CHAPTER VII

MITES

PART I

THE HARVEST-MITE (Trombidium)

Natura in minimis maxime miranda.

(LINNAEUS.)

WE do not know what life is, but we can at any rate record its manifestations; and we know that it is always associated with an extremely complex substance called by Purkinje ‘protoplasm.’ This substance Huxley described as ‘the physical basis of life.’ Protoplasm, though we know of what elements it is composed, defies accurate analysis, and, indeed, is never the same for two minutes together. It is constantly changing, it is in a state of flux and is, in effect, a stream into which matter is continuously entering and continuously leaving.

Protoplasm may be living, or it may be dead; and when dead it soon undergoes dissolution; but there is no life without protoplasm. Somewhere or other Dr. David Sharp has stated that of the total amount of protoplasm ‘in being’ in the world, the active volume of the life-material of our globe, at least one-half is wrapped up in the body of insects. But insects only form one sub-group out of the several which make up the great group Arthropoda, or those animals which are distinguished from others by possessing externally jointed legs—that is, jointed appendages. This group includes also the Crustacea, the multi-segmented Centipedes, and the Arachnids or spider-like animals.

Insects, like aeroplanes, dominate the air; Crustacea, like submarines, inhabit the water; the poet has passionately asked:—

Ah! who has seen the mailèd lobster rise,

Clap her broad wings and soaring claim the skies?

But the answer, in the language of those curious mammals the politicians, is ‘in the negative.’ Crustaceans are essentially aquatic. On the other hand, centipedes and spiders are earth-loving animals but some have unhappily developed parasitic or pseudo-parasitic habits.

The last-named sub-group, the Arachnids, comprise many subdivisions. There are the spiders, the harvest-men, the scorpions, the king-crabs, and so on. But one of the most numerous of the subdivisions of the group are the mites and ticks (Acarina). I have for years been trying to find some organ or structure shared by insects and mites and ticks, and not found in any other group of arthropods. If I could do this I would invent a long polysyllabic word—with lots of Greek in it—which would really be a short way of designating those arthropods which convey disease to man.

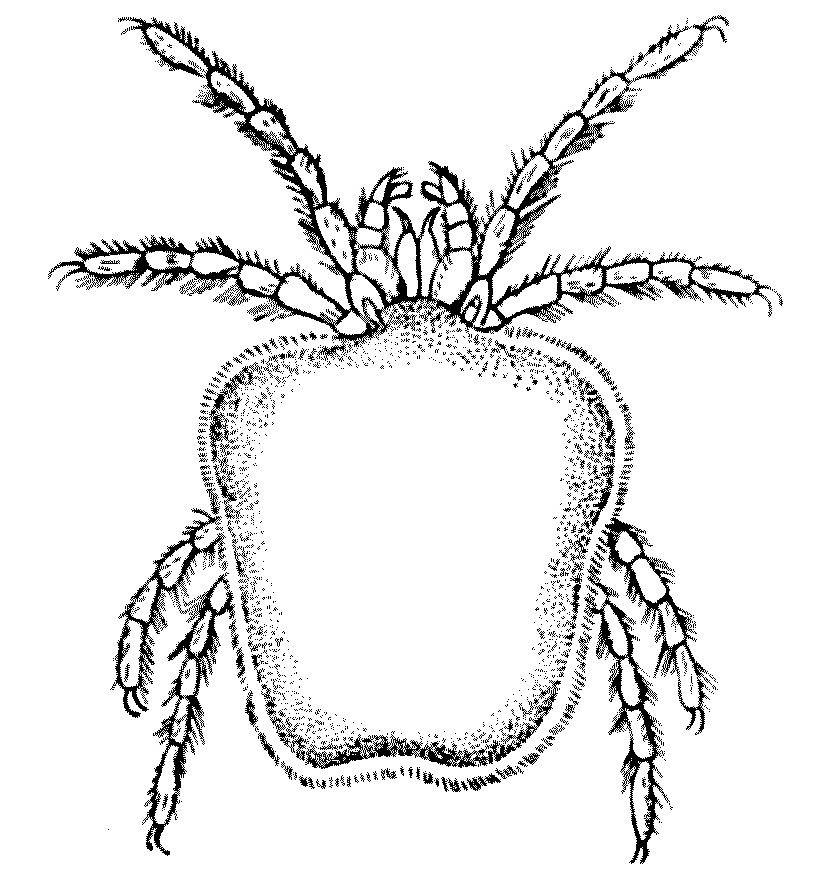

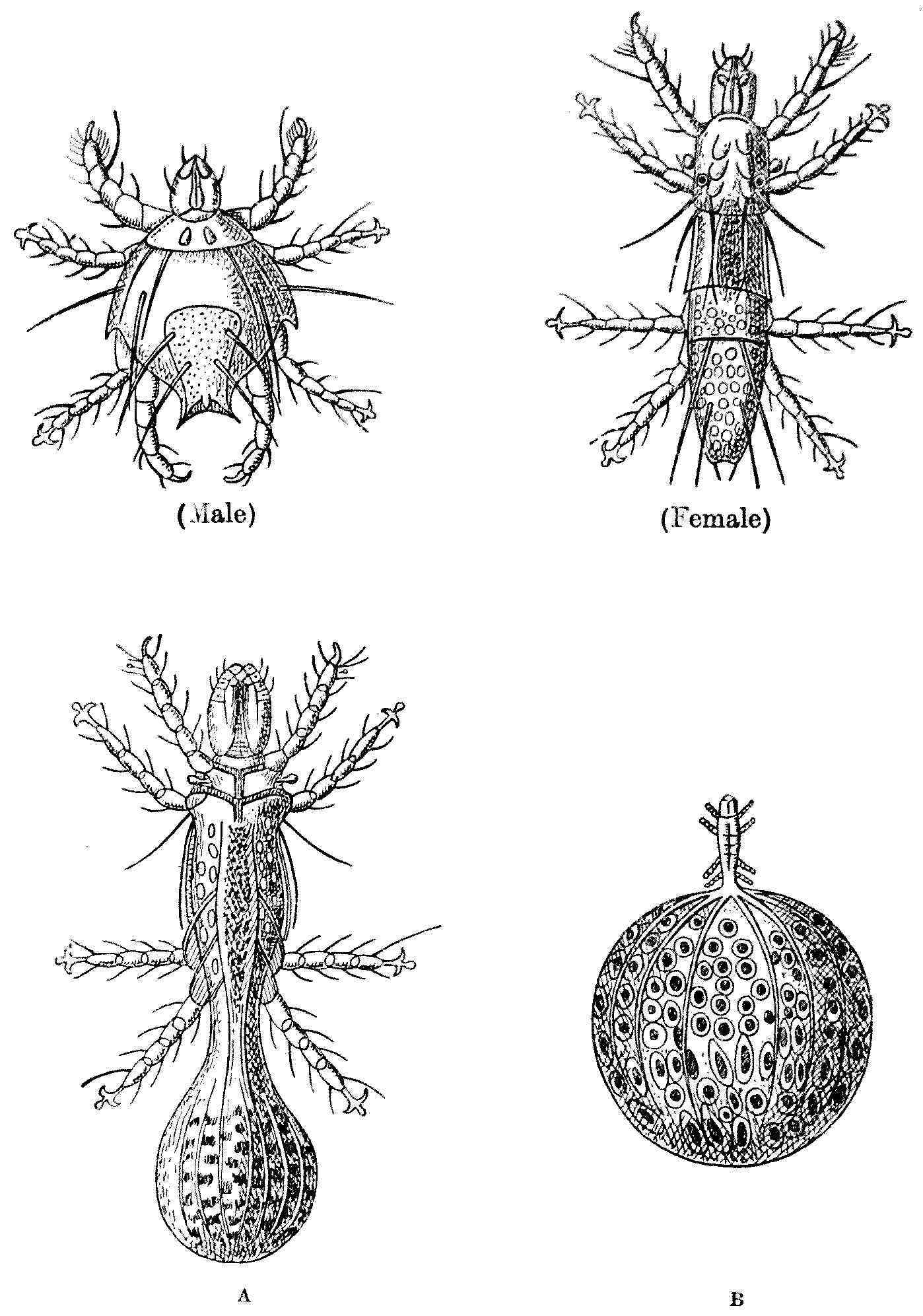

FIG. 29—Trombidium holosericeum. Female, dorsal view. × 20. (After Railliet.)

The acarines are for the most part small, and they differ from spiders in having no waist. In fact, the three divisions into which the body of an arthropod is normally divided—head, thorax, and abdomen—are indistinguishable in mites, the body forming an unconstricted whole. As a rule, these little creatures breathe, as do insects, by tracheae, or, if these be absent, by the general surface of the body. They live for the most part on vegetable and animal juices, and their mouth-parts are, as a rule, piercing and suctorial; but in some species the appendages of the mouth are capable of biting as well as piercing. The adults have typically eight legs. The larval stages are very numerous, and at times six distinct moults of the skin are recognisable. With few exceptions the larva emerges from the egg as a six-legged creature. In fact mites undergo a metamorphosis which varies in complexity and in completeness in different groups, and it is often one of the larval stages which causes the greatest trouble to man.

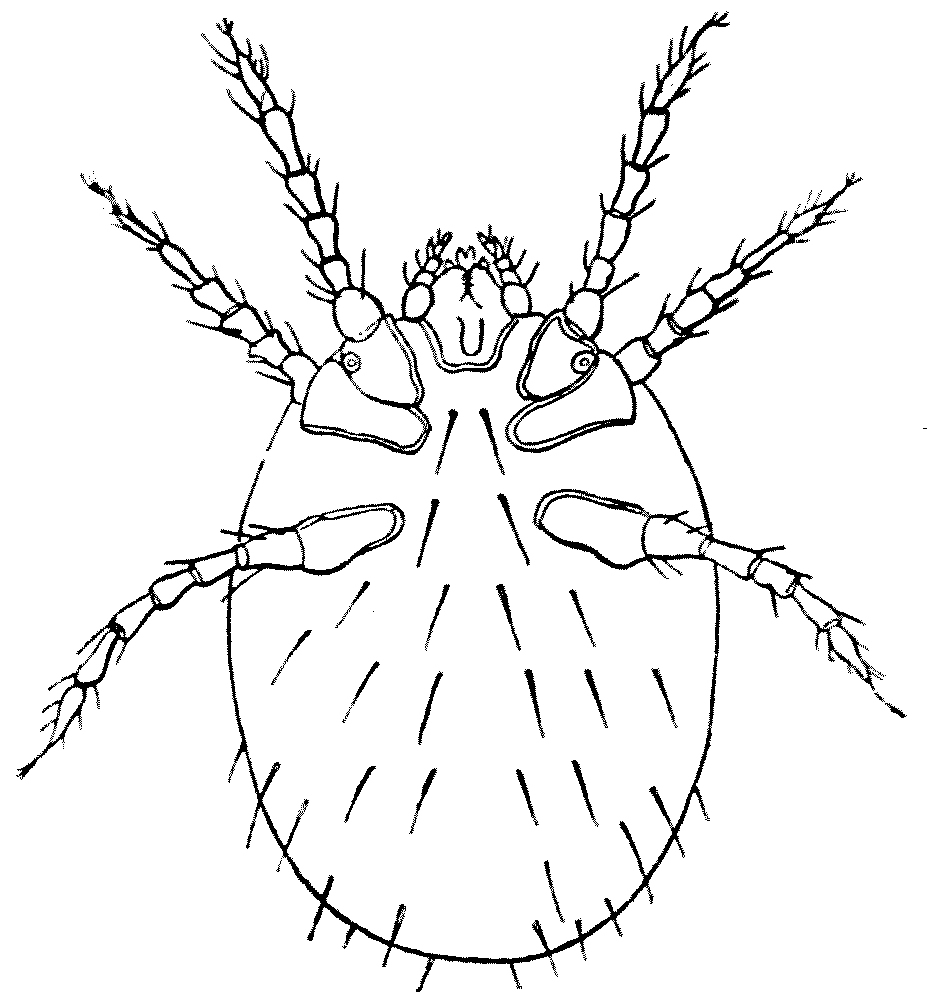

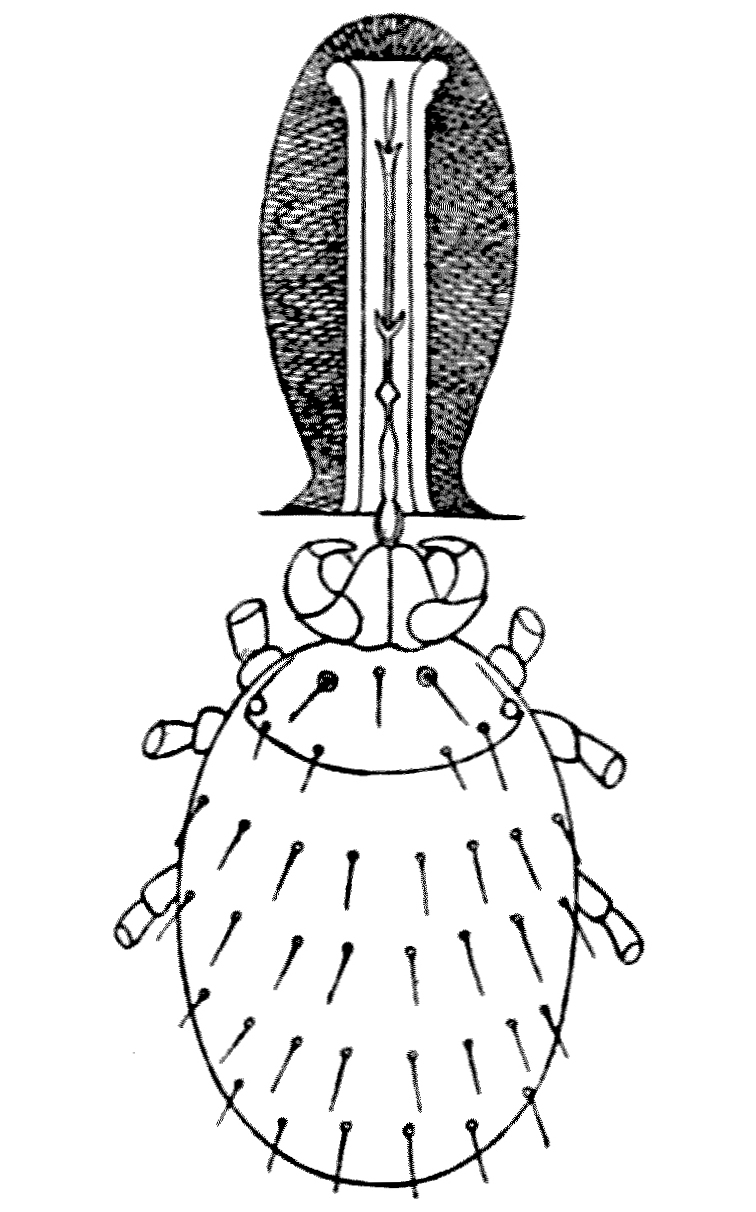

FIG. 30.—Leptus autumnalis = larva of Trombidium holosericeum. Ventral view. × 100. (After Railliet.)

One of these six-legged larvae has been long known as the harvest-mite, under the name of Leptus autumnalis. But this is not a real species, and there is still considerable confusion as to what the exact status of Leptus autumnalis, the harvest-mite, is. Probably the larvae of several species are involved, but it seems pretty certain that in many cases the larvae will grow up into specimens of the genus Trombidium holosericeum, though a certain and at present unknown percentage of the larvae will grow up into Trombidium something-or-other-else.

They are minute bright-scarlet little creatures—the Cardinals of the Mite world—of a beautiful satiny red, decorated here and there with blackish spots. The body of the adult is somewhat square, tapering slightly to the hinder end. Both legs and body are covered with red hairs. The eyes are borne on little stalks—like lighthouses. The legs have six joints and end in two little claws. The male is usually smaller and more feeble than the female, the latter reaching a length of 3 mm. to 4 mm. The adults are commonly met with in the spring or commencing summer. Apparently, they nourish themselves on vegetable sap. The larval form of this species[11] is undoubtedly one of the forms confused under the now discarded name of Leptus autumnalis. When starving, the body is orbicular in outline, but it becomes oblong when it is fed, and in this case it may attain a length of ½ mm. Its colour is of a deep orange.

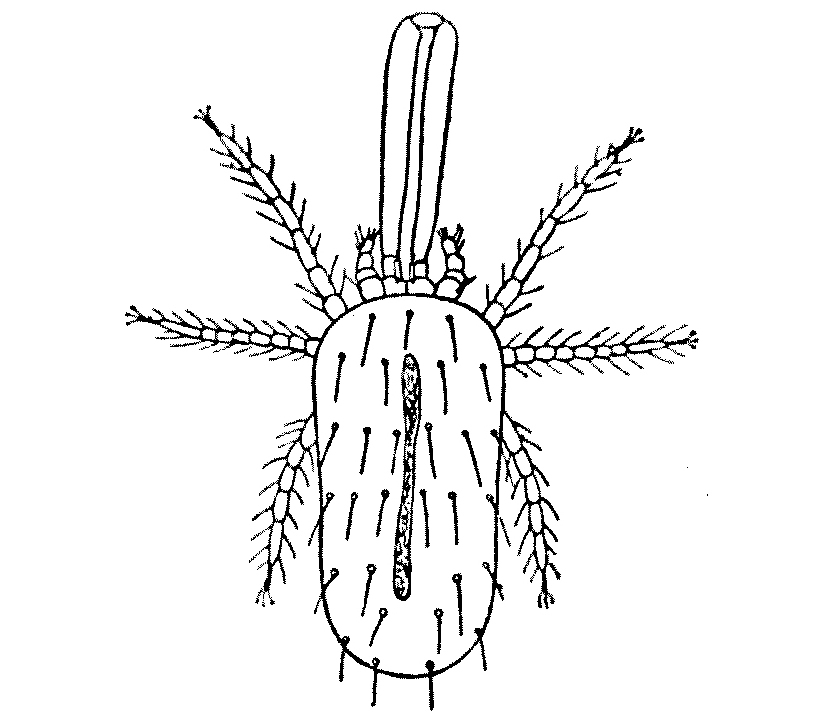

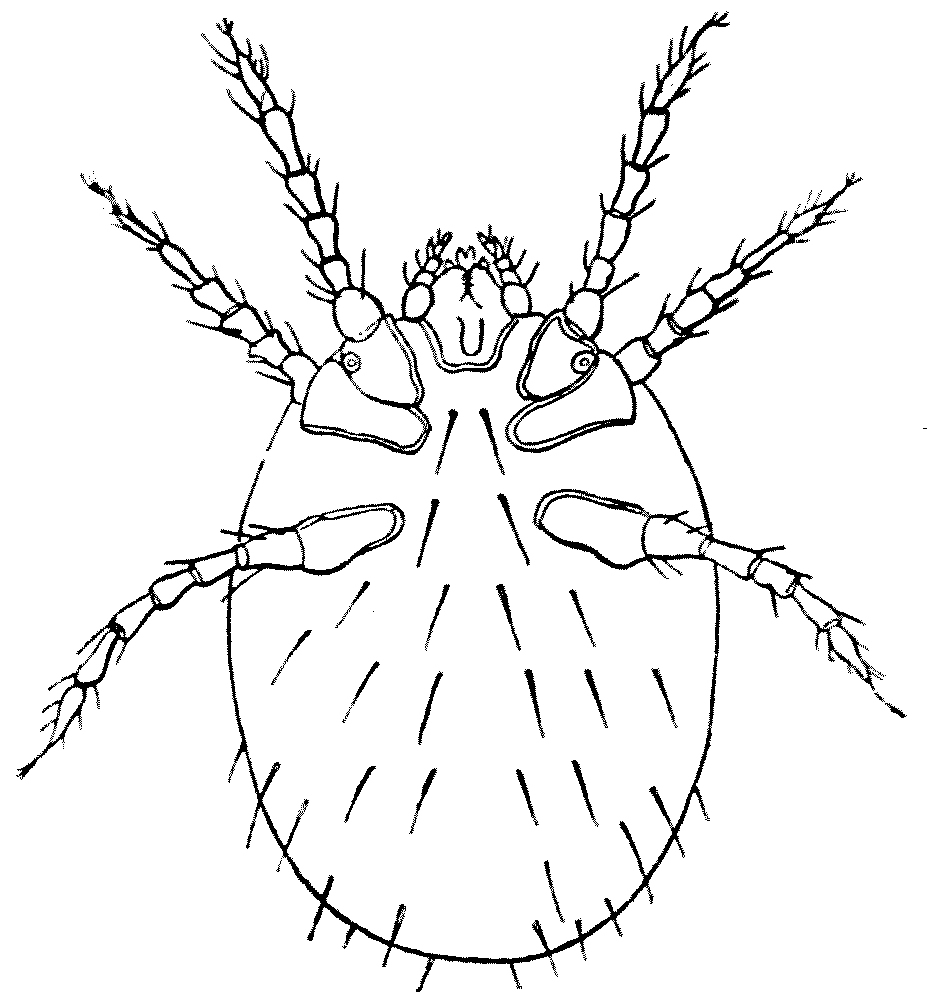

FIG. 31.—Leptus autumnalis, with the so-called proboscis. Magnified. (After Gudden.)

This harvest mite, or, as it is called in France le rouget, is most troublesome at the end of summer or at the beginning of autumn, when it is found in enormous numbers in grass and amongst many other plants—gooseberries, raspberries, currants, haricot-beans, sorrel, and elderberries. From these plants it passes on to any warm-blooded animals: particularly it attacks small mammals. Hares, rabbits, and moles are often covered with them, but they leave their victim, should it be shot, as soon as the body chills. They are particularly common in Great Britain and in the centre and west of France, and in certain parts of Germany. These irritating little semi-parasites may be dislodged by the application of petrol or benzine—both very inflammable—and the itching they cause allayed by the application of acid or alcoholic lotions.

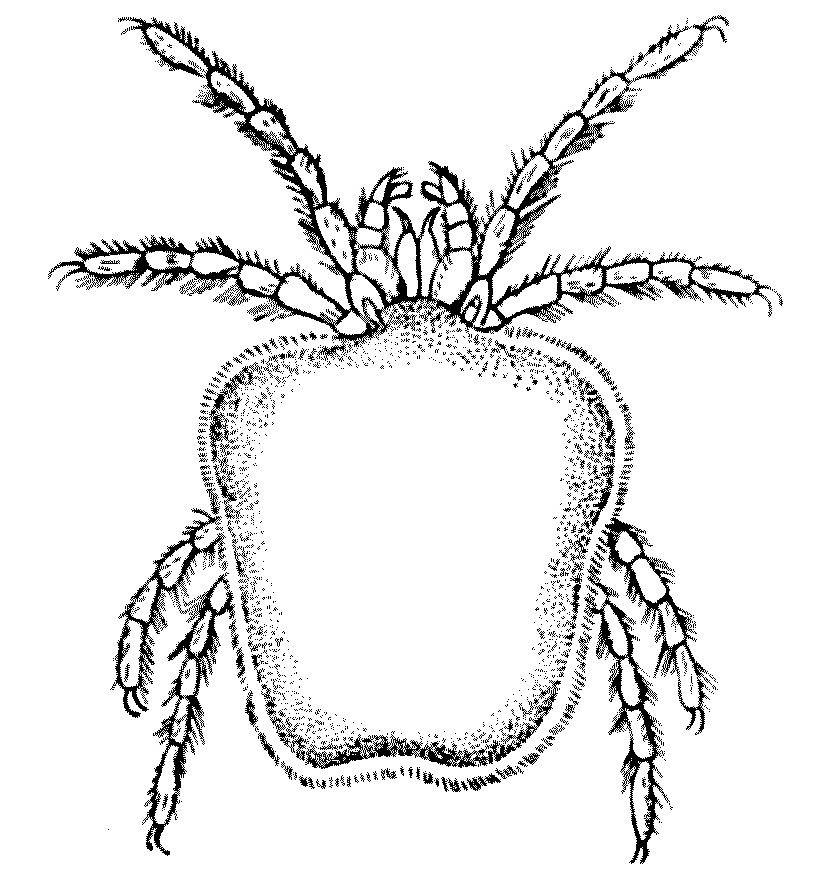

FIG. 32.—Leptus autumnalis (× 100). The so-called proboscis is formed around the hypo-pharynx sunk into the skin. (After Trouessart).

Men working in the fields are frequently attacked. During September 1914, the soldiers of the Sixth Division, stationed in and about Cambridge, and living in tents, suffered severely from their ‘bites.’ They mostly attacked the ankles, the wrists, and the neck, but they rapidly extend over the body. If they be checked by the presence of any stricture, such as a garter or wrist-band, they accumulate behind it, and the irritation is accentuated. The presence of their hypo-pharynx in the skin causes the surrounding tissues to harden and form a cylindrical tube—the so-called proboscis.

The amount of trouble they cause varies very greatly in different people. Children and women with soft skins suffer, as a rule, most; but, as happens in the case of other biting insects, certain individuals seem to be almost immune, whilst others suffer very considerably. The trouble is caused by the mite implanting its mouth-parts in the skin—preferably in the hair-follicles or the sweat-glands. When it is once fixed it rarely moves. The body remains, of course, on the surface of the skin as a little reddish-orange point, scarcely perceptible unless many of them are congregated in the same position. The effect of their presence is to produce a swelling in the skin, which may be as large as a split pea, accompanied by an intense itching and a smarting which banishes sleep. This leads to the patient scratching, and this scratching is the departure-point of many troubles. Scoriated papules appear and eczematous patches, and when the mites are very numerous an erythema, named by Rubies Erythema autumnale, supervenes. The skin near the point of puncture swells, becomes red, sometimes almost purple, and irregular patches, which when confluent, appear a centimetre in diameter.

These skin troubles, which may end in a kind of generalised eruption, are accompanied by a rise of temperature and a certain—sometimes a high—degree of fever. Besides men, dogs and cats suffer from these pests; and in these domestic pets the parasites give rise to a miliary eruption. Domestic cattle—sheep and horses—are also attacked. And, according to some authorities, poultry are not only attacked but killed by these parasites. The larvae apparently only lives a few days in the skin of the victim.

As far as is known at present the larvae of Trombidium convey no protozoal disease; but there is a terrifying little creature, known as the Kedana mite, which in some districts of Japan causes a serious illness, with a mortality of some 70 per cent. Apparently, it does not act as an inoculating agent itself, but the papule, surrounded by the red area which forms as a result of its bite, changes to a pustule, and this lesion becomes the point of entrance of bacteria which produce the so-called ‘river’ or ‘flood’ fever. If these mites be carefully removed the patient suffers no harm.

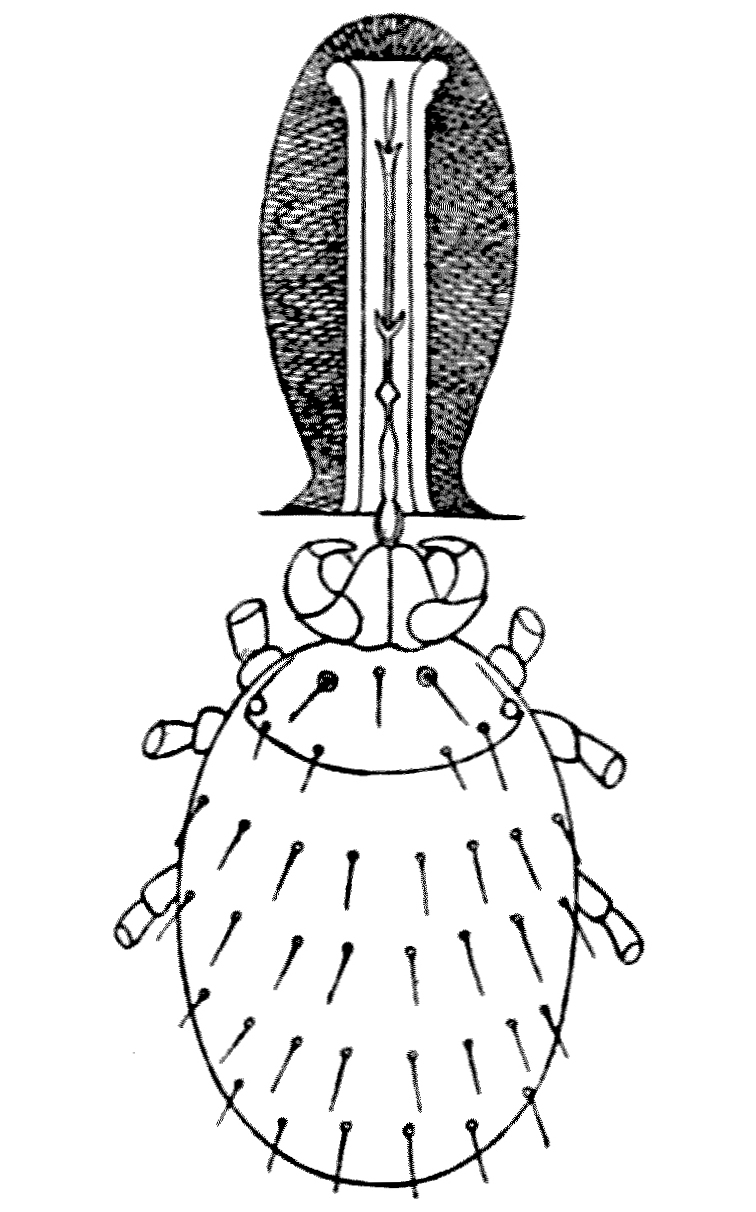

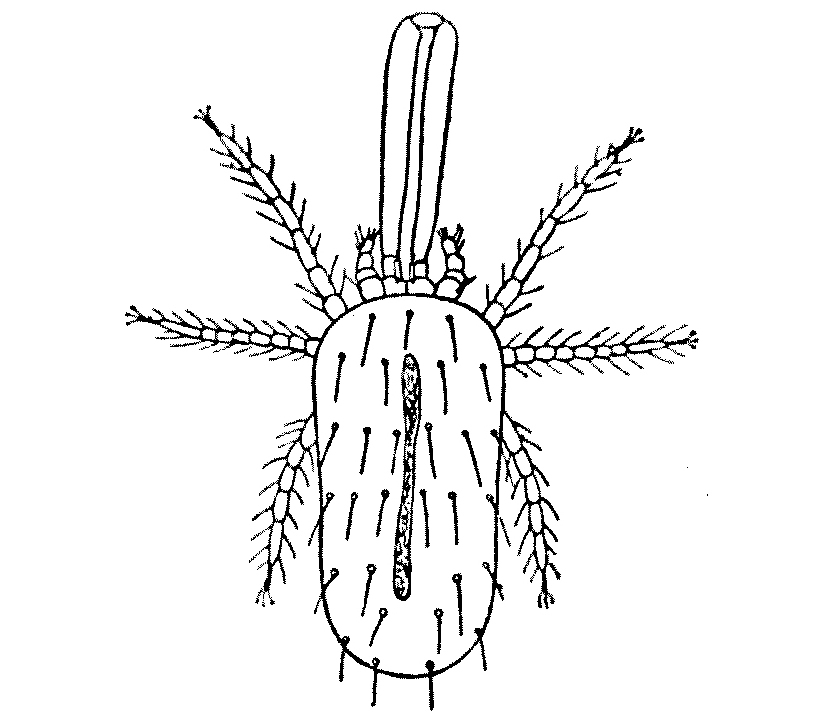

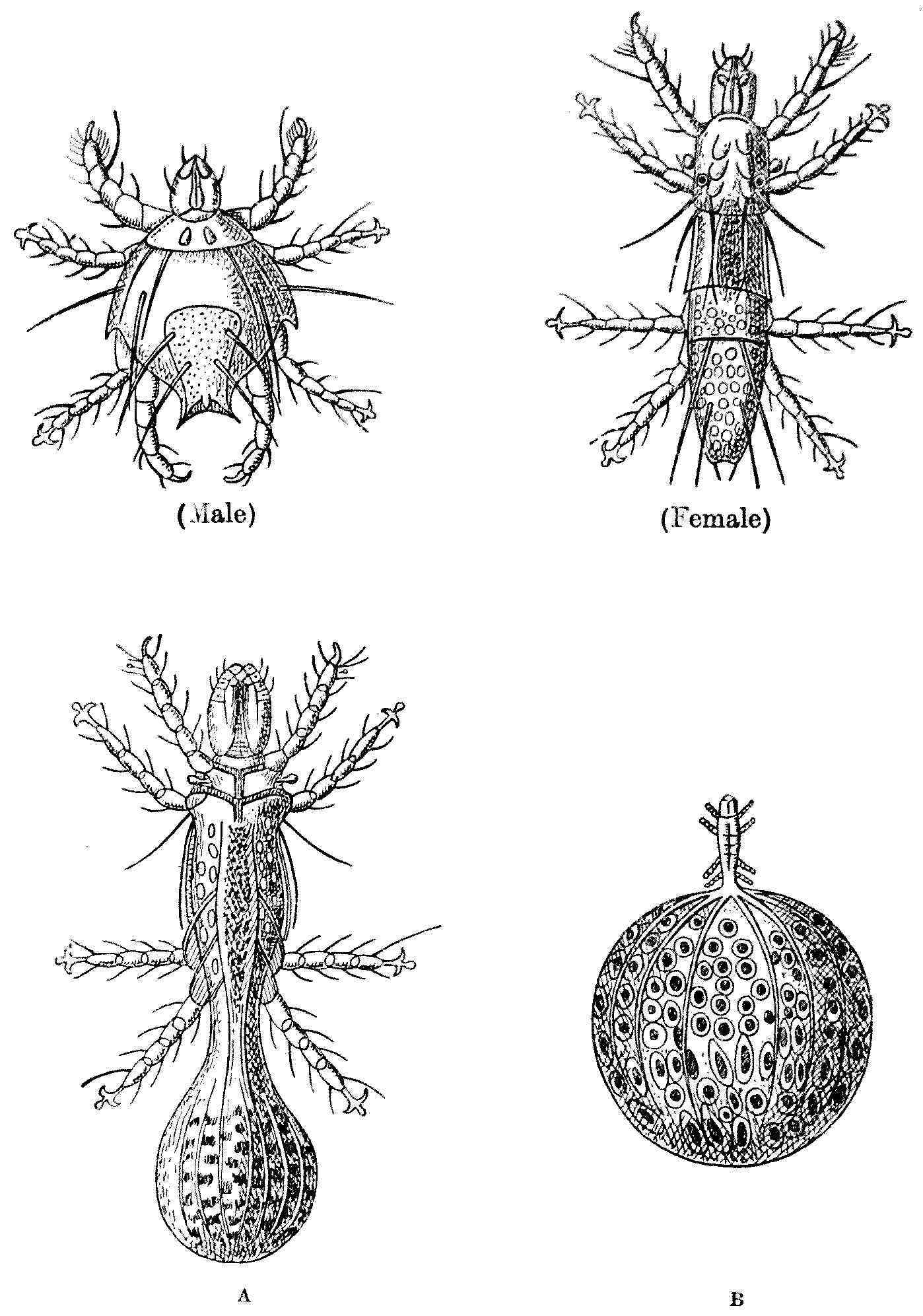

Another species of mite, Pediculoides ventricosus, lives in stalks of cereals, and is very apt to attack labourers who are dealing with grain. Their bites cause severe irritation, local swellings, reddening of the epidermis, and fever. In this particular species the female before she is fertilised has an elongated form 0·2 mm. in length and 0·07 mm. in breadth; but when fertilised the ovaries increase to such an extent that the posterior end of the body becomes spherical. In this respect it resembles that remarkable flea, the chigo or jigger. The larvae are exceptional in being born with four legs instead of the usual three, and they pair almost immediately after emerging from the egg-shell.

FIG. 33.—Pediculoides ventricosus. Male, ventral view (× 250). Female, before fertilisation (× 225). A, after fertilisation; the abdomen has begun to swell (× 250). B, with abdomen fully swollen (× 40). (After Laboulbène and Mégnin.)