CHAPTER III.

J. A. M. WHISTLER

YEARS ago James Whistler was a person of high promise: he has since been an artist often of agreeable and exquisite, though sometimes of incomplete and apparently wayward, performance. He has the misfortune to have been greatly known to a large public as the painter of his least desirable works, these having reached an easy notoriety, while the others have thus far too much escaped a general fame. Much of Mr. Whistler’s art has the interest of originality, and some of it the charm of beauty; and yet the measure of originality has at times been over-rated, through the innocent error of the budding amateur, who, in the earlier stage of his enlightenment, confuses the beginning with the end, accepts the intention for the adequate fulfilment, and exalts an adroit sketch into the rank of a permanent picture. Mr. Irving as Philip of Spain—three years ago at the Grosvenor—was a murky caricature of Velasquez; the master’s sketchiness remained, but his decisiveness was wanting. And in some of the Nocturnes the absence, not only of definition, but of gradation, would point to the conclusion that they are but engaging sketches. In them we look in vain for all the delicate differences of light and hue which the scenes depicted present. Like the landscape art of Japan, they are harmonious decorations, and a dozen or so of such engaging sketches placed in the upper panels of a lofty apartment would afford a justifiable and welcome alternative even to noble tapestries or Morris wall-papers. But, on the large scale on which they are painted—a scale in which their well-considered sketchiness is carefully emphasized—it is in vain that we endeavour to receive them as cabinet pictures. They suffer curiously when placed against work not of course of petty and mechanical finish, but of patient achievement. But they have merits of their own; nor are their merits too common. So short a way have they proceeded into the complications of colour, that they avoid the incompatible: they avoid it cleverly; they say little to the mind, but they are restful to the eye, in their agreeable simplicity and limited suggestiveness. They are the record of impressions. So far as they go, they are right; nay, in one sense they are better than right, for they are charming.

And, moreover, there is evidence enough elsewhere that Mr. Whistler, confined to colour alone, can produce more various and more intricate harmonies than those of a Nocturne in silver and blue, than those of a scherzo in blue, or than those even in that fascinating portrait of Mrs. Meux, in which it was not so much the face as the figure and the movement that came to be deftly suggested, if hardly elaborately expressed. A great apartment in the house of Mr. Leyland, which Mr. Whistler has decorated, has shown that a long and concentrated effort at the solution of the problems of colour is not beyond the scope of an artist who has rarely mastered the subtleties of the intricate human form. It has shown, moreover, that his solution of such problems can be strikingly original. As a decorative painter—as a painter of large or brilliant sketches—Mr. Whistler has had few superiors in any time or land. His skill is sometimes genius here. Why, in the Grosvenor Gallery, the very year in which the irrepressible painter proffered the most unwelcome of his Nocturnes, there was a quite delightful picture, suggested, indeed, by Japanese Art, but itself not less subtle than the art which prompted it—A Variation in Flesh-colour and Green—bare-armed damsels of the farthest East, lounging in attitudes of agreeable abandonment in some balcony or court open to the genial sunlight and to the soft air. The damsels—they were not altogether meritorious. The draughtsmanship displayed in them was anything but “searching.” But the picture had a quality of cool refreshment such as the gentle colour and clean-shining material of Luca della Robbia affords to the beholder of Tuscan Art, as he comes upon Tuscan Art under Tuscan skies.

The interest of life—the interest of humanity—has confessedly occupied Mr. Whistler but little; yet in spite of his devotion to the art qualities of the peacock, it has not been given to him to be quite indifferent to the race to which he belongs. His portraits, sometimes, whatever may be his theories, have not been very obviously considered as arrangements of colour only for colour’s sake. They may even have profited by the adoption of hues such as suited their themes, and here Mr. Whistler may have delivered, through his language of colour, a message which some men would have intrusted to line alone. Anyhow he has been able to paint with admirable expressiveness a portrait of his mother, and to have recorded on a doleful canvas the head and figure of Carlyle, and in both, the simplicity and veracity of effect are things to be noted. Not indeed that the pictures are without mannerism: the straight and stiffish disposition of the lines in the first is not so much a merit as a peculiarity. But a certain dignified quietude and a certain reticent pathos are apparent in the portrait of the lady, and the rugged simplicity of Carlyle—a simplicity which his own generation received with so naive an admiration—is suggested not only with skill of hand, but with the mental skill that discovers quickly, in presence of a subject, wherein lies the best opportunity for high success in treating it.

But I take it to be admitted by those who do not conclude that the art is necessarily great which has the misfortune to be unacceptable, that it is not by his paintings so much as by his etchings that Mr. Whistler’s name may aspire to live. In painting, his success is infrequent and it is limited—though when it occurs, its very peculiarity gives us a keen relish for it—in etching, it is neither limited nor rare, though of course it is not uninterrupted nor unbroken. In painting, Mr. Whistler is an impressionist—he is an impressionist in etching, but etching permits the record of the impression only, while painting demands at all events the occasional capacity to realise with weeks of labour what a few hours might happily enough suggest. Moreover—and the circumstance is odd and noteworthy—it is in his etchings that Mr. Whistler has reached realisation the best, and he has reached it, in the earlier Thames-side work of twenty years ago, with no sacrifice whatever of freedom and of frankness in treatment. His best painting betrays something of that exquisite sensitiveness, that almost modern sensitiveness, to pleasurable juxtapositions of delicate colour which we admire in Orchardson, in Linton, and in Albert Moore; it betrays sometimes, as in a portrait of Miss Alexander, a deftness of brushwork, in the wave of a feather, in the curve of a hat, that recalls for a moment even the great names of Velasquez and of Gainsborough; and of high art qualities it betrays not much besides—though these, which are very rare, we are properly grateful for. But the etchings—that is indeed another matter. They must be considered in detail. No criticism is wasted that concerns itself carefully with them, and that points out from the many, which are fair, and which are exquisite, and which are flagrantly offensive.

In some of his prints, Mr. Whistler makes good a claim to live by the side of the finest masters of the etching needle, and a familiarity with Rembrandt and with Méryon increases rather than lessens our interest in the American of to-day. But Mr. Whistler has etched too much for his reputation, or at least has published too much. No one who can look at work of Art fairly, demands that it shall be faultless; least of all can that be demanded of work of which the very virtue lies sometimes in its spontaneousness; but one has good reason to demand that the faults shall not outweigh the merits. Now in some of Mr. Whistler’s figure-pieces, executed with the etching-needle, and offered to the public indiscreetly, the commonness and vulgarity of the person pourtrayed find no apology in perfection of pourtrayal—the design is uncouth, the drawing is intolerable, the light and shade an affair of a moment’s impressiveness, with no subtlety of truth to hold the interest that is at first aroused. See, as one instance, the etching numbered 3 in Mr. Thomas’s published catalogue—notice the size of the hands. And see again No. 56, in which the figure is one vast black triangle, in which there is apparently not a single quality which work of Art should have. The portraits of Becquet, the violoncello player, of one Mann, and of one Davis, have character, with no mannerism, but with a good simplicity of treatment. But neither face pourtrayed, nor Art pourtraying it, is of a kind to command a prolonged enjoyment. On the other hand, in some of the etchings or dry points, not, it seems, included in the catalogue, and in the refined and sensitive little etching of Fanny Leyland there is apparent a distinct feeling for grace of contour—for the undulations of the figure and its softness of modelling. These are but the briefest sketches—they have a quality of their own. It is not ungenerous to suggest that carried further they might have failed. For the true genius of etching is in them as they are. As they are they have not failed.

Many have been the themes which, in the art of the aquafortist, Mr. Whistler has essayed. He has essayed landscape; he has drawn a tree in Kensington Gardens, and a tree in the foreground of the Isle St. Louis, Paris; but that tree at least seems of no known form of vegetable growth—it has the air of an exploding shell. Here and there—occupied with those juxtapositions of light and shade which fascinated the masters of Holland—Mr. Whistler has drawn interiors, and in one of his interiors we note a success second only to the very highest these Dutchmen attained. This is the interior described as The Kitchen. Only the finest, the most carefully printed impressions possess the full charm; but when such an impression presents itself to the eye, the Dutch masters, who have followed most keenly the glow and the gradation of light on chamber-walls, are seen to be almost rivalled. The kitchen is a long and narrow room, at the far end of which, away from the window and the keen light, stand artist and spectator. Farthest of all from them the light vine leaves are touched in with a grace that Adrian van Ostade—a master in this matter—would not have excelled. By the embrasure of the window, just before the great thickness of the wall, stands a woman, angular, uncomely, of homely build, busied with “household chares.” In front of her comes the sharp sunlight, striking the thick wall-side, and lessening as it advances into the shadow and gloom of the humble room; wavering timidly on the plates of the dresser, in creeping half gleams which reveal and yet conceal the objects they fall upon. The meaningless scratch and scrawl of the bare floor in the foreground is the only fault that at all seriously tells against the charm of work otherwise beautiful and of keen sensitiveness; and the case is one in which the merit is so much the greater that the fault may well be ignored or its presence permitted. Again, La Vieille aux Loques—a weary woman of humblest fortunes and difficult life—shows, I think, that Mr. Whistler has now and then been inspired by the pathetic masters of Dutch Art.

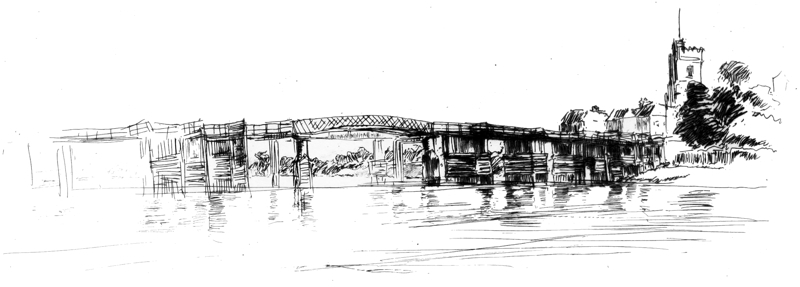

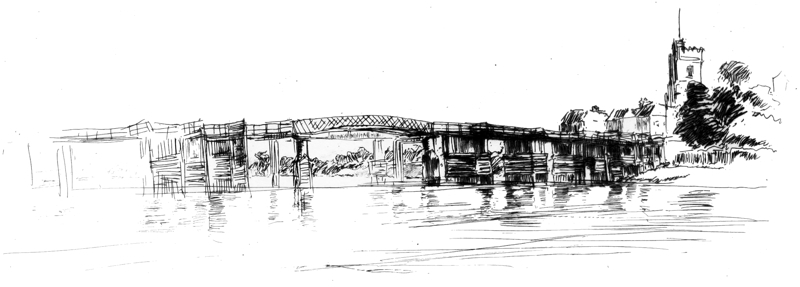

We have seen already that two things have much occupied Mr. Whistler—the arrangement of colours in their due proportions, the arrangement of light and shade. And the best results of the life-long study which, by his own account, he has given to the arrangement of colour are seen in the work that is purely, or the work that is practically, decorative—the work that escapes the responsibility of a subject. And the best results of the study of the arrangements of light and shade are seen in a dozen etchings, most of which—but not The Kitchen and not the Vieille aux Loques—belong to that series in which the artist has recorded for our curious pleasure the common features of the shores of the Thames. Here also there is evident his feeling, not exactly for beauty, but at all events for quaintness of form, for form that has character. It had occurred to no one else to draw with realistic fidelity the lines of wharf and warehouse along the banks of the river; to note down the pleasant oddities of outline presented by roof and window and crane; to catch the changes of the grey light as it passed over the front of Wapping. Mr. Whistler’s figure-drawing, generally defective and always incomplete, has prevented him from seizing every characteristic of the sailor-figures that people the port. The absence, seemingly, of any power such as the great marine painters had, of drawing the forms of water, whether in a broad and wind-swept tidal river or on the high seas, has narrowed and limited again the means by which Mr. Whistler has depicted the scenes “below Bridge.” But his treatment of these scenes is none the less original and interesting. By wise omission, he has managed often to retain the sense of the flow of water or its comparative stillness. Its gentle lapping lifts the keels of the now emptied boats of his Billingsgate. It lies lazy under the dark warehouses of his Free Trade Wharf. It frets and flickers and divides in pleasant light against the woodwork of the bridge in the larger Putney.

The limitations of Mr. Whistler’s art are very conspicuous in a more recent experiment than the original Thames-side series—the series of Venice. So evident, indeed, are they in that set that the set has been undervalued by many amateurs of taste, who have exacted too much that Mr. Whistler should give them, not what he was best able to see in Venice, but what cultivated readers of Art history have been most accustomed to see there. The Venice series is in the etcher’s later manner—a style in which ever-increasing reliance is placed on the faculty of slight and suggestive sketching. Now etching, even when practised with the greatest possible union of fidelity and freshness, is hardly the appropriate medium for conveying the charm of delicate architecture. Of such architecture Méryon himself only now and then essayed to give the charm, and he essayed it, deliberately, at the cost of abandoning not a little of the etcher’s freedom—he became, for the nonce at least, a “great original engraver;” he took his art beyond its habitual bounds. His triumph justified him. But Mr. Whistler, even in his earlier manhood, when those of the Thames etchings which are the fullest of detail were wrought with sureness and precision of hand, never betrayed either the capacity or the will to reproduce the charm of delicate architecture. Yet in an art to which colour is denied, the charm of delicate architecture must be the charm of Venice. It remained, however, for Mr. Whistler to see whether the place had yet some aspects which his etching could record—an impression, not a reproduction: that was all that could be looked for. And Mr. Whistler etched his impressions with curious uncertainty and curious inequality. He was now adroit, now wavering. He took from London to Venice his happy fashion of suggesting lapping water. He looked at Venice as a whole, keenly, delicately, but never in detail—we had bird’s-eye views of it. It had been interesting to wonder what would be the vision granted to a fantastic genius of a fantastic city. Well, little new came of it, in etching—nothing new that was beautiful. Afterwards, in a series of pastels, it became clear who it was that had seen Venice. It was Mr. Whistler the exquisite colourist, not the exquisite etcher.

Mr. Whistler’s fame as an aquafortist, then, rests chiefly still on his Thames-side work; and, even there, less on the faint agreeable sketches done of later years, though these have their charm, like the better of his painted Nocturnes, than on the work of his first maturity. The London Bridge and the Free Trade Wharf and one or two Putneys—one of them is in this book—may be named, however, among the happiest examples of the later art that is specially brief in recording an impression. The spring of the great arch in London Bridge, as seen from below, from the water-side, is rendered, it seems, with a suggestion of power in great constructive work, such as is little visible in the tender handling of so many of the prints of the river. The Free Trade Wharf is a very exquisite study of gradations of tone and of the receding line of murky buildings that follows the bend of the stream. It is, in its best printed impressions, a thing of faultless delicacy. A third river-piece, not lately done, has been rather lately retouched—the Billingsgate: Boats at a Mooring. In the retouch is an instance of the successful treatment of a second “state” or even a later “state” of the plate, and such as should be a warning to the collector who buys “first states” of everything—the Liber Studiorum included—and “first states” alone, with dull determination. Of course the true collector knows better: he knows that the impression is almost all, and the “state” next to nothing, except as indicating what is probable as to the condition of the plate, and he must gradually and painfully acquire the eye to judge of the impression.

A few years ago Mr. Whistler retouched his Billingsgate for the proprietors of the Portfolio, and the proof impressions of the state issued by them reach the highest excellence of which the plate has been capable. Not sheltering itself under the extreme simplicity and singleness of aim kept so adroitly in the Free Trade Wharf and in the London Bridge, it falls into faults which these avoid. The ghostliness of the foreground figures demands an ingenious theory for its justification, and this theory no one has advanced. But the solidity of the buildings introduced into this plate—the clock-tower and the houses upon the quay—are a rare achievement in etching. For once the houses are not drawn, but built, like the houses and the churches and the bridges of Méryon. The strength of their realisation lends delicacy to the thin-masted fishing boats with their yet thinner lines of cordage, and to the distant bridge in the grey mist of London, and to the faint clouds of the sky. Perhaps yet more delicate than the Billingsgate is the Hungerford Bridge, so small, yet, in a fine proof, so spacious and airy. It lacks substance, of course, and solidity—and so does the impression of landscape in a dream.

Finally, there are the Thames Police, the Tyzack Whiteley, and the Black Lion Wharf. These, which were executed a score of years since, are the most varied and complete studies of quaint places now disappearing—nay, many of them already disappeared—of places with no beauty that is very old or very graceful, but with interest to the every-day Londoner and interest, too, to the artist. Here are small warehouses falling to pieces, or poorly propped even when they were sketched, and vanished now to make room for a vaster and duller uniformity of storehouse front. Here are narrow dwelling-houses of our Georgian days, with here a timber facing and there a quaint bow window, many-paned—narrow houses of sea-captains, or the riverside tradesfolk, or of custom-house officials, the upper classes of the Docks and the East-end. These too have been pressed out of the way by the aggressions of great commerce, and the varied line that they presented has ceased to be. Of all these riverside features, Thames Police is an illustration interesting to-day and valuable to-morrow. And Black Lion Wharf is yet fuller of happy accident of outline and happy gradation of tone, studied amongst common things which escape the common eye.

It is a pleasure to possess such faithful and spirited records of a departing quaintness, and it is an achievement to have made them. It would be a pity to remove the grace from the achievement by insisting that, as in Nocturne and Arrangement, the art was burdened by a here unnecessary theory; that the study of the “arrangement of line and form” was all, and the interest of the association nothing. When Dickens was tracing the fortunes of Quilp on Tower Hill, and on that dreary night when the little monster fell from the wharf into the river, he did not think only of the cadence of his sentences, or his work would never have lived, or lived only with the lovers of curious patchwork of mere words. Perhaps, without his knowing it, some slight imaginative interest in the lives of Londoners prompted Mr. Whistler, or strengthened his hand, as he recorded the shabbiness that has a history, the slums of the eastern suburb, and the prosaic service of the Thames. Here, and often elsewhere, his work, if it has shown some faults to be forgiven, has shown, in excellence, qualities that fascinate. The Future will forget his failures, to which in the Present there has somehow been accorded, through the activity of friendship or the activity of enmity, a publicity rarely bestowed upon failures at all; but it will remember the success of work that is peculiar and personal. These best things we have dwelt upon are not to be denied that length of days which is the portion of exquisite Art.