CHAPTER IV

THE FLOUR-MOTH (Ephestia kühniella) IN SOLDIERS’ BISCUITS

Where moth ... doth corrupt. (MATT. vi. 19.)

IT is not only those insects that destroy the continuity of our soldiers’ integument which play a part in war. It has been well said that an army marches on its stomach; and the admirable commissariat arrangements which have been so distinctive a feature of the British Expeditionary Force during the present war are the result of much patient care and attention during times of peace. I am in no position to discriminate, but I do believe that the admirable service of the A.S.C. and the R.A.M.C. is at least equal to the splendid record of those in the fighting-line.

Every one knows that recruits are frequently rejected for some defect in their teeth. A soldier, indeed, requires strong teeth, for his farinaceous food in the field is largely supplied to him in the form of biscuits—not that ‘moist and jovial sort of viand,’ as Charles Dickens described the Captain biscuit, but ‘hard-tack’ which challenges the stoutest molars.

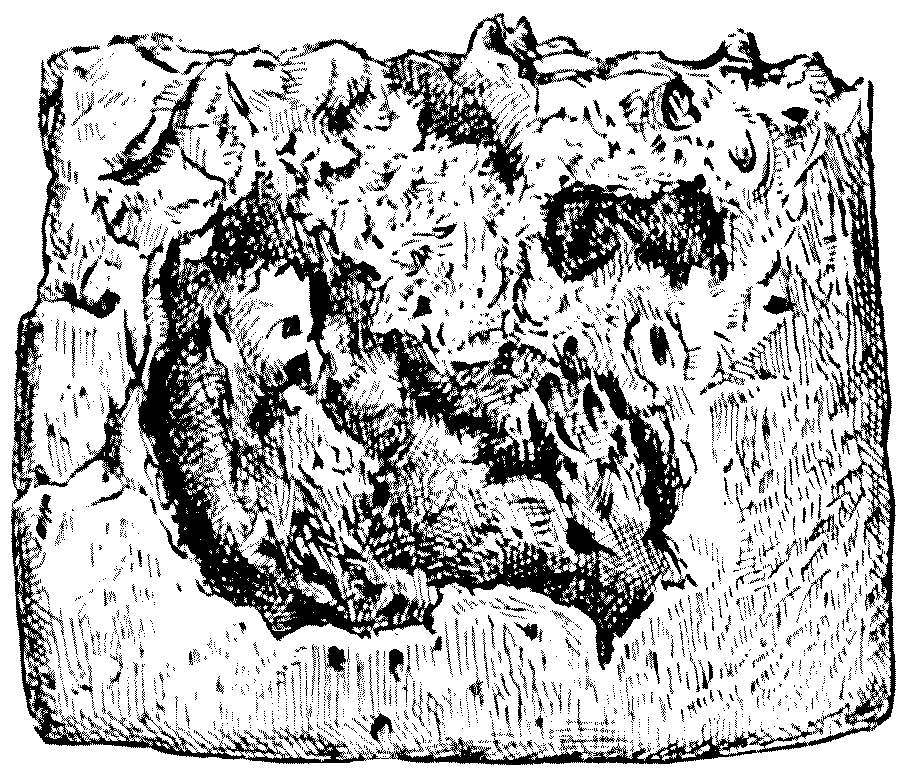

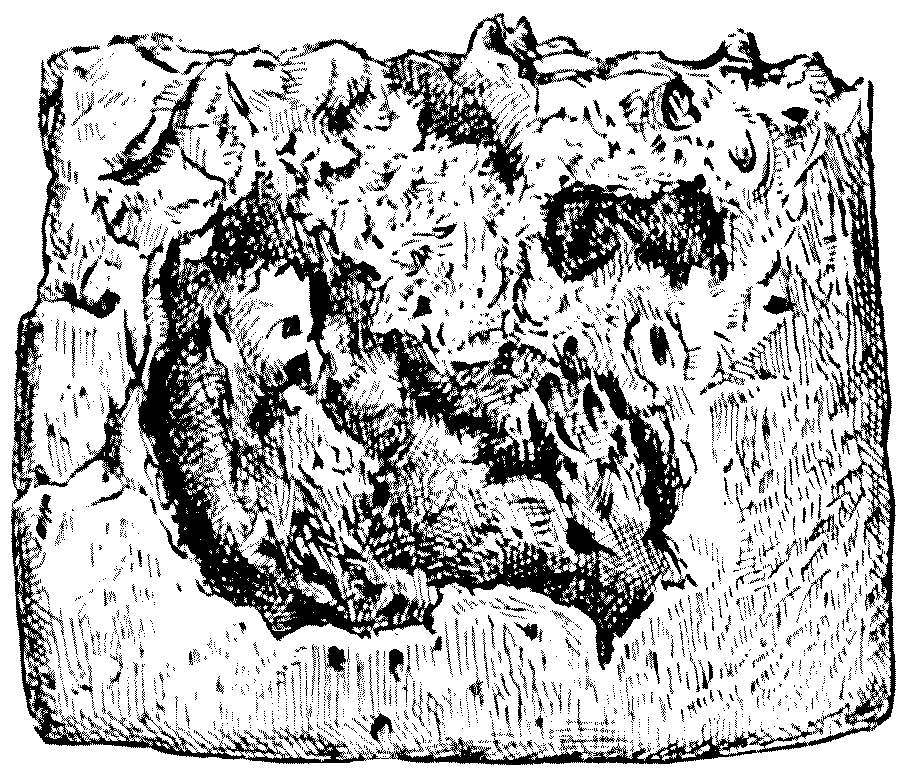

During the summer of 1913 the authorities of the British Museum at South Kensington arranged a very interesting but somewhat gruesome exhibit in their Central Hall. The exhibit consisted mainly of Army biscuits eaten through and through by the larva of a small moth and covered by horrible webs or unwholesome-looking skeins of silky threads.

FIG. 10.—Ephestia kühniella. Moth-infested biscuit.

Together with these derelict biscuits were certain long metallic coils and other apparatus used in investigating certain phases of the life-history of the moth and the manufacture of the biscuit. The exhibit illustrates an article which had recently appeared on the Baking of Army Biscuits, by Mr. Durrant and Lieut.-Colonel Beveridge, on the ‘biscuit-moth’ (Ephestia kühniella), a member of the family Pyralidae. The article recorded their efforts to arrive at a means of checking this very serious pest to service stores.[6]

The biscuit-moth (E. kühniella) was described two years before its larva had been noted damaging flour at Halle. There has always been a certain amount of international courtesy in attributing the provenance of insect pests to other countries; and when E. kühniella began, about ten years later, to attract attention in England it was believed to have been introduced from the United States, via the Mediterranean ports, in American meal. The American origin was, however, denied by Professor Riley, who, in a letter to Miss Ormerod, states, ‘I think I can safely say that this species does not occur in the United States.’ At the moment of writing these words Professor Riley was in the act of packing-up to leave Washington for Paris. Possibly he was excited, certainly he was inaccurate, for the species was then known to be prevalent in Alabama, North Carolina, and other States. In fact, to-day it is recorded throughout Central America and the Southern States, and in most of the temperate regions of the New World.

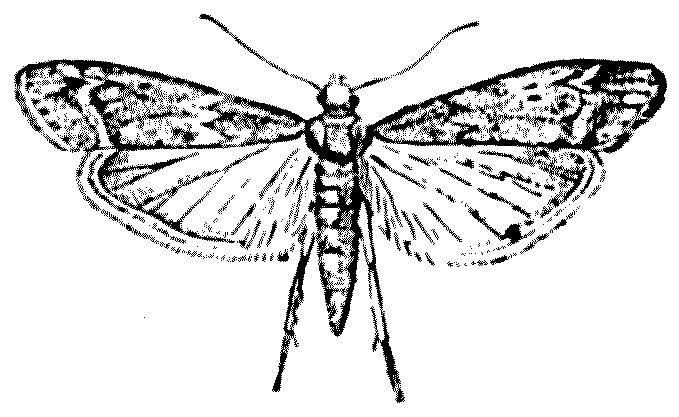

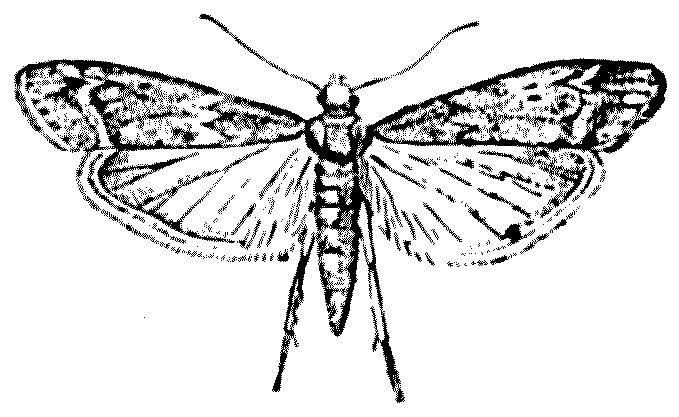

FIG. 11.—Ephestia kühniella. × 2.

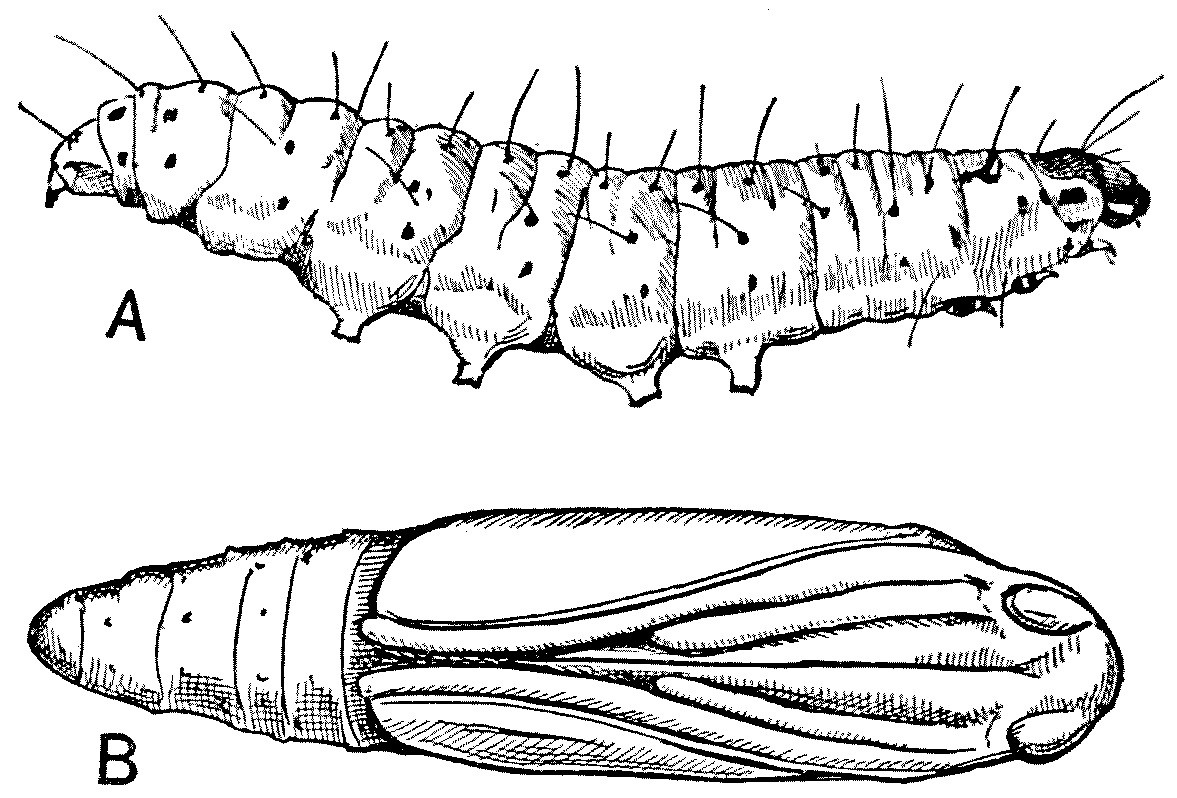

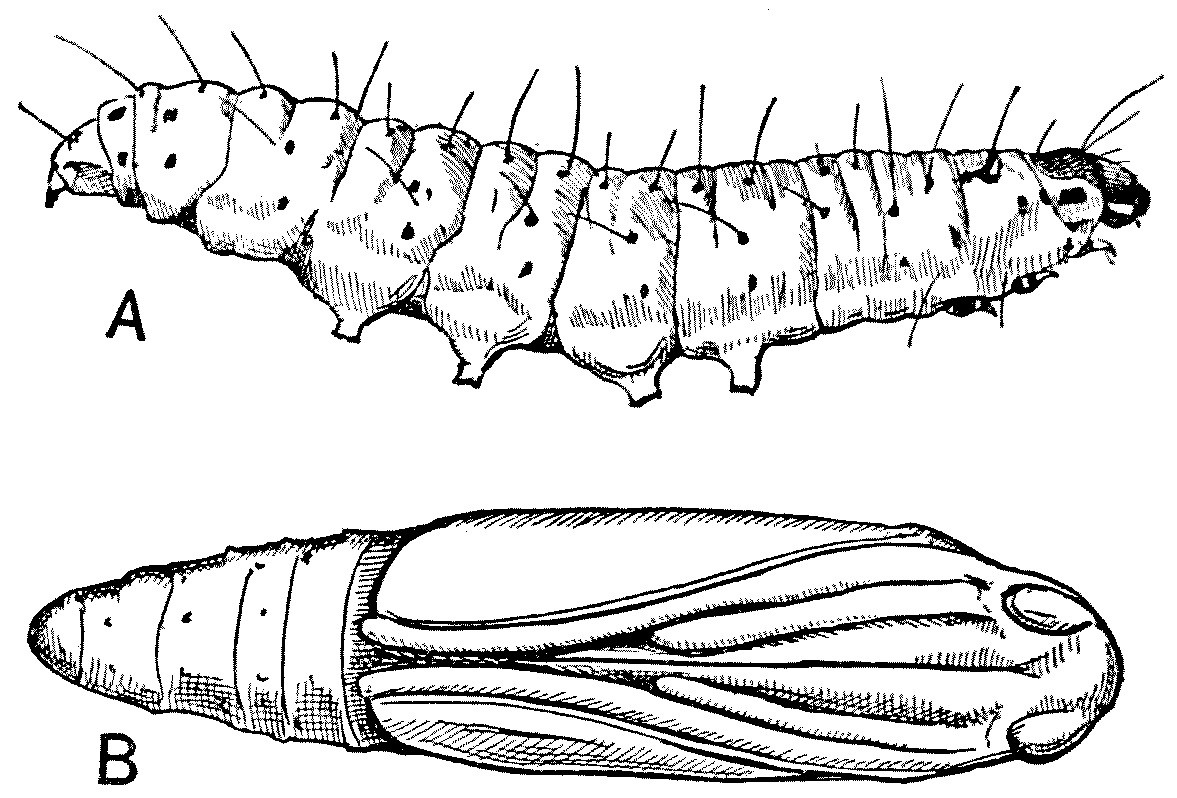

The moth itself is a rather insignificant, small insect, of a slatey-grey colour. Its eggs, rather irregular ovoids, are laid upon the biscuit into which the issuing larvae bore. These latter are soft and like most creatures which live in the dark, whitish, though with a tinge of pink; the head, however, is brown and hardened. The larva is constantly spinning silken webs or tissues, which in the most untidy way envelop the biscuit. It finally entombs itself in a whitish silken cocoon, and herein it ultimately turns into a chrysalis or pupa.

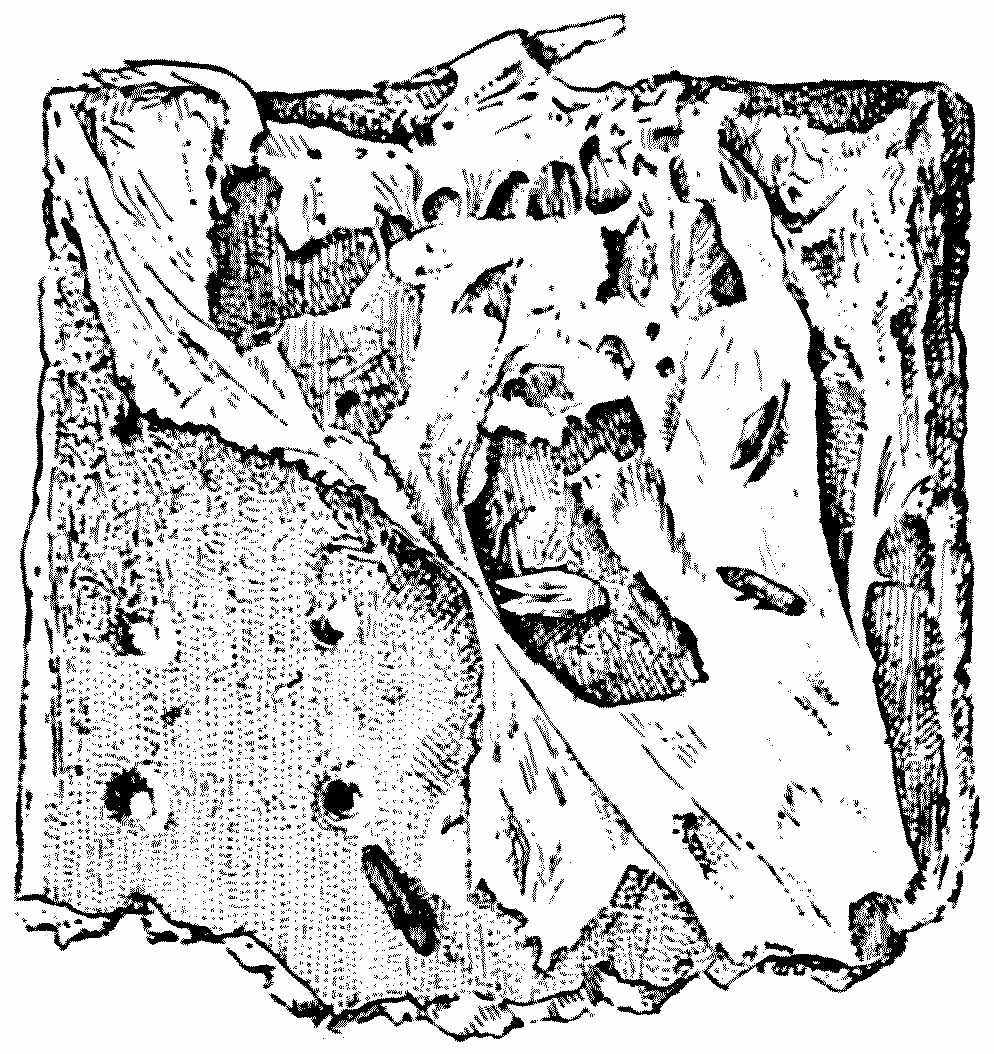

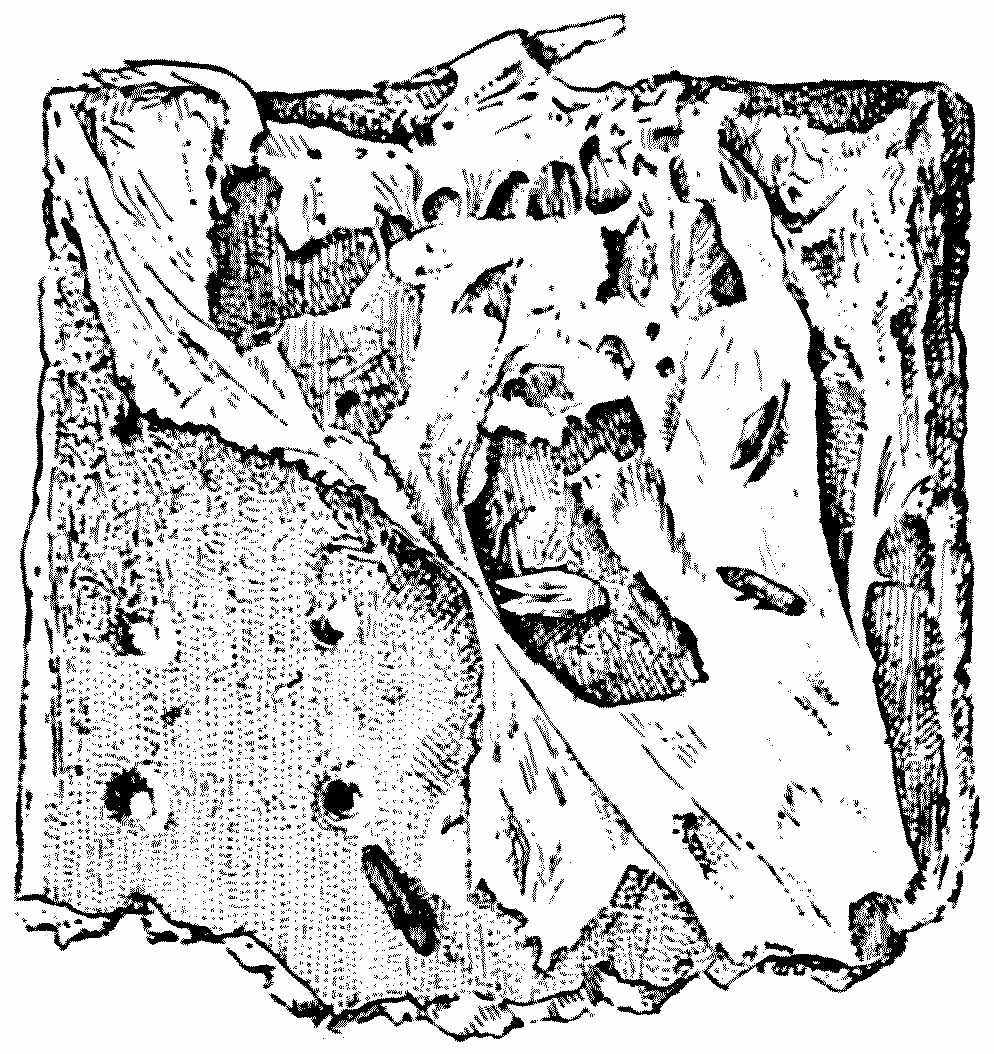

Another Pyralid moth—Corcyra cephalonica—makes similar unpleasant webs all over biscuits, rice, or almost any farinaceous food; but, since its larvae are unable to live unless there be a certain degree of moisture in its food, it is less injurious to baked food than the Ephestia, for whose larvae nothing can be too dry. Corcyra seems originally to be a pest of rice, and to have been introduced into Europe with Rangoon rice; but it readily alters its diet in new surroundings, and will live on almost any starchy stuff, if not too desiccated.

The problem that Lieut.-Colonel Beveridge and Mr. Durrant, of the British Museum, set out to solve was at what stage in the manufacture of the Army biscuits does our soldiers’ food become infested, and whether any steps could be taken to avoid or minimise such infestation.

FIG. 12.—Ephestia kühniella. A, Larva; B, pupa. Greatly magnified.

First, as to infestation. The biscuit must become infested either (1) at home before packing, (2) during transit, or (3) in the country where they are stored. The biscuits are packed in tins, hermetically sealed, and enclosed in wooden cases to prevent injury; it was therefore obvious that if insects could be found within intact tins it would be demonstrated at once that infestment must have taken place in the factories, and not subsequently.

FIG. 13.—Corcyra cephalonica. Moth-infested biscuit.

With a view to determine the origin of infestation sample tins were withdrawn from stocks at various stations abroad, and inspected by experts at Woolwich; and tins which, after careful examination, had been pronounced intact, were found to contain Ephestia kühniella and Corcyra cephalonica in various stages of development, thus proving conclusively that infestation had taken place in the factories before the tins were soldered, and indicating that preventive or remedial measures must be undertaken within the biscuit-making factories themselves.

It is obvious either that the heat to which the biscuit is subjected in the process of baking is insufficient to destroy any of the insect eggs present in the moist dough or that the moths and beetles deposit their eggs in or on the biscuits after baking, and during the process of cooling and of packing into the tins. Cooling before packing is necessary in order to allow the moisture in the centre of the biscuit to become evenly distributed throughout the ‘tissue’ of the biscuit. And it is during the time occupied in cooling and packing that the biscuit is exposed to the greatest risk of infestation; any risk occasioned by subsequent injury must be exceptional, and is probably negligible.

By a series of most ingenious experiments, the two investigators were able to determine the temperature in the centre of the biscuits during the various stages of its baking and cooling. Army biscuits are made from dough which contains about 25 per cent. of water. When stamped out they are placed in rows on the revolving floor of an oven, and are submitted to a high temperature for twenty minutes whilst they travel over a space of 40 feet. The dough at first contains, as we have said above, 25 per cent. of water, but during baking this is reduced to about 10 per cent., and the moisture now collects in the centre of the mass of the biscuit in consequence of the external hardening or ‘caramelisation,’ as it is called. The holes which are pricked in so many biscuits of course help to equalise the spread of the moisture throughout the biscuit.

Too little attention has been paid to the internal temperature of edibles which are being cooked. Very few people, for instance, have any conception of what is going on in the centre of a joint of meat whilst it is being roasted or boiled. After two hours’ boiling the temperature in the centre of a large ham has only risen to 35° C.; after six hours’ boiling to 65° C., and it is only after ten hours’ continuous boiling that 85° C. is reached. I have, I am sorry to say, no conception as to how long a ham ought to be boiled, but it is obvious that to be really effective against such parasites as Trichinella—the causa causans of trichinosis—the cooking of pork and ham should be more prolonged and thorough than seems to be customary. But that is another story.

However, to return to our biscuits. The Colonel and Mr. Durrant devised an ingenious instrument which determined the rising temperature at the centre of our Army biscuits whilst baking. When the tip of their recording apparatus lay within the moist area of the biscuit, the temperature registered was only a little over 100° C.; but when the tip of the instrument rested on the hard ‘caramelised’ portion much higher temperatures were observed—even as high as 125° C. Colonel Beveridge and Mr. Durrant were thus able to establish the fact that the temperatures of the biscuit were, during baking, such as to rule out the idea that the eggs of the biscuit-moth—which do not survive a temperature of 69° C. for twelve minutes—were deposited in the biscuit before cooking.

After the baking is completed the biscuits are cooled, and it is at this period that they are most exposed to risk of infestation by Ephestia kühniella. This insect is a well-known nuisance in Flour-mills. So persistent and numerous are these moths at times that they clog the rollers with their cocoons, and sometimes completely stop them. The webbing of the elevators in the mills gets covered with them and with their silky skeins, and then the elevators stop working. They mat together the flour and meal with their silken excreta, and so uniform is the temperature of the Mill, and so favourable to the life of the insect, that they complete their life-cycle in this country in two months, and in the warmer parts of America even more rapidly. In well-heated mills the proceeding is continuous, so that six generations at least may be produced each year.

The most efficient method of getting rid of this pest of the Army biscuit is a complete and thorough fumigation of the infested premises with carbon bisulphide. But, as this substance is not only poisonous but inflammable, it is well to get a chemist to undertake the proceeding, and also to notify the Insurance Company. Fumigation by sulphur ruins the flour. Another remedial measure is that of turning the steam from the boilers on to all the infected machinery and walls.

That this destruction of the Army biscuit is a matter of considerable importance is shown by the fact that biscuit-rations exported to the colonies in hermetically sealed tins have become quite unfit for consumption, and this destruction has been noted in places as far distant from each other as Gibraltar, the Sudan, Mauritius, Ceylon, South Africa, and Malta. That it is also an old trouble is shown by the following quotation from the diary which Sergeant Daniel Nicol, of the 92nd (the Gordon Highlanders), kept during the expedition to Egypt in 1801:—

Some vessels were dispatched to Macri Bay for bullocks, and others to Smyrna and Aleppo for bread which was furnished us by the Turks—a kind of hard dry husk. We were glad to get this, as we were then put on full rations, and our biscuits were bad and full of worms; many of our men could only eat them in the dark.[7]

With regard to the actual baking of the biscuit, Colonel Beveridge and Mr. Durrant suggest that the temperature conditions during the process of cooling should be made as unfavourable as possible for the moths by introducing screened cool air, which can be forced in at one end of the cooling-chamber and sucked out at the other. Could such a scheme be adopted it would be difficult, if not impossible, for the moths to lay their eggs, and the biscuit would thus be more rapidly cooled. In any case it should not be difficult to ensure that the cooling takes place in some chambers which are practically free from these destructive moths.