CHAPTER IV.

ALPHONSE LEGROS.

ANY generation since the brilliant times of Art—since the sixteenth century in Italy, the seventeenth in Holland, the eighteenth in England and in France—has had to deem itself fortunate if it has produced three or four artists of individuality united with large attainment; and it is much to be surmised that no generation will have greater cause than our own to think it has done well if it has produced even as many. Notorieties of the moment may always be counted by the score, but fame remains so rarely for the most popular, that the serious student of the work of a master in any art has no reason to question his own judgment when it points him to admiration, merely because the object of his admiration is not to be counted among the immediate successes of the hour. Legros is not an immediate success. He has worked for five-and-twenty years, and there are intelligent people who see little in his pictures beyond their first ugliness. Each to his taste—we cannot always blame them; and Legros has been ugly sometimes gratuitously, sometimes with wantonness. But Legros is also a very grave and enduring master, whose work is now full of mistake, and now of power, and now again is certainly touched with that higher and keener faculty we call inspiration.

The etchings of Legros range already, however, over a period of seven-and-twenty years; and that he began so young, and at a time when etching was not popular and the art had not become a trade, is a proof at least of the spontaneity of his pursuit of it. By temperament and instinct he was as much etcher as painter, perhaps even more. The process of etching being—always in skilled hands, of course—perhaps the readiest for the rendering of impressions and the expression of artistic thought, it is natural that Legros, whose art, whatever it may lack in immediate attractiveness, is one undoubtedly of impressions and of thoughts, should have turned to this process. And so well, indeed, has he increased his command of it—always with reference to his own particular business, to the order of impressions it is his own task to convey—that, though there are, indeed, several of his paintings which have the qualities of a master’s work, we get the best of him in his etchings. Great is the technical progress he has made in these since some of the first plates catalogued so well by M. Poulet-Malassis and Mr. Thibaudeau, but it is not to be imagined that the progress has been uninterrupted. Incompleteness and uncertainty are still likely to be visible. His execution, skilful at one time, and entirely responsive to his desire, is at another time halting, wayward, insufficiently controlled and directed. Therefore, though, as I say, the execution is not seldom excellent—economical of means and yet rich in the possession of various means—it would rarely be in itself the occasion of attracting notice to his work. With Legros, it is the conception that dominates. The conception is often such as recalls the highest achievements of Art.

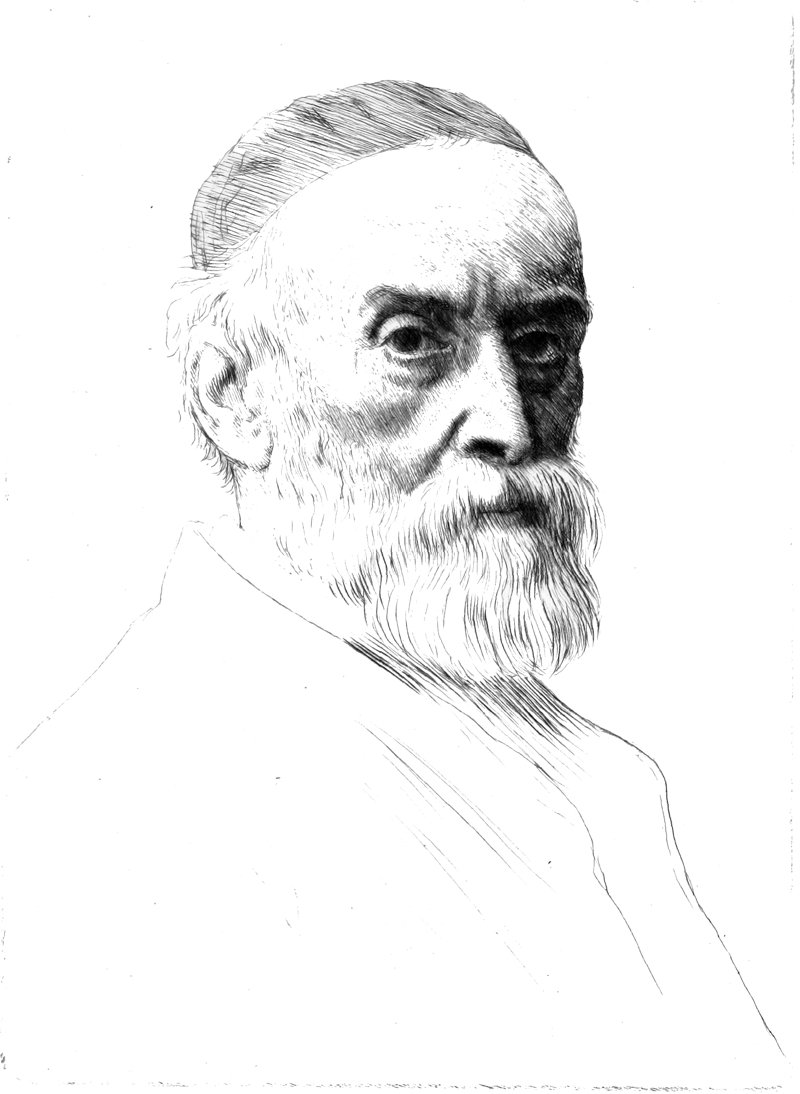

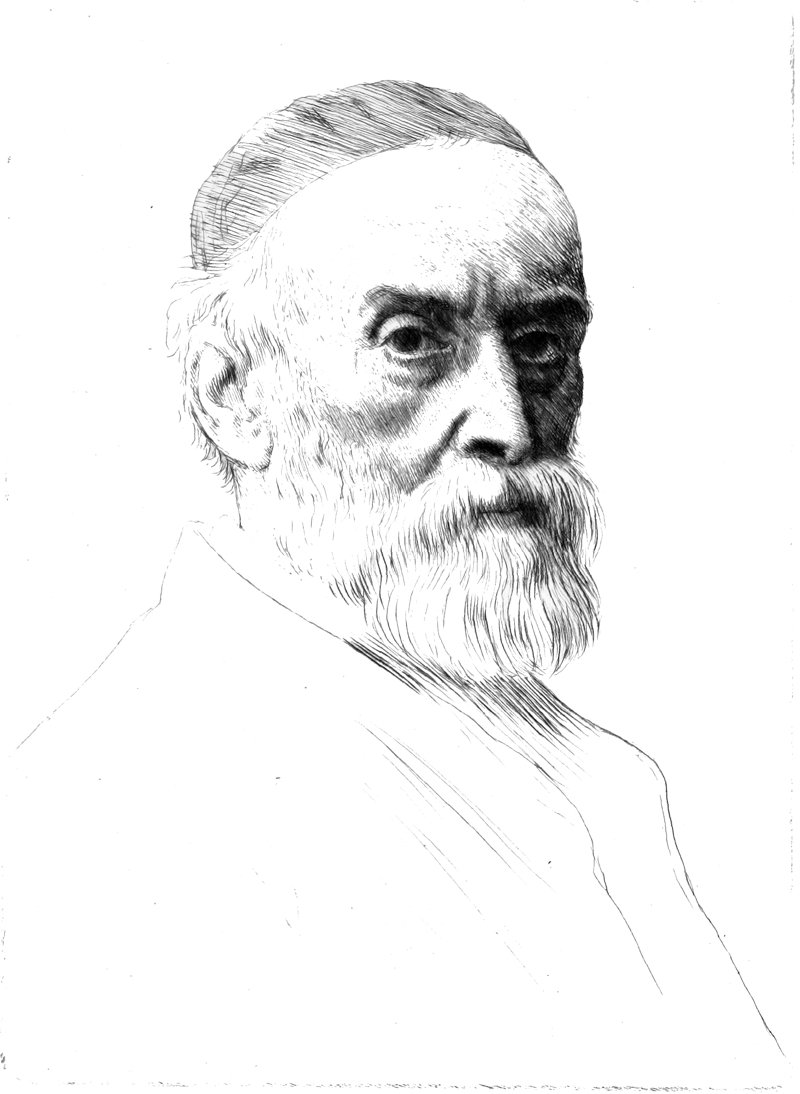

But the imagination of Legros, in virtue of which, quite as much as by occasional mannerisms of handling, he recalls that older and more pregnant Art which has well nigh passed from the very ken of the producers of our own day’s trivial array, is not in any sense derived from this or that past master; it is charged, on the contrary, in his most considerable pieces with a serious and pathetic poetry quite his own. Here and there, indeed, as in one early work—Procession dans les Caveaux de Saint-Médard—it is not imagination at all, as that is generally understood, but the keen observation of an artist content to reproduce, that alone is remarkable; and here there is a certain amount of audacity in the fidelity with which he has rendered the commonplace, the mean, the narrow faces of a certain section of the Parisian lower bourgeoisie engaged in devotions which there is no beauty of form or of thought to make interesting to the beholder. It is a piece of pure realism—the hideous flounces and more hideous crinolines, the squat figures, the slop-shop fashions, the common faces empty of records. And in this pure and unrelieved realism there is a certain value, if there is no charm. But the pieces to which Legros will owe such fame as the better-judging connoisseurs and critics shall eventually accord him are those in which the artistic instinct and desire of beauty, either of form or of thought, has found some expression. It will be in part by such masculine, yet refined and graceful, portraits as those of M. Dalou and Mr. Poynter, such subtle ones as that of Cardinal Manning, such pathetic ones as that of M. Rodin here, that Legros will stand high. It will be in part by the etchings in which the pourtrayal of actual life has been guided by the research for beauty, as, for instance, in the Chœur d’une Eglise Espagnole, where not only is the head firm and dignified and the lighting more intricate than is usual with this master, but where the composition of bent figure and curved violoncello is of great repose and refinement of beauty. A more various specimen of the same type is to be found in a fine impression of Les Chantres Espagnols. They are eight in the choir of a church—four sit in the stalls, the others stand, of whom one turns the page of a missal placed on a lectern. The scene is mostly dark—mostly even very dark—but the light, by a very skilled treatment of it, falls here and there on lectern, missal, and hand of the old man sitting in the choir. The observation of reality in this plate has been at the same time keen and poetical, for nothing can be truer and nothing more impressive than the study of old faces out of which so much of the desire of life has gone, and the study of gestures which are those of hand and will waxing feeble. Two men, at least, are placed together in a pathetic harmony of weakness: the drooping hand of one and his drooped head, as he sits in his long-accustomed place; the open mouth of the other—his mouth opened with the feebleness of a decayed intelligence, with the slow understandings of a departing mind. Or, not to insist too much on a picturesqueness in which pathos predominates, notice, when the occasion presents itself, the first rendering of the subject known as the Lutrin, with its acolyte of rare youthful dignity; or as an example of work in which some little beauty of modelling has been sought to be united even with every-day realism, see the design of the bare knee in L’Enfant Prodigue.

But where Legros is most apart and alone is, after all, in the subjects which owe most to the imagination, and of these the very finest are La Mort du Vagabond, La Mort et le Bûcheron, and Le Savant endormi. Something of the art that gives interest to these pieces is contained in the careful persistence with which the etcher brings the realism of physical ugliness into close contact and contrast with the spiritual and supernatural. A comely and well-to-do youth slumbering in his chair at the Marlborough could have no dreams an artist of Legros’s nature would think worthy of recording, but the ugly votary of science and intellectual speculation, who sleeps, from sheer weariness, in the armchair before which are still the implements of his study and research, has the dignity of strained endeavour; and M. Legros, in pourtraying him and suggesting the subjects of his dream, has reached an elevation which separates him from most of his contemporaries, by as much as the Melancholia of Dürer is separated from the Melancholia of Beham. La Mort du Vagabond is not a whit less suggestive in its contrast between the feebleness of the worn-out beggar now stretched out lonely on the pathside—his head raised, gasping, and his hat knocked away—and the force and fury of the storm that beats over dead tree and desolate common. The unity of tragic impression in homely life, preserved in this plate, will give it a permanent value among the great things of Art. La Mort et le Bûcheron is more tender, not more nor less poetical, but less weird; and nothing short of a high and vigorous imagination could have saved from chance of ridicule, in days in which the symbolical has long ceased to be an habitual channel of expression, this etching of the veiled skeleton of Death appearing to the old man still busy with his field-work, and beckoning him gently, while he, with simple and ignorant yet not insensitive face, touched with awe and surprise, looks up under a sudden spell it is vain to hope to cast off, since for him, however unexpectedly, the hour has plainly come. Of this very fascinating subject, there exist impressions from two different plates: one of the plates, and in some respects the better and more pathetic one—the one in which the figure of Death is gentler and more persuasive, and in which the face of the woodman is the more mildly expressive—having suffered an accident after only about a dozen impressions had been taken from it. The second was then executed, with something less at first than the success of the earlier one, so that the almost unique and very rare impressions of the plate—whatever may chance to be their money value—represent it to the least advantage. It was retouched and retouched, and at length with more of reward for the trouble than Legros has generally been able to meet with when laboriously modifying his work in the attempt to realise his conception more fully; until at last the enterprising management of L’Art was enabled to offer its readers for about three shillings a work of art not rare, indeed, but of exquisite beauty. The success of the first plate, which the acid had covered in a moment of neglect, had been almost refound.

A final word about the landscapes. As a painter of landscape M. Legros is little known, but there exist, I believe, in London one or two considerable collections of water colours which exhibit almost exclusively his art in landscape. As far as the etchings show it at all, it is of the most account when it is called in for the accompaniment of one of those impressive and doleful ditties I have just been speaking of. Sometimes, however, it is good without this mission and significance, as in the Pécheur, where a delicate effect of early morning is given with exquisite refinement. But at other times, in which the artist is dealing with landscape charged for him with no especial meaning, his very observation of it seems to have been lacking in interest and acuteness, as in the broad slope of grass by the stream-side in his big print Les Bûcherons—a whole surface of ground that is treated mechanically and without any worthy apprehension. And yet this print, despite certain unpleasantness, contains in the heads of the woodcutters some of his finest work. A much more sketchy subject, Paysage aux Meules, has greater unity of impression. Like a good deal of Legros’s landscape, it is distinctively French, this particular glimpse of field and farm and rounded hill reminding one of the wide-stretching uplands of the Haut Boulognais. Other landscapes are of England. Others, again, are neither of England nor of France, nor of any land which may be read of in the guide-book or visited by the enterprising tourist, but of that land alone that rises in the imagination of artistic men.

END