CHAPTER III

THE FLEA (Pulex irritans)

Marke but this flea, and marke in this,

How little that which thou denyst me is;

It sucked me first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea our two bloods mingled bee.

(DR. DONNE.)

THE fact, now fully established, that the bubonic plague is conveyed to man from infected rats, or from infected men to healthy men, by fleas has taken that wingless insect out of the category of those animals which it is indelicate to discuss.

No doubt, as Mr. Dombey says, ‘Nature is on the whole a very respectable institution’; but there are times when she presents herself in a form not to be talked about, and until a few years ago the flea was such a form. Hence, few but specialists have any clear idea either of the structure or of the life-history or of the habits—save one—of the flea.

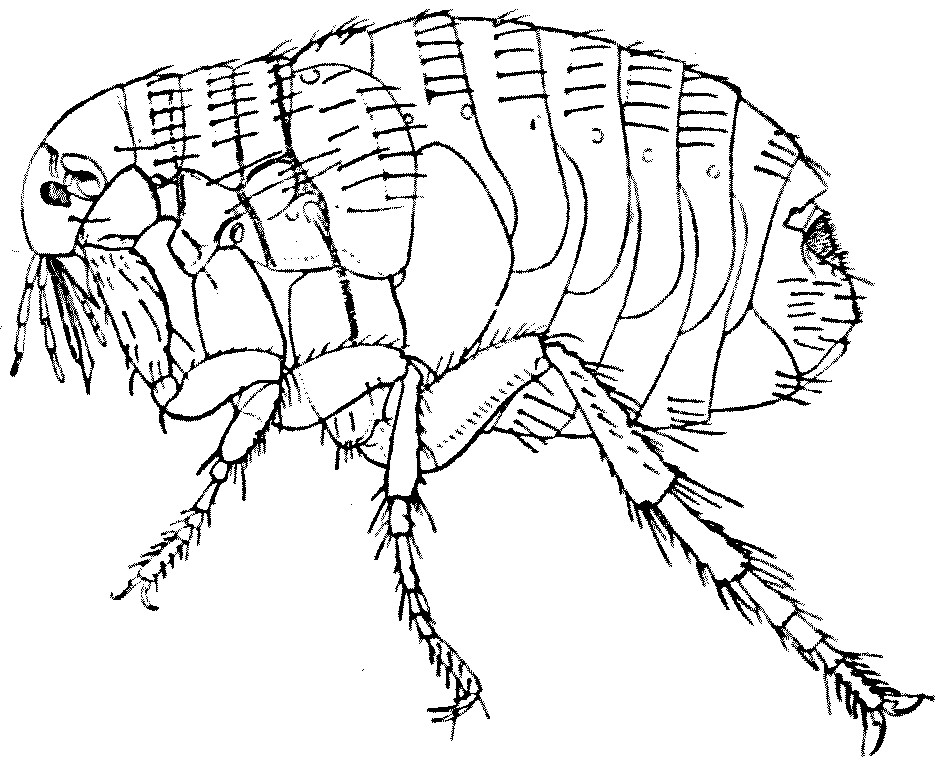

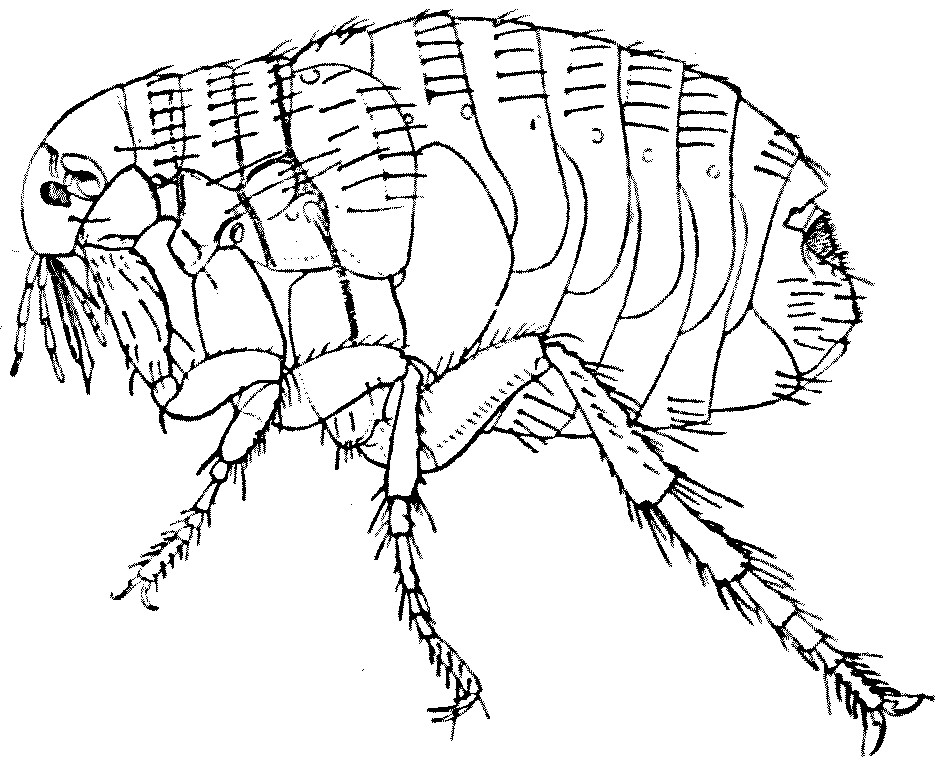

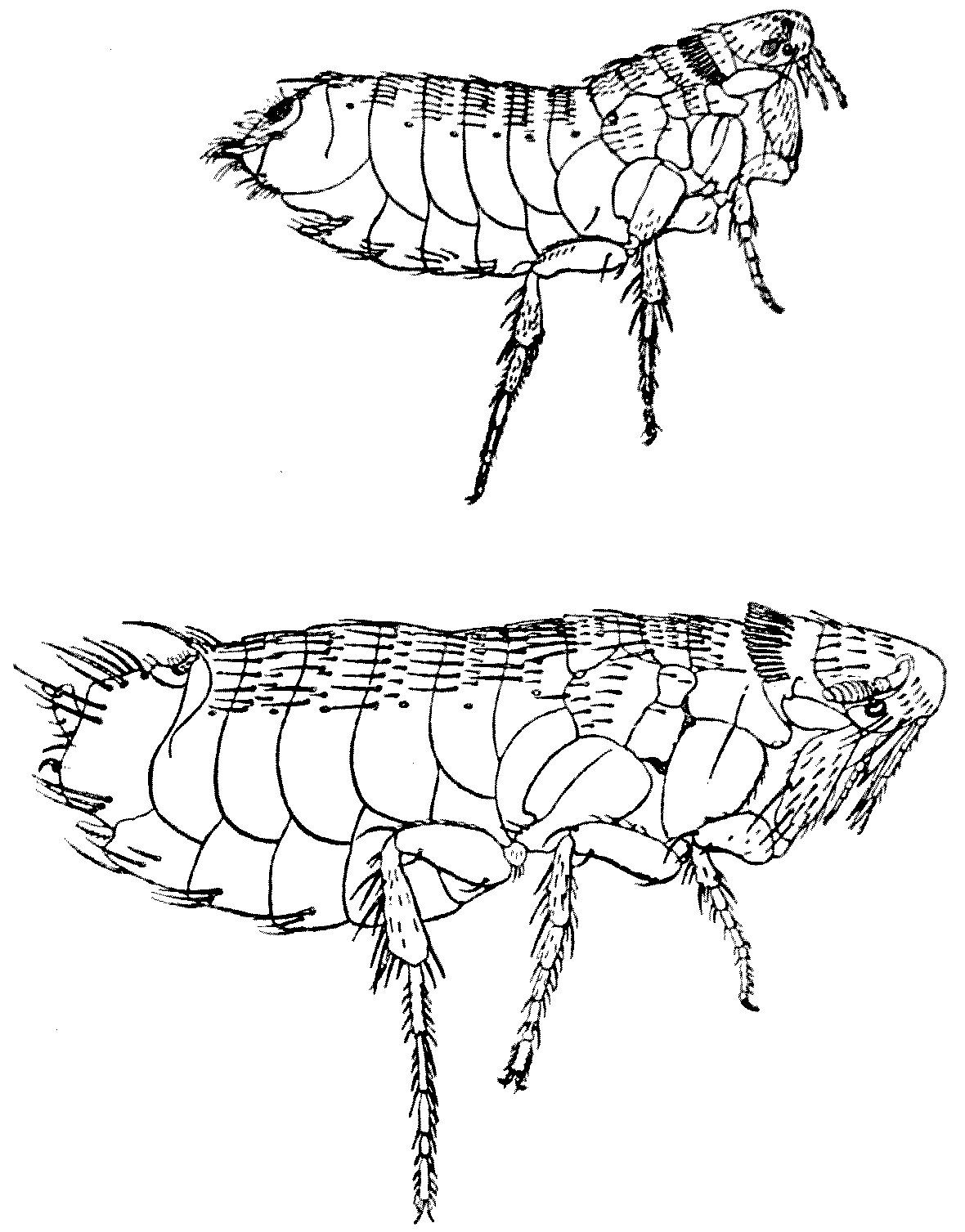

FIG. 6.—Pulex irritans, female. The legs of the left side only are shown. Enlarged. (After a drawing by A. Dampf.)

Fleas are temporarily parasitic on many mammals and birds, but some mammals and some birds are much freer from fleas than others. As the flea is only on its host for part of the time, it has to put in the rest of its existence in some other place, and this, in the case of the human flea, is usually the floor, and in the case of bird-fleas the nest; from these habitats they can easily regain their hosts when the latter retire to rest. But large numbers of Ungulates—deer, cattle, antelopes, goats, wild boars—sleep in different places each recurrent night, and to this is probably due the fact that, with the exception of two rare species—one taken in Northern China and the other in Transcaucasia—the Ungulates have furnished descriptive science with no fleas at all. Both of these Ungulate fleas are allied to the burrowing-fleas or ‘chigoes.’

I know none of my readers will believe me when I say that the same is true of monkeys; but I do this on the undoubted authority of Mr. Harold Russell, who has recently published a charming little monograph on these lively little creatures. Monkeys in nature are cleanly in their habits; and although in confinement occasionally a human flea attacks them, and although occasionally a chigo bores into the toes of a gorilla or chimpanzee, ‘speaking generally, it may be said that no fleas have been found truly parasitic on monkeys.’ Whatever the monkeys are looking for, it is not fleas. What they seek and find is in effect little scabs of scurf which are made palatable to their taste by a certain sour sweat.

As a rule, each host has its own species of flea; but though for the most part Pulex irritans is confined to man it is occasionally found on cats and dogs, whilst conversely the cat- and dog-fleas (Ctenocephalus felis and Ct. canis) from time to time attack man.

The bite of the flea is accompanied by the injection of the secretions of the so-called salivary glands of the insect, and this secretion retards the coagulation of the victim’s blood, stimulates the blood-flow, and sets up the irritation we have all felt.

It is only a few years ago that the spread of bubonic plague was associated first with rats, and then with rat-fleas; and at once it became of enormous importance to know which of the numerous species of rat-flea would attack human beings. The Hon. Charles Rothschild, who has accumulated a most splendid collection of preserved fleas in the museum at Tring, had some years ago differentiated from an undifferentiated assemblage of fleas a species first collected in Egypt, but now known to be the commonest rat-flea in all tropical and sub-tropical countries. This species Xenopsylla cheopis—and to a lesser extent Ceratophyllus fasciatus—unfortunately infests and bites man. If they should have fed upon a plague-infected rat and subsequently bite man, their bites communicate bubonic plague to human beings. Plague—the Old English ‘Black Death’—is a real peril in our armies now operating in Asia and in certain parts of Africa.

Just as some fleas attack one species of mammal or bird and avoid closely allied species, so the human flea has its favourites and its aversions. There is a Turkish proverb which says ‘an Englishman will burn a bed to catch a flea,’ and those who suffer severely from fleabites would certainly do so. The courage of the Turk in facing the flea, and even worse dangers, may be, as the schoolboy wrote, ‘explained by the fact that a man with more than one wife is more willing to face death than if he had only one.’ But there are persons even a flea will not bite. Mr. Russell has reminded us in his Preface of the distinguished French lady who remarked, ‘Quant à moi ce n’est pas la morsure, c’est la promenade!’

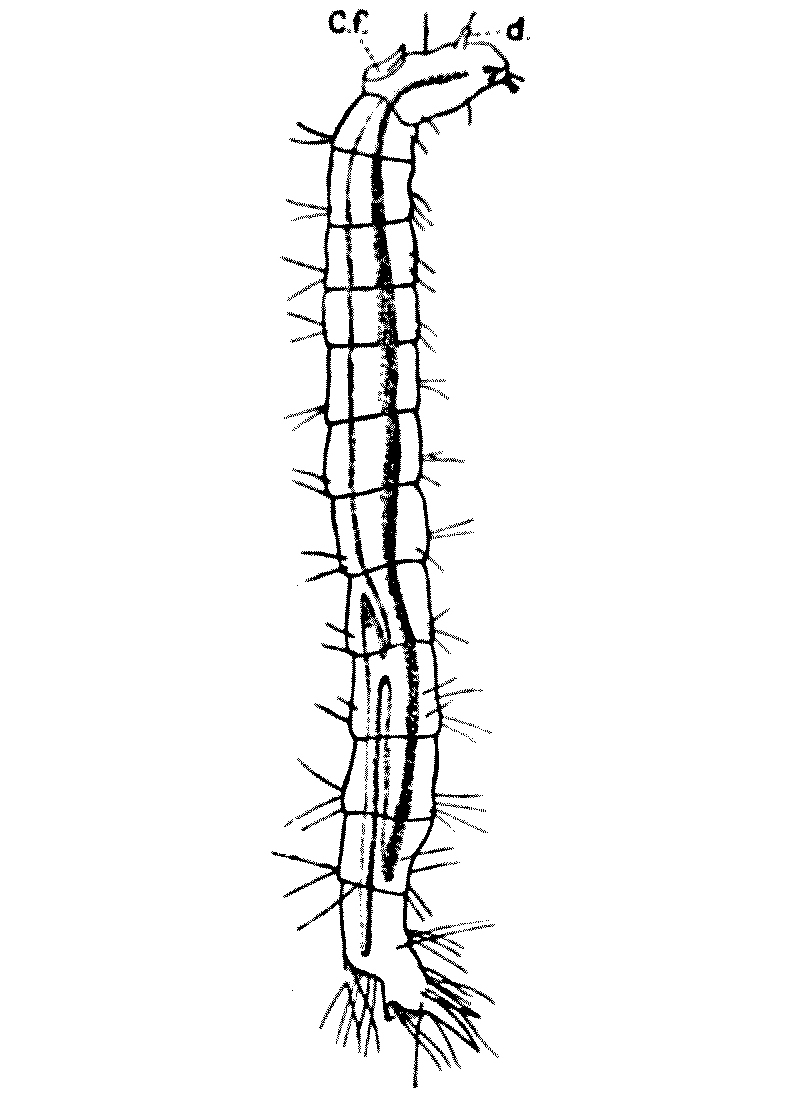

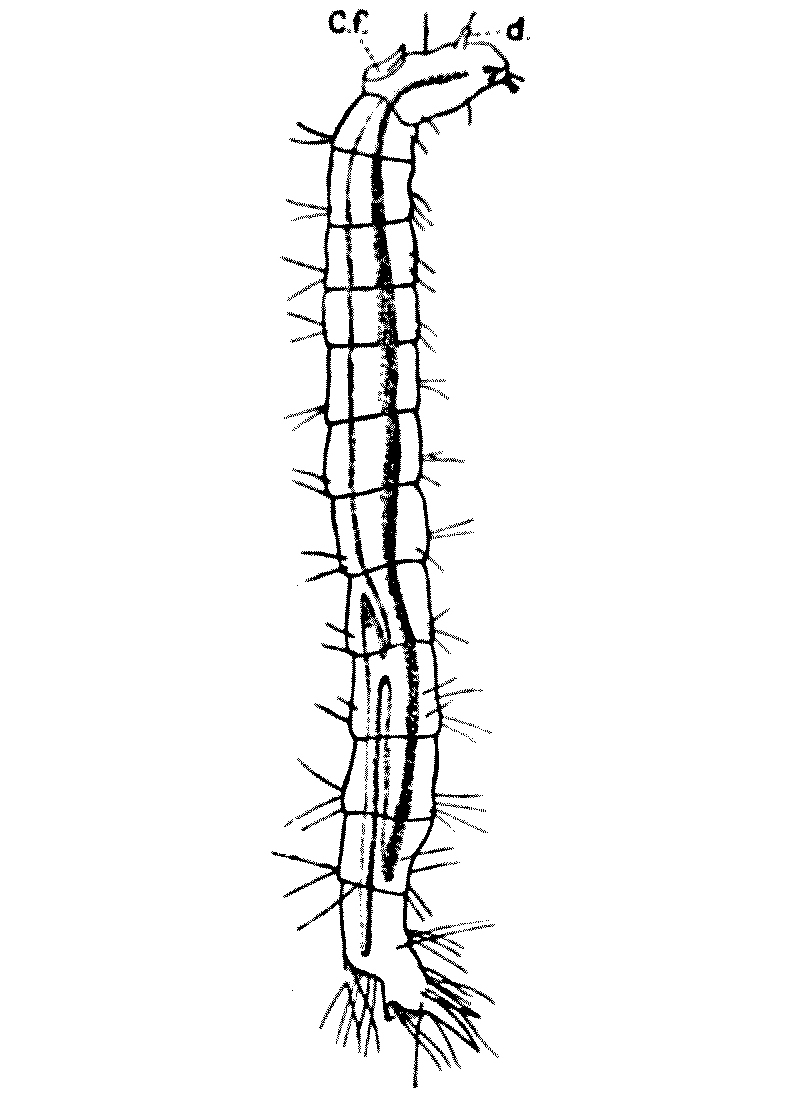

FIG. 7.—Larva of Pulex irritans. C.f. frontal horn; d, antenna. Enlarged. (After Brumpt.)

There are one or two structural features in a flea which are peculiar: the most remarkable being that, unlike most other insects, it is much taller than it is broad. As a rule, insects—such as a cockroach, the bed-bug, or a stag-beetle—are like skates, broader than they are thick, but the flea has a laterally compressed shape, like a mackerel or a herring. Then, again, the three segments or rings which come after the head are not fused into a solid cuirass or thorax as they are in the fly or the bee, but they are movable one on the other. Finally, it is usual in insects for the first joint of the leg to be pressed up against and fused with those segments of the body that bear them; but in the flea not only is this joint quite free, but the body-segment gives off a projection which stretches out to bear the leg. Thus the legs seem, unless carefully studied, to have an extra joint and to be—as indeed it is—of unusual length. They certainly possess unusual powers of jumping—as Gascoigne, a sixteenth-century poet (1540–78) writes, ‘The hungry fleas which frisk so fresh.’

The male, as is so often the case amongst the Invertebrata, is much smaller than the female. The latter lays at a time from one to five minute, sticky, white eggs, one-fortieth of an inch long by one-sixtieth broad. They are not laid on the host, but in crevices between boards, on the floor, between cracks in the wainscoting, or at the bottom of a dog-kennel or in birds’ nests. Mr. Butler recalls the case of a gentleman who collected on four successive mornings sixty-two, seventy-eight, sixty-seven, and seventy-seven cat-fleas’ eggs from the cloth his cat had slept upon. Altogether 284 eggs in four nights! The date of hatching varies very much with the temperature. Pulex irritans takes half as long again—six weeks instead of four—to become an adult imago in winter than it does in summer. But in India the dog-flea will complete its cycle in a fortnight.

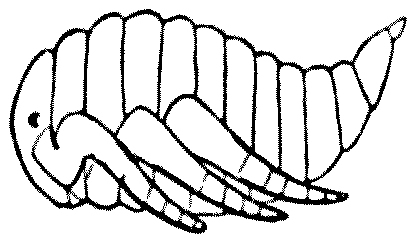

FIG. 8.—Pupa of flea. (After Westwood.)

When it does emerge from the egg the larva is seen to be a whitish segmented little grub without any limbs, but with plenty of bristles which help it to move about; this it does very actively. There are two small antennae and a pair of powerful jaws, for the larva does not take liquid food, but eats any scraps of solid organic matter which it comes across: dead flies and gnats are readily devoured. The larva casts its skin several times, though exactly how often it moults seems still uncertain.

After about twelve days of larval existence it spins itself a little cocoon in some sheltered crevice, and turns into a whitish inert chrysalis or pupa. During its pupal existence it takes, of course, no food, but it grows gradually darker, and after undergoing a tremendous internal change, breaking down its old tissues and building up new ones, the chrysalis-case cracks and the adult flea jumps out into the world.

There are many superstitions about fleas. March 1st is in some way connected with them, and in the south of England the house-doors are in some villages closed on that day under the belief that this will render the building immune for the following twelve months. The most successful insecticide is said to be prepared from Pyrethrum, which is grown in the Near East in large quantities for this purpose. But the Austrians, the Serbians, and the Montenegrins are fighting over the chief world-supply of this plant—possibly without knowing what they are doing—and ‘Insektenpulver’ is bound to go up in price. Wormwood (Artemisia) is also recommended.

While wormwood hath seed, get a handfull or twaine,

To save against March, to make flea to refraine;

When chambere is swept and wormwood is strowne,

No flea for his life dare abide to be known.

(TUSSER.)

The author of ‘A Thousand Notable Things’ suggests the following plan, but, so far, I have not met anyone who has tried it: ‘If you mark where your right foot doth stand at the first time that you do hear the cuckow, and then grave or take up the earth under the same; wheresoever the same is sprinkled about, there will no fleas breed. I know it hath proved true.’

Plastering a floor with cow-dung is a common practice in South Africa, and seems to be an efficacious means of keeping down fleas. Dr. R. J. Drummond tells me that all natives of India and Ceylon spread an emulsion of cow-dung in hot-water over the floors and the walls of their dwellings to keep out fleas. This has been done from immemorial times, and is effective. The efficacy of the emulsion in keeping fleas away has been doubted, and so I am glad to quote a few lines from a kind letter sent me by Dr. P. A. Nightingale of Victoria, Southern Rhodesia, which put the matter in a happy light:—

I think the correct facts are these: the floors of certain houses, huts, &c., throughout the South African veld are made of ant-heap earth, moistened and beaten hard and flat with sticks. This floor is then smeared at regular intervals—say, every ten days—with fresh cow-dung, when the room becomes fresh and sweet (!) and free from insects.

However, before the smearing can be done it is necessary to turn all the furniture out of the room and to sweep it thoroughly; after the smearing, the doors and windows are left open for drying purposes.

Hence, I think that the absence of fleas in such quarters is really due to general cleanliness, sunlight, and fresh air, and not to any special virtue in the cow-dung.

I am, however, sure that the smearing of the floor at frequent intervals does keep many pests down by filling up, and temporarily sealing, the numerous cracks in the floor where fleas, &c., reside and breed in vast numbers.

Huts—especially unused ones—not smeared for many weeks contain (approximately) several thousands of fleas, white ants, centipedes, and scorpions to the square inch, when the only treatment is to cleanse the walls and floor with cyanide solution, or burn the whole place down.

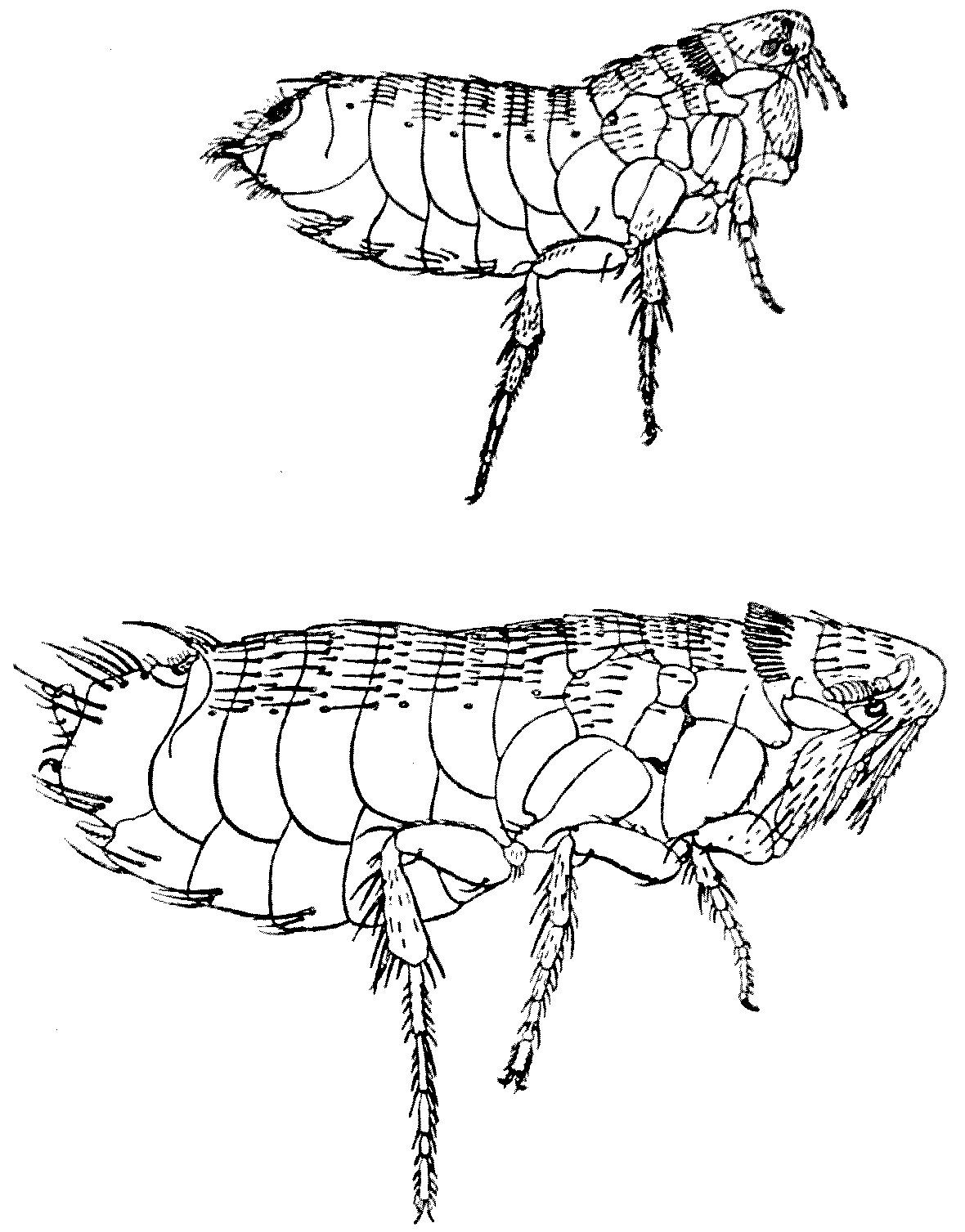

FIG. 9.—Ceratophyllus gallinulae. Male (above) and female (below). Drawn to scale and both highly magnified. These specimens, taken from a grouse, are of the same genus as one of the plague-conveying fleas.

From long experience, I am very nearly insect proof; but cannot stand the myriads of fleas I occasionally have to sleep with in a hut of the above description—especially just before the rains set in, when additional veld pests come into the huts for shelter.

We must, in the long run, treat fleas seriously. Although the Pulex irritans is a very common insect, the greatest living authority on fleas tells me it has never been accurately drawn. We have Blake’s ‘ghost of a flea’; but what did Blake know of entomology? In distinguishing one flea from another—fleas which may attack man and fleas which have hitherto declined to do so—every hair, every bristle, counts. Hence, I illustrate this article with accurate outlines of certain fleas found on the grouse, and for whose accuracy I can vouch (Fig. 9).

As I have said above, a certain rat-flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) and another (Ceratophyllus fasciatus) undoubtedly convey the bacillus of plague from rats and other Murinae to man and vice versa. The Bacillus pestis is unlikely to establish itself in the present war in Europe, but Quién sabe? The Black Death of 1349–51 was conveyed by fleas, and so was Pepys’s Plague of 1665. Plague—flea-borne, we must remember—is still endemic in places as near Europe as Tripoli, and in numerous centres in Asia. Not a disease altogether to be neglected, since the spread of war to the Near East, but still not very threatening in Europe in the twentieth century.