Puppets of Antiquity

“I wish to discant on the marionette.

One needs a keen taste for it and also a little veneration.

The marionette is august; it issues from a sanctuary....”

ANATOLE FRANCE

PERHAPS the most impressive approach to the marionettes is through the trodden avenue of history. If we travel from distant antiquity where the first articulated idols were manipulated by ingenious, hidden devices in the vast temples of India and Egypt, if we follow the footprints of the puppets through classic centuries of Greece and Rome and trace them even in the dark ages of early Christianity whence they emerged to wander all over mediaeval Europe, in the cathedrals, along the highways, in the market places and at the courts of kings, we may have more understanding and respect for the quaint little creatures we find exhibited crudely in the old, popular manner on the street corner or presented, consciously naïve and precious, upon the art stage of an enthusiastic younger generation. For the marionette has a history. No human race can boast a longer or more varied, replete with such high dignities and shocking indignities, romantic adventure and humble routine, triumphs, decadences, revivals. No human race has explored so many curious corners of the earth, adapted itself to the characteristic tastes of such diverse peoples and, nevertheless, retained its essential, individual traits through ages of changing environment and ideals.

The origin of the puppet is still somewhat of a mystery, dating back, as it undoubtedly does, to the earliest stages of the very oldest civilizations. Scholars differ as to the birthplace and ancestry. Professor Richard Pischel, who has made an exhaustive study of this phase of the subject, believes that the puppet came into being along with fairy tales on the banks of the Ganges, “in the old wonderland of India.” The antiquity of the Indian marionette, indeed, is attested by the very legends of the national deities. It was the god Siva who fell in love with the beautiful puppet of his wife Parvati. The most ancient marionettes were made of wool, wood, buffalo horn and ivory; they seem to have been popular with adults as well as with children. In an old, old collection of Indian tales, there is an account of a basketful of marvellous wooden dolls presented by the daughter of a celebrated mechanician to a princess. One of these could be made to fly through the air by pressing a wooden peg, another to dance, another to talk! Large talking puppets were even introduced upon the stage with living actors. An old Sanskrit drama has been found in which they took part. But in India real puppet shows, themselves, seem to have antedated the regular drama, or so we may infer from the names given to the director of the actors, which is Sutradhara (Holder of the Strings) and to the stage manager, who is called Sthapaka (Setter up). The implication naturally is that these two important functionaries of the oldest Indian drama took their titles from the even more ancient and previously established puppet plays.

There are authorities, however, who consider Egypt the original birthplace of the marionette, among these Yorick (P. Ferrigni), whose vivid history of puppets is accessible in various issues of The Mask. Yorick claims that the marionette originated somehow with the aborigines of the Nile and that before the days of Manete who founded Memphis, before the Pharaohs, great idols moved their hands and opened their mouths, inspiring worshipful terror in the hearts of the beholders. Dr. Berthold Laufer corroborates this opinion. He maintains that marionettes first appeared in Egypt and Greece, and spread from there to all countries of Asia. The tombs of ancient Thebes and Memphis have yielded up many small painted puppets of ivory and wood, whose limbs can be moved by pulling a string. These are figures of beasts as well as of men and they may have been toys. Indeed, it is often claimed that puppets are descended, not from images of the gods, but from “the first doll that was ever put into the hands of a child.”

The Boston Transcript, in 1904, published a report of an article by A. Gayet in La Revue which gives a minute description of a marionette theatre excavated at Antinoë. There, in the tomb of Khelmis, singer of Osiris, archaeologists have unearthed a little Nile galley or barge of wood with a cabin in the centre and two ivory doors that open to reveal a stage. A rod across the front of this stage is supported by two uprights and from this rod light wires were found still hanging. Other indications leave little doubt that this miniature theatre was used in a religious rite, possibly on the anniversary of the death of the god Osiris, whose father was Ra, the sun, as a sort of passion play performed by puppets before an audience of the initiated. Mortuary paintings show us the ritual and tell us the story. As everything excavated at this site is reported to be of the Roman or Coptic period this is probably the oldest marionette theatre ever discovered!

The Chinese puppets and still older shadows of the land as well as of other Oriental countries are all of considerable antiquity. In truth, it matters little whence came the first of the puppets, from India, Egypt or from China, nor how descended, from the idols of priests or the playthings of children. It is enough to know of their indisputably ancient lineage and the honorable position granted them in the legends of gods and heroes. Whatever remains uncertain or fantastic in the theories of their origin can only add to the aura of romance surrounding this imperishable race of fragile beings.

* * * * *

In the mythology of the Greeks one may find mention of the august ancestors of the marionettes. Passages in the Iliad describe the marvellous golden tripods fashioned by Vulcan which moved of themselves. A host of great articulated idols were to be found in the temples all over Greece. These were moved, Charles Magnin avers, by various devices such as quicksilver, leadstone, springs, etc. There was Jupiter Ammon, borne upon the shoulders of the priests, who indicated with his head the direction he wished to travel. There were the Apollo of Heliopolis, the Theban Venus, the statues created by Daedalus and many others, all manipulated by priests from within the hollow bodies.

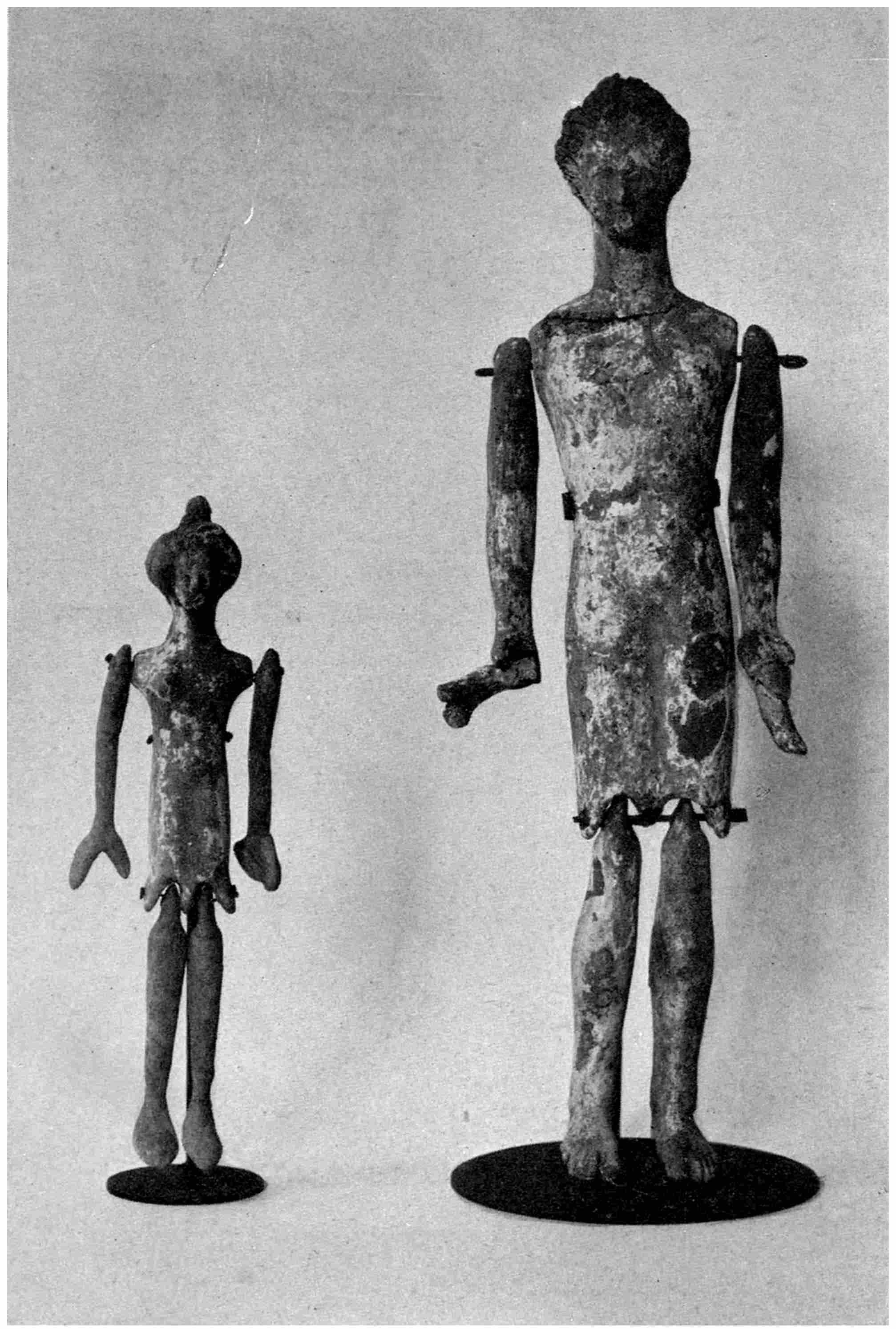

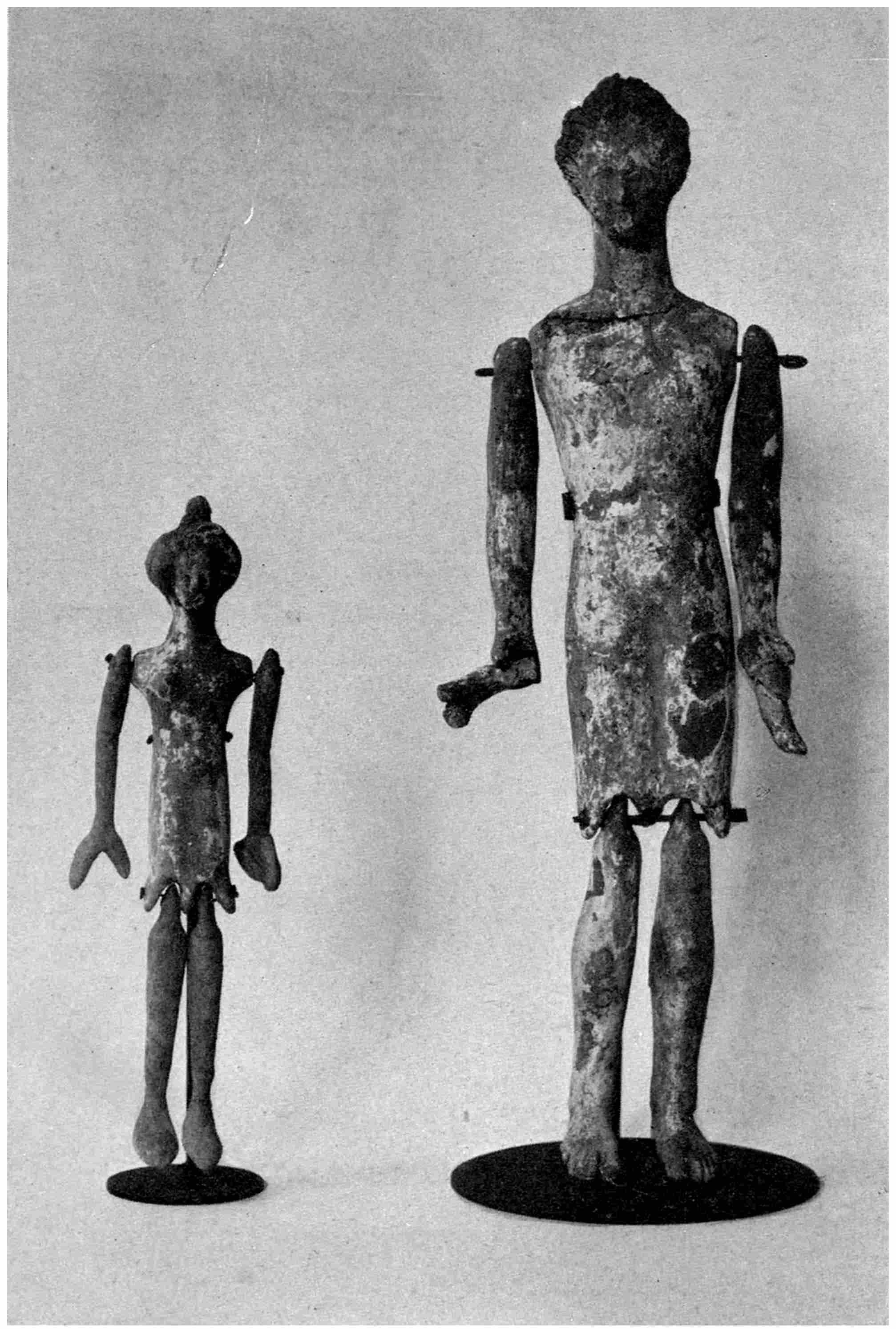

JOINTED DOLLS OR PUPPETS

Terra-cotta, probably Attic

[Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston]

But aside from these inspiring deities, in fact right along with them, Greek puppetry grew up and flourished. Yorick writes, “Greece from remotest times of which any accounts have come down to us had marionette theatres in the public places of all the most populated cities. She had famous showmen whose names, recorded on the pages of the most illustrious writers, have triumphed over death and oblivion. She had her ‘balletti’ and pantomimes exclusively conceived and preordained for the play of ‘pupazzi,’ etc.” Eminent mathematicians interested themselves in perfecting the mechanism of the dolls until, as Apuleius wrote, “Those who direct the movement of the little wooden figures have nothing else to do but to pull the string of the member they wish to set in motion and immediately the head bends, the eyes turn, the hands lend themselves to any action and the elegant little person moves and acts as though it were alive.” A pleasant hyperbole of Apuleius perhaps, but some of us credulously prefer to have faith in it.

In the writings of the celebrated Heron of Alexandria, living two centuries before Christ, one can find a very minute description of a puppet show for which he planned the ingenious mechanism. He explains that there were two kinds of automata, first those acting on a movable stage which itself advanced and retreated at the end of the acts and second, those performing on a stationary stage divided into acts by a change of scene. The Apotheosis of Bacchus was of the first type, the action presented within a miniature temple wherein stood the statue of the god with dancing bacchantes circling around, fountains jetting forth milk, garlands of flowers, sounding cymbals, all accomplished by a mechanism of weights and cords. It was an extremely elaborate affair. Of the second type of puppet show Heron cites as example The Tragedy of Nauplius, the mechanism for which was invented by a contemporary engineer, Philo of Byzantium. There were five scenes disclosed, one after the other, by doors which opened and closed: first, the seashore, with workmen constructing the ships, hammering, sawing, etc.; second, the coast with the Greeks dragging their ships to the water; third, sky and sea, with the ships sailing over the waters which begin to grow rough and stormy; fourth, the coast of Euboë, Nauplius brandishing a torch on the rocks and shoals whither the Greek vessels steer and are shattered (Athene stands behind Nauplius, who is the instrument of her vengeance); fifth, the wreck of the ships, Ajax struggling and drowning in the waves, Athene appearing in a thunder clap! This play was probably taken from episodes of the Homeric legend and, although Heron does not so state, the action of the puppets was most likely accompanied by a recital of the poem upon which the drama was founded.

Xenophon describes still another type of show, a banquet at which the host brought in a Syracusan juggler to amuse the guests with his dancing marionettes. The best showmen in Greece seem to have been Sicilians. These peripatetic showmen went from town to town with their figures in a box. The plays they presented were generally keen, strong satires on the foibles of human nature, the vices of the times, the prominent or pompous persons of the day, parodies on popular dramas or schools of philosophy. They were a favorite diversion of the masses and of cultured people as well. Even Socrates is reported to have bandied words with a Sicilian showman, asking him how he made a living in his profession. To which the showman made reply: “The folly of men is an inexhaustible fund of riches and I am always sure of filling my purse by moving a few pieces of wood.” Eventually the puppets usurped a place upon the classic stage itself, and it is reported that a puppet player, Potheinus, had a small stage specially erected for his marionettes on the thymele of the great theatre of Dionysius at Athens where Euripedes’ plays had been presented.

* * * * *

The Romans borrowed marionette traditions from the Greeks as they did many other art forms. There were large articulated statues of the gods and emperors in Rome. At Praeneste the celebrated group of the infants of Jupiter and Juno seated upon the knees of Fortune appears to have been of this sort; the nurse seems to have been movable. Livy describes a banquet celebration and the terror of the people and of the Senate upon hearing that the gods averted their heads from the dishes presented them. Ovid, also, gives an account of the startling effect produced upon the beholders when the statue of Servus Tullius moved. As in Greece, there were special puppet performances given in private homes as well as the wandering shows along the highways. The latter were popular with common people, with poets, philosophers and emperors. Marcus Aurelius wrote about them, Horace and Persius mentioned them.

The personages of the Roman puppet stage generally represented obvious and amusing types of humanity; their repertoire consisted chiefly of bold satire and parodies on popular dramas. The conventionalized characters of Roman marionette theatres were not at all dissimilar from the later heroes of the Italian fantoccini. A bronze portrait of Maccus, the Roman buffoon, which was unearthed in 1727, might serve almost as a statue of Pulcinella, hooked nose, nut-cracker chin, hunchback and all. In fact it is thought that these Roman mimes or sanni have lived on in the Italian burattini, and in the characters of the Commedia dell’ Arte. This theory has been criticized by some who feel that the personaggi such as Arlecchino and Pulcinella grew out of the mannerisms and characteristics of the Italians, just as the puppet buffoons of Rome were true offspring of the Roman people, and that any resemblances between them may be laid at the door of common frailties existing in humanity of all ages and ever fit subject for the satirical play of puppets. Nevertheless it is not impossible to believe that through the curiously confused period in Italy when Pagan culture was giving way to Christianity, when heathen ideals were half perishing, half persisting, something of the old was embodied in, assimilated with the new. And so it may have happened with the marionettes, Maccus emerging with much of Pulcinella, Citeria appearing as Columbine. We have Pappus Bruccus and Casnar, the parasite, the glutton, the fool, passed on somehow.

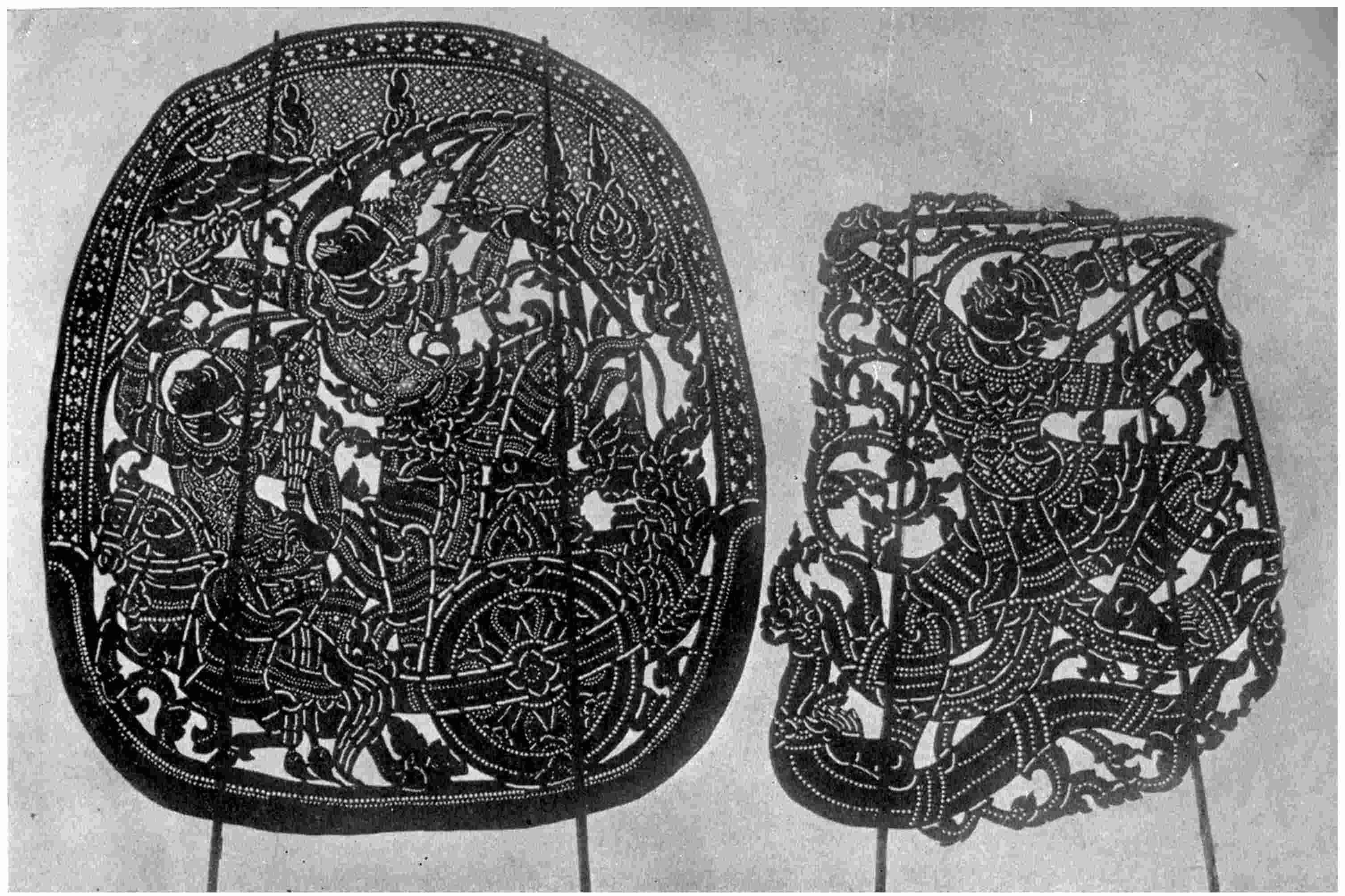

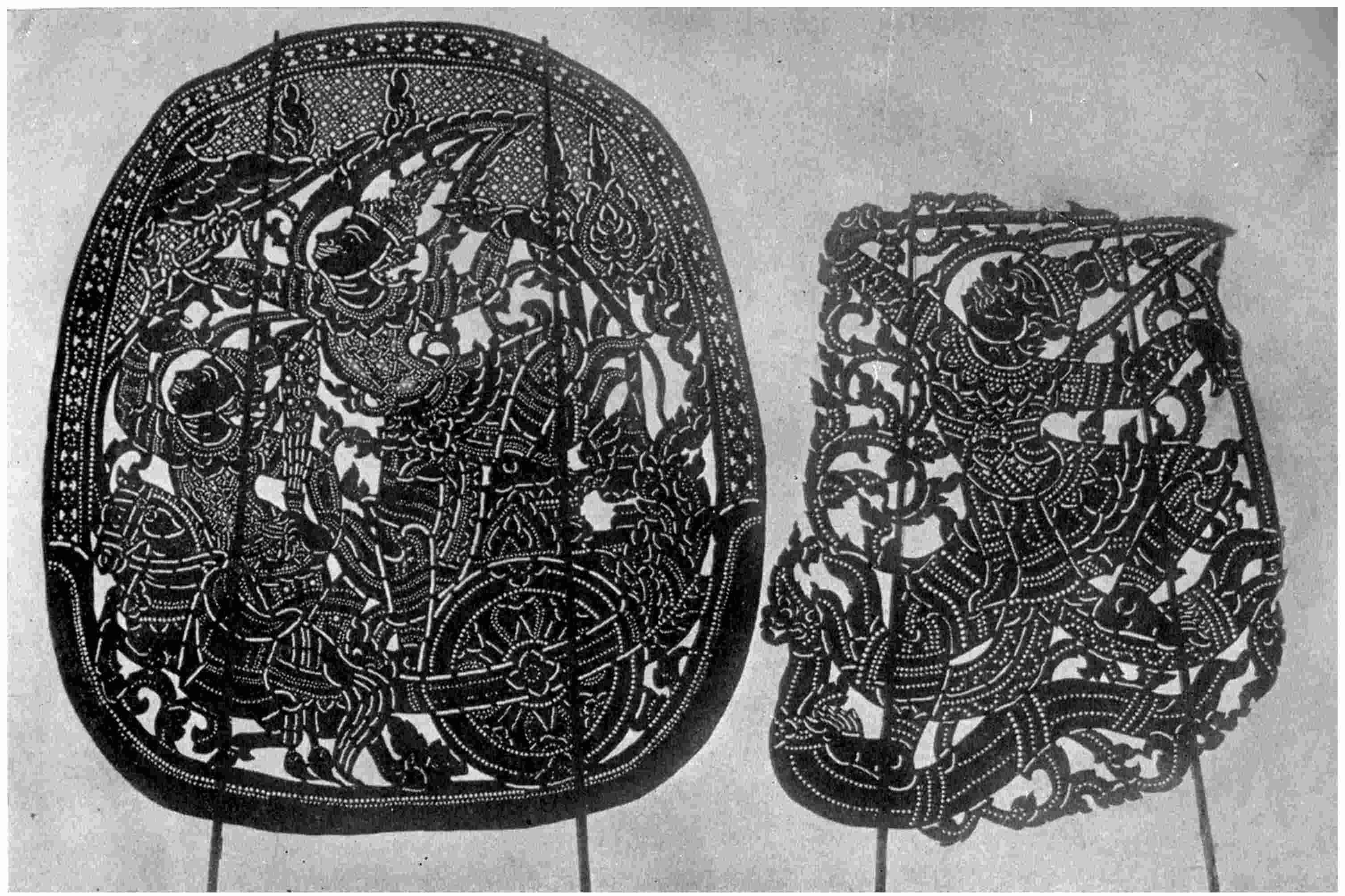

SIAMESE SHADOWS

Belonging to the collection in the Smithsonian Institution, U. S. National Museum. This collection was presented by the King of Siam in 1876

But not alone this. Excavators in the Catacombs have discovered small jointed puppets of ivory or wood in many tombs. They look like dolls, but they may have been religious images used by the earliest Christians. The Iconoclasts in their zeal annihilated everything that had the appearance of an idol, and many a puppet perished along with the images of the gods, Maccus as well as Apollo! But soon the Church saw the wisdom of using concrete, vivid representation instead of mere abstract symbolism scarcely comprehensible to the simple minded. “Into the churches crept figures, Jesus’ body on the Cross instead of the Lamb. To the Apollo of Heliopolis succeeded the crucifix of Nicodemus, to the Theban Venus the Madonna of Orihuela.” (P. Ferrigni.) Occasionally these figures were made to move a head or to gesticulate. And here we find the earliest beginnings of the mysteries which were later to come out from the churches and monasteries as precursors not only of our puppet shows but of practically all our drama.