1900, together with pictures of the weird and curious snake effigies employed in it.

The Great Serpent drama of the Hopi Indians, called Palü lakonti, occurs annually in the March moon. It is an elaborate festival, the paraphernalia for which are repaired or manufactured anew for days preceding the event. There are about six acts and while one of them is being performed in one room, simultaneously shows are being enacted in the other eight kivas on the East Mesa. The six sets of actors pass from one room to another, in all of which spectators await their coming. Thus, upon one night each performance was given nine times and was witnessed by approximately five hundred people. The drama lasts from nine P.M. until midnight.

Dr. Fewkes gives us the following description of the first act: “A voice was heard at the hatchway, as if some one were hooting outside, and a moment later a ball of meal, thrown into the room from without, landed on the floor by the fireplace. This was a signal that the first group of actors had arrived, and to this announcement the fire tenders responded, ‘Yunya ai,’ ‘Come in,’ an invitation which was repeated by several of the spectators. After considerable hesitation on the part of the visitors, and renewed cries to enter from those in the room, there was a movement above, and the hatchway was darkened by the form of a man descending. The fire tenders arose, and held their blankets about the fire to darken the room. Immediately there came down the ladder a procession of masked men bearing long poles upon which was rolled a cloth screen, while under their blankets certain objects were concealed. Filing to the unoccupied end of the kiva, they rapidly set up the objects they bore. When they were ready a signal was given, and the fire tenders, dropping their blankets, resumed their seats by the fireplace. On the floor before our astonished eyes we saw a miniature field of corn, made of small clay pedestals out of which projected corn sprouts a few inches high. Behind this field of corn hung a decorated cloth screen reaching from one wall of the room to the other and from the floor almost to the rafters. On this screen were painted many strange devices, among which were pictures of human beings, male and female, and of birds, symbols of rain-clouds, lightning, and falling rain. Prominent among the symbols was a row of six circular disks the borders of which were made of plaited corn husks, while the enclosed field of each was decorated with a symbolic picture of the sun. Men wearing grotesque masks and ceremonial kilts stood on each side of this screen.

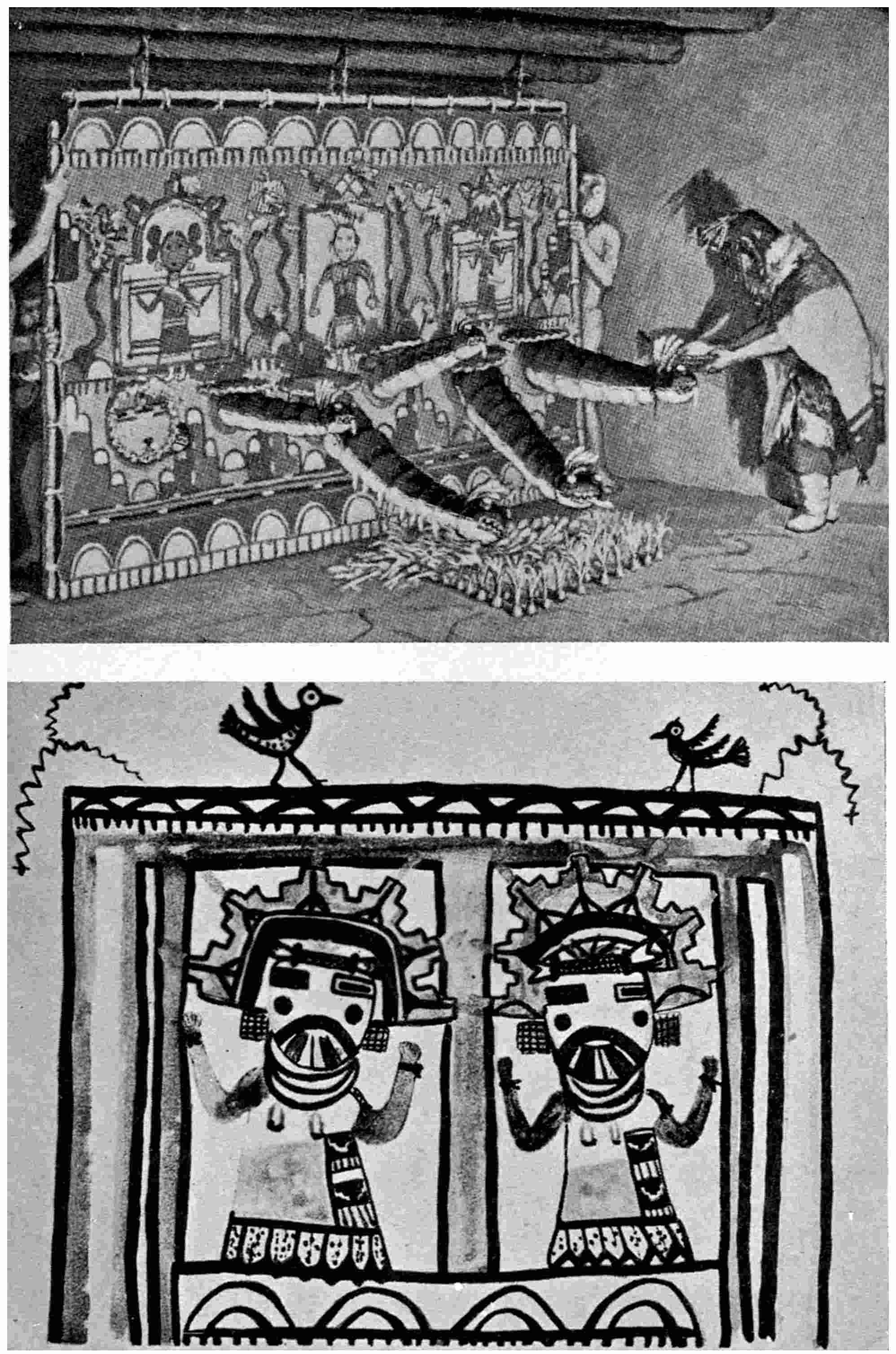

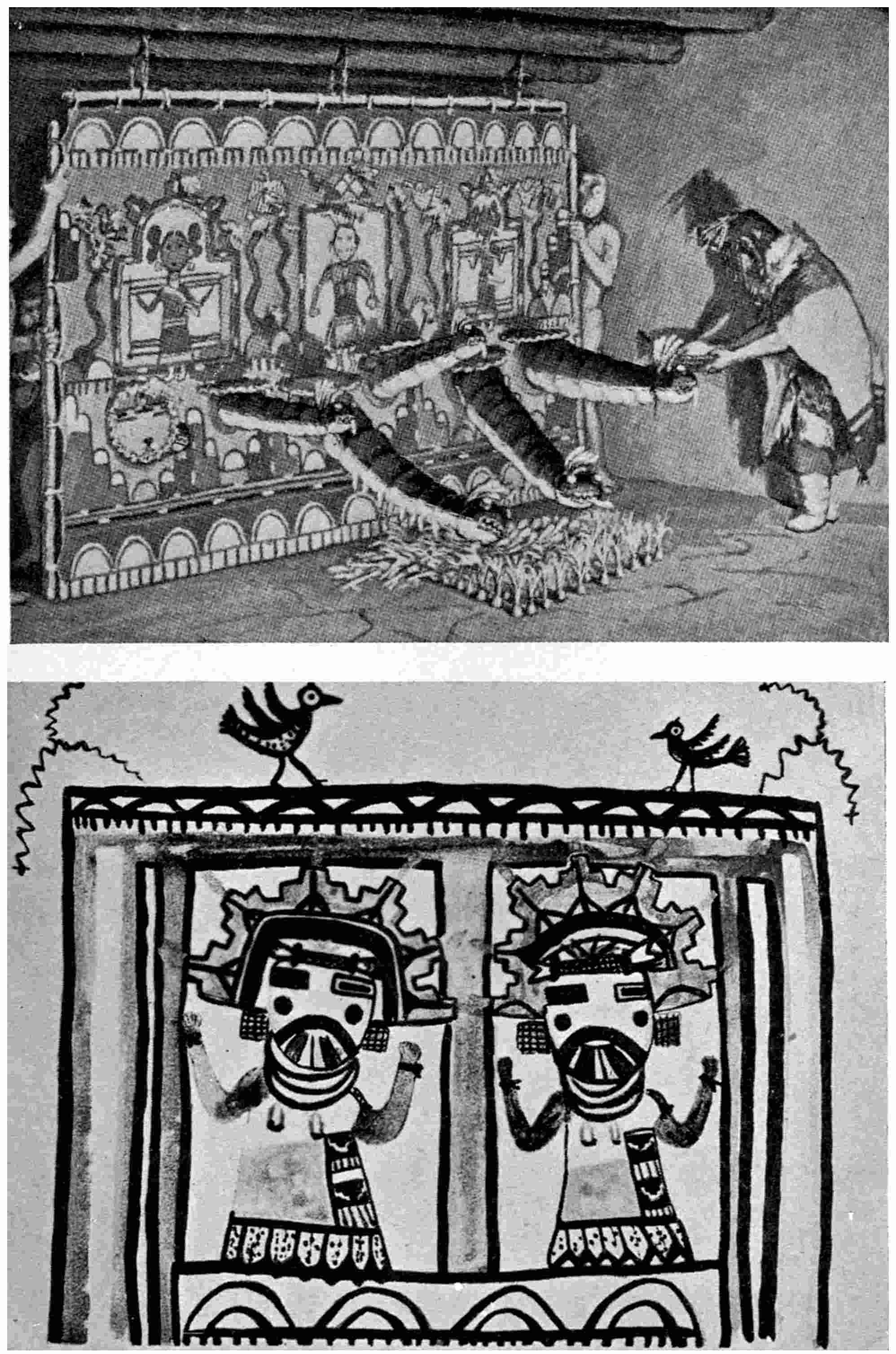

MARIONETTES EMPLOYED IN CEREMONIAL DRAMA OF THE AMERICAN INDIANS

Upper: Serpent effigies, screen and miniature corn field used in Act I of the Great Serpent Drama of the Hopi Katcinas

[From A Theatrical Performance at Walpi, by J. Walter Fewkes, in the Proceedings of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 1900, Vol. II]

Lower: Drawing by a Hopi Indian of articulated figurines of corn maidens and birds

[From Hopi Katcinas, by J. Walter Fewkes]

“The act began with a song to which the masked men, except the last mentioned, danced. A hoarse roar made by a concealed actor blowing through an empty gourd resounded from behind the screen, and immediately the circular disks swung open up-ward, and were seen to be flaps, hinged above, covering orifices through which simultaneously protruded six artificial heads of serpents, realistically painted. Each head had protuberant goggle eyes, and bore a curved horn and a fan-like crest of hawk feathers. A mouth with teeth was cut in one end, and from this orifice there hung a strip of leather, painted red, representing the tongue.

“Slowly at first, but afterwards more rapidly, these effigies were thrust farther into view, each revealing a body four or five feet long, painted, like the head, black on the back and white on the belly. When they were fully extended the song grew louder, and the effigies moved back and forth, raising and depressing their heads in time, wagging them to one side or the other in unison. They seemed to bite ferociously at each other, and viciously darted at men standing near the screen. This remarkable play continued for some time, when suddenly the heads of the serpents bent down to the floor and swept across the imitation corn field, knocking over the clay pedestals and the corn leaves which they supported. Then the effigies raised their heads and wagged them back and forth as before. It was observed that the largest effigy, or that in the middle, had several udders on each side of the belly, and that she apparently suckled the others. Meanwhile the roar emitted from behind the screen by a concealed man continued, and wild excitement seemed to prevail. Some of the spectators threw meal at the effigies, offering prayers, amid shouts from others. The masked man, representing a woman, stepped forward and presented the contents of the basket tray to the serpent effigies for food, after which he held his breasts to them as if to suckle them.

“Shortly after this the song diminished in volume, the effigies were slowly drawn back through the openings, the flaps on which the sun symbols were painted fell back in place, and after one final roar, made by the man behind the screen, the room was again silent. The overturned pedestals with their corn leaves were distributed among the spectators, and the two men by the fireplace again held up their blankets before the fire, while the screen was silently rolled up, and the actors with their paraphernalia departed.”

There are some acts in the drama into which the serpent effigies do not enter at all. In the fifth act these Great Snakes rise up out of the orifices of two vases instead of darting out from the screen. This action is produced by strings hidden in the kiva rafters, the winding of heads and struggles and gyrations of the sinuous bodies being the more realistic because in the dim light the strings were invisible.

In the fourth act two masked girls, elaborately dressed in white ceremonial blankets, usually participate. Upon their entrance they assume a kneeling posture and at a given signal proceed to grind meal upon mealing stones placed before the fire, singing, and accompanied by the clapping of hands. “In some years marionettes representing Corn Maids are substituted for the two masked girls,” Dr. Fewkes explains, “in the act of grinding corn, and these two figures are very skillfully manipulated by concealed actors. Although this representation was not introduced in 1900, it has often been described to me, and one of the Hopi men has drawn me a picture of the marionettes.”

“The figurines are brought into the darkened room wrapped in blankets, and are set up near the middle of the kiva in much the same way as the screens. The kneeling images, surrounded by a wooden framework, are manipulated by concealed men; when the song begins they are made to bend their bodies backward and forward in time, grinding the meal on miniature metates before them. The movements of girls in grinding meal are so cleverly imitated that the figurines moved by hidden strings at times raised their hands to their faces, which they rubbed with meal as the girls do when using the grinding stones in their rooms.

“As this marionette performance was occurring, two bird effigies were made to walk back and forth along the upper horizontal bar of the framework, while bird calls issued from the rear of the room.”

The symbolism of this drama is intricate and curious. The effigies representing the Great Serpent, an important supernatural personage in the legends of the Hopi Indians, are somehow associated with the Hopi version of a flood; for it was said that when the ancestors of certain clans lived far south this monster once rose through the middle of the pueblo plaza, drawing after him a great flood which submerged the land and which obliged the Hopi to migrate into his present home, farther North. The snake effigies knocking over the cornfields symbolize floods, possible winds which the Serpent brings. The figurines of the Corn Maids represent the mythical maidens whose beneficent gift of corn and other seeds, in ancient times, is a constant theme in Hopi legends.

The effigies which Dr. Fewkes saw used were not very ancient, but in olden times similar effigies existed and were kept in stone enclosures outside the pueblos. The house of the Ancient Plumed Snake of Hano is in a small cave in the side of a mesa near the ruins of Turkinobi where several broken serpent heads and effigy ribs (or wooden hoops) can now be seen, although the entrance is walled up and rarely used.

The puppet shows commonly seen to-day in the United States are of foreign extraction or at least inspired by foreign models. For many years there have been puppet-plays throughout the country. Visiting exhibitions like those of Holden’s marionettes which Professor Brander Matthews praises so glowingly are, naturally, rare. But one hears of many puppets in days past that have left their impression upon the childhood memories of our elders, travelling as far South as Savannah or wandering through the New England states. Our vaudevilles and sideshows and galleries often have exhibits of mechanical dolls, such as the amazing feats of Mantell’s Marionette Hippodrome Fairy-land Transformation which advertises “Big scenic novelty, seventeen gorgeous drop curtains, forty-five elegant talking acting figures in a comical pantomime,” or Madam Jewel’s Manikins in Keith’s Circuit, Madam Jewel being an aunt of Holden, they say, and guarding zealously with canvas screens the secret of her devices, even as Holden himself is said to have done.

Interesting, too, is the story of the retired marionettist, Harry Deaves, who writes: “I have on hand forty to fifty marionette figures, all in fine shape and dressed. I have been in the manikin business forty-five years, played all the large cities from coast to coast, over and over, always with big success; twenty-eight weeks in Chicago without a break with Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a big hit. The reason I am selling my outfit is,—I am over sixty years of age and I don’t think I will work it again.” How one wishes one might have seen that Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Chicago! In New York at present there is Remo Buffano, reviving interest in the puppets by giving performances now and then in a semi-professional way with large, simple dolls resembling somewhat the Sicilian burattini. His are plays of adventure and fairy lore.

Then, too, in most of our larger cities from time to time crude popular shows from abroad are to be found around the foreign neighborhoods. It is said that at one time in Chicago there were Turkish shadow plays in the Greek Colony; Punch and Judy make their appearance at intervals, and Italian or Sicilian showmen frequently give dramatic versions of the legends of Charlemagne.

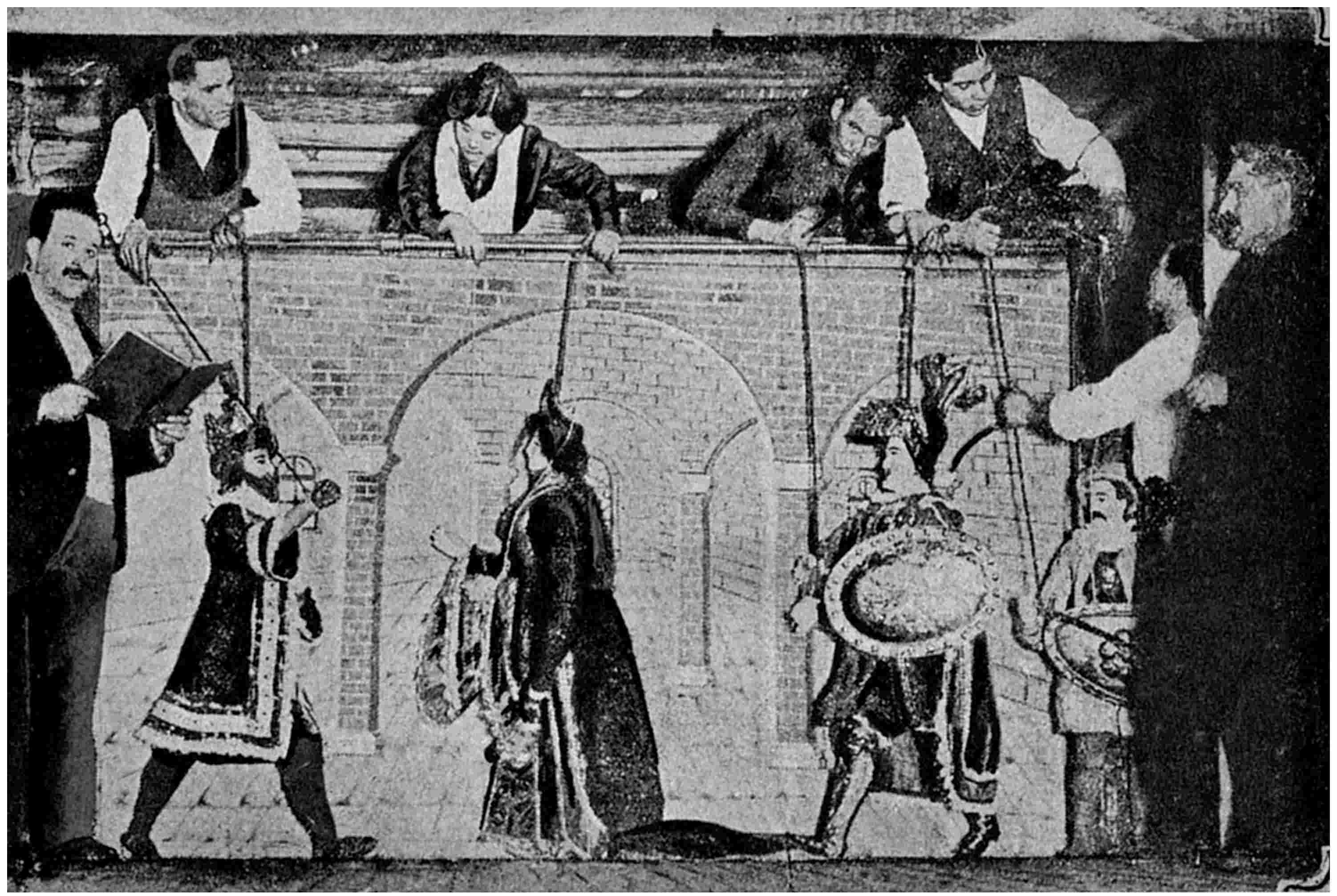

In Cleveland two years ago a party of inquisitive folk went one night to the Italian neighborhood in search of such a performance. We found and entered a dark little hall where the rows of seats were crowded closely together and packed with a spellbound audience of Italian workingmen and boys. Squeezing into our places with as little commotion as possible we settled down to succumb to the spell of the crude foreign fantoccini, large and completely armed, who were violently whacking and slashing each other before a rather tattered drop curtain. Interpreted into incorrect English by a small boy glued to my side, broken bits of the resounding tale of Orlando Furioso were hissed into my ear. But for these slangy ejaculations one might well have been in the heart of Palermo. A similar performance is described by Mr. Arthur Gleason. It was a show in New York, the master of which was Salvatore Cascio, and he was assisted by Maria Grasso, daughter of the Sicilian actor, Giovanni Grasso of Catania.

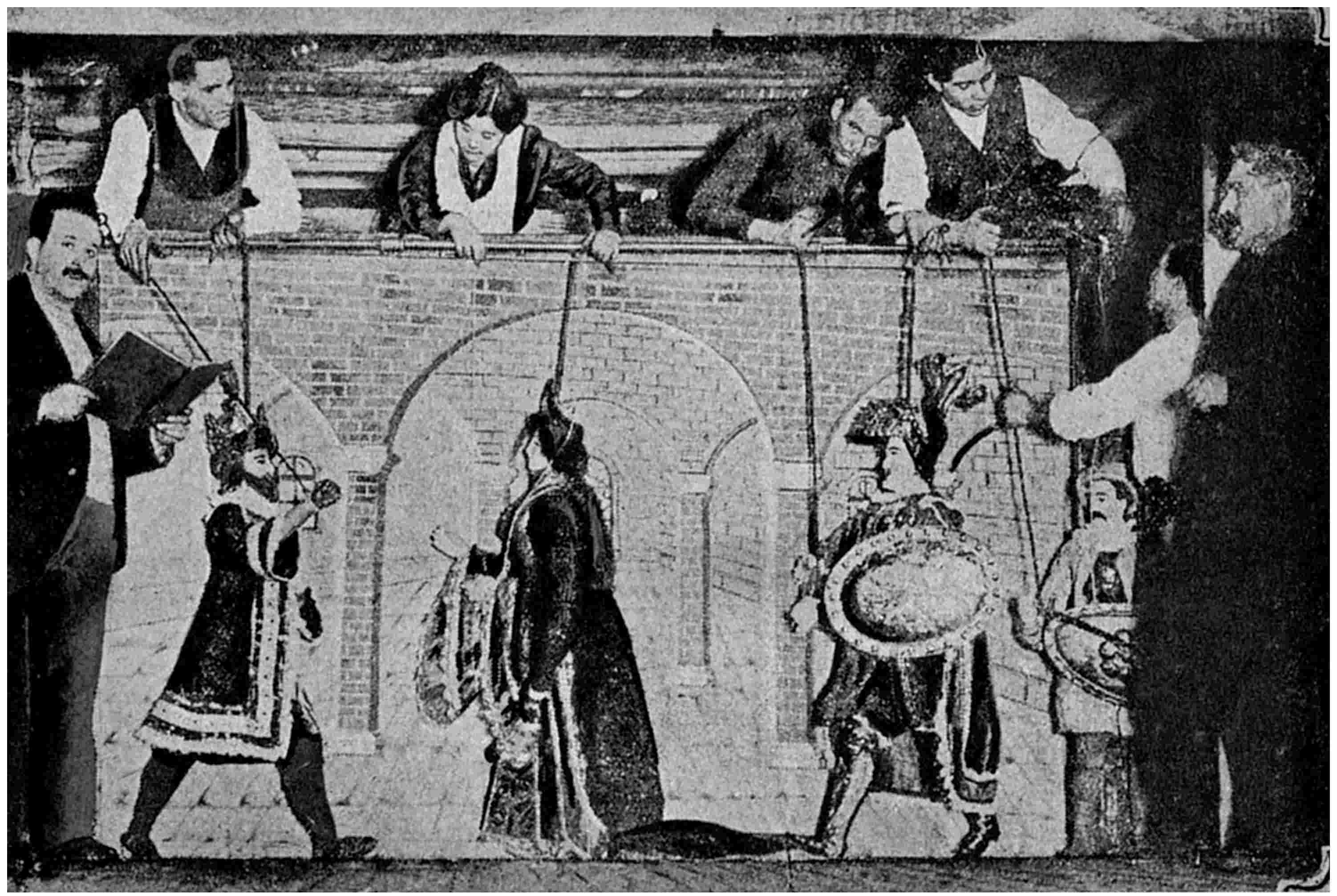

ITALIAN MARIONETTE SHOW Operated in Cleveland for a season. Proprietor, Joseph Scionte [Courtesy of Cleveland Plain Dealer]

“For two hours every evening for fifty evenings the legends unrolled themselves, princes of the blood and ugly unbelievers perpetually warring.” There was, explains Mr. Gleason, some splendid fighting. “Christians and Saracens generally proceeded to quarrel at close range with short stabbing motions at the opponent’s face and lungs. After three minutes they swing back and then clash!! sword shivers on shield!! Three times they clash horridly, three times retire to the wings, at last the Christian beats down his foe; the pianist meanwhile is playing violent ragtime during the fight, five hidden manipulators are stamping on the platform above, the cluttered dead are heaped high on the stage.” When one considers that such puppets are generally about three feet high and weigh one hundred pounds, armor and all, and are operated by one or two thick iron rods firmly attached to the head and hands, what wonder that the flooring of the stage is badly damaged by the terrific battles waged upon it and has to be renewed every two weeks!

Far removed from these unsophisticated performances, however, are the poetic puppets of the Chicago Little Theatre. I use the present tense optimistically despite the sad fact that the Little Theatre in Chicago has been closed owing to unfavorable conditions caused by the war. But although “Puck is at present cosily asleep in his box,” as Mrs. Maurice Browne has written, we all hope that the puppets so auspiciously successful for three years will resume their delightful activities, somehow or other, soon.

At first the originators of the Chicago marionettes travelled far into Italy and Germany, seeking models for their project. Finally in Solln near Munich they discovered Marie Janssen and her sister, whose delicate and fantastic puppet plays most nearly approached their own ideals. They brought back to Chicago a queer little model purchased in Munich from the man who had made Papa Schmidt’s Puppen. But, as one of the group has written, the little German puppet seemed graceless under these skies. And so, Ellen Van Volkenburg (Mrs. Maurice Browne) and Mrs. Seymour Edgerton proceeded to construct their own marionettes. Miss Katherine Wheeler, a young English sculptor, modelled the faces, each a clear-cut mask to fit the character, but left purposely rough in finish. Miss Wheeler felt that the broken surfaces carried the facial expression farther. The puppets were fourteen inches high, carved in wood. The intricate mechanism devised by Harriet Edgerton rendered the figures extremely pliable. Her mermaids, with their serpentine jointing, displayed an uncanny sinuousness. Miss Lillian Owen was Mistress of the Needle, devising the filmy costumes, and Mrs. Browne with fine technique and keen dramatic sense took upon herself the task of training and inspiring the puppeteers as well as creating the poetic ensemble.

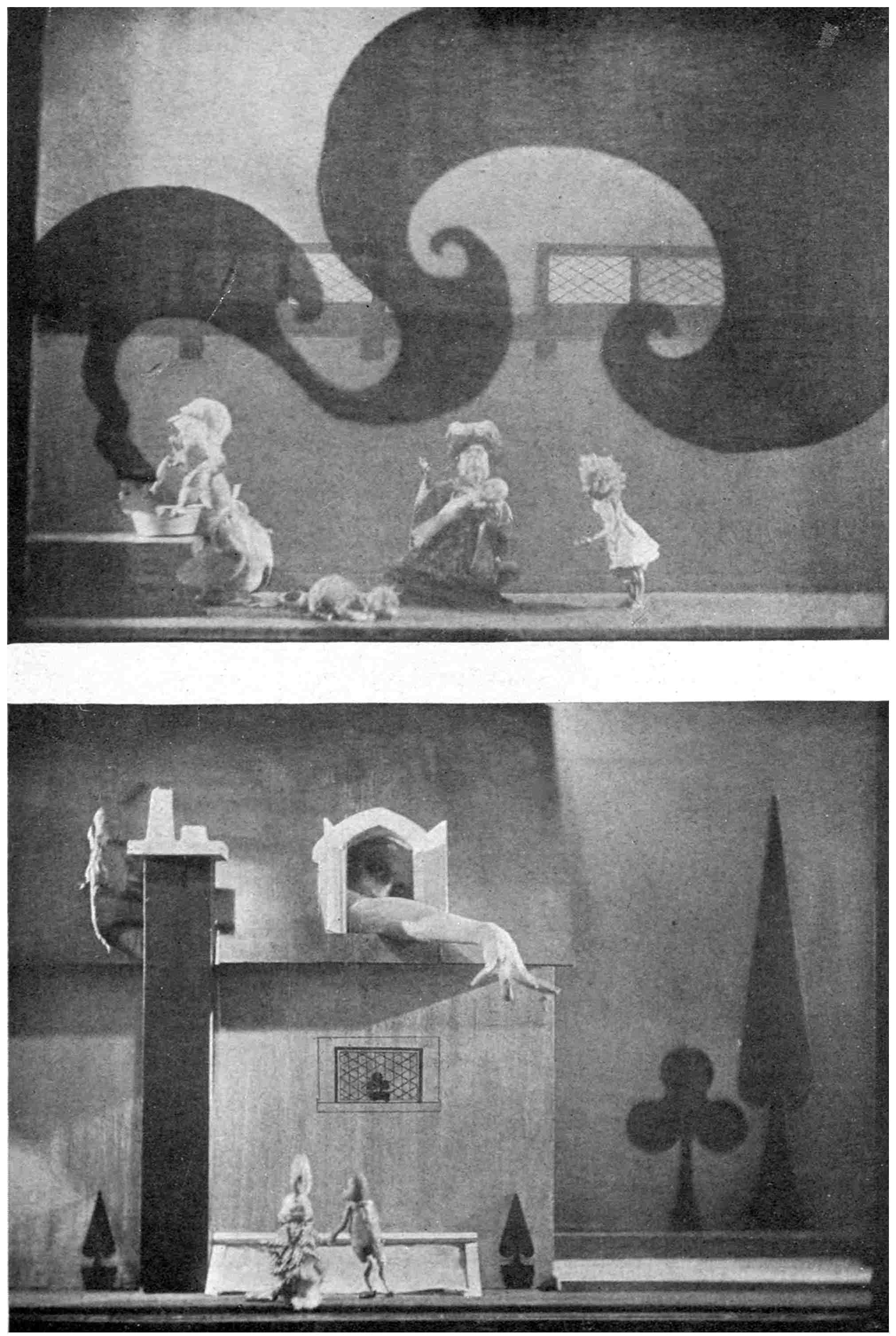

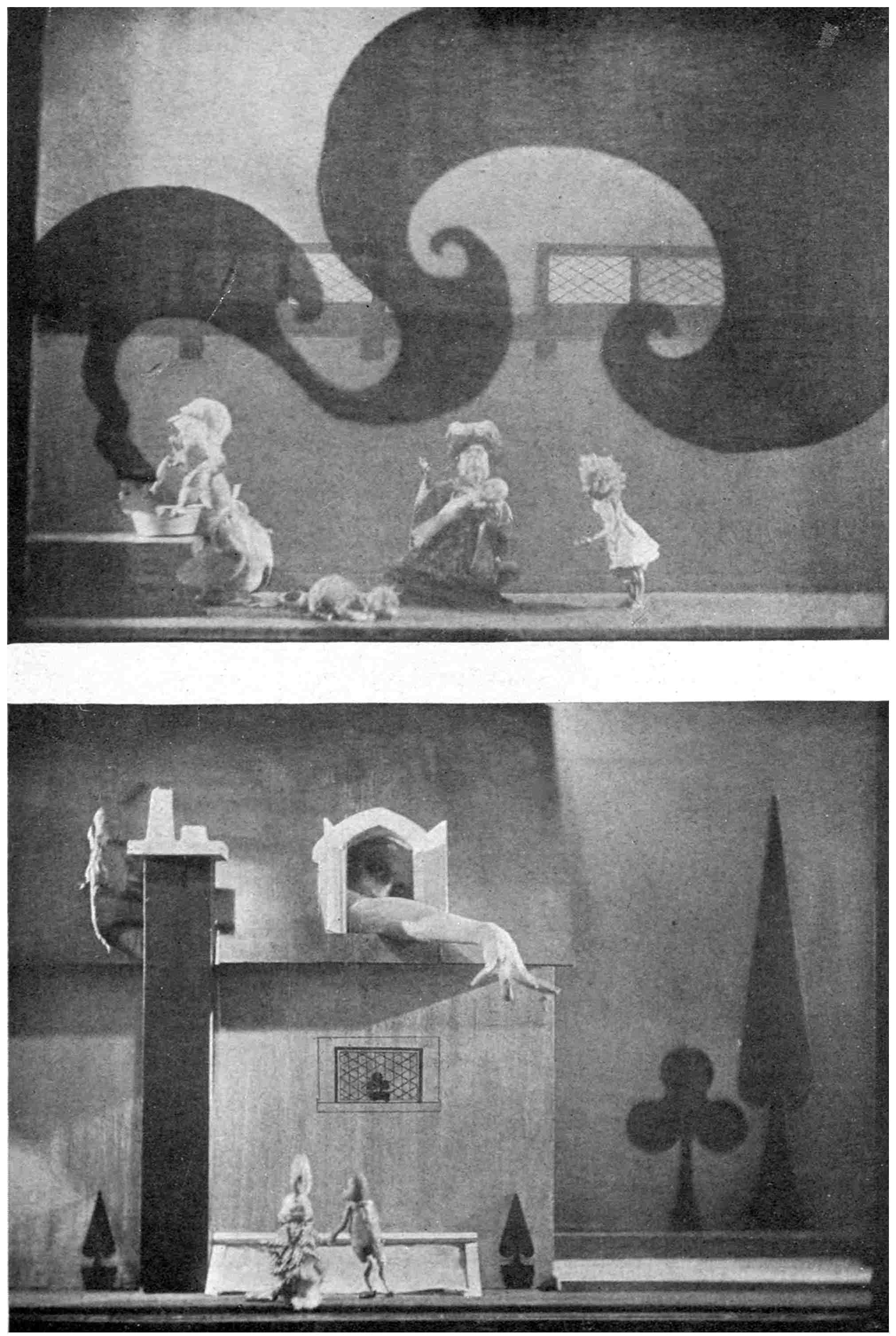

MARIONETTES AT THE CHICAGO LITTLE THEATRE

Production of Alice in Wonderland under Mrs. Maurice Browne’s direction

Upper: The Duchess’s Kitchen

Lower: The White Rabbit’s House

The Chicago puppets are neither grotesque nor humorous and they have little in common with the puppet of tradition. Theirs is an element of exquisite magical fairy-land, with dainty beings moving about in it, who can express beauty, tragedy and tenderness. Their repertoire consists for the most part of fantasies written or adapted by members of the group. The first was a delicious fairy adventure, a play for children, The Deluded Dragon, founded upon an old Chinese legend, wherein a lovely Prince seems to follow a Wooden Spoon down the River certain that he will chance upon Adventure, which he does. The play was decidedly successful, despite a most unfortunate accident at the first performance caused by the impetuosity of the somewhat hurried puppeteers. To be more explicit, “the fierce but fragile dragon parted in the middle, his five heads swinging free of his timorously lashing tail.” “The same year,” continues Miss Hettie Louise Mick, herself puppeteer and composer of marionette plays, “Reginald Arkell’s charming fantasy, Columbine, was produced with more patience and proved a wholly delightful and almost finished thing.”

The next year two fairy tales were presented, Jack and the Beanstalk and The Little Mermaid, both dramatized by the puppeteers. Great technical advances had been made in the latter play and a delicate, fantastic effect attained, approaching the ideals of the founders. The last and most ambitious performance of this season was Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, given not only for children but openly for the grown-ups. Of this production Miss Mick has written: “Puck, who had been known formerly as the rather stiff little fairy who introduced and closed each play in rhyme, now became his romping, pliant self, tumbling through the air, doubling up in chortling glee upon his toadstool and pushing his annoying little person into every disconcerted mortal’s way. Titania emerged, a glowing queen of filmy draperies, attended by flitting elves, and Oberon resumed his crafty, flashing earth-character, his attendants being two inflated and wholly impudent bugs. The Mechanicals, while clumsy, fulfilled their parts well and brought the outworn humor of Shakespeare into hilarious reality, the scene between Pyramus and Thisbe never failing to bring roars of appreciation from the audience. Only the Greeks were a dank and dismal failure. Hurriedly constructed to meet the rapidly approaching production date, they were awkward, long-headed, stiff-jointed creatures highly unlike their graceful originals. But the lighting and settings, and the prevailing atmosphere of exquisite unreality were such that the audience came night after night for five weeks, and at the end of that time, when the theatre closed for the season, demanded more.”

Mrs. Browne, in an informal letter about her puppets, has written concerning this performance: “I don’t think I ever have seen such delicate beauty as was achieved at the end of the Midsummer: I say it in all simplicity because I have a curious, Irish feeling that the little dolls took matters into their own hands and for once allowed us a glimpse into their own secret world. The audience, whether of adults or of children, never failed to respond with a sudden hush and the poor, tired girls who had been working in great heat over the colored lights for two hours never failed to get their reward.” Mrs. Browne then proceeded to give an idea of the patient toil behind the scenes. “We rehearsed six hours a day for about seven weeks to prepare the play. Six girls worked the puppets; there were about thirty of them, so you can see how many characters each girl had to create and how many dolls she had to work (my puppeteers spoke for each puppet they handled). Besides the actual workers, I had an understudy whose duty it was to stand on the platform back of the girls to take their puppets from them when the scenes were moving quickly and many characters were leaving the stage at once; she then hung the puppets where they could be easily reached for their next entrance. Hers was, of course, the most thankless task of all because she had none of the pleasure, and the accuracy of the performance depended upon her efficiency. None who have not worked with puppets can understand the nervous strain of these performances.”

The third year of the Chicago puppets saw progress in many directions. The enthusiasm of the puppeteers had finally been aroused to the point where each contributed suggestions in the line of mechanical construction or the adapting of plays. Mr. H. Carrol French of the South Bend Little Theatre came to be puppet manager and added many improvements to the mechanism of the dolls, constructing the bodies of wire instead of wood (some suggestions for which he received through the courtesy of Mr. Tony Sarg). The new dolls were more sensitive to manipulation than the old, and more individual in their gestures. The repertoire for this season consisted of two little fairy plays, The Frog Prince and Little Red Riding Hood, adaptations of Miss Mick, and then Alice in Wonderland, made into a play by Mrs. Browne. While this play never wove so strong a poetic spell as A Midsummer Night’s Dream, it marked great strides in skill on the part of the manipulators. This same year the little puppets went on a tour, not only into the suburbs of Chicago but, under the auspices of the Drama League, as far as St. Louis. Let us hope that at some not too distant date Puck, moving sprite among this brave and poetic band of marionettes, will gaily revive and travel farther with his troupe so that we all may witness and enjoy his fairy charms.5

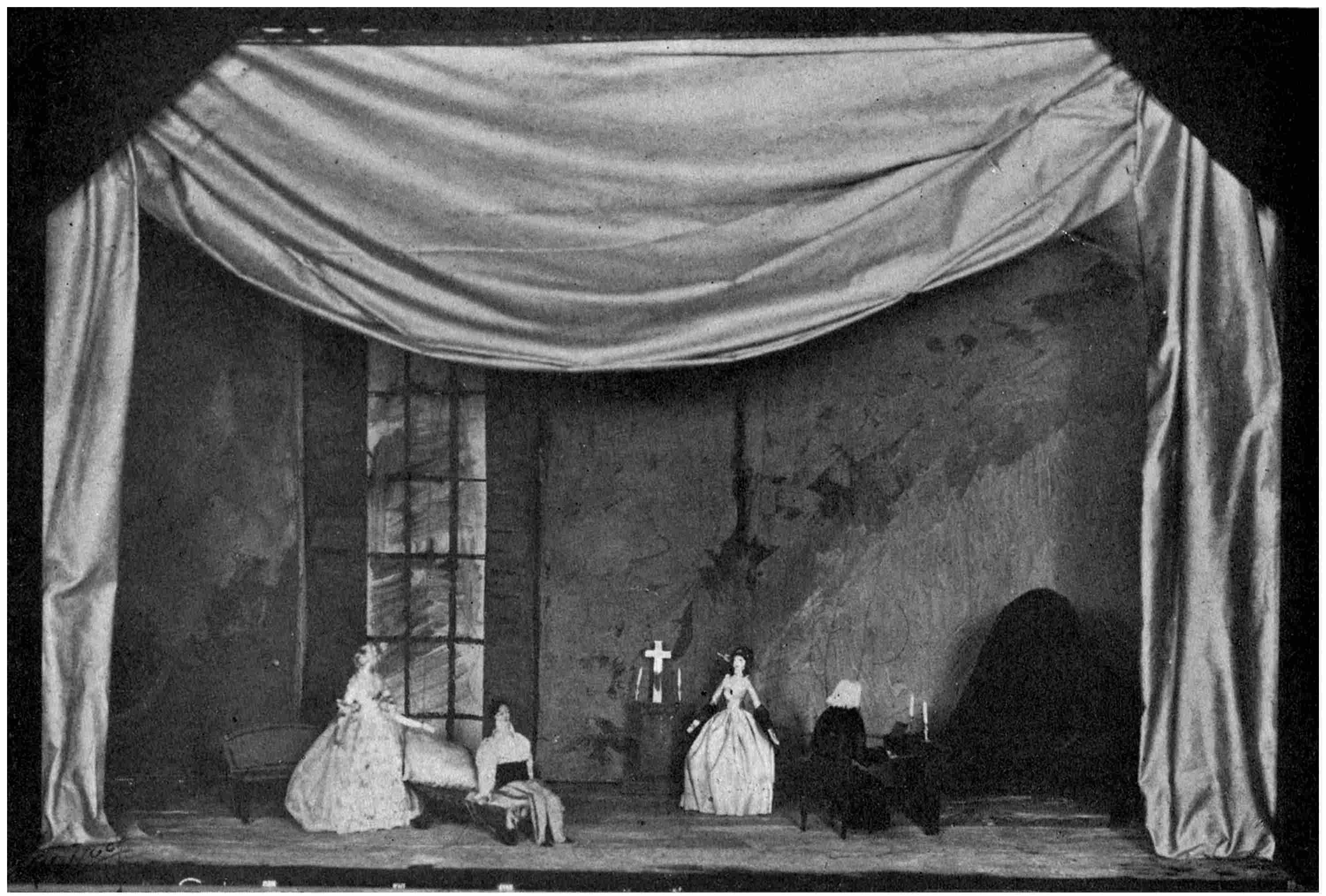

MARIONETTES AT THE CLEVELAND PLAY HOUSE

Presenting The Life of Chopin

Puppets and scenery designed by Carl Broemel

The Cleveland Playhouse has had its puppet stage from the very beginning of the organization. Mr. Raymond O’Neil, the director, has always taken a great interest in the puppets. He believes, with Mr. Gordon Craig, that they might well serve as models in style, simplicity and impersonality for living actors, but he also avers that they are capable of presenting certain types of drama as effectively if not more satisfactorily than the best of actors, and certainly better than any second-rate performers. When the Cleveland Playhouse was still a very small, informal group it was decided to produce a serious marionette play. The director selected for this purpose The Death of Tintagiles, written by Maeterlinck expressly for puppets. A Cleveland artist, Mr. George Clisby, worked out the proper proportions for the marionettes and the stage and their relation to each other. It is recognized by all who witness them that the effectiveness and success of the Cleveland productions are due in great part to the happy proportions prevailing in the marionette scenes and the sense of a complete, harmonious whole which they create.

Mr. Clisby also designed the costumes for the first dolls, and the scenery. Only the significant and essential was allowed upon his little stage, strong, simple lines and colors, a few poplar trees upon a hilltop in the blue dusk of the evening, or plain, gloomy chambers with high arches leading away into mysterious passages, or at the very last, merely a door, a massive, closed iron door set in bare walls. The figures were planned in the same spirit. Being very small they were given practically no features, a scowling eyebrow, a dignified beard, long hair or short, stiff or flowing, being sufficient indication of the type represented.

Miss Grace Treat, who made and dressed most of the marionettes, caught and embodied the artist’s ideal in strange, tall puppets, naïve but marvelously impressive. The construction of these puppets, although extremely simple, had to be planned and executed patiently. Often a marionette was taken apart and made over again until the right effect, or the proper gesture, was obtained. The puppets are somewhat like rag dolls, of a soft material, stuffed with cotton or scraps, weighted and carefully balanced with lead. Five and at most seven strings are used and the control is very primitive. This studied simplicity in structure and in costume has given the Cleveland puppets a naïve style,—their limitations both defining and emphasizing the significance of each little figure. Miss Treat was also the master-manipulator of the puppets and in her hands the stiff little Ygraine took on heroic and tragic proportions.

For many months a small group of faithful enthusiasts struggled to attain the standard set for them by director and artist. The play was finally given before an audience of Playhouse members. Mr. O’Neil produced the strangely beautiful lighting with the crudest facilities imaginable. The parts were read by members of the group who had been working along patiently with the manipulators until words, settings and action had grown perfectly harmonious. Those who were privileged to witness this first production were deeply thrilled by the poetic beauty of it, and still mention it as an unusual experience.

Encouraged by this initial success, the group determined to continue with marionettes. But the Playhouse itself was going through a winter of vicissitudes and the puppeteers were compelled to endure and suffer many delays and disappointments. Rehearsing in a rear room of an empty house loaned for the season (and often fabulously cold!) with readers and operators dropping out one by one from sheer discouragement or because of war work, trying out several plays which for one reason or another proved impossible, still a nucleus of the old group, with the addition of a few new workers, held on, held out through this second season under the ever optimistic leadership of Grace Treat. After moving into other temporary quarters, to be exact, into the high and dingy little ball-room of an old residence turned boarding-house, the group produced a very successful repetition of Tintagiles.6

Meanwhile the Playhouse had purchased a little church which it remodeled, decorated and equipped as a permanent theatre. During this time, and under most trying circumstances brought about by the war, the director contrived to present several productions for the first Winter in the new playhouse, among them two marionette performances. Most of the puppeteers and readers for both of these plays were new at the work and had to be trained from the very beginning. The stage, too, had been altered to admit of a cyclorama, improved lighting arrangements and, quite incidentally, a stronger and safer bridge. Nevertheless certain methods and principles of manipulating were evolved which somewhat raised the dexterity of the group as a whole.

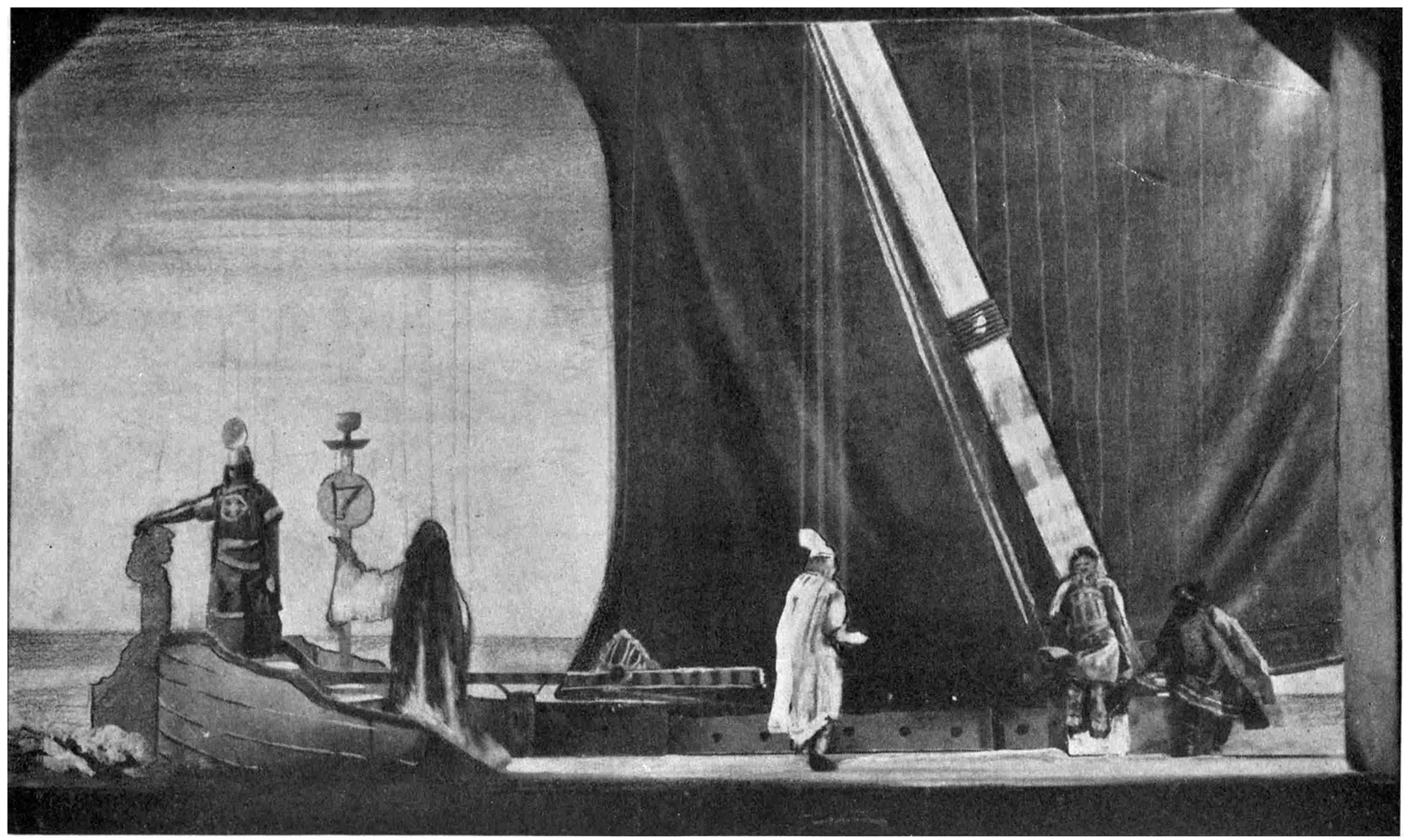

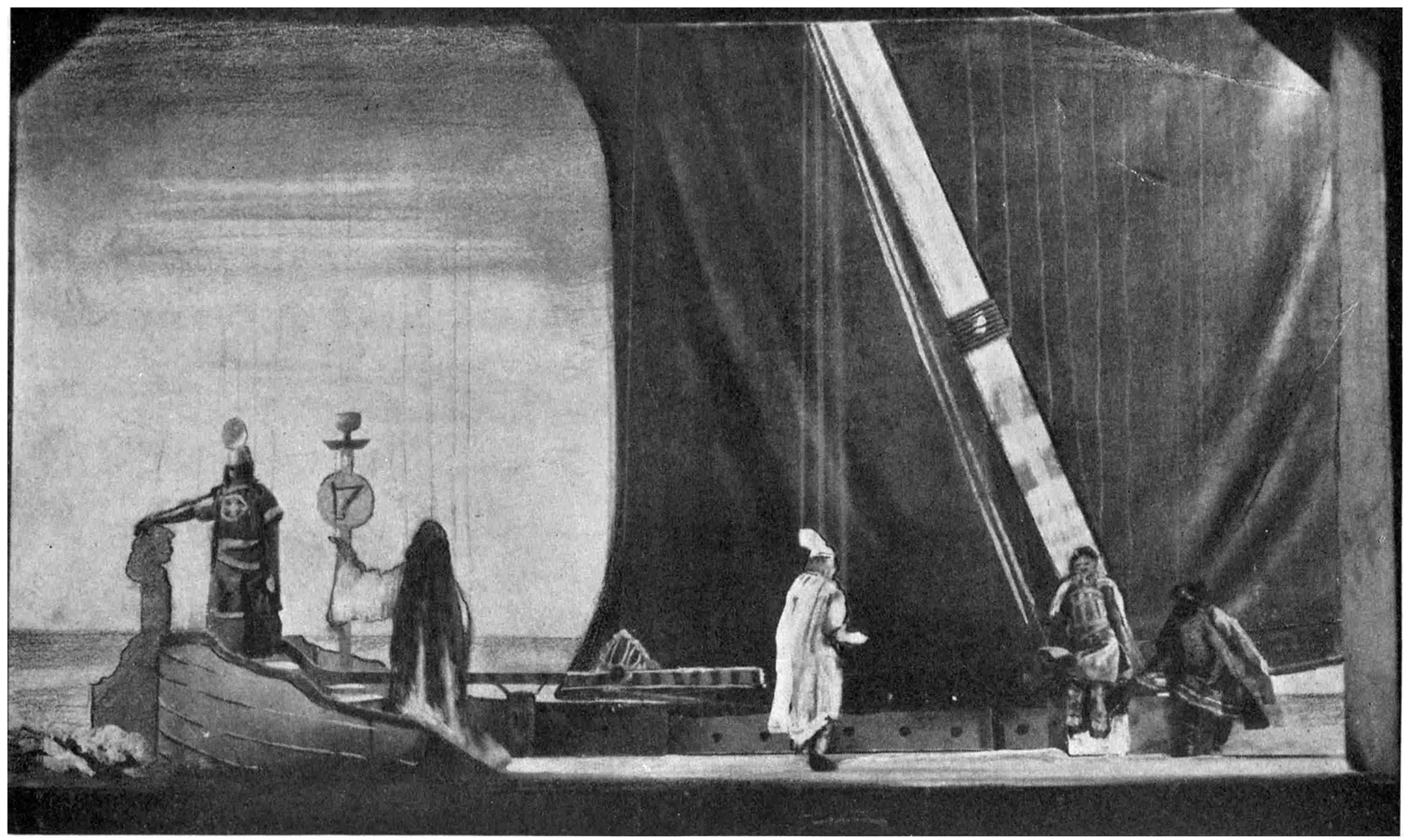

One of the plays we produced was Shadowy Waters by Yeats, a dreamy, far-away, old Irish drama which lent itself beautifully to our type of poetic puppets. Mr. John Black designed the colorful costumes and the scene upon the deck of a vessel. The pleasure of making and dressing the impressionistic dolls was delegated to me, but all willing members of the group were allowed to share in this privilege. There were five long-suffering readers and four patient operators, besides the director of the group, who also manipulated, with extra assistance, at the very end, to carry the marionettes back and forth behind the scene. Mr. O’Neil also generously helped in staging the production. Many and varied were the rehearsal evenings we spent together. But, when at last the curtain slowly fell upon the Queen in her turquoise gown with “hair the color of burning” and her dark, melancholy lover beside her, deserted by the sailors and drifting away over shadowy blue waters to the strains of the magic harp, we all felt that we had created something of beauty, despite our inexperience and obvious shortcomings.

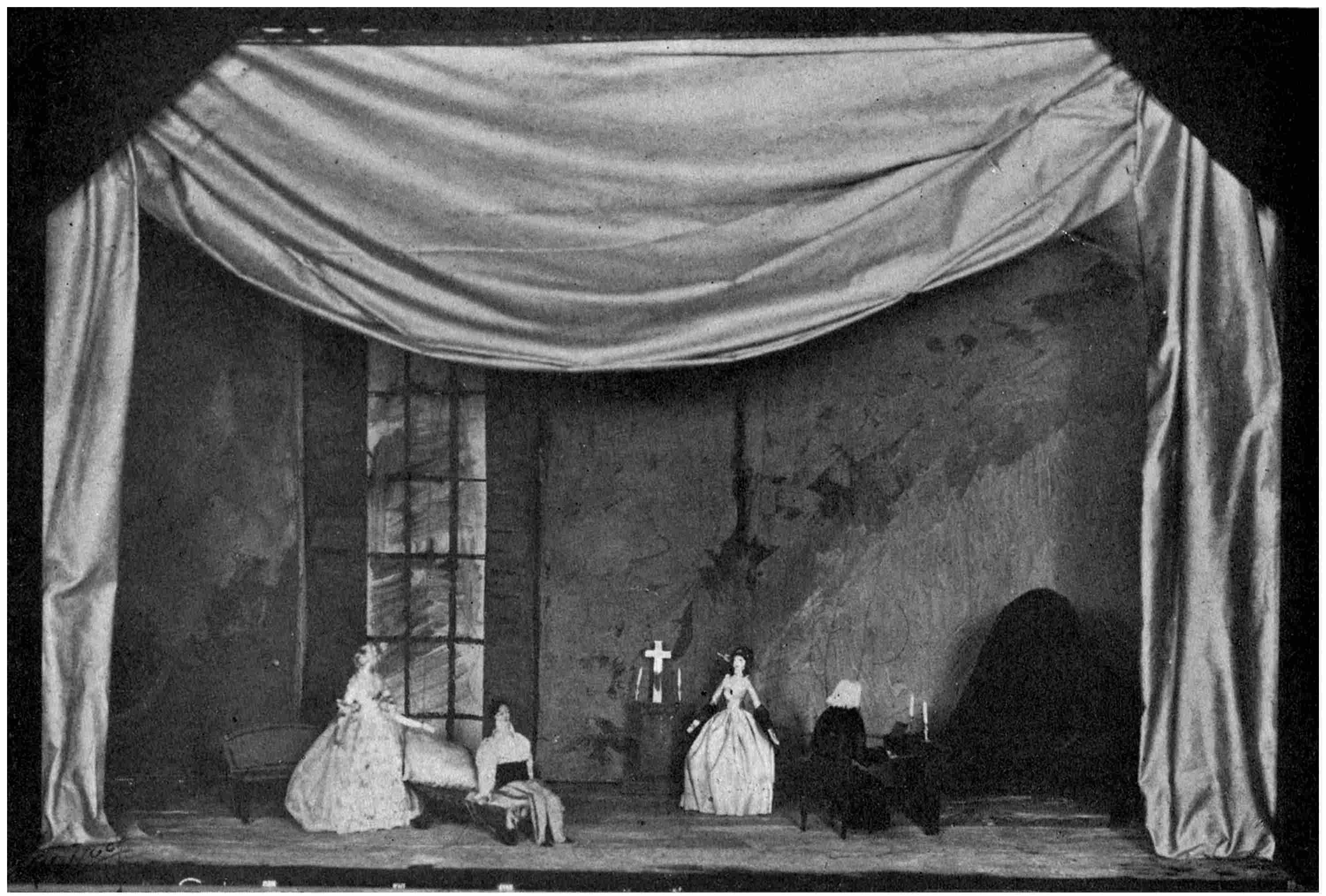

MARIONETTES AT THE CLEVELAND PLAY HOUSE

Production of Shadowy Waters by W. B. Yeats

Puppets and scenery designed by John Black

The other puppet play was somewhat in the nature of a departure at the Playhouse. A little narrative of the life of Chopin, written by Mr. Albert Gehring, was read to the accompaniment of piano selections from Chopin’s music while dainty little figures of the period, gently moving, enacted the scenes in the story as it proceeded. This method has had many and ancient precedents in the ambulent puppet shows of the Middle Ages. The success of the experiment has suggested to some puppeteers in the group the idea of further attempts in this manner. Mr. Carl Broemel was the artist who designed the elegantly clad and exquisite little dolls, as well as the setting for the play. The latter was a remarkable example of a miniature interior which, despite its diminutive furnishings, had nothing petty about it but gave one the unified, powerful effect of a dignified painting, poetically and simply conceived.

Thus the Cleveland puppets have struggled along through hard days of war