Oriental Puppets

THERE are few of us who at times have not unleashed our imaginations, flung away the reins and bidden our thoughts roam freely beyond the vision of our straining eyes. Who has not pondered whimsically what sort of crooked creatures may be shambling over the craters and crevices of the moon? Similarly the unfamiliar Eastern lands afford adventure for our Western fancies. How alluring the imaginary sights and sounds fantastically flavored; glimmer of spangles, daggers, veils and turbans, camels and busy bazaars and mosques white in the sun, strumming of curious instruments, gurgle, clatter and patter, enigmatical whisperings and silences of unknown import. But of all things so strange what could be fashioned stranger than the puppets of Eastern peoples? As the dreams and philosophies of the Orient seem farther away from us than its most distant cities, so these small symbols of unfamiliar creeds and cultures for us are most amazing. What skill and artistry is displayed in the creation of them, what capricious imagery in their conception! Let us consider them.

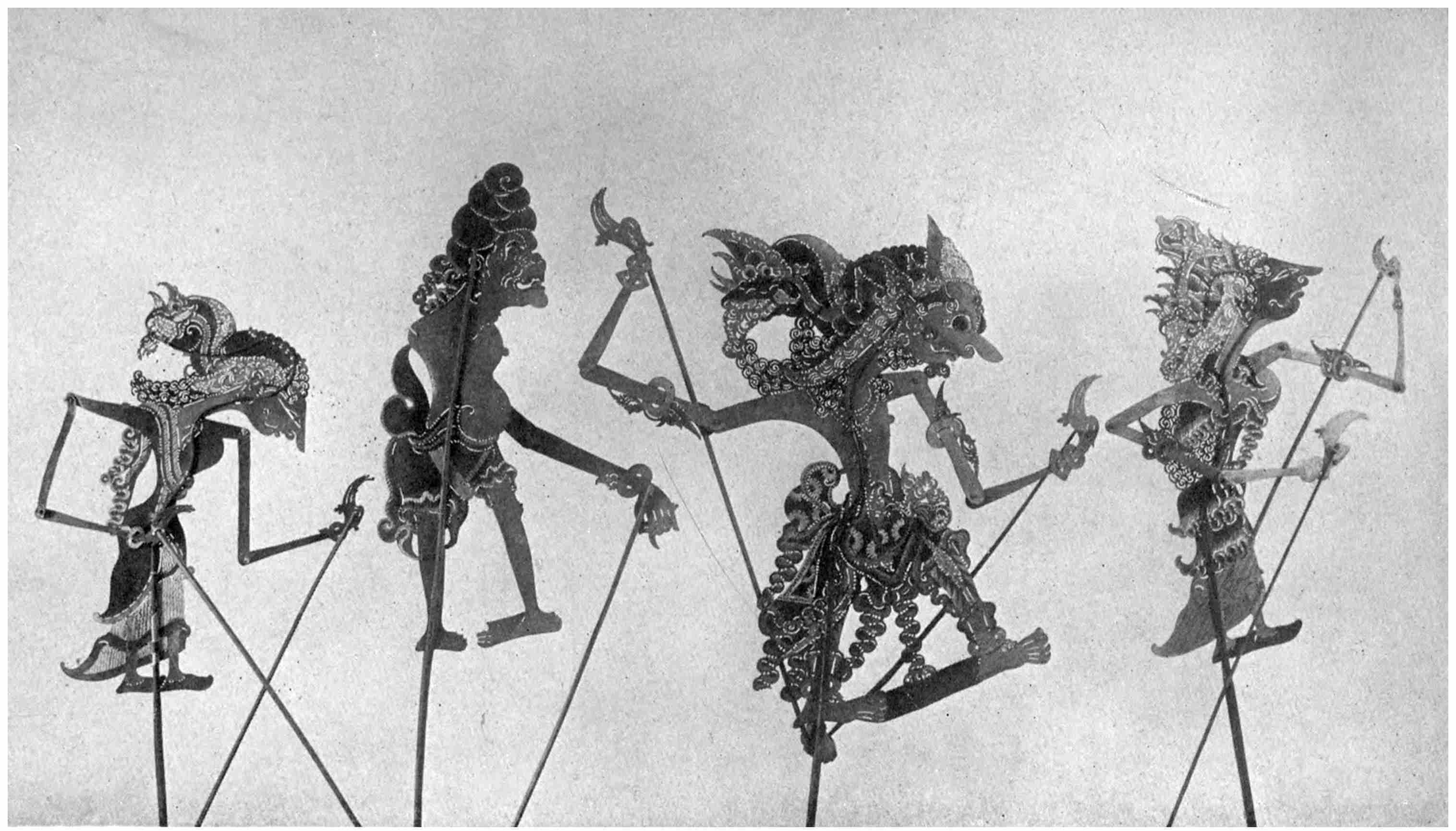

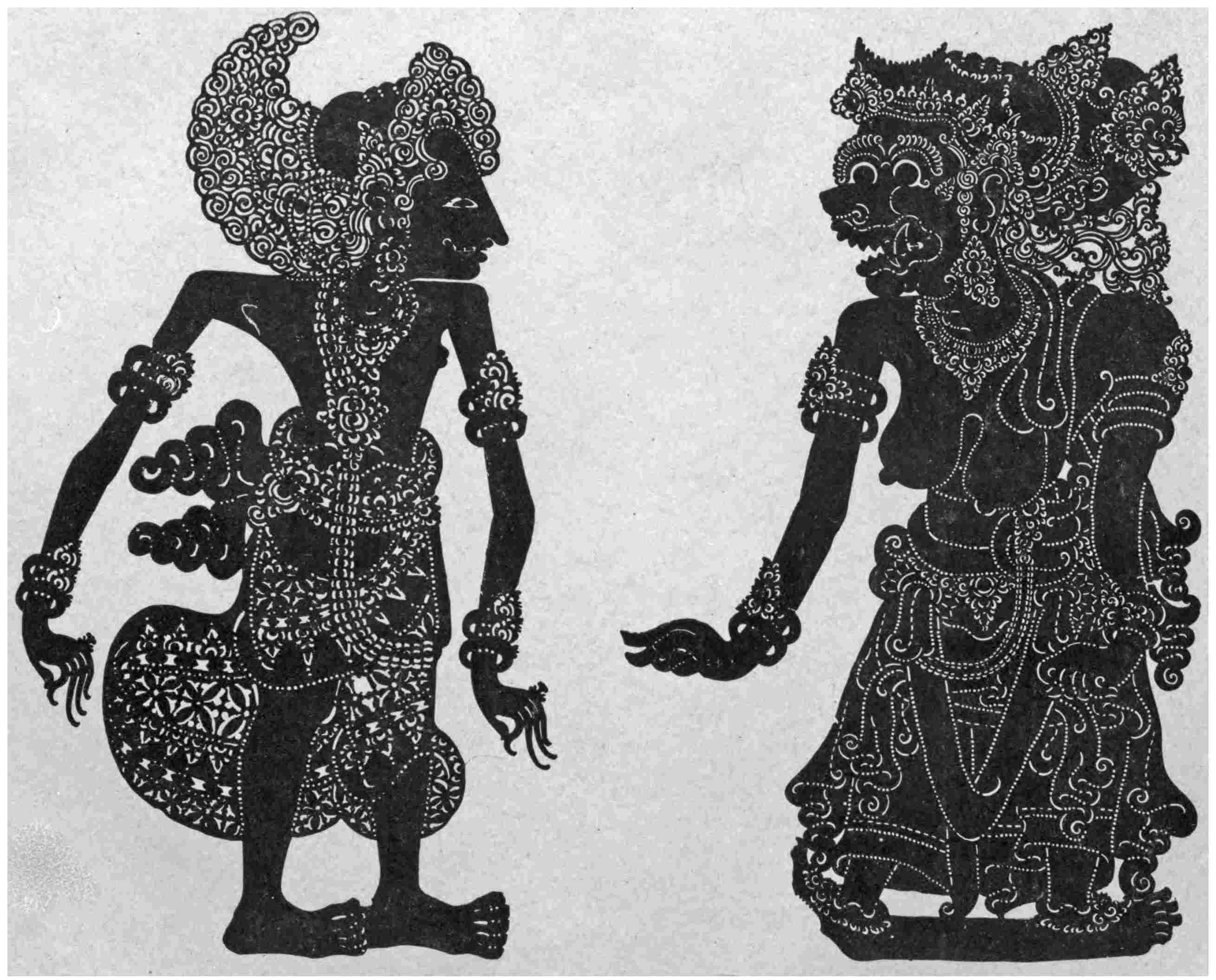

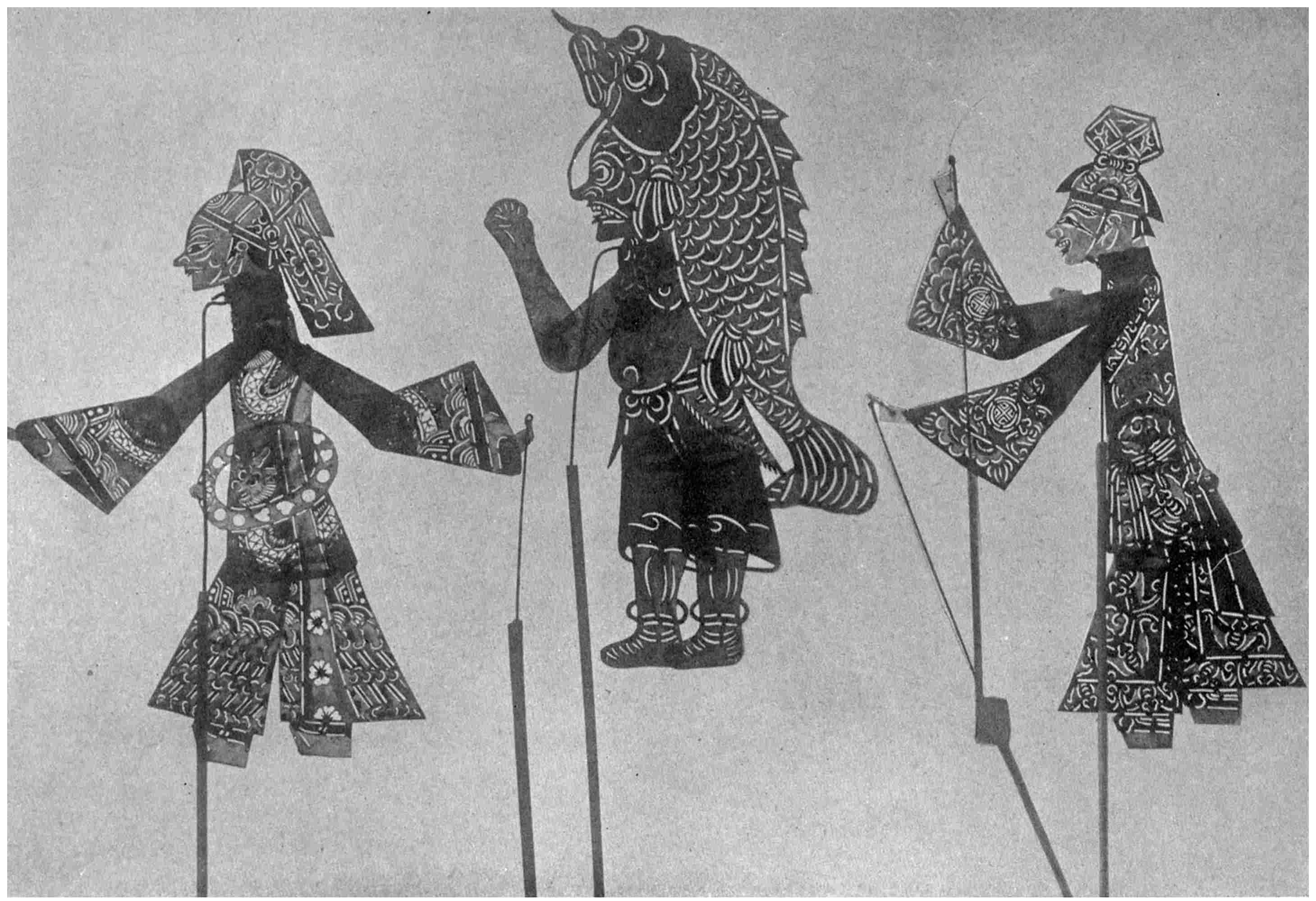

JAVANESE WAYANG FIGURES

[American Museum of Natural History, New York]

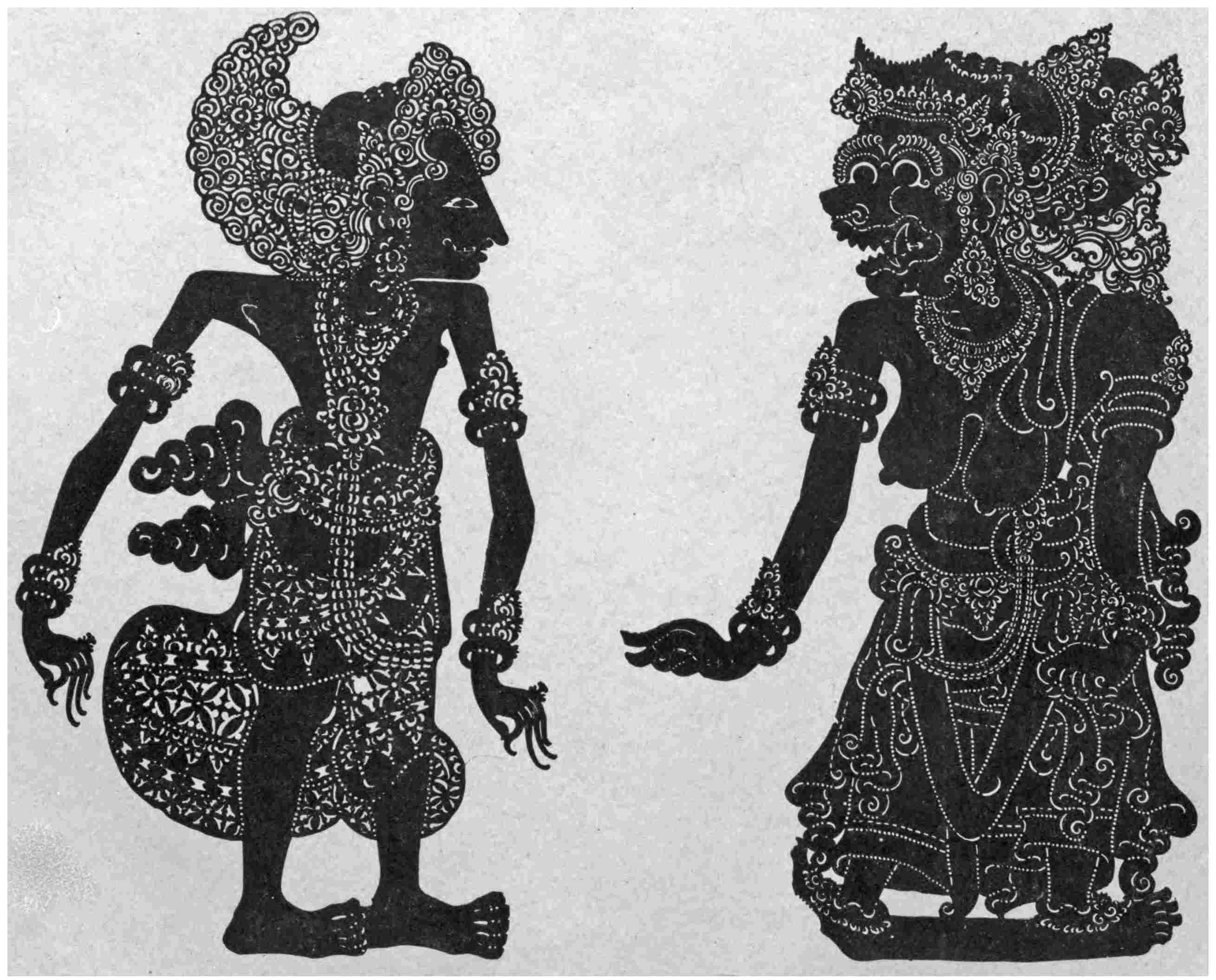

Probably the Javanese shadows present the most weirdly fascinating spectacle to our unaccustomed eyes. What singular creatures are here? Bizarre beyond all description, grotesque forms with long, lean beckoning arms and incredible profiles, adorned with curious, elaborate ornamentation. They are made of buffalo skin, carefully selected, ingeniously treated, intricately cut and chiseled, richly gilded and cunningly colored, and they are supported and manipulated by fragile and graceful rods of horn or bamboo. Such are the colorful and inscrutable little figures of gods and heroes in the Wayang Purwa, ancient and celebrated drama of Java, popular now as in the days of Java’s independence.

These shadow-plays are half mythical and religious, half heroic and national in character, portraying the well-known feats of native gods and princes, the battles of their royal armies, their miraculous and preposterous adventures with giants and other fabulous creatures. Each incident, each character is familiar to the audience. One heroine is thus described in Javanese poetry. “She was really a flower of song, the virgin in the house of Pati. She was petted by her father. Her well-proportioned figure was in perfect accord with her skill in working. She was acquainted with the secrets of literature. She used the Kawi speech fluently, as she had practised it from childhood. She was elegant in the recitation of formulas of belief and never neglected the five daily prayer hours. She was truly Godfearing. Moreover, she never forgot her batik work. She wove gilded passementerie and painted it with figures, etc., etc. She was truly queen of the accomplished, neat and charming in her manner, sweet and light in her gestures, etc., etc.

“She was sprayed with rosewater. Her body was warm and hot if not anointed every hour. She was the virgin in the house of Pati. Everyone who saw her loved her. She had only one fault. Later, when she married, she could not endure a rival mistress. She was jealous, etc.”

A prose account tells us of the same young lady. It is said of Kyahi Pati Logender’s youngest child: “This was a daughter called Andjasmara, beautiful of form. If one wished to do full justice to her appearance the describer would certainly grow weary before all of her beauty could be portrayed. She was charming, elegant, sweet, talkative, lovely, etc., etc. Happy he who should obtain her as a wife.”

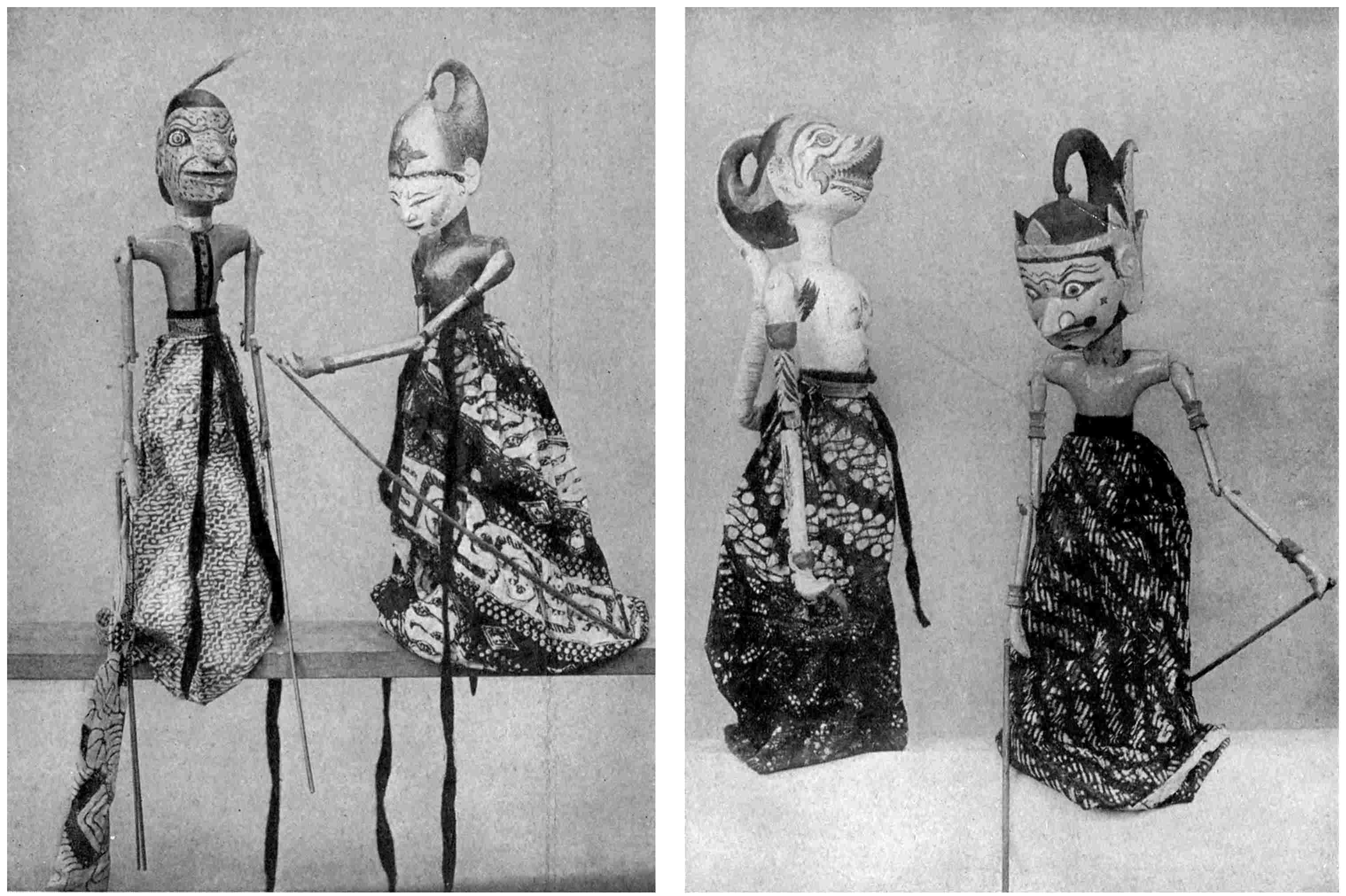

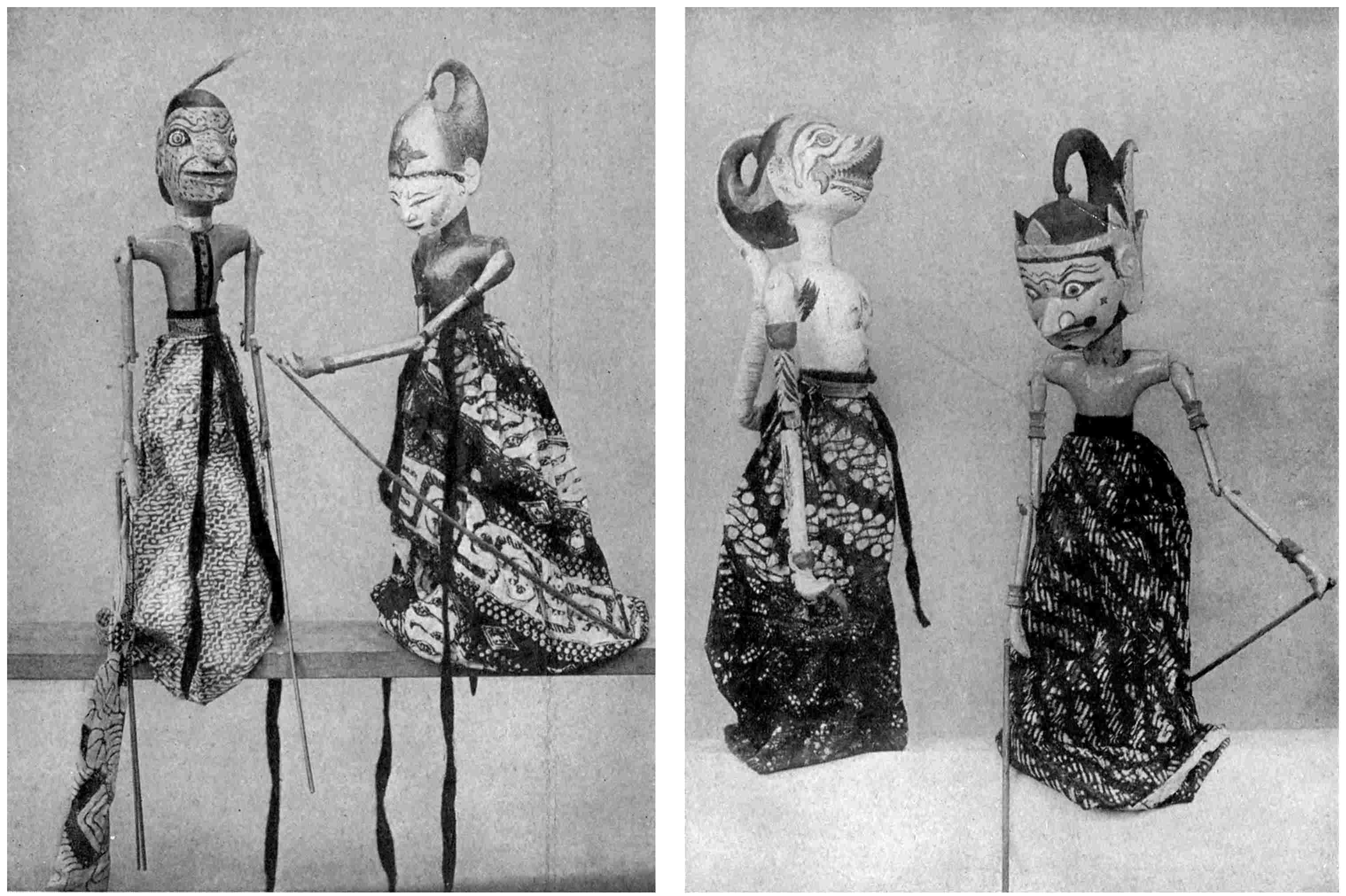

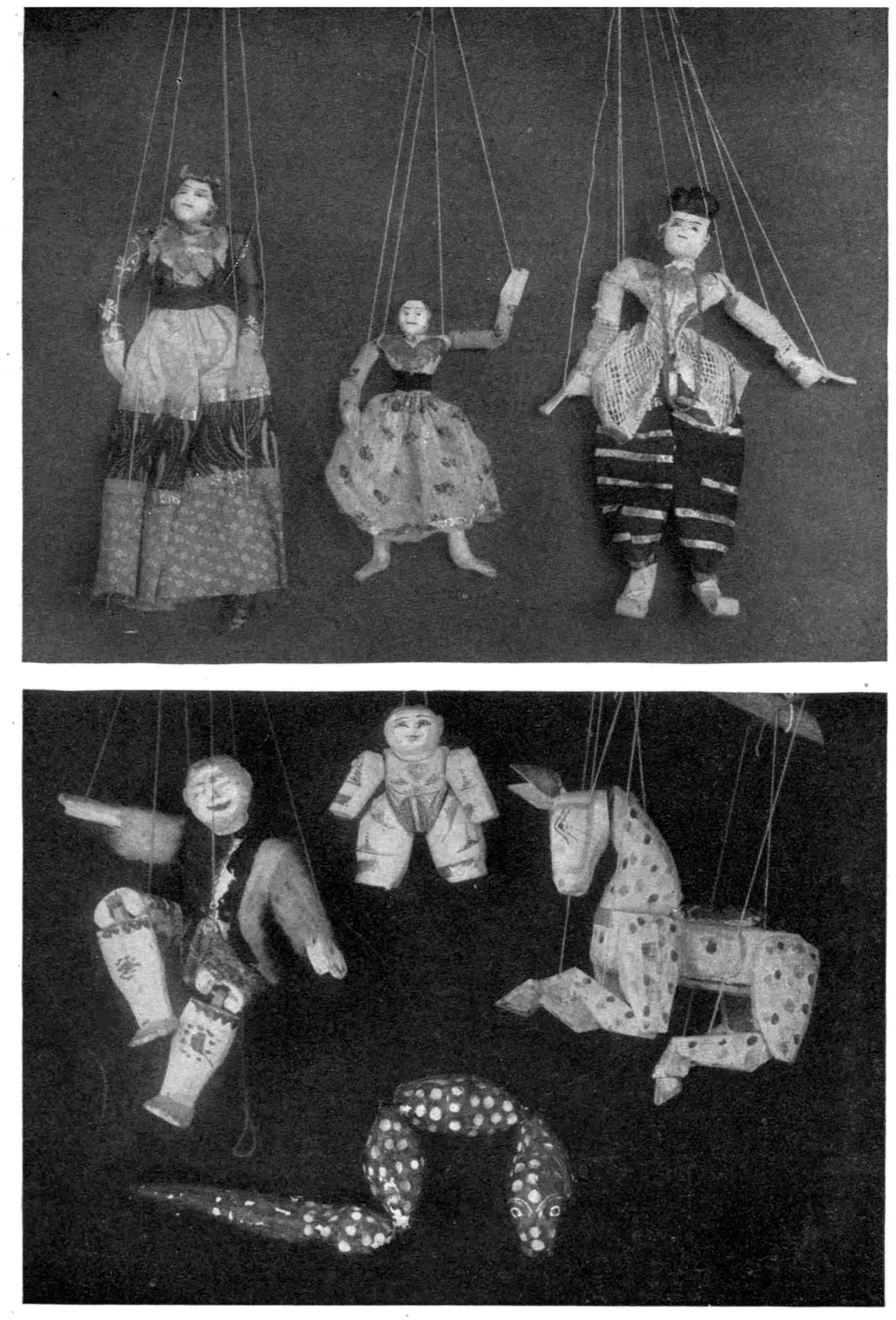

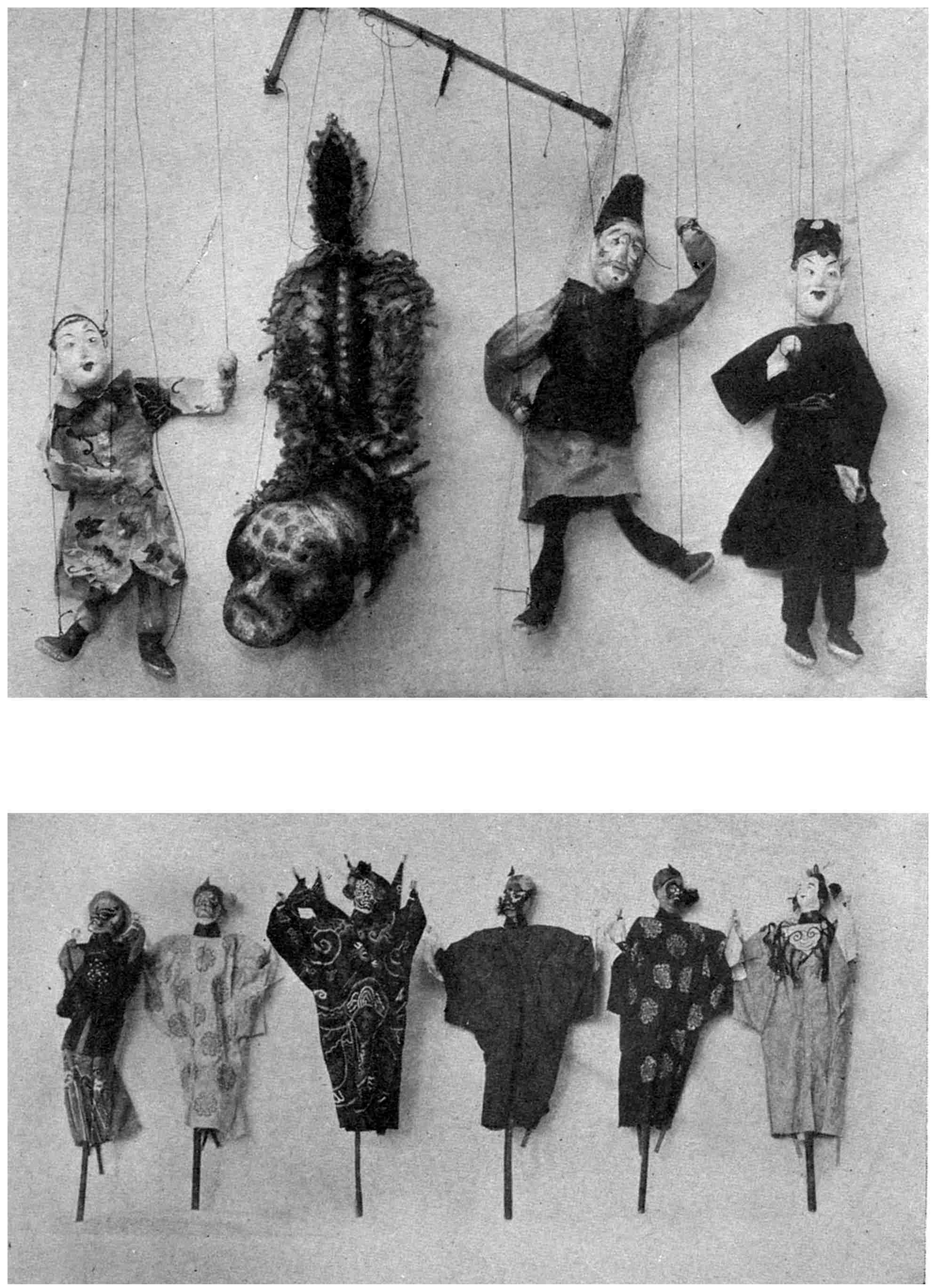

JAVANESE ROUNDED MARIONETTES

[American Museum of Natural History, New York]

The plots are based upon old, old Indian saga, from the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, the Pandji legends and also upon native fable such as the Manik Muja. There are several varieties of Wayang play, each founded upon one or several of these sources. The Wayang Purwa and the Wayang Gedog are silhouette plays presented by leather figures behind a lighted screen. Sometimes, however, the women in the audience are seated on one side of the screen, the men on the other, so that some see the gray shadows, others the colored figures. The Wayang Keletik is given not with shadows but with the painted hide figures themselves displayed to the audience. All these performances are not ordinary public events, but rather special productions in celebration of particular occasions. Etiquette at the Wayang demands that regular rites be observed before the performance, incense burned and food offered to the gods.

The Dalang, or showman, is a person of great skill and versatility. He seats himself cross-legged on a mat surrounded by figures; there are about one hundred and twenty to a complete Wayang set. He directs the gamelin music of the orchestra which keeps up a tomtom and scraping of catgut throughout, gives a short preliminary exposition of the plot, brings on the characters which he holds and manipulates with slender rods, places them with precision and then the play begins. The Dalang, as the music softens, speaks for each one of the characters. The general tone is heroic with comedy introduced upon occasion. There are struggles, battles, love scenes, dances. The Dalang shuffles with his feet for the dancing, makes a noise of tramping or fighting, adjusts the lights on the screen, all the while moving the figures and speaking feelingly for them.

Besides these so-called shadows the Javanese have also rounded marionettes carved out of wood, which have long, slender arms and fantastic touches revealing kinship with the figures of painted hide. The play presented by these crude but rather startling dolls is called Wayang Golek. The puppets are moved from below by rods attached to their bodies and hands as are the shadow figures. Still other types of plays are the Wayang Beber, presented by rolls of pictures, and much later (eighteenth century) the Wayang Topang in which rigidly trained human actors, dressed in the conventional costumes of the Wayang figures, take the parts of the puppets. But here as in the puppet dramas the Dalang reads all the words.

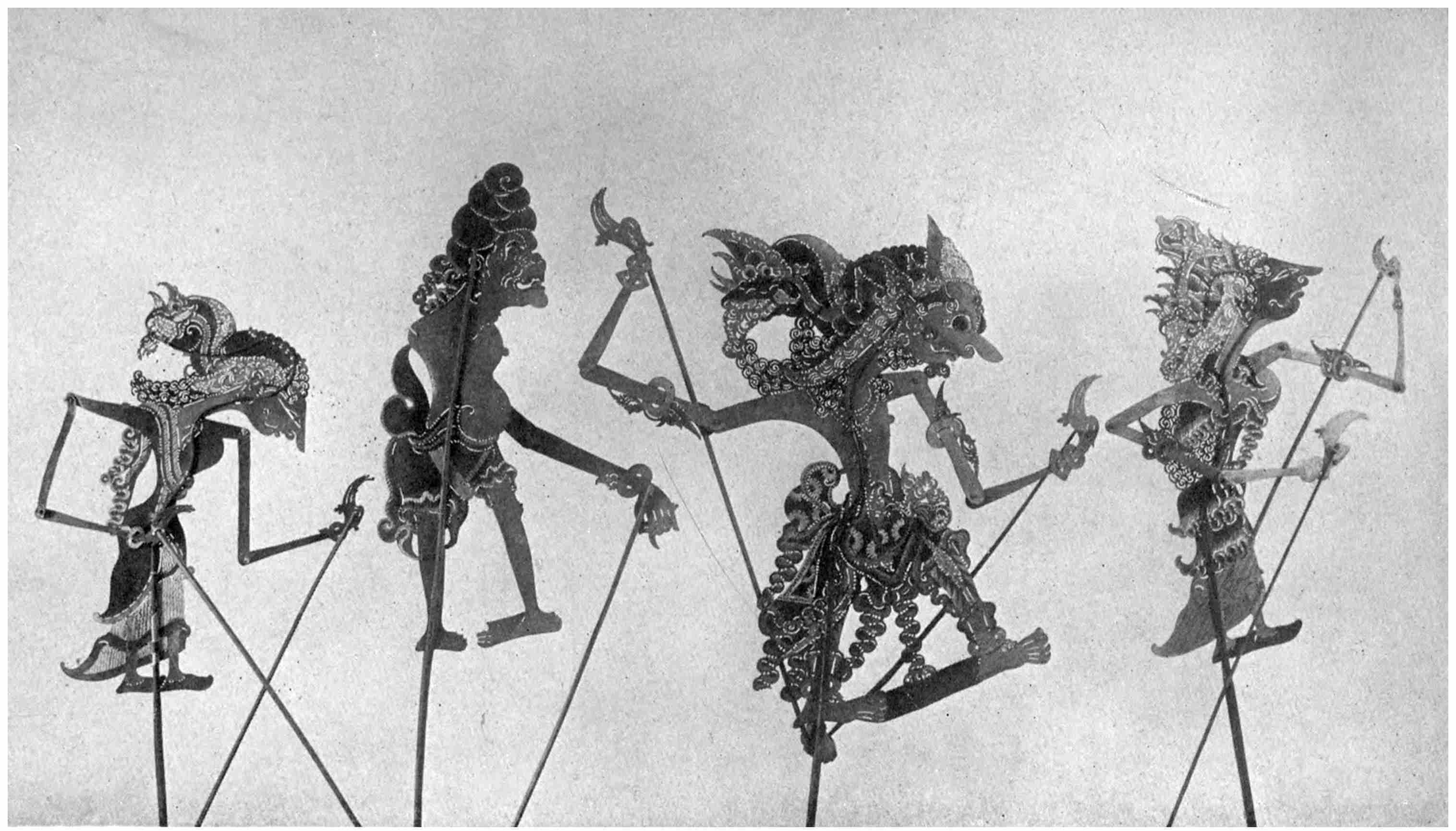

On the island of Bali, one of the group of the Indian Archipelago, Wayang plays are like those of Java. The old figures are very wonderful, cut out of young buffalo hide, carefully treated and prepared. The tool formerly used to make them was a primitive pointed knife. The Wayang sets made to-day, in spite of the superiority of modern European instruments which are employed, are very crude in comparison. This is because with the loss of independence the natives also lost all interest in their own art and culture; indeed new Wayangs are made only when the old ones are worn out.

* * * * *

The shadows of the Siamese Nang are also unusual. This is a representation of certain scenes from the Indian epic, Ramayana, and depicts the adventures of Prince Rama and his wife Sita. It is given in private homes for special festivals and is of a serious, poetic nature. As described by a native of Siam, “It is a show of moving, transparent pictures over a screen illumined by a strong bonfire behind.” It is recited by two readers and sometimes requires as many as twenty operators. The figures more nearly approach the human form than do those of the Javanese shadows, but their queer, pointed headdress and strange costuming produce a very striking and highly stylized effect. They are made of hide which has been previously cut, scraped and stretched with extreme care. The technique of decorating the figures is most difficult, for the forms are stenciled and perforated by an infinite number of pricks, to indicate not only the outlines but also the nature of the fabric of garments, the jewels, weapons, etc. These perforations scarcely show unless held before a light, when they give a very rich and variegated effect. There is great art as well in the dyeing and fixing of the colors, and in estimating the amount of light which should be allowed to penetrate so as to give a well-proportioned aspect to the figure as a whole. In Siam as in Java there are to be found ordinary dramatic performances by wooden puppets more recent in origin and not unlike those of Burma.

* * * * *

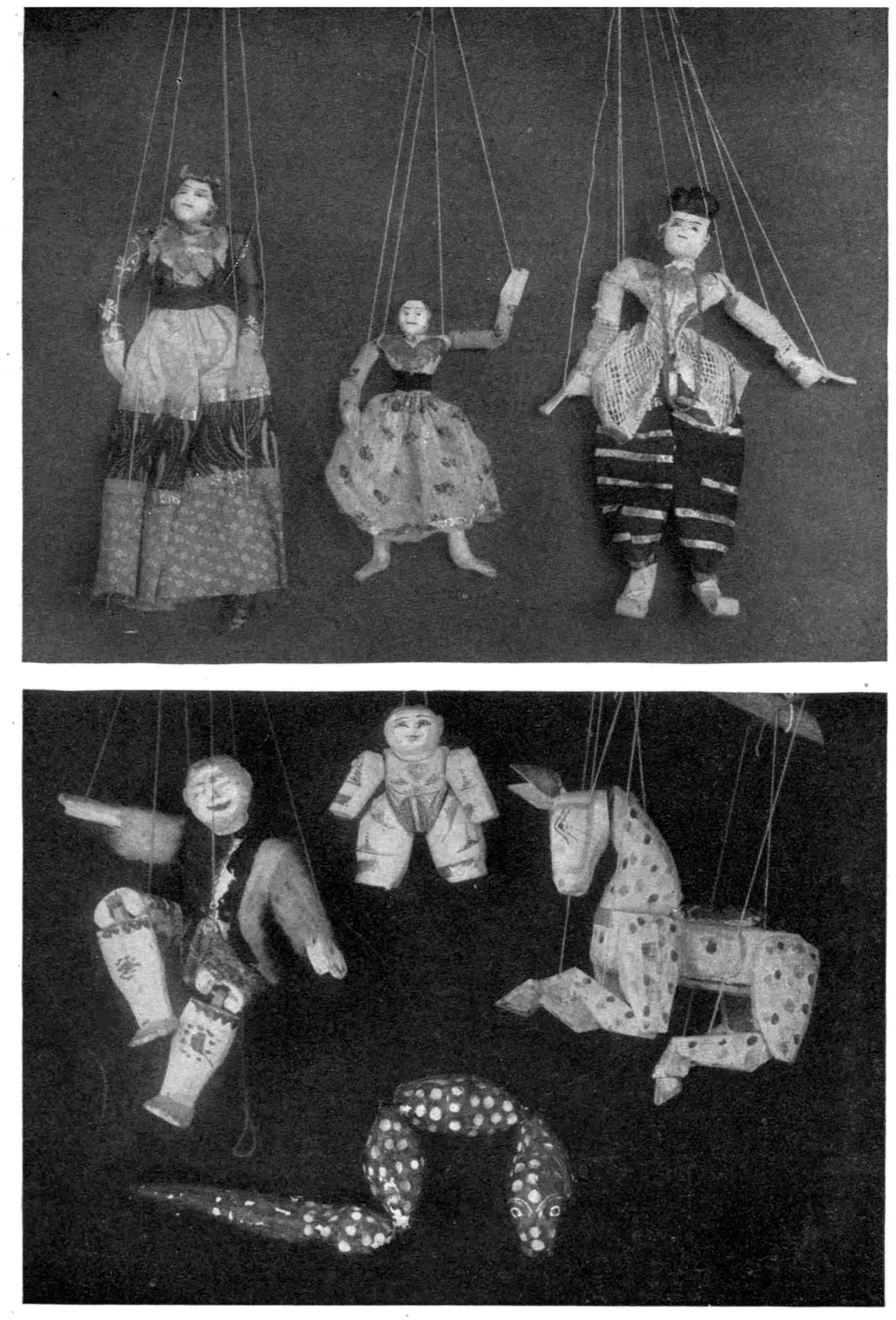

These puppet theatres of Burma exhibit a peculiar combination of fantastic legend and grotesque, realistic humor. The puppet stage of the country seems to have been more highly developed than its regular drama. A visiting company of Burmese marionettes was displayed at the Folies Bergères in Paris, where they were much admired for their beautiful costumes, wonderful technical construction, the natural poses they assumed and the graceful gestures they made. Mr. J. Arthur MacLean tells of the annual celebration which he witnessed a few years ago at Ananda, the famous old Buddhist site. It consisted of a performance by the temple puppets which began early in the evening and lasted all the night through. The marionettes were the property of the temple and when not in use were stored away there. They were large and elaborate and manipulated with strings. The audience comprised the entire population of the village; every man and woman was present and they had brought all of their children. The first part of the show was comical for the sake of the children who, we may presume, fell asleep as the night progressed. The plays which followed became more and more serious and were of a religious nature. Some Burmese puppets, however, are very primitive, being painted wooden dolls, odd and humorous in spirit. The license of the showman is extreme, but does not seem to offend the taste of the native audience.

* * * * *

In Turkestan and in Central Asia puppet shows are a very popular diversion along with the feats of jugglers and dancers. There are two types of puppets existing, one the very diminutive dolls carried about by ambulant players whose extremely naïve dialogue is composed chiefly for the amusement of children. The other, on a larger scale, is to be seen on small stages erected in coffee houses or at weddings and other private celebrations.

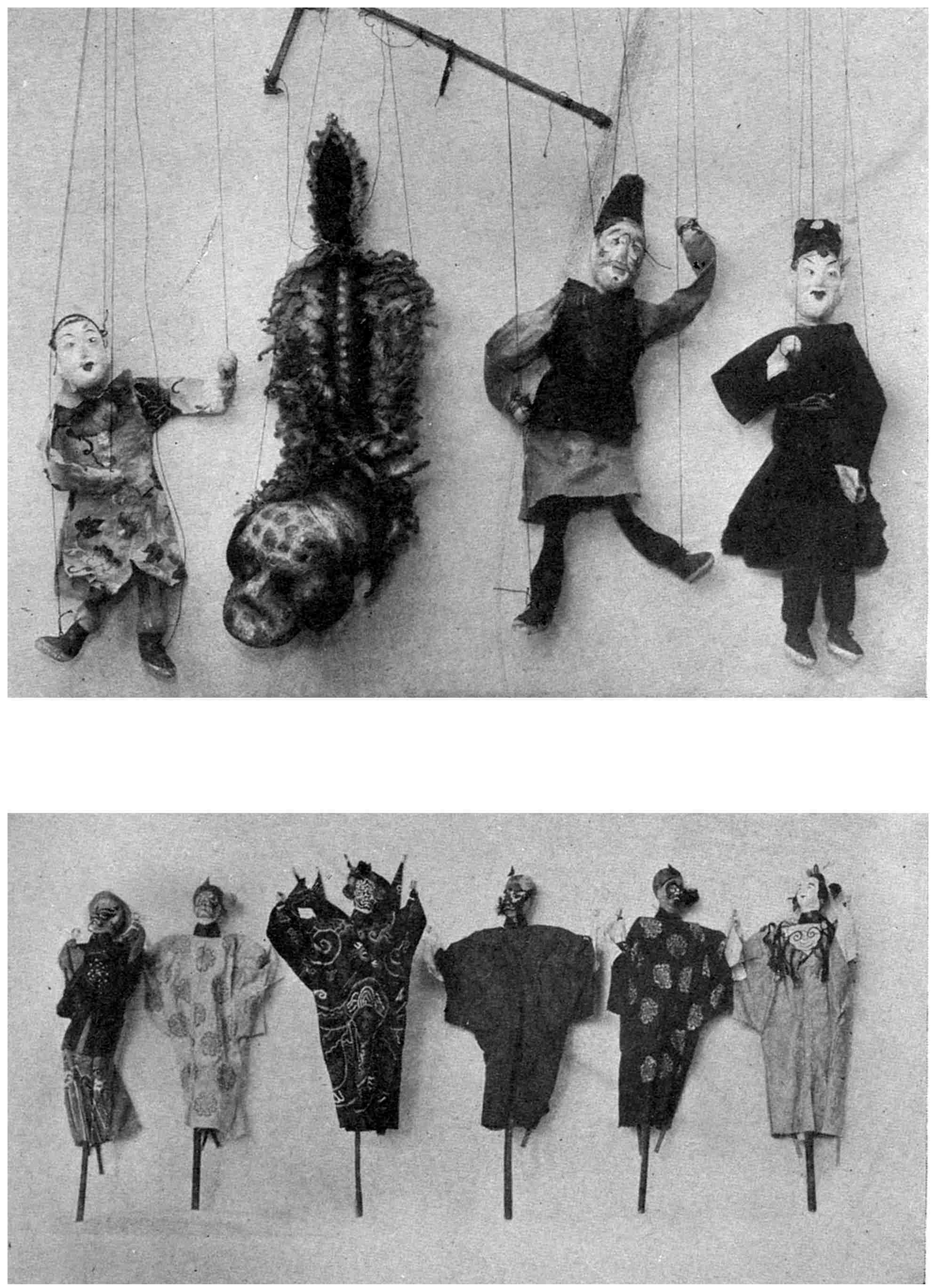

BURMESE PUPPETS

Upper: Made of rag, cotton and plaster

Lower: Made of painted wood

[American Museum of Natural History, New York]

R. S. Rehm gives a description of a crude little marionette theatre in Samarkand. Out in the crowded narrow streets sounds as terrifying as the trumpet on the walls of Jericho announced the beginning of the performance. The interior was a dark hall with a roof of straw matting through the holes of which mischievous youngsters were continually peeking until they were chased away. It was called Tschadar Chajal, Tent of Fantasy. The puppets revealed Indian origin, but their huge heads, with the clothing merely hung upon them, indicated Russian influences. There was one scene of modern warfare with toy cannons hauled upon the stage. Then came a play within a play. Yassaul, the native buffoon, was a sort of master of ceremonies. Various comical and grotesque marionettes appeared whom he greeted and led to their places. The King himself entered upon a miniature horse, dismounted and seated himself on a throne in the tiny audience. The performance for His Majesty consisted of puppet dancers, puppet jugglers and last of all, a marionette representing a drunken European dragged away by a native policeman. At this point the small and also the large audience expressed great delight.

* * * * *

Of the puppets of Persia a very ancient legend tells us how a Chinese shadow play was performed before Ogotai, successor of Tamerlane. The artist presented upon his screen the figure of a turbaned old man being dragged along tied to the tail of a horse. When Ogotai inquired what this might signify the showman is said to have replied: “It is one of the rebellious Mohammedans whom the soldiers are bringing in from the cities in this manner.” Whereupon Ogotai, instead of being angry at the taunt, had his Persian art treasures, jewels and rich brocades brought forth, also rare Chinese fabrics and carven stones. Displaying them all to the showman, he pointed out the beauties in the products of both lands as well as the natural difference between them. The showman having learned this lesson of tolerance went away greatly abashed.

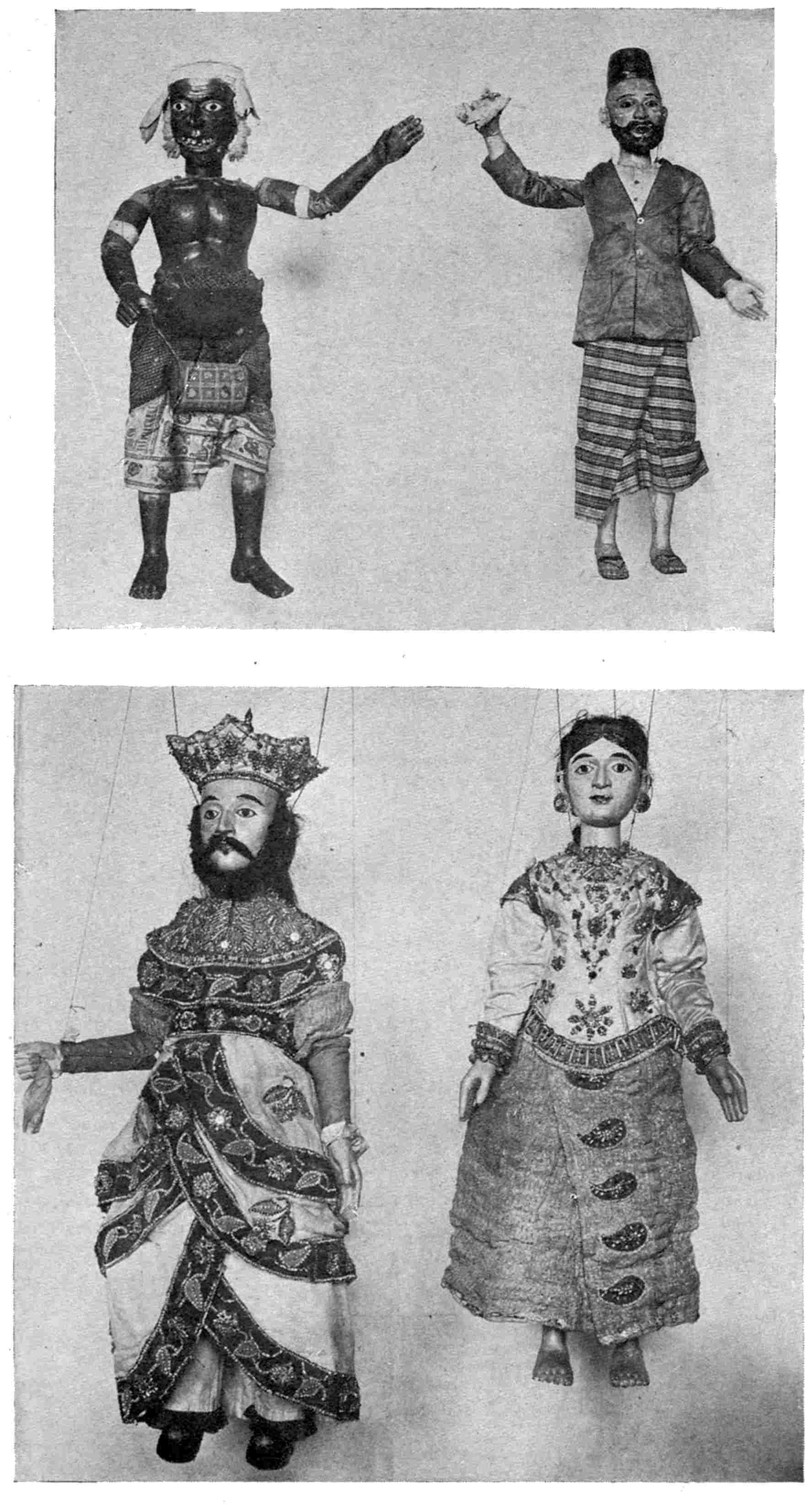

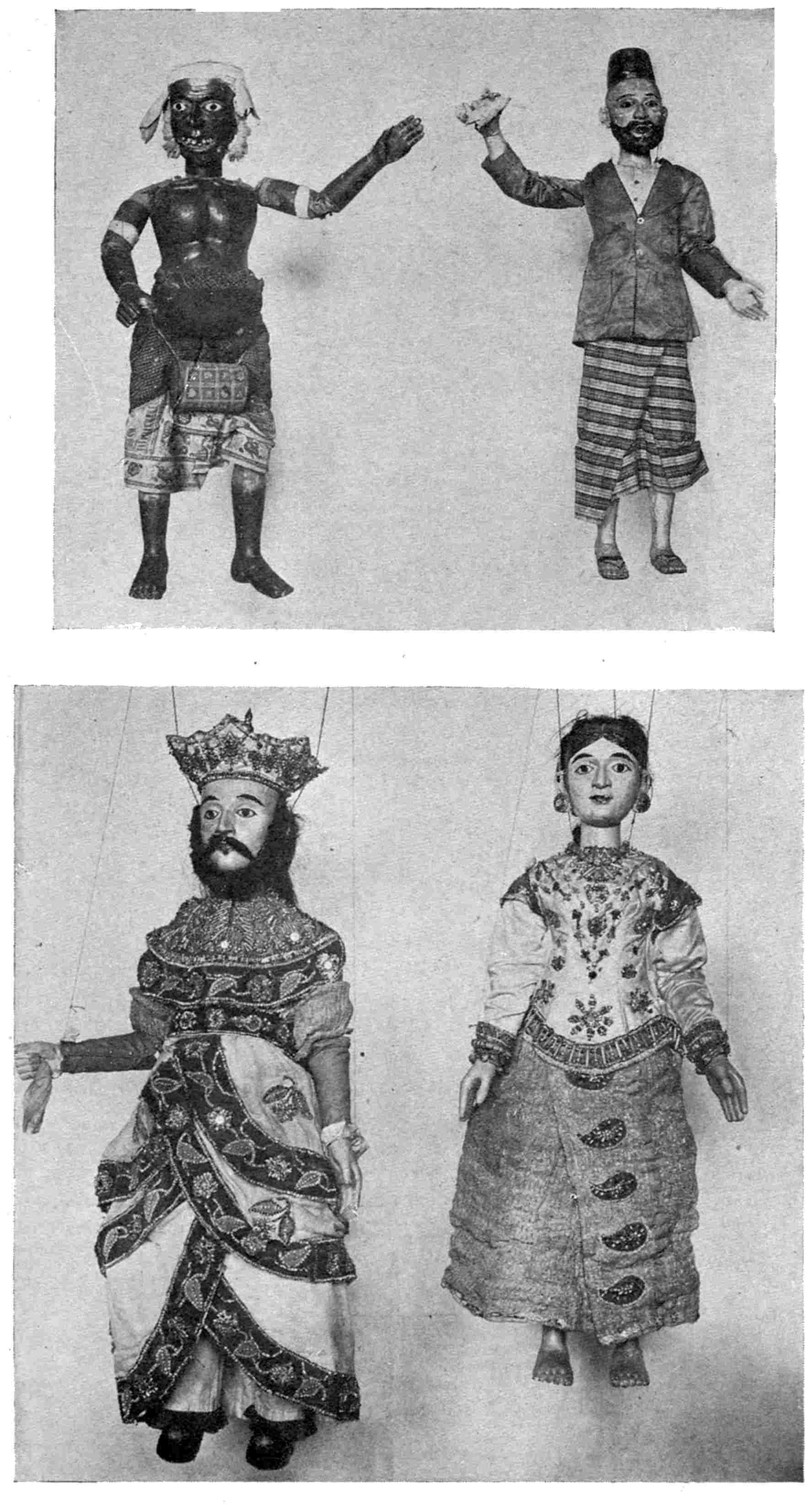

CINGALESE PUPPETS

Upper: Devil and Merchant

Lower: King and Queen

Part of a collection received from the Ceylon Commission of the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1895, by the Smithsonian Institution. U.S. National Museum

Shadows are mentioned in the works of the Persian poet, Muhammed Assar, in 1385, when they seem to have been eagerly cultivated. Since then, however, they have sadly deteriorated. It is said that wandering jugglers with their primitive dolls scarcely elicit a smile from the educated Persians, although they are sometimes asked into homes to amuse guests or children. As a rule they play in open places and after the show the owner collects the pennies from the audience standing around, calling down the curse of Allah upon those who walk away without paying. The comic puppet, according to Karl Friederich Flögel, is Ketschel, a bald-headed hero “more cultured than all the Hanswursts in the world.” He spouts poetry, quotes from the Koran, sings of the houris in Paradise and, when alone, throws aside his wisdom, dances and gets drunk.

* * * * *

Professor Pischel has written that he believes the puppet plays of India not only to have antedated the regular drama, but also to have outlived it. He claims moreover that the puppet shows are the only form of dramatic expression left at the present time. What a contribution from the marionette to the land of its birth and, on the other hand, how much the races of India must have given of themselves and their imaginations to the little wooden creatures; for the interest of the beholder, alone, is the breath of life which animates them through the centuries.

It is amusing to read of the life-sized walking and talking puppets used in the tenth century by a dramatist, Rajah Gekhara. One doll represented Sita and another her sister. A starling trained to speak Prakrit was placed in the mouth of Sita to speak for her. The puppet player spoke for the other doll as well as for the demon, which part in the drama he himself enacted and spoke in Sanskrit.2 In one of the issues of The Mask there is printed the following account of religious puppets of the thirteenth century in Ceylon. A great festival was being solemnized in the temple, which had been richly decorated for the event and furnished “with numerous images of Brahma dancing with parasols in their hands that were moved by instruments; with moving images of gods of divers forms that went to and fro with their joined hands raised in adoration; with moving figures of horses prancing; ... with likenesses of great elephants ... with these and divers other shows did he make the temple exceeding attractive.” (Mahavamsa, ch. 85).

In quite recent days, P. C. Jinavaravamsa, himself a priest and prince of Siam, as well as an artist, has written an article attesting the aesthetic worth and popularity of Indian puppets to-day. “Beautiful figures, six to eight inches high, representing the characters of the Indian drama, Ramayana, are made for exhibition at royal entertainments. They are perfect pieces of mechanism; their very fingers can be made to grasp an object and they can be made to assume postures expressive of any action or emotion described in poetry; this is done by pulling strings which hang down within the clothing or within a small tube attached to the lower part of the figure, with a ring or a loop attached to each, for inserting the fingers of the showman. The movements are perfectly timed to the music and recitation of singing. One cannot help being charmed by these Lilliputs, whose dresses are so gorgeous and jeweled with the minutest detail. Little embroidered jackets and other pieces of dress, representing magnificent robes of a Deva or Yakha, are complete in the smallest particular; the miniature jewels are sometimes made of real gold and gems.”

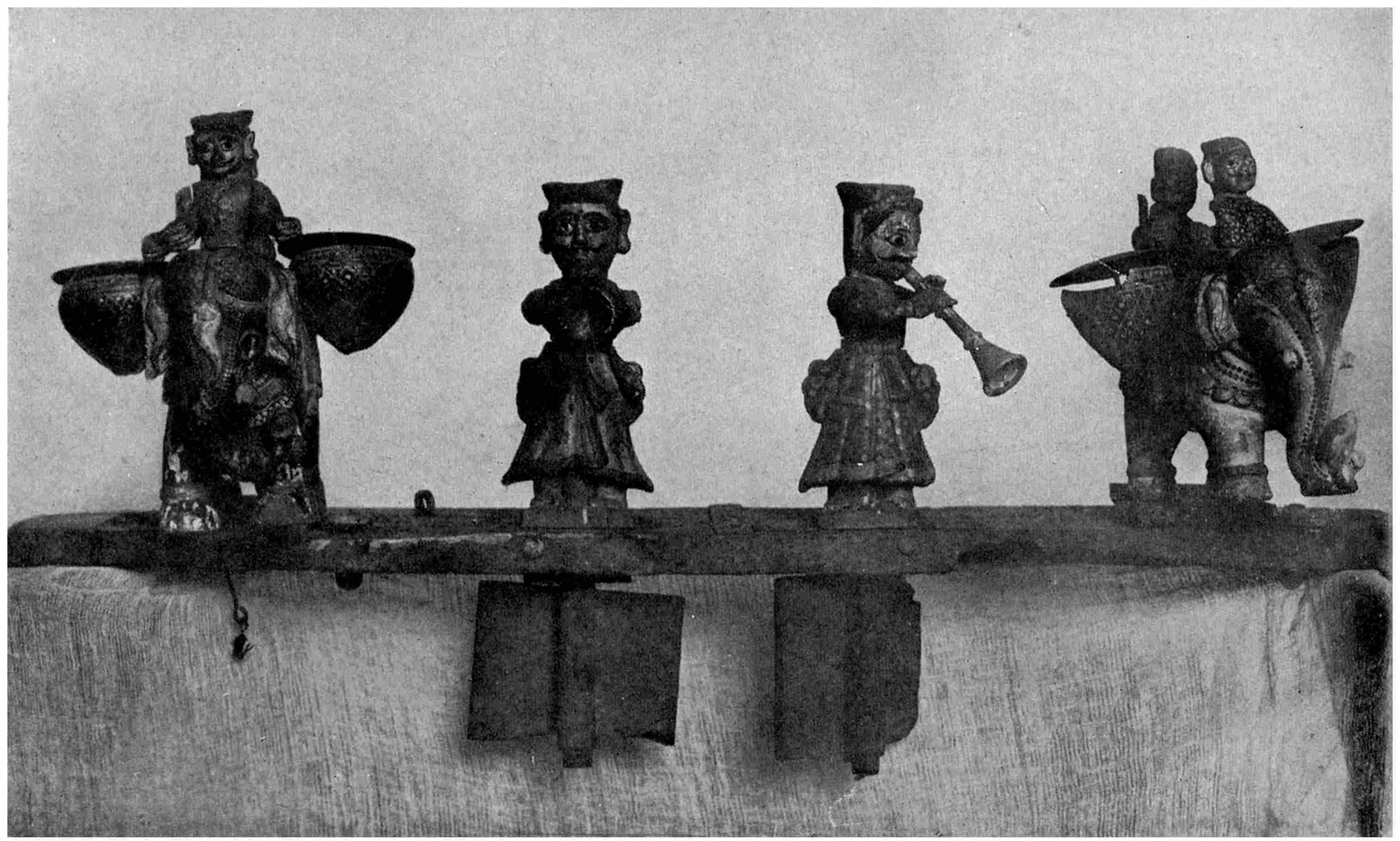

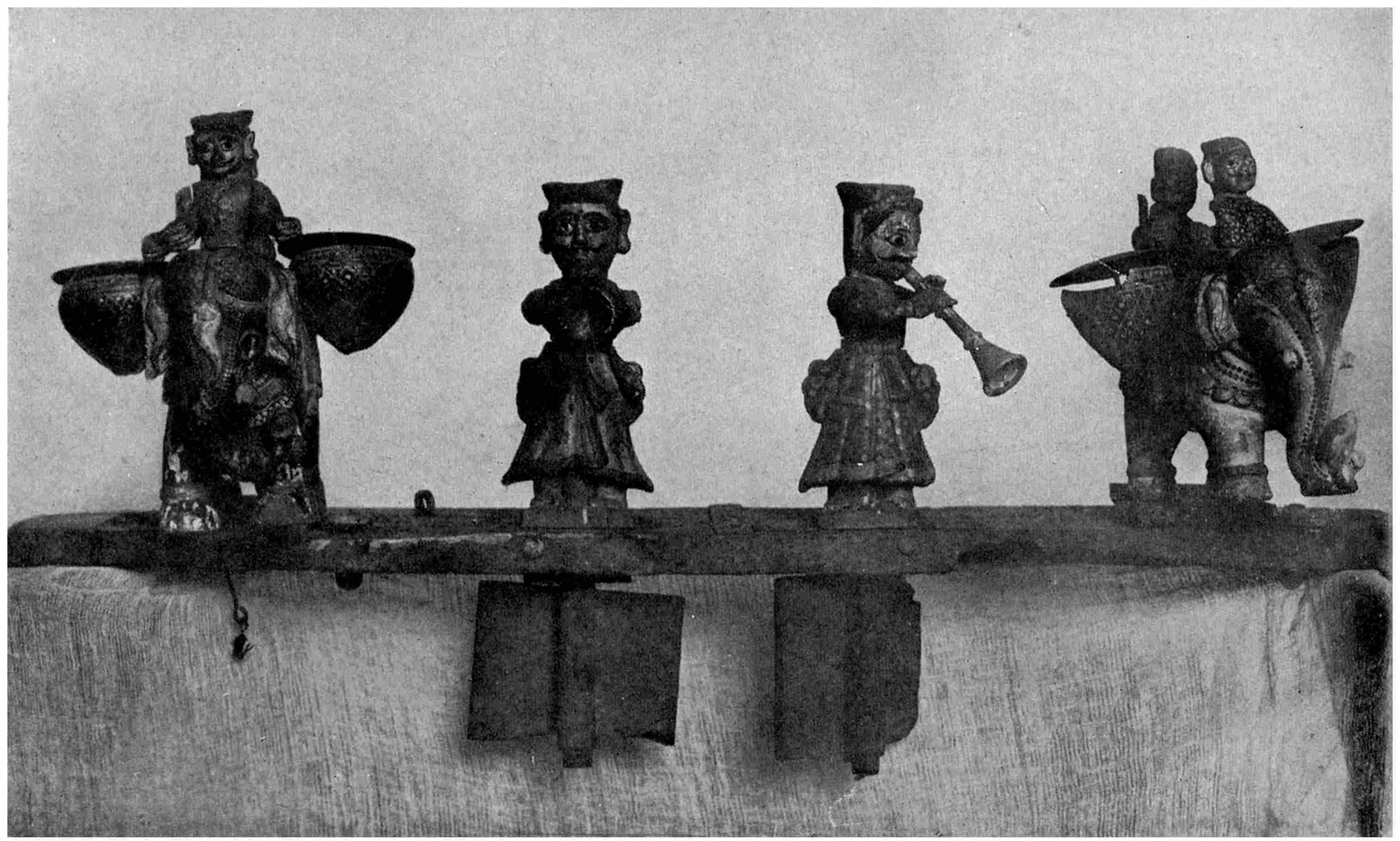

EAST INDIAN PUPPETS

From an old rest house for pilgrims connected with an old Jain Temple at Ahmadabad. The figures were attached to a mechanical organ and their motions followed the music

[Part of a collection in the Brooklyn Institute Museum]

The popular plays of India have never been written down, as were the classic dramas, but, according to the custom of wandering showmen, they were handed on from father to son. Thus, much in them has been lost for us. But Vidusaka, the buffoon, has survived, “as old as the oldest Indian art,” the fundamental type of comic character, and possibly the prototype of them all,—Vidusaka, a hunchbacked dwarf with protruding teeth, a Brahmin with a bald head and distorted visage. He excites merriment by his acts, his dress, his figure and his speech. He is quarrelsome, gluttonous, stupid, vain, cowardly, insolent and pugnacious, “always ready to lay about him with a stick.” Professor Pischel avers that we can follow this little comedian as he wandered away with the gypsy showmen whose original home was that of the marionette, mysterious ancient India. He trails him into Turkey, where he became metamorphosed into the famous (or infamous) Karagheuz after having served as a model for the buffoons of Persia, Arabia and Egypt. But more than this, it is believed that long before Arlecchino and other offspring of Maccus found their way northward there existed in the mystery and carnival plays of Germany a funny fellow with all the family traits of the descendants of the Indian Vidusaka. And it was probably the gypsies again, coming up from Persia and Turkey through the Balkan countries and Hungary (where similar types of puppet-clowns are to be discovered) who carried the cult from far-off times and introduced into Austria and Germany the ancient ancestor of Hanswurst and Kasperle.

* * * * *

In Turkey, as in so many Oriental countries, the shadow play is the chief representative of dramatic art. There are several little tales told concerning the origin of Turkish puppets. One relates how a Sultan, long ago, commanded his Vizier on pain of death to bring back to life two favorite court fools whom he had executed, perhaps somewhat rashly. The Vizier, in this dire dilemma, consulted with a wise Dervish, who thereupon caught two fish, skinned them and cut out of the dried skins two figures representing the two dead jesters. These he displayed to the Sultan behind a lighted curtain, and the illusion seems to have satisfied that autocratic personage.

Another story tells that long ago in Stamboul there lived a good man who grieved daily with righteous indignation over the misrule of the governing Pashas. He pondered long how to improve conditions and how to carry the matter to the attention of the Sultan himself. Finally he decided to establish a shadow play whose fame, he hoped, might lure the Sultan in to see it. And, indeed, the people thronged to witness his Karagheuz. But when at last the august Sultan came and took his place in the audience, Karagheuz had more serious matters to display than his usual pranks. The Sultan’s eyes were opened to the abuses of his ministers, whom he removed and justly punished. The founder of the Karagheuz play, on the other hand, was made Vizier. His show has remained the favorite diversion of the people.

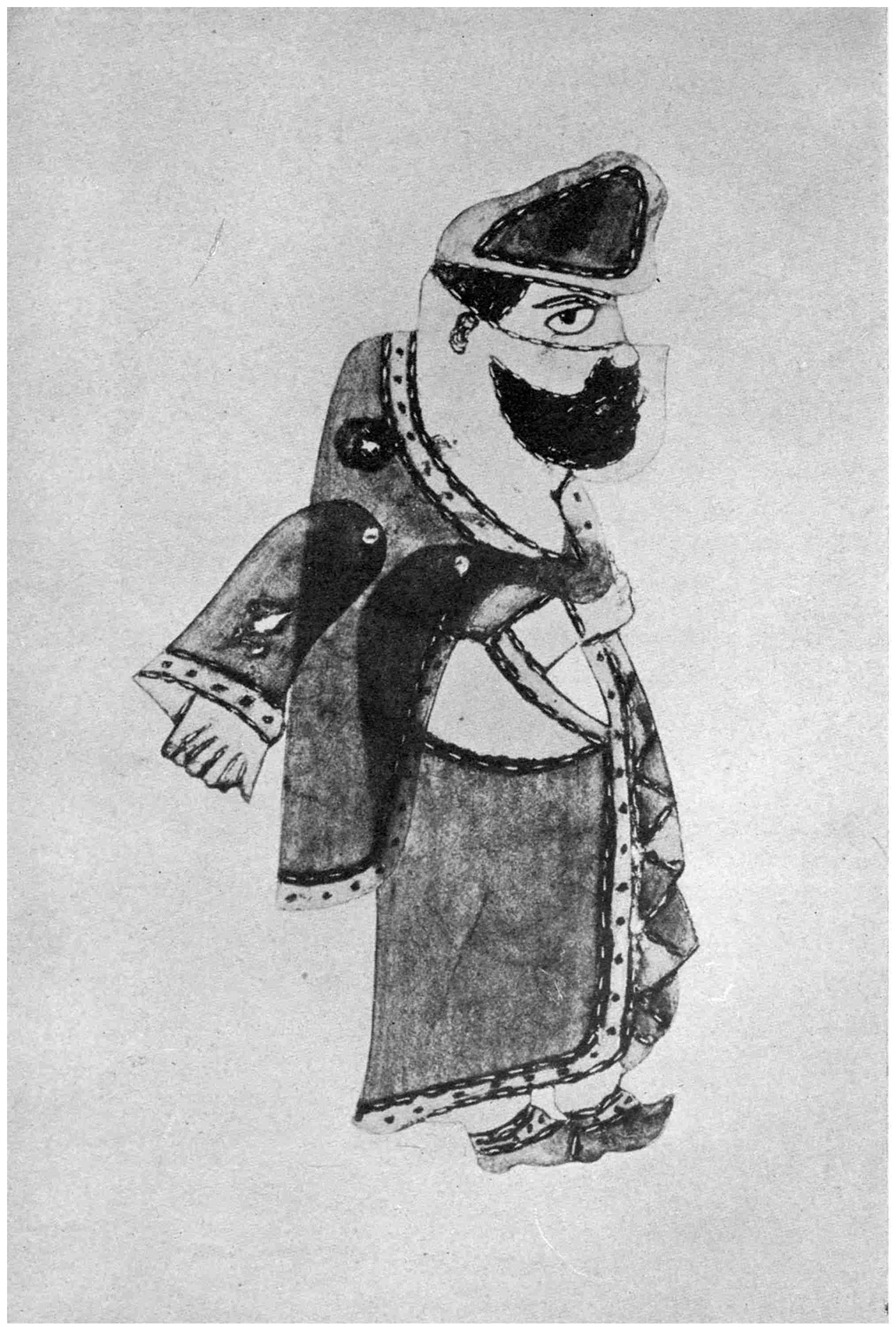

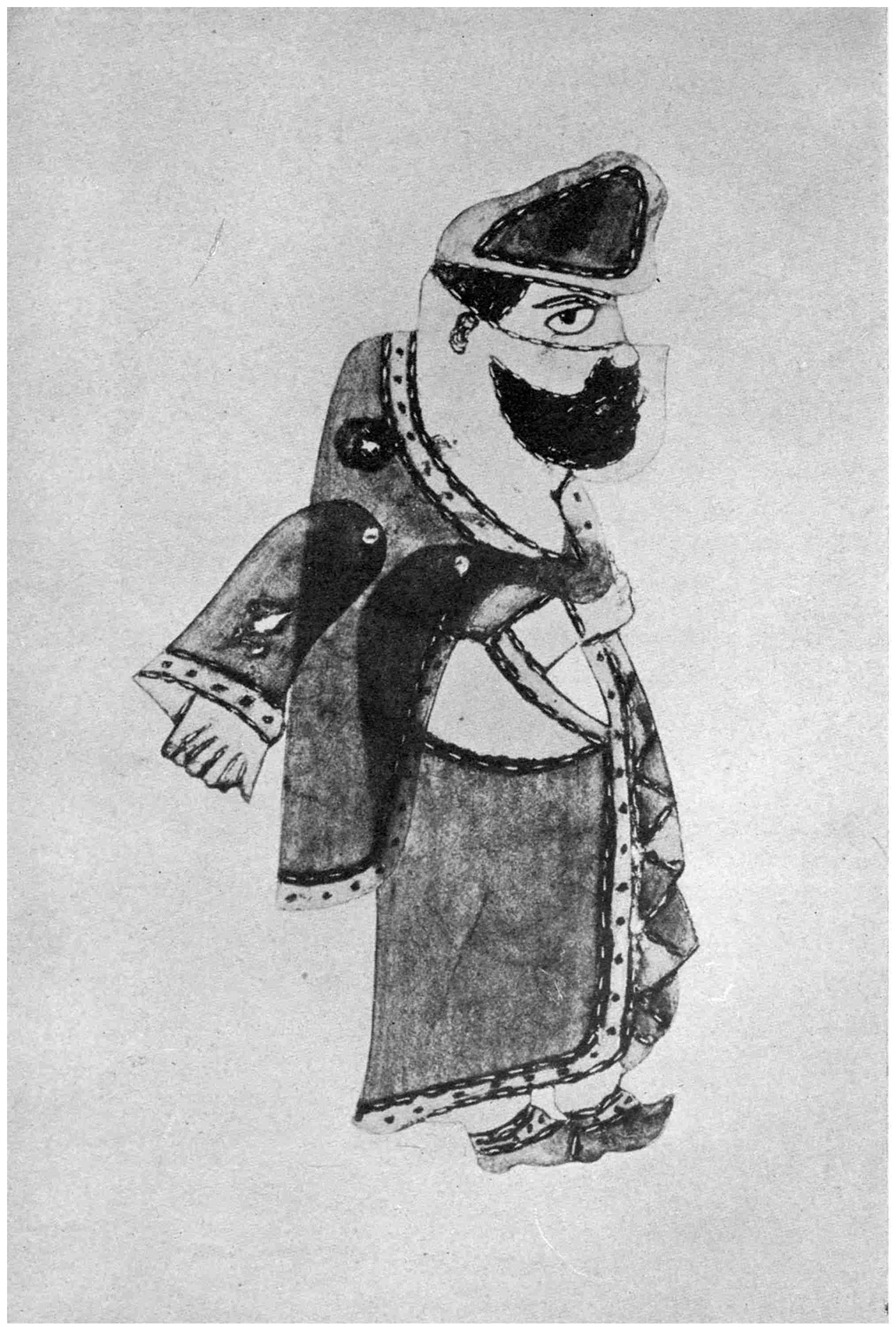

TURKISH SHADOW FIGURE OF KARAGHEUZ

[From Georg Jacob’s Das Schattentheater]

These Turkish shadows are all centered around the hero, a sort of native Don Juan, a scamp with a good bit of mother wit; he is called “Karagheuz” (Black Eye). There are about sixty other characters to a complete cast, among them Hadji-aivat, representative of the cultured classes and boon companion of Karagheuz, and Bekri Mustafa, the rich peasant just come to town, who frequents questionable resorts, gets drunk and is invariably plundered. There are Kawassan, the rich Jew, and a Dervish and a romantic robber and the Frank and the wife and daughter of Hadji-aivat and all sorts of dancers, beggar-women, etc. George Jacob brings to notice also pathological types such as the dwarf, the opium fiend, the stutterer and others; also representatives of foreign nations, the Arabian, the Persian, the Armenian, the Jew, the Greek, all of whose peculiar accents and mistakes in speaking the Turkish language form a constant source of merriment to the Turks themselves. The plot generally consists of the improper adventures of Karagheuz, his tricks to secure money, his surprising indecencies, his broad, satirical comment on the life about him. Théophile Gautier was present at a Karagheuz performance. He writes: “It is impossible to give in our language the least idea of these huge jests, these hyperbolical, broad jokes which necessitate to render them the dictionary of Rabelais, of Beroalde of Eutrapel flanked by the vulgar catechism of Vade.”

The extreme beauty of the production, however, and the expertness of the manipulator somewhat redeem the performances for our Western eyes. The figures are cut out of camelskin, the limbs skilfully articulated. Holes in the necks or chests and, for special figures which gesticulate, also in the hands, enable slender rods to be inserted at right angles by which they are manipulated. The appearance of the transparent, brightly colored figures, with heavy exaggerated outlines, rather resembles mosaic work, while the faces are sometimes done with the extreme care of portraits. The effect produced by these luminous forms is truly beautiful; the color is heightened by surrounding darkness, which tends to increase the seeming size of the figures and to give them an almost plastic quality.

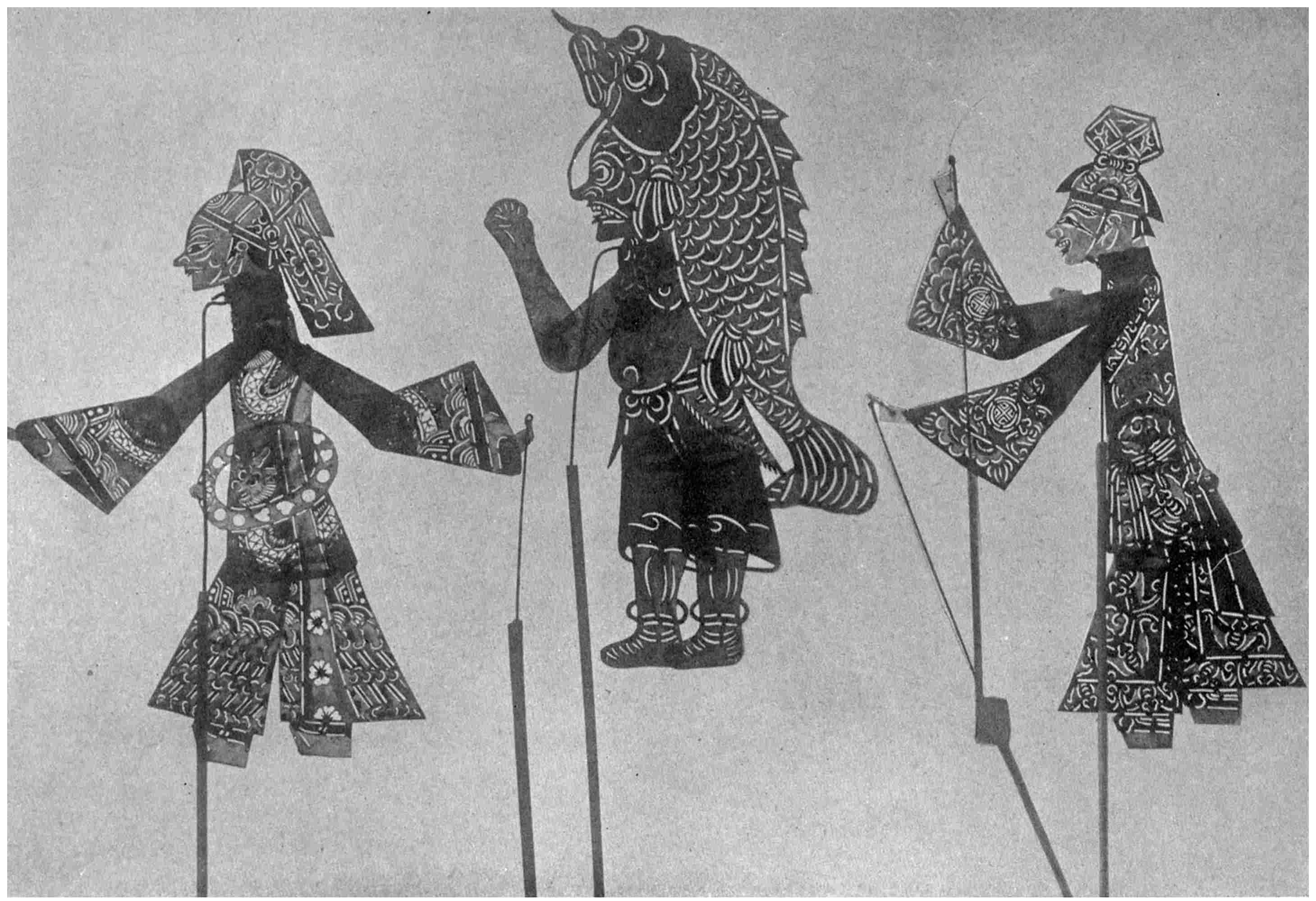

CHINESE PUPPETS

Upper: Operated from above with strings

Lower: Operated from below with sticks

[American Museum of Natural History, New York]

From an account of F. von Luschan we may imagine the usual Karagheuz performance to take place in somewhat the following manner. In any coffee house the rear corner is screened off with a thick curtain into which is inserted a frame. Over the frame a linen is stretched taut. Behind it is set a platform or table upon or at which the operator places himself and his figures. There is little equipment. Four oil lamps with several wicks are furnished with good olive oil to distribute an even illumination behind the screen. The manipulator brings on his characters and talks for them. If two of them gesticulate simultaneously, he overcomes the difficulty by holding one of the rods lightly pressed against his body, thus freeing a hand for the emergency. He must also keep time to the dancing with his castanets, stamp the floor for marching, smack himself loudly to imitate the sound of buffets and keep an eye on the lamps which threaten constantly to set fire to himself and his paraphernalia.

WAYANG FIGURES FROM THE ISLAND OF BALI

[Collected by and belonging to Mr. Maurice Sterne, New York]

These Karagheuz shows are popular not only throughout Turkey but, more or less altered, in Syria, Palestine, Arabia, Egypt, Tunis, Tripoli, and Morocco. It is recorded that in 1557 in Cairo a puppet play was instrumental in stirring up a revolt and had to be prohibited. In Arabia the shadows are decidedly debased in character, crude, and wholly inartistic. In Tunis the performances are said to be mere conglomerations of obscene incidents. Guy de Maupassant writes in his Vie Errante: “We must not forget that it was only a very few years ago that the performances of Caragoussa, a kind of obscene Punch and Judy, were forbidden. Children looked on with their large black eyes, some ignorant, others corrupt, laughing and applauding the improbable and vile exploits which are impossible to narrate.” In 1842, however, a traveller in Algiers witnessed a shadow play presenting incidents from the Arabian Nights’ Tales, in which Karagheuz was a less rude buffoon than usual. At the end of the play there appeared upon the screen the illumined inscription: “There is no God but Allah and Mohammed is his Prophet.”

* * * * *

In China the art of the shadow play has long, long ago attained a degree of perfection as high if not surpassing that of any other country. The Chinese have quaintly designed marionettes, but in the magical beauty of their shadows they are without peers. It is only within the last few decades, in fact, that the artists of Paris with the shadow plays at the Chat Noir have succeeded in at all approaching their skill and inspiration.

CHINESE SHADOW-PLAY FIGURES: COLLECTED BY B. LAUFER IN PEKIN, 1901

[American Museum of Natural History, New York]

According to legend one might infer, although scholars deem it doubtful, that the origin of puppets in the wide dominions of bygone Emperors, Celestial Ones, dates back to the earliest periods of a remarkably ancient culture. One story relates that a thousand years B.C. shadows had grown so popular and famous that King Muh commanded a famous showman named Yen Sze to come into his palace and amuse him, his wives and concubines. Yen Sze, thus honored, bestirred himself to operate the figures in an animated manner and proceeded to make his little puppets cast admiring glances at the ladies of the Court. The King became jealously enraged and ordered Yen’s head chopped off. Poor Yen Sze,—he barely escaped his horrible fate by tearing up his little figures and proving them harmless creatures of leather, glue and varnish. Another fable tells us that in the year 262 B.C. an Emperor of the Han dynasty was being besieged in the City of Ping in the Province of Schensi by the warrior-wife of Mao-Tun, named O. Now the Emperor’s adviser, being full of cunning, and having heard of the jealous disposition of the warlike lady O, devised a scheme for ingeniously ridding the Emperor of his enemies. He placed upon the walls of the beleaguered city a gorgeously dressed female puppet and by means of hidden strings made her dance alluringly upon the ramparts. Lady O, deceived by the lifelike imitation and fearing, should the city fall, that her husband, Mao-Tun, might fall in love with this seductive dancer, raised the siege and withdrew her armies from the Emperor’s City of Ping in the Province of Schensi. So wonderful, so helpful were the puppets of China in 262 B.C.!

In more modern days there are several sorts of Chinese marionettes. In any open place one might come upon the simple, peripatetic showman with a gathering of little bald-headed children around him, (hence, they say, the name Kwo or Mr. Kwo, which means Baldhead). Stepping upon a small platform the puppeteer dons a sort of sheath of blue cotton, like a big bag, tight at the ankles and full higher up. He then places his box on his shoulders with its open stage to the audience. His head is enclosed behind this stage and his hands are thrust into the dresses of the dolls and manipulate them, a finger for each arm, and for the head. The dialogue is rough, realistic humor. When the act is over he places the puppets and sheath in his box and strolls on with the complete outfit under his arm.

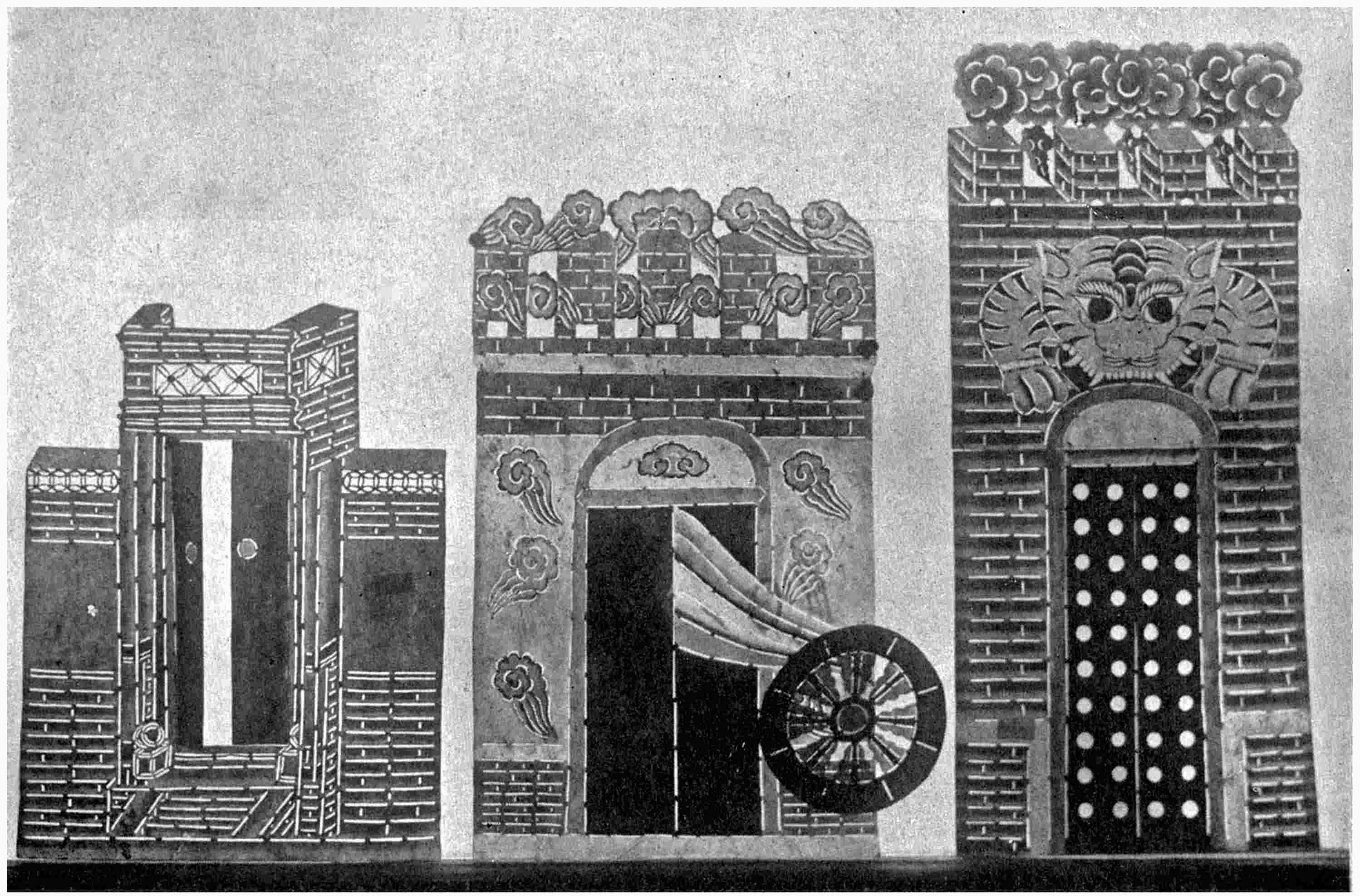

In the large stationary marionette theatres a very different state of affairs exists. Here with expensive and elaborate scenery the puppets are capable of presenting highly spectacular faeries in the manner of the later Italian and French fantoccini. The plot is generally the old one of an enchanted princess guarded by a dragon and rescued by a prince; their marriage ceremony furnishes the occasion for the spectacular display. Some dramas of a romantic or historic nature were composed especially for performances at the court of the Emperor. Sir Lytton Putney, first British Ambassador to China, has described the reception accorded him upon his arrival, one event of which was a marionette play. The chief personage in this piece was a little comedian whose antics delighted the court. The marionettes belonged to the Emperor himself, and the very clever manager of the show was a high official in the palace.

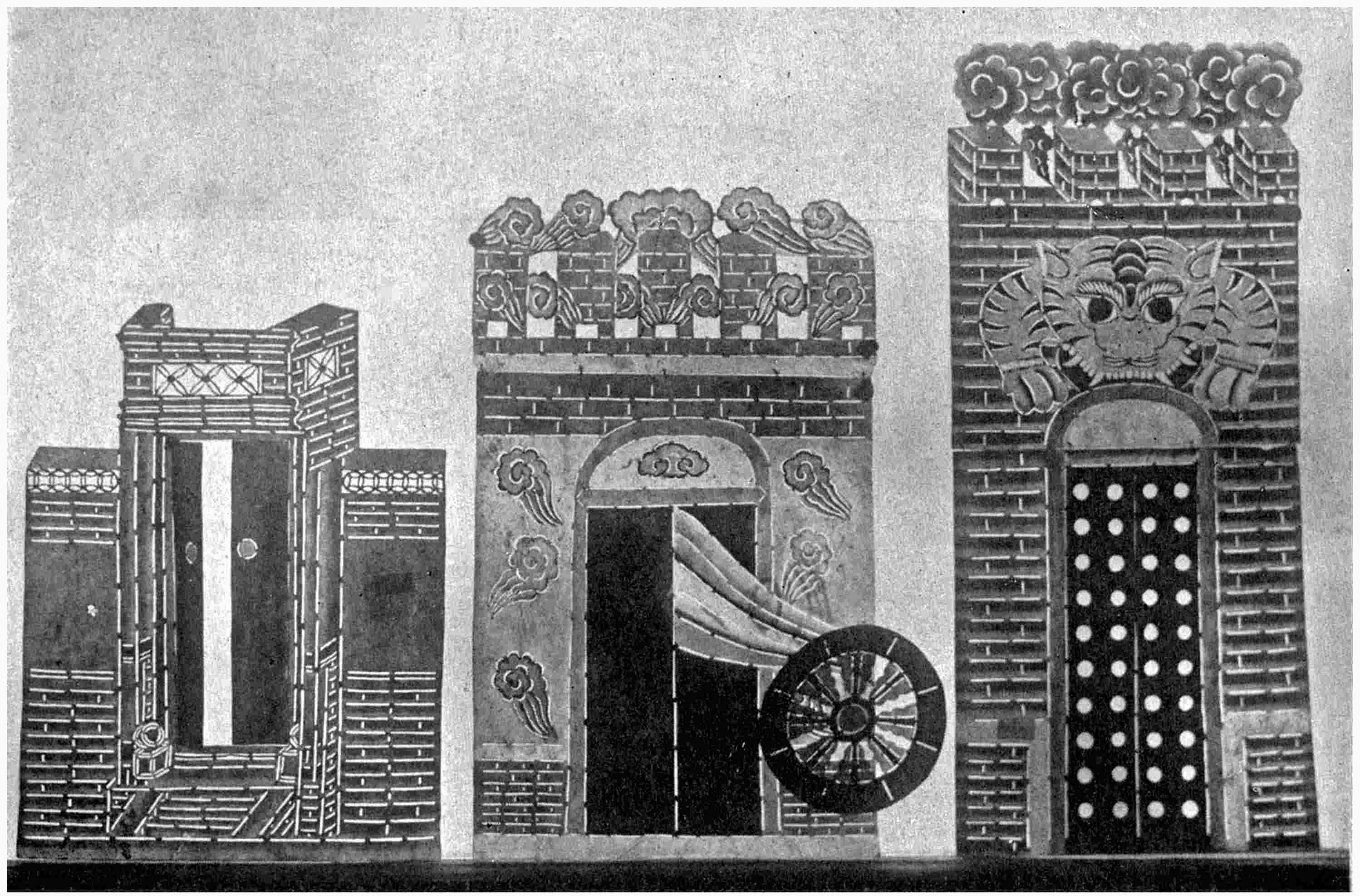

CHINESE SHADOW-PLAY FIGURES: COLLECTED BY B. LAUFER IN PEKIN, 1901

Entrance to a house; water-wheel and gate to the lower wheel; gate leading to one of the Purgatories

[American Museum of Natural History, New York]

It is the Chinese shadows, however, which are most famous and most amazing for their range of subject and variety of appeal. The figures are of translucent hide, stained with great delicacy. The colors glow like jewels when th