CHAPTER II.

JULES JACQUEMART.

THERE died, in September, 1880, at his mother’s house in the high road between the Arc de Triomphe and the Bois, a unique artist whose death was for the most part unobserved by the frequenters of picture galleries. He had contributed but little to picture galleries. There had not been given to Jules Jacquemart the pleasure of a very wide notoriety, but in many ways he was happy, in many fortunate. He was fortunate, to begin with, in his birth; for though he was born in the bourgeoisie, it was in the cultivated bourgeoisie, and it was in the bourgeoisie of France. His father, Albert Jacquemart, the known historian of pottery and porcelain, and of ancient and fine furniture, was of course a faithful and diligent lover of beautiful things, so that Jules Jacquemart was reared in a house where little was ugly and much was precious; a house organized, albeit unconsciously, on William Morris’s admirable plan, “Have nothing in your home that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.” Thus his own natural sensitiveness, which he had inherited, was highly cultivated from the first. From the first he breathed the liberal and refining air of Art. He was happy in the fact that adequate fortune gave him the liberty, in health, of choosing his work, and in sickness, of taking his rest. With comparatively rare exceptions, he did precisely the things which he was fitted to do, and did them perfectly, and being ill when he had done them, he betook himself to the exquisite South, where colour is, and light—the things we long for the most when we are most tired in cities—and so there came to him towards the end a surprise of pleasure in so beautiful a world. He was happy in being surrounded all his life long by passionate affection in the narrow circle of his home. His mother survives him—the experience of bereavement being hers, when it would naturally have been his. For himself, he was happier than she, for he had never suffered any quite irreparable loss. And in one other way he was probably happy—in that he died in middle age, his work being entirely done. The years of deterioration and of decay, in which first the artist does but dully reproduce the spontaneous work of his youth, and then is sterile altogether—the years in which he is no longer the fashion at all, but only the landmark or the finger-post of a fashion that is past—the years when a name once familiar is uttered at rare intervals and in tones of apology as the name of one whose performance has never quite equalled the promise he had aforetime given—these years never came to Jules Jacquemart. He was spared these years.

But few people care, or are likely to care very much, for the things which chiefly interested him, and which he reproduced in his art; and even the care for these things, where it does exist, does, unfortunately, by no means imply the power to appreciate the art by which they are retained and diffused. “Still-life,” using the expression in its broadest sense—the pourtrayal of objects, natural or artificial, for the objects’ sake, and not as background or accessory—has never been rated very highly or very widely loved. Here and there a professed connoisseur has had pleasure from some piece of exquisite workmanship; a rich man has looked with idly caressing eye upon the skilful record of his gold plate or of the grapes of his forcing-house. There has been praise for the adroit Dutchmen, and for Lance and Blaise Desgoffe. But the public generally—save perhaps in the case of William Hunt, his birds’ nests and his primroses—has been indifferent to these things, and often the public has been right in its indifference, for often these things are done in a poor spirit, a spirit of servile imitation or servile flattery, with which Art has nothing to do. But there are exceptions, and there is a better way of looking at these things. William Hunt was often one of these exceptions; Chardin was always—save in a rare instance or so of dull pomposity of rendering—Jules Jacquemart, take him for all in all, was of these exceptions the most brilliant and the most peculiar. He, in his best art of etching, and his fellows and forerunners in the art of painting, have done something to endow the beholders of their work with a new sense, with the capacity for new experiences of enjoyment—they have pourtrayed not so much matter as the very soul of matter. They have put matter in its finest light: it has got new dignity. Chardin did this with his peaches, his pears, his big coarse bottles, his copper saucepans, his silk-lined caskets. Jules Jacquemart did it—we shall see in more of detail presently—very specially with the finer work of artistic men in household matter and ornament; with his blue and white porcelain, with his polished steel of chased armour and sword-blade, with his Renaissance mirrors, with his precious vessels of crystal and jade and jasper. But when he was most fully himself, his work most characteristic and individual, he shut himself off from popularity. Even untrained observers could accept the agile engraver as an interpreter of other men’s pictures—of Meissonier’s inventions, or Van der Meer’s, or Greuze’s—but they could not accept him as the interpreter at first hand of the treasures which were so peculiarly his own that he may almost be said to have discovered them and their beauty. They were not alive to the wonders that have been done in the world by the hands of artistic men. How could they be alive to the wonders of this their reproduction—their translation, rather, and a very free and personal one—into the subtle lines, the graduated darks, the soft or sparkling lights, of the artist in etching?

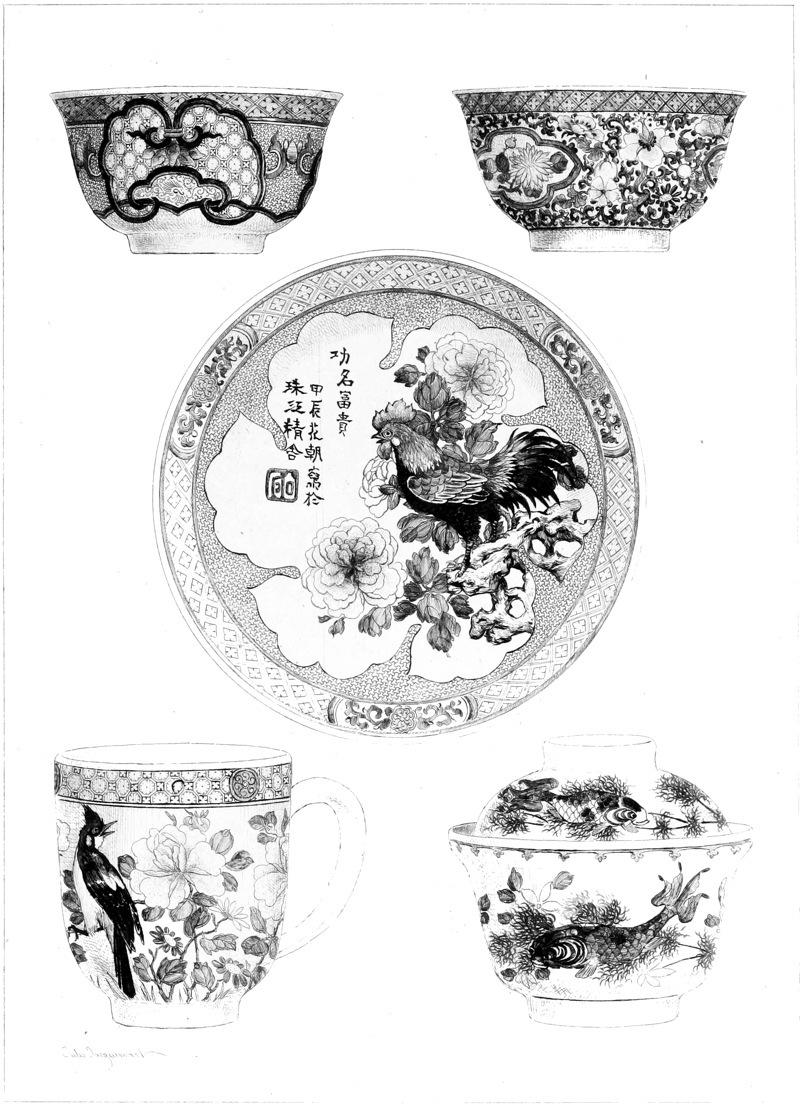

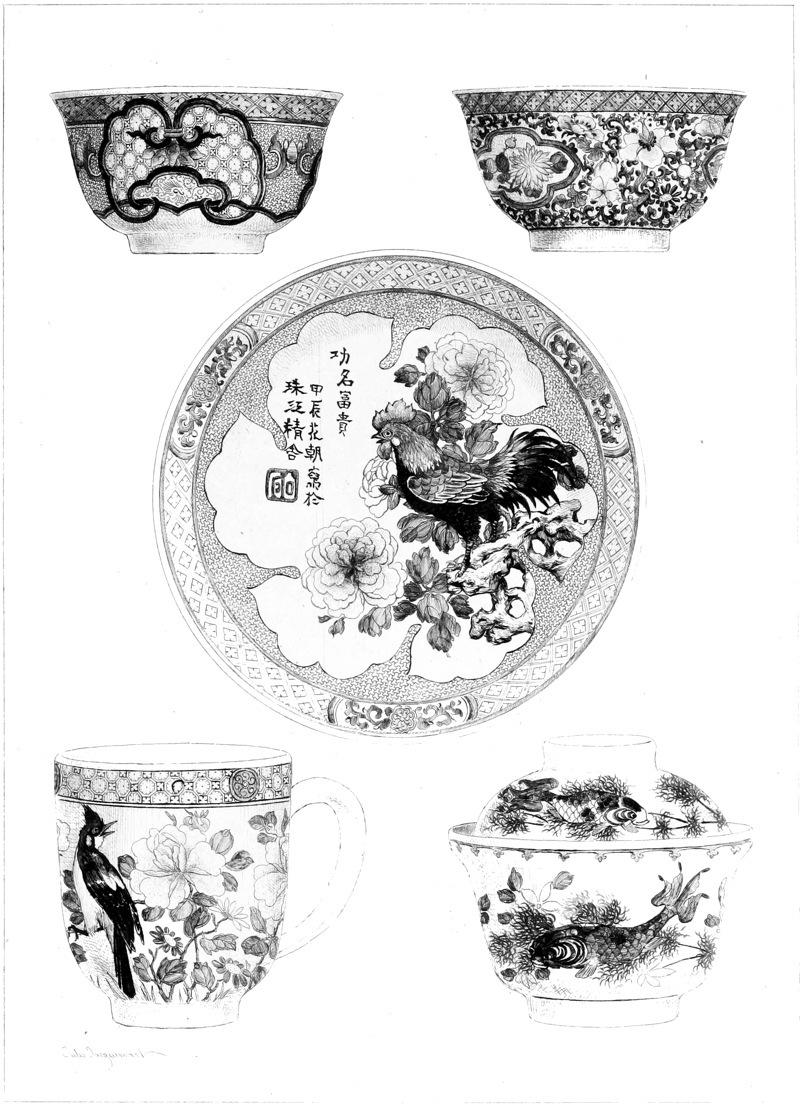

On September 7th, 1837, Jacquemart was born, in Paris, and the profession of Art, in one or other of its branches, came naturally to a man of his race. A short period of practice in draughtsmanship, and only a small experience of the particular business of etching, sufficed to make him a master. As time proceeded, he of course developed; he found new methods—ways not previously known to him. But little of what is obviously tentative and immature is to be noticed even in his earliest work. He springs into his art an artist fully armed, like Rembrandt with the wonderful portrait of his mother “lightly etched.” In 1860, when he is but twenty-three, he is at work upon the illustrations to his father’s Histoire de la Porcelaine, and though in that publication the absolute realisation of wonderful matter is not, perhaps, so noteworthy as in the Gemmes et Joyaux de la Couronne—the touch is not so large, so energetic, and so free—there is evident already the hand of the delicate artist and the eye that can appreciate and render almost unconsidered beauties. Exquisite matter and the forms that Art has given to common things have found their new interpreter. The Histoire de la Porcelaine contains twenty-six plates, most of which are devoted to Oriental china, of which the elder Jacquemart possessed a magnificent collection at a time when the popular rage for “blue and white” was still unpronounced. Many of Albert Jacquemart’s pieces figure in the book; they were pieces the son had lived with and which he knew familiarly. Their charm, their delicacy, he perfectly represented, and of each individual piece he appreciated the characteristics, passing too, without sense of difficulty, from the bizarre ornamentation of the East to the ordered forms and satisfying symmetry which the high taste of the Renaissance gave to its products. Thus, in the Histoire de la Porcelaine, amongst the quaintly naturalistic decorations from China, and amongst the ornaments of Sèvres, with their pretty boudoir graces and airs of light luxury fit for the Marquise of Louis Quinze and the sleek young abbé, her pet and her counsellor, we find, rendered with just as thorough an appreciation, a Brocca Italienne, the Brocca of the Medicis, of the sixteenth century, slight and tall, where the lightest of Renaissance forms, the thin and reed-like lines of the arabesque—no mass or splash of colour—is patterned with measured exactitude, with rhythmic completeness, over the smoothish surface. It is wonderful how little work there is in the etching, and how much is suggested. The actual touches are almost as few as those which Jacquemart employed afterwards in some of his light effects of rock-crystal, the material which he has interpreted perhaps best of all. One counts the touches, and one sees how soon and how strangely he has got the power of suggesting all that he does not actually give, of suggesting all that is in the object by the little that is in the etching. On such work may be bestowed, amongst much other praise, that particular praise which, to fashionable French criticism, delighted especially with the feats of adroitness, and occupied with the evidence of the artist’s dexterity, seems the highest—Il n’y a rien, et il y a tout.

Execution so brilliant can hardly also be faultless, and without mentioning many instances among his earlier work, where the defect is chiefly noticeable, it may be said that the roundness of round objects is more than once missing in his etchings. Strange that the very quality first taught to, and first acquired by, the most ordinary pupil of a Government School of Art should have been wanting to an artist often as adroit in his methods as he was individual in his vision! The Vase de Vieux Vincennes, from the collection of M. Léopold Double, is a case to the point. It has the variety of tone, the seeming fragility of texture and ornament, the infinity of decoration, the rendering of the subtle curvature of a flower, and of the transparency of the wing of a passing insect. It has everything but the roundness—everything but the quality that is the easiest and the most common. But so curious a deficiency, occasionally displayed, could not weigh against the amazing evidence of various cleverness, and Jacquemart was shortly engaged by the publishers and engaged by the French Government.

The difference in the commissions accorded by those two—the intelligent service which the one was able to render to the nation in the act of setting the artist about his appropriate work, and, broadly speaking, the hindrance which the other opposed to his individual development—could nowhere go unnoticed, and least of all could go unnoticed in a land like ours, too full of a dull pride in laissez faire, in private enterprise, in Government inaction. To the initiative of the Imperial Government, as Mr. Hamerton well pointed out when he was appreciating Jacquemart as long as twelve years ago, was due the undertaking by the artist of the colossal task, by the fulfilment of which he secured his fame. Moreover, if the Imperial Government had not been there to do this thing, this thing would never have been done, and some of the noblest and most intricate objects of Art in the possession of the State would have gone unrecorded—their beauty unknown and undiffused. Even as it is, though the task definitely commissioned was brought to its proper end, a desirable sequel that had been planned remained untouched. The hand that recorded the ordered grace of Renaissance ornament would have shown as well as any the intentions of more modern craftsmen—the decoration of the Eighteenth Century in France, with its light and luxurious elegance.

The Histoire de la Porcelaine, then—begun in 1860, and published in 1862 by Techener, a steady friend of Jacquemart—was followed in 1864 by the Gemmes et Joyaux de la Couronne. The Chalcographie of the Louvre—the department which concerns itself with the issue of commissioned prints—undertook the publication of the Gemmes et Joyaux. In the series there were sixty subjects, or at least sixty plates, for sometimes Jacquemart, seated by his window in the Louvre (which is reflected over and over again at every angle in the lustre of the objects he designed), would etch in one plate the portraits of two treasures, glad to give “value” to the virtues of the one by juxtaposition with the virtues of the other; to oppose, say, the brilliant transparency of the rock-crystal ball to the texture, sombre and velvety, of the vase of ancient sardonyx. Of all these plates M. Louis Gonse has given an account, sufficiently detailed for most people’s purposes, in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts for 1876. The catalogue of Jacquemart’s etchings there contained was a work of industry and of very genuine interest on M. Gonse’s part, and its necessary extent, due to the artist’s own prodigious diligence in work, sufficiently excuses, for the time at least, an occasional incompleteness of description, making absolute identification sometimes a difficult matter. The critical appreciation was warm and intelligent, and the student of Jacquemart must always be indebted to Gonse. But for the quite adequate description of work like Jacquemart’s, there was needed not only the French tongue—the tongue of criticism—but a Gautier to use it. Only a critic whose intelligence gave form and definiteness to the impressions of senses preternaturally acute, could have given quite adequate expression to Jacquemart’s dealings with beautiful matter—to his easy revelry of colour and light over lines and contours of selected beauty. Everything that Jacquemart could do in the rendering of beautiful matter, and of its artistic and appropriate ornament, is represented in one or other of the varied subjects of the Gemmes et Joyaux, save only his work with delicate china. And the work represents his strength, and hardly ever betrays his weakness. He was never a thoroughly trained academical draughtsman. A large and detailed treatment of the nude figure—any further treatment of it than that required for the beautiful suggestion of it as it occurs on Renaissance mirror-frames or in Renaissance porcelains—might have found him deficient. He had a wonderful feeling for the unbroken flow of its line, for its suppleness, for the figure’s harmonious movement. Perhaps he was not the master of its most intricate anatomy; but, on the scale on which he had to treat it, his suggestion was faultless. By the brief shorthand of his art in this matter, we are brought back to the old formula of praise. Here, indeed, if anywhere—Il n’y a rien, et il y a tout.

And as nothing in his etchings is more adroit than his treatment of the figure, so nothing is more delightful, and, as it were, unexpected. He feels the intricate unity of its curve and flow, how it gives value by its happy accidents of line to the fixed and invariable ornament of Renaissance decoration—an ornament as orderly as well-observed verse, with its settled form, its repetition, its refrain. I will mention two or three instances which seem the most notable. One of them occurs in the drawing of a Renaissance mirror—Miroir Français du Seizième Siècle—elaborately carved, but its chief grace, after all, is in its fine proportions; not so much in the perfection of the ornament as in the perfect disposition of it. The absolutely satisfactory filling of a given space with the enrichments of design, the occupation of the space without the crowding of it—for that is what is meant by the perfect disposition of ornament—has always been the problem for the decorative artist. Recent fashion has insisted, quite sufficiently, that it has been best solved by the Japanese; and they indeed have solved it, and sometimes with a singular economy of means, suggesting rather than achieving the occupation of the space they have worked upon. But the best Renaissance design has solved the problem quite as well, in fashions less arbitrary, with rhythm more pronounced, and yet more subtle, with a precision more exquisite, with a complete comprehension of the value of quietude, of the importance of rest. If it requires “an Athenian tribunal” to understand Ingres and Flaxman, it needs, at all events, some education in beautiful line to understand the art of Renaissance ornament. Such art Jacquemart of course understood absolutely, and against its ordered lines the free play of the nude figure is indicated with touches dainty, faultless, and few. Thus it is, I say, in the Miroir Français du Seizième Siècle. And to the attraction of the figure has been added almost the attraction of landscape and landscape atmosphere in the plate No. 27 of the Gemmes et Joyaux, representing scenes from Ovid, as an artist of the Renaissance had pourtrayed them on the delicate liquid surface of cristal de roche. And, not confining our examination wholly to the Gemmes et Joyaux—of which obviously the mirror just spoken of cannot form a part—we observe there or elsewhere in Jacquemart’s work how his treatment of the figure takes constant note of the material in which the first artist, his original, was working. Is it raised porcelain, for instance, or soft ivory, or smooth cold bronze, with its less close and subtle following of the figure’s curves, its certain measure of angularity in limb and trunk, its many facets, with somewhat marked transition from one to the other (instead of the unbroken harmony of the real figure), its occasional flatnesses? If it is this, this is what Jacquemart gives us in his etchings—not the figure only, but the figure as it comes to us through the medium of bronze. See, for instance, the Vénus Marine, lying half extended, with slender legs, long a possession of M. Thiers, I believe. You cannot insist too much on Jacquemart’s mastery over his material—cloisonné, with its many low tones, its delicate patterning outlined by metal ribs; the coarseness of rough wood, as in the Salière de Troyes; the sharp clear sword-blade, as the sword of François Premier, the signet’s flatness and delicate smoothness—C’est le sinet du Roy Sant Louis—and the red porphyry, flaked, as it were, and speckled, of an ancient vase, and the clear soft unctuous green of jade.

And as the material is marvellously varied, so are its combinations curious and wayward. I saw, one autumn, at Lyons, the sombre little church of Ainay, a Christian edifice built of no Gothic stones, but placed, already ages ago, on the site of a Roman temple—the temple used, its dark columns cut across, its black stones rearranged, and so the church completed—Antiquity pressed into the service of the Middle Age. Jacquemart, dealing with the precious objects he had to pourtray, came often upon such strange meetings: an antique vase of sardonyx, say, infinitely precious, mounted and altered in the twelfth century for the service of the Mass, and so, beset with gold and jewels, offered by its possessor to the Abbey of Saint Denis.

It was not a literal imitation, it must be said again, that Jacquemart made of these things. These things sat to him for their portraits; he posed them; he composed them aright. Placed by him in their best lights, they revealed their finest qualities. He loved an effective contrast of them, a comely juxtaposition; a legitimate accessory he could not neglect—that window, by which he sat as he worked, flashed its light upon a surface that caught its reflection; in so many different ways the simple expedient helps the task, gives the object roundness, betrays its lustre. Some people bore hardly on him for the colour, warmth, and life he introduced into his etchings. They wanted a colder, a more impersonal, a more precise record. Jacquemart never sacrificed precision when precision was of the essence of the business, but he did not care for it for its own sake. And the thing that his first critics blamed him for doing—the composition of his subject, the rejection of this, the choice of that, the bestowal of fire and life upon matter dead to the common eye—is a thing which artists in all Arts have always done, and will always continue to do, and for this most simple reason, that the doing of it is Art.

Not very long after the Gemmes et Joyaux was issued, as we now have it, the life of Frenchmen was upset by the war. Schemes of work waited or were abandoned; at last men began, as a distinguished Frenchman at that time wrote to me, “to rebuild their existence out of the ruins of the past.” In 1873, Jacquemart, for his part, was at work again on his own best work of etching. The Histoire de la Céramique, a companion to the Histoire de la Porcelaine, was published in that year. To an earlier period (to 1868) belong the two exquisite plates of the light porcelain of Valenciennes, executed for Dr. Le Jeal’s monograph on the history of that fabric. And to 1866 belongs an etching already familiarly known to the readers of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts and to possessors of the first edition of Etching and Etchers—the Tripod—a priceless thing of jasper, set in golden carvings by Gouthière, and now lodged among the best treasures of the great house in Manchester Square.

But it is useless to continue further the chronicle of the triumphs that Jacquemart won in the translation, in his own free fashion of black and white, of all sorts of beautiful matter. Moreover, in 1873, the year of the issue of his last important series of plates, Jules Jacquemart, stationed at Vienna, as one of the jury of the International Exhibition there, caught a serious illness, a fever of the typhoid kind, and this left him a delicacy which he could never overcome; and thenceforth his work was limited. Where it was not a weariness, it had to be little but a recreation, a comparative pause. That was the origin of his performances in water colour, undertaken in the South, whither he repaired at each approach of winter. There remains, then, only to speak of these drawings and of such of his etched work as consisted in the popularisation of painted pictures. As a copyist of famous canvasses he found remunerative and sometimes fame-producing labour.

As an interpreter of other men’s pictures, it fell to the lot of Jacquemart, as it generally falls to the lot of professional engravers, to engrave the most different masters. But with so very personal an artist as he, the interpretation of so many men, and in so many years, from 1860, or thereabouts, onwards, could not possibly be always of equal value. Once or twice he was very strong in the reproduction of the Dutch portrait painters; but as far as Dutch painting is concerned, he is strongest of all when he interprets, as in one now celebrated etching, Jan van der Meer of Delft. Der Soldat und das lachende Mädchen was one of the most noteworthy pieces in the rich cabinet of M. Léopold Double. The big and somewhat blustering trooper common in Dutch Art, sits here engaging the attention of that pointed-faced, subtle, but vivacious maiden peculiar to Van der Meer. Behind the two, who are occupied in contented gazing and contented talk, is the bare sunlit wall, spread only with its map or chart—the Dutchman made his wall as instructive as Joseph Surface made his screen—and by the side of the couple, throwing its brilliant, yet modulated light on the woman’s face and on the background, is the intricately patterned window, the airy lattice. Rarely was a master’s subject or a master’s method better interpreted than in this print. Frans Hals once or twice is just as characteristically rendered. But with these exceptions it is Jacquemart’s own fellow-countrymen whom he renders the best. Seldom was finish so free from pettiness or the evidence of effort as it is in the Défilé des populations lorraines devant l’Impératrice à Nancy. Le Liseur is even finer—Meissonier again; this time a solitary figure, with bright, soft light from window at the side, as in the Van der Meer of Delft. The suppleness of Jacquemart’s talent—the happy speed of it, rather than its patient elaboration—is shown by his renderings of Greuze, the Rêve d’amour, a single head, and L’Orage, a sketchy picture of a young and frightened mother kneeling by her child exposed to the storm. Greuze, with his cajoling art—which, if one likes, one must like without respecting—is entirely there. So, too, Fragonard, the whole ardent and voluptuous soul of him, in Le Premier Baiser. Labour it is possible to give in much greater abundance; but intelligence in interpretation cannot go any further or do anything more.

Between the etchings of Jacquemart and his water-colour drawings there is little affinity. The subjects of the one hardly ever recall the subjects of the other. The etchings and the water colours have but one thing in common—an extraordinary lightness of hand. Once, however, the theme is the same. Jacquemart etched some compositions of flowers; M. Gonse has praised them very highly: to me, elegant as they are, fragile of substance and dainty of arrangement, they seem inferior to that last-century flower-piece which we English are fortunate enough to know through the exquisite mezzotint of Earlom. But in the occasional water-colour painting of flowers—especially in the decorative disposition of them over a surface for ornament—Jacquemart is not easily surpassed; the lightness and suggestiveness of the work are almost equal to Fantin’s. A painted fan by Jacquemart, which is retained by M. Petit, the dealer, is dexterous, yet simple in the highest degree. The theme is a bough of the apple-tree, where the blossom is pink, white, whiter, then whitest against the air at the branch’s end.

But generally his water colour is of landscape, and a record of the South. Perhaps it is the sunlit and flower-bearing coast, his own refuge in winter weather. Perhaps, as in a drawing of M. May’s, it is the mountains behind Mentone—their conformation, colours, and tones, and their thin wreaths of mist—a drawing which M. May, himself an habitual mountaineer in those regions, assures me is of the most absolute truth. Or, perhaps, as in another drawing in the same collection, it is a view of Marseilles; sketchy at first sight, yet with nothing unachieved that might have helped the effect; not the Marseilles, sunny and brilliant, parched and southern, of most men’s observation—the Marseilles even of the great observer, the Marseilles of Little Dorrit—but the busy port, with its ever-shifting life, under an effect less known; the Marseilles of an overcast morning: all its houses, its shipping and its quays, grey or green and steel-coloured. Such a work is a masterpiece, with the great quality of a masterpiece, that you cannot quickly exhaust the restrained wealth of its learned simplicity. To speak about it one technical word, we may say that while it belongs by its frank sketchiness to the earlier order of water-colour art, an art of rapid effect, as practised best by Dewint and David Cox, it belongs to the later order—to contemporary art—by its unhesitating employment of body colour.

The true source of the diversity of Jacquemart’s efforts, which I have now made apparent, is perhaps to be found in a vivacity of intellect, a continual alertness to receive all passing impressions. That alone makes a variety of interests easy and even necessary. That pushes men to express themselves in art of every kind, and to be collectors as well as artists, to possess as well as to create. Jacquemart inherited the passion of a collector; it was a queer thing that he set himself to collect. He was a collector of shoe-leather; foot-gear of every sort and of every time. His father, Albert Jacquemart, had held that to know the pottery of a nation was to know its history. Jules saw many histories, of life and travel, and the aims of travel, in the curious objects of his collection. Their ugliness—what would be to most of us the extreme distastefulness of them—did not repel him. Nor were his attentions devoted chiefly to the dainty slippers of a dancer—souvenirs, at all events, of the art of the ballet, very saleable at fancy fairs of the theatrical profession. He etched his own boots, tumbled out of the worst cupboard in the house. He looked at them with affection—souvenirs de voyage. The harmless eccentricity brings down, for a moment, to very ordinary levels, this watchful and exquisite artist, so devoted generally to high beauty, so keen to see it.

What more would he have done had the forty-three years been greatly prolonged, a spell of life for further work accorded, Hezekiah-like, to a busy labourer upon whom Death had laid its first warning hand? We cannot answer the question, but it must have been much, so variously active was his talent, so fertile his resource. As it is, what may he hope to live by, now that the most invariably fatal of all forms of consumption, the most fatal while the least suspected, la phthisie laryngée, has arrested his effort? A very gifted, a singularly agile and supple translator of painters’ work, he may surely be allowed to be, and a water-colour artist, perfectly individual, yet hardly actually great; his strange dexterity of hand at the service of fact, not at the service of imagination. He recorded nature; he did not exalt or interpret it. But he interpreted Art. He was alive, more than any one has been alive before, to all the wonders that have been wrought in the world by the hands of artistic men.