CHAPTER VIII

MITES

PART II

ENDO-PARASITIC MITES (Demodex, Sarcoptes)

Say what the use, were finer optics giv’n,

T’ inspect a mite, not comprehend the heav’n.

(POPE, Essay on Man.)

DEMODEX

WE have seen that harvest mites are wont to insert their heads—or rather their mouth-parts—into the skin of human beings, but other mites show less restraint, and insert their whole bodies. One of these, the well-known Demodex folliculorum, is, according to Guiart and Grimbert, ‘Le plus commun des parasites de l’homme et nous en sommes presque tous porteurs.’ Without taking quite so gloomy a view, Demodex is undoubtedly widely distributed in the skin of mankind and of other mammals.

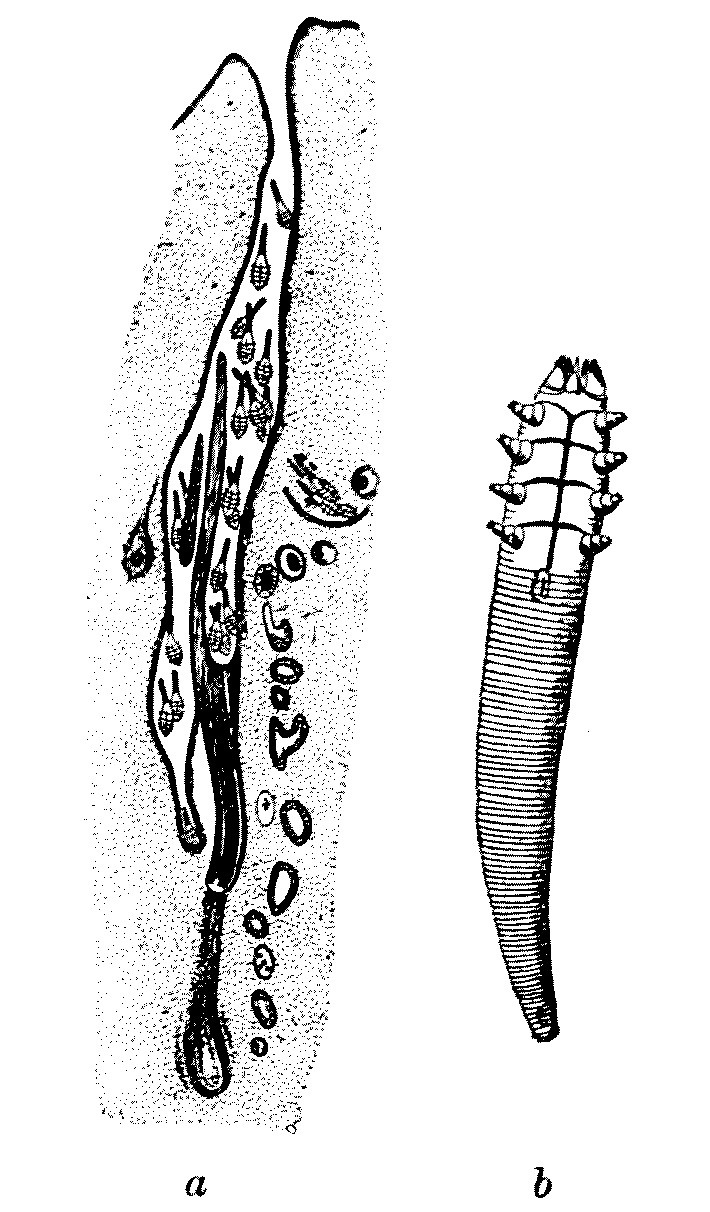

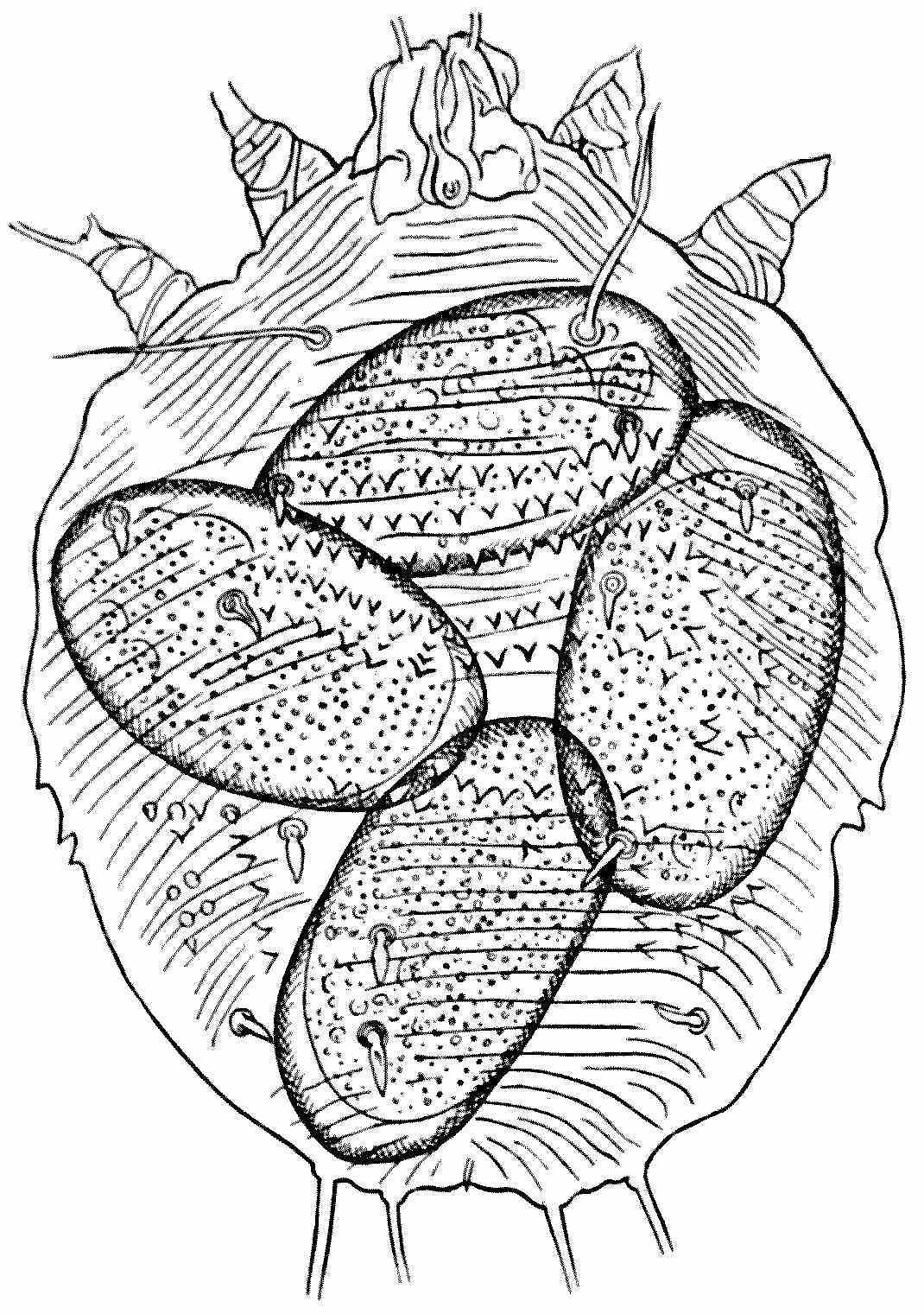

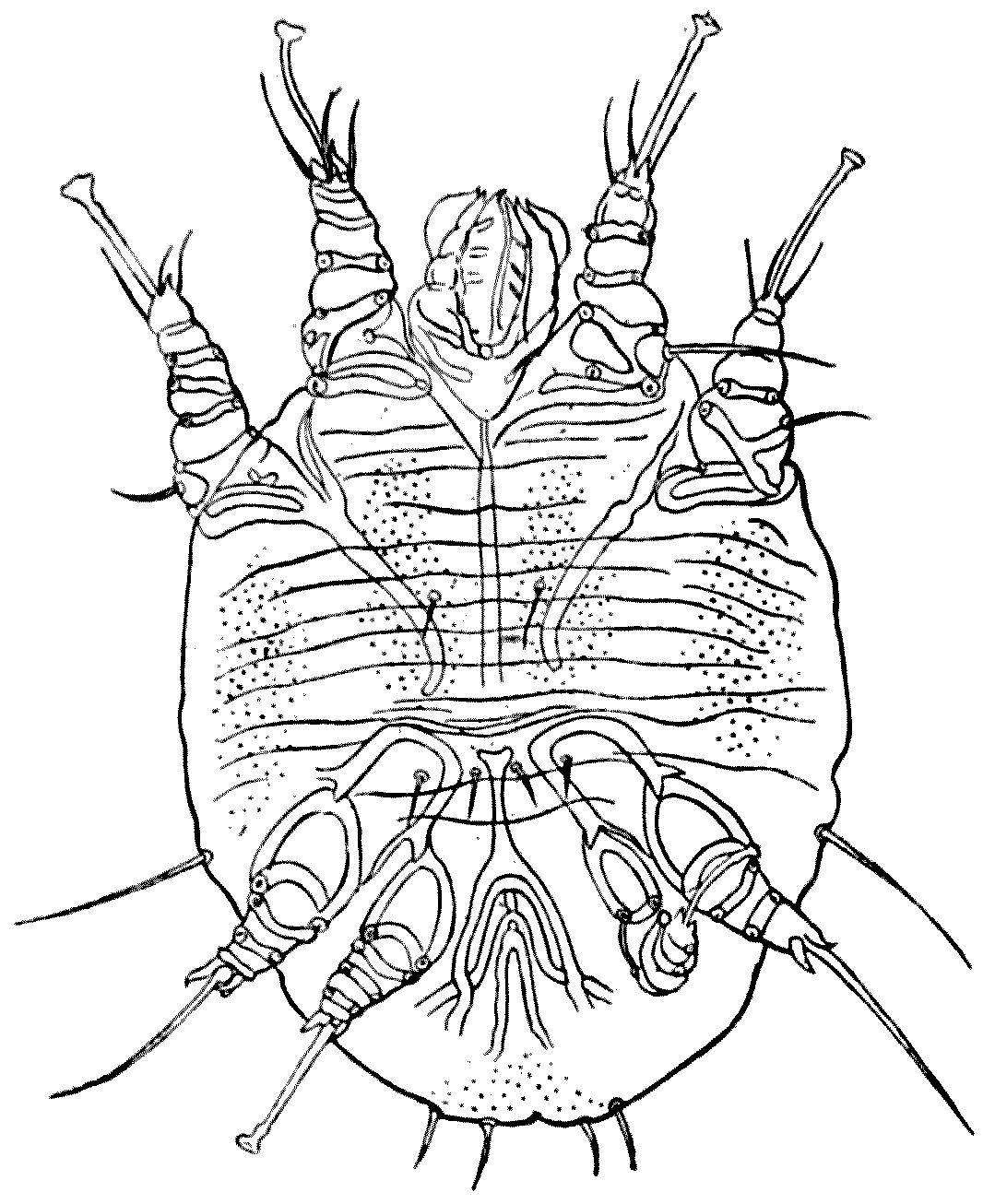

FIG. 34.—(a) Demodex in hair-follicle of dog; magnified. (After Neumaun.) (b) Demodex folliculorum; highly magnified. (After Railliet.)

There are differences of opinion as to whether this form should be split up into numerous species, or subspecies, according to the genus of the mammals upon which it lives. We, at any rate, will confine our attention to the human kind and so avoid losing ourselves in the tortuous maze of synonymy and the arid discussion of a meticulous classification so dear to the analytical German mind. To us a Demodex shall be a Demodex, and we will leave it at that.

Unlike the majority of mites, Demodex is a good deal longer than it is broad. But even for a mite it is very small, and shows signs of bodily degradation associated with its parasitic habit of life. Its shape is adapted to its habitat, which is the sebaceous glands of the skin. The long abdomen appears to be segmented, but the annulations are not true segments. The legs are reduced to conical stumps. The male is 300 µ[12] long and 40 µ broad across the cephalothorax. The female is, as usual, larger, measuring 380 µ in length by 45 µ in breadth. The minute larvae have, as is so often the case with mites, but three pairs of legs, and are 60 µ to 100 µ in length.

This parasite, which lives on all parts of the skin of the human body, is perhaps most commonly seen on the nose and in the passages leading into the ear. It can be expressed by firmly pressing over the black spot which indicates its presence in the skin of the nose or elsewhere any small cylindrical tube, such as a watch-key. When expressed it is not always easy to see, as coming away with it is a mass of sebaceous matter which can best be dissolved off with oil on the microscopic slide. Whether this particular parasite causes much disease is not known. But in some cases it is certainly associated with acne and other skin disorders; and as it is also found in hair-follicles, it may possibly destroy the hair. It is apparently spread by personal contact.

THE ITCH-MITE

A much more serious trouble is due to Sarcoptes scabiei—often called the Acarus—which gives rise to the disease known in England as the ‘itch’ and in France as the ‘gale.’

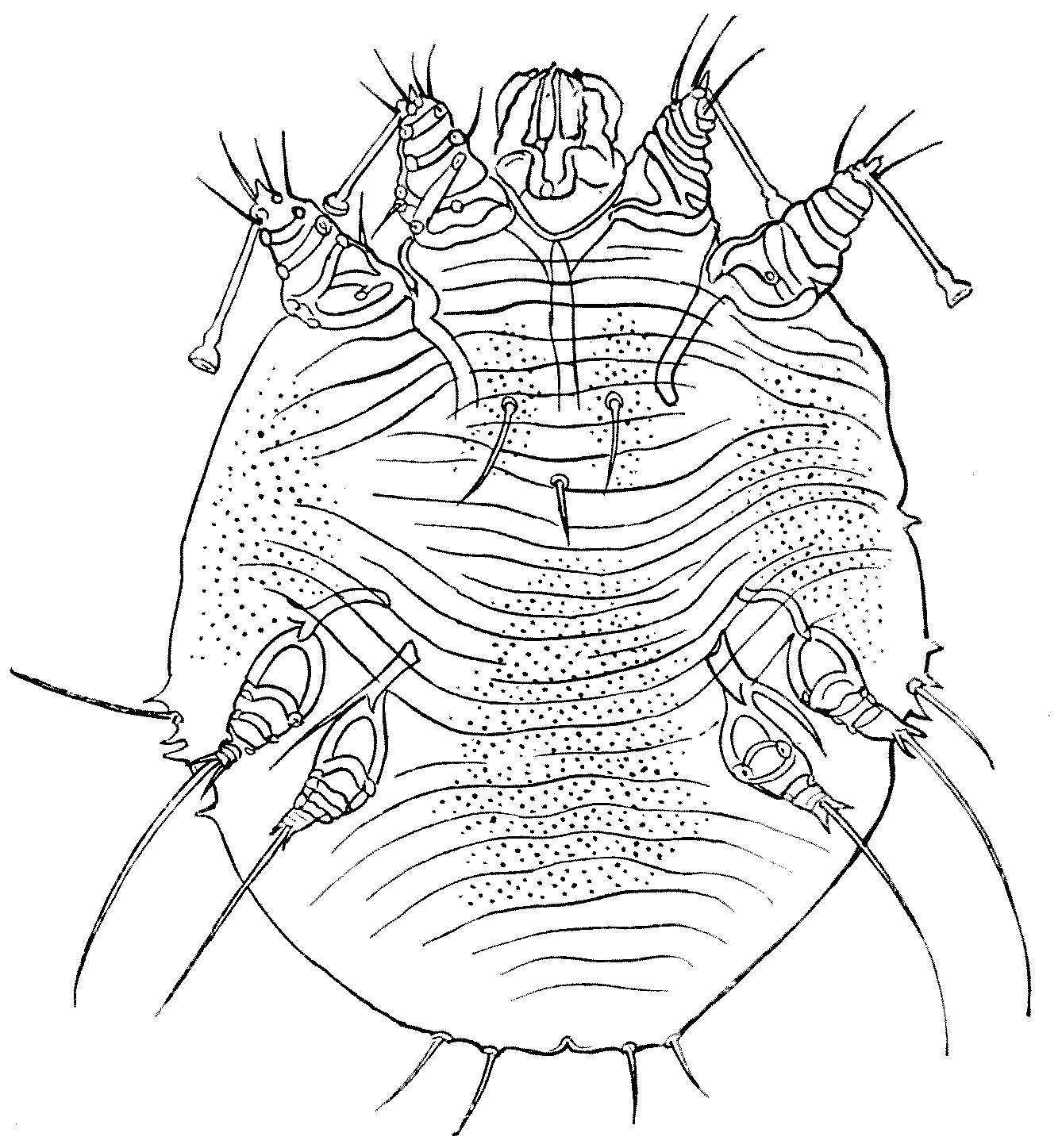

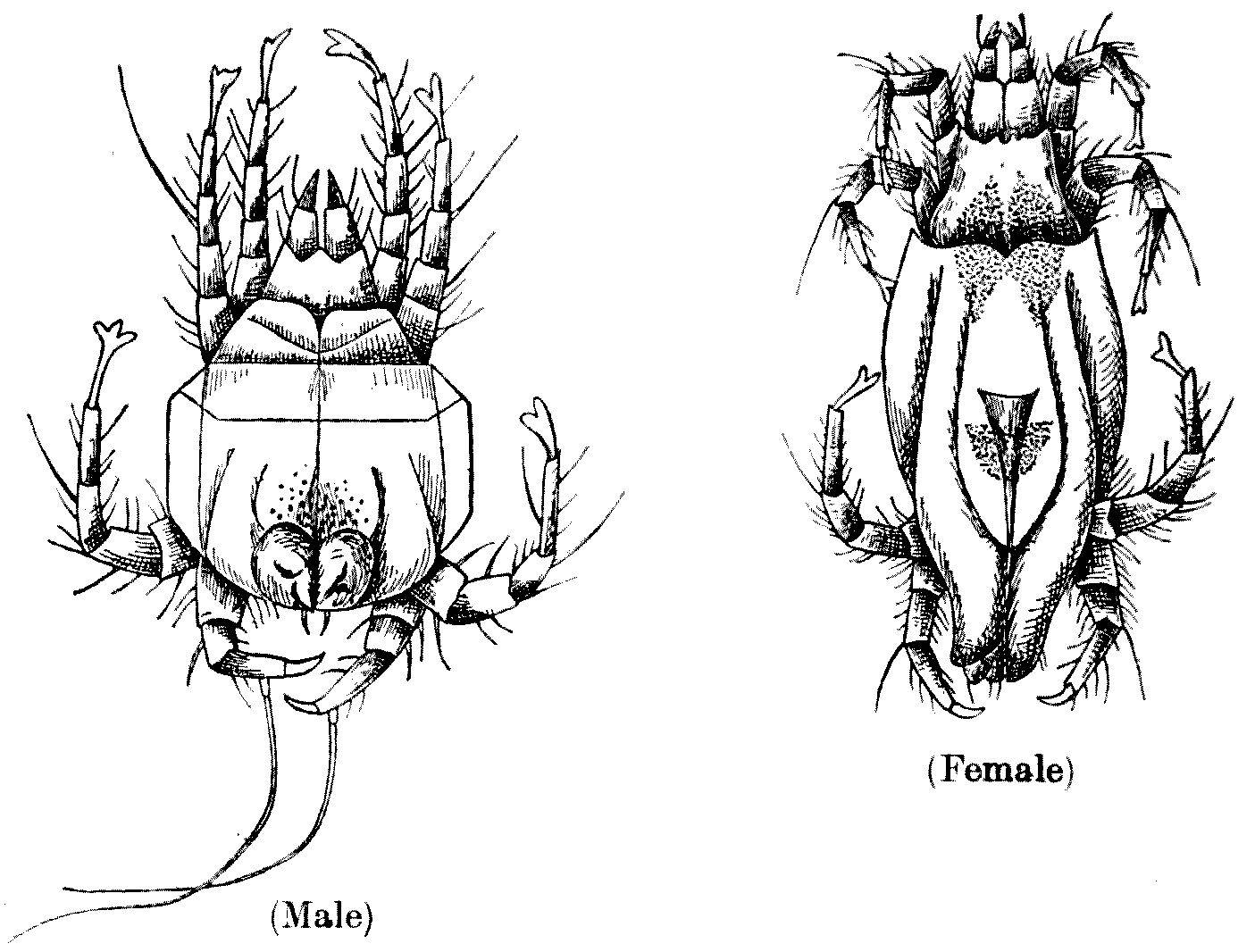

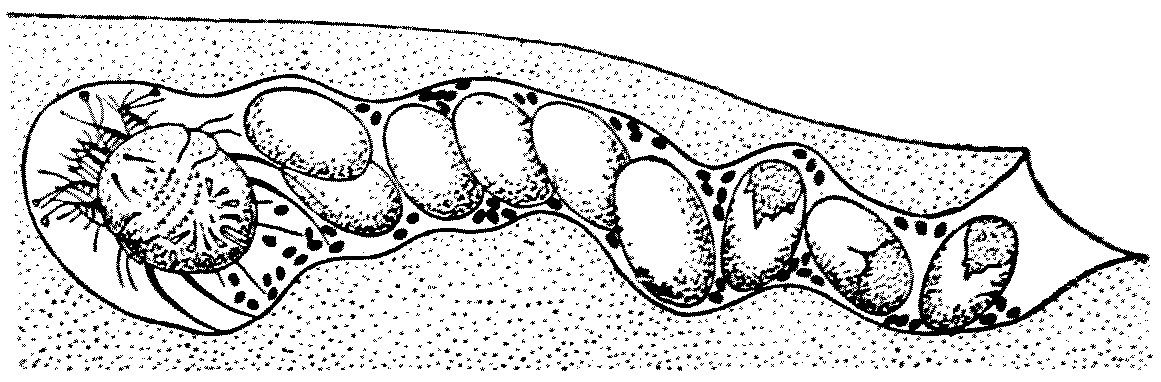

FIG. 35.—Sarcoptes scabiei. Female. × 180. Ventral view.

(From Bourguignon.)

Sarcoptes scabiei in both sexes is but little longer than broad. The female is, as usual, larger than the male. These mites are shaped very much like microscopic tortoises, of a pearly grey colour, passing at parts into a rusty brown. Of the four pairs of legs two run forward close to the head, and two point backwards. The integument is semi-transparent and strengthened by parallel folds, and bears many little bilaterally symmetrical protuberances and scales. There are also certain hairs which have some systematic value.

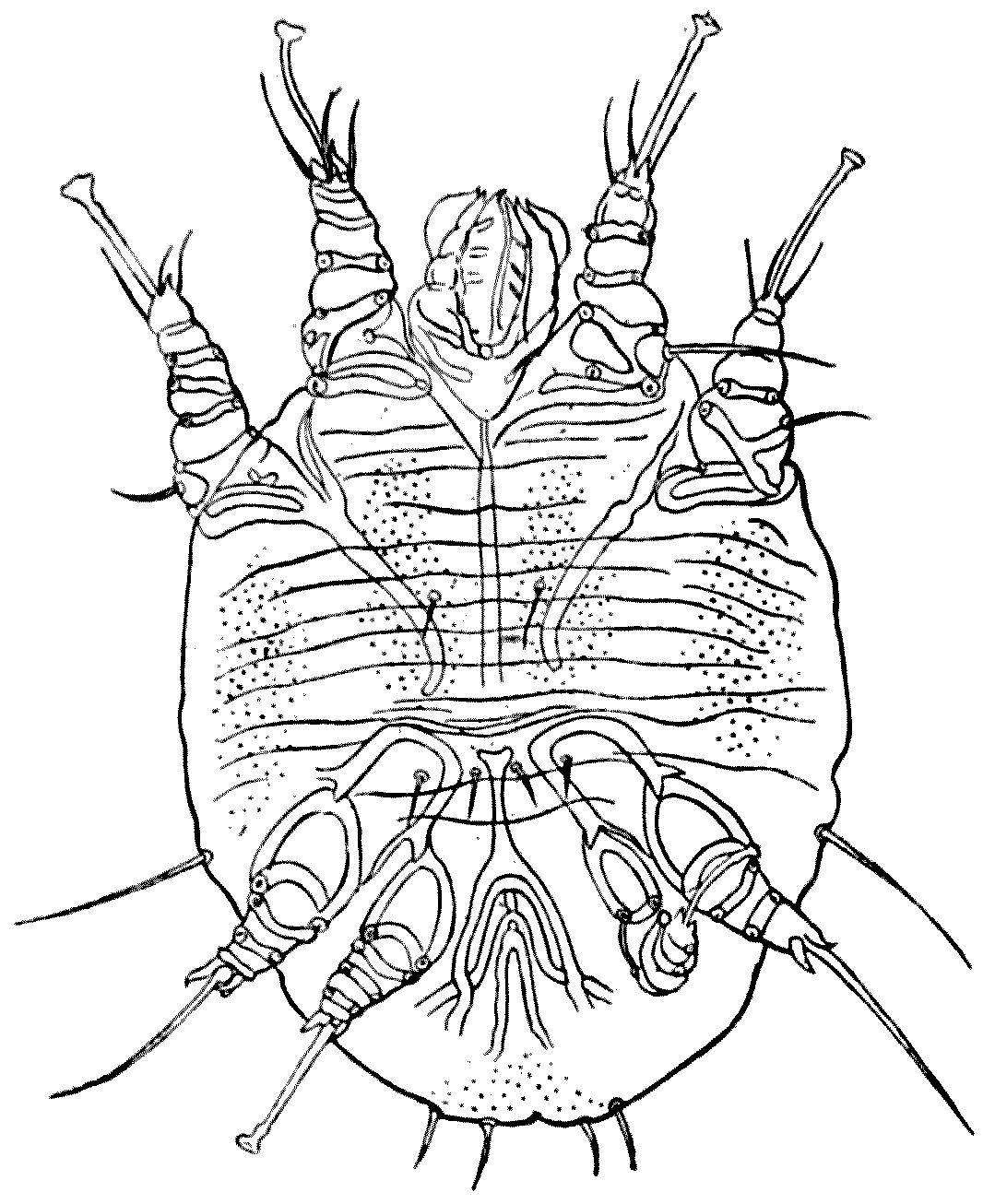

FIG. 36.—Sarcoptes scabiei. Male. × 300. Ventral view. The sucker on the fourth leg on the right is accidentally folded over the third leg. (From Bourguignon.)

The male is usually recognised by the fact that its third pair of legs terminates in a long hair, whilst the other legs end in pedunculated suckers.

FIG. 37.—One of the legs of Sarcoptes scabiei (× about 450), showing the stalked sucker and the curious ‘cross-gartering.’ (After Bourguignon.)

The male measures 200 µ to 235 µ in length, by 145 µ to 190 µ in breadth. By preference, he lives under the scales which the presence of the parasite produce on the human host. The female is markedly larger than the male, measuring 330 µ to 450 µ in length by 250 µ to 350 µ in breadth. Her two anterior legs end in stalked suckers, whilst the two posterior end in hairs. The legs, like Malvolio’s, are curiously ‘cross-gartered’ with chitinous bars and rings.

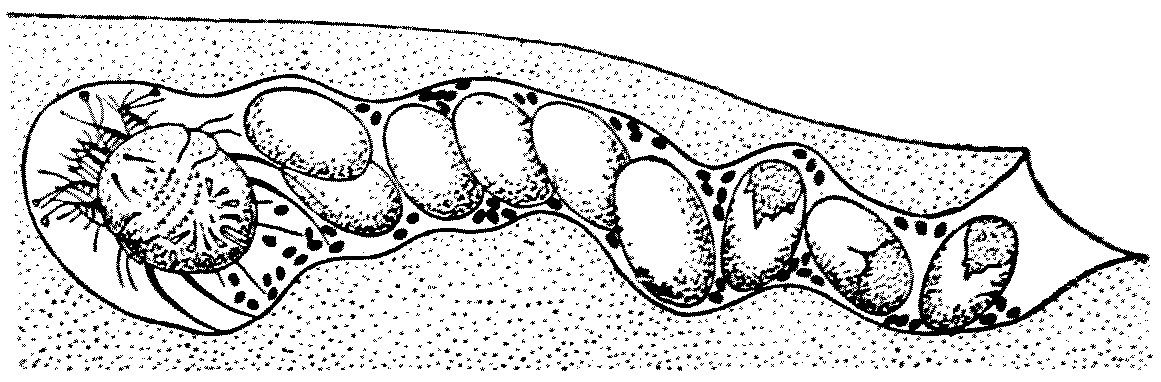

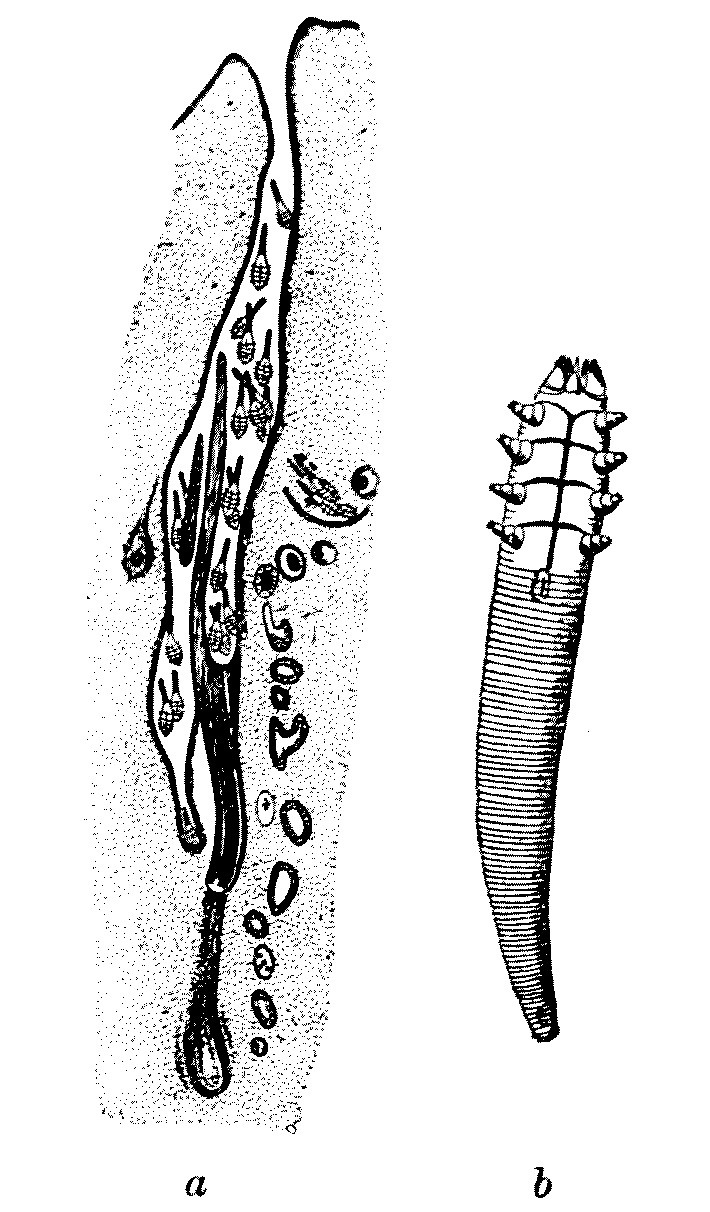

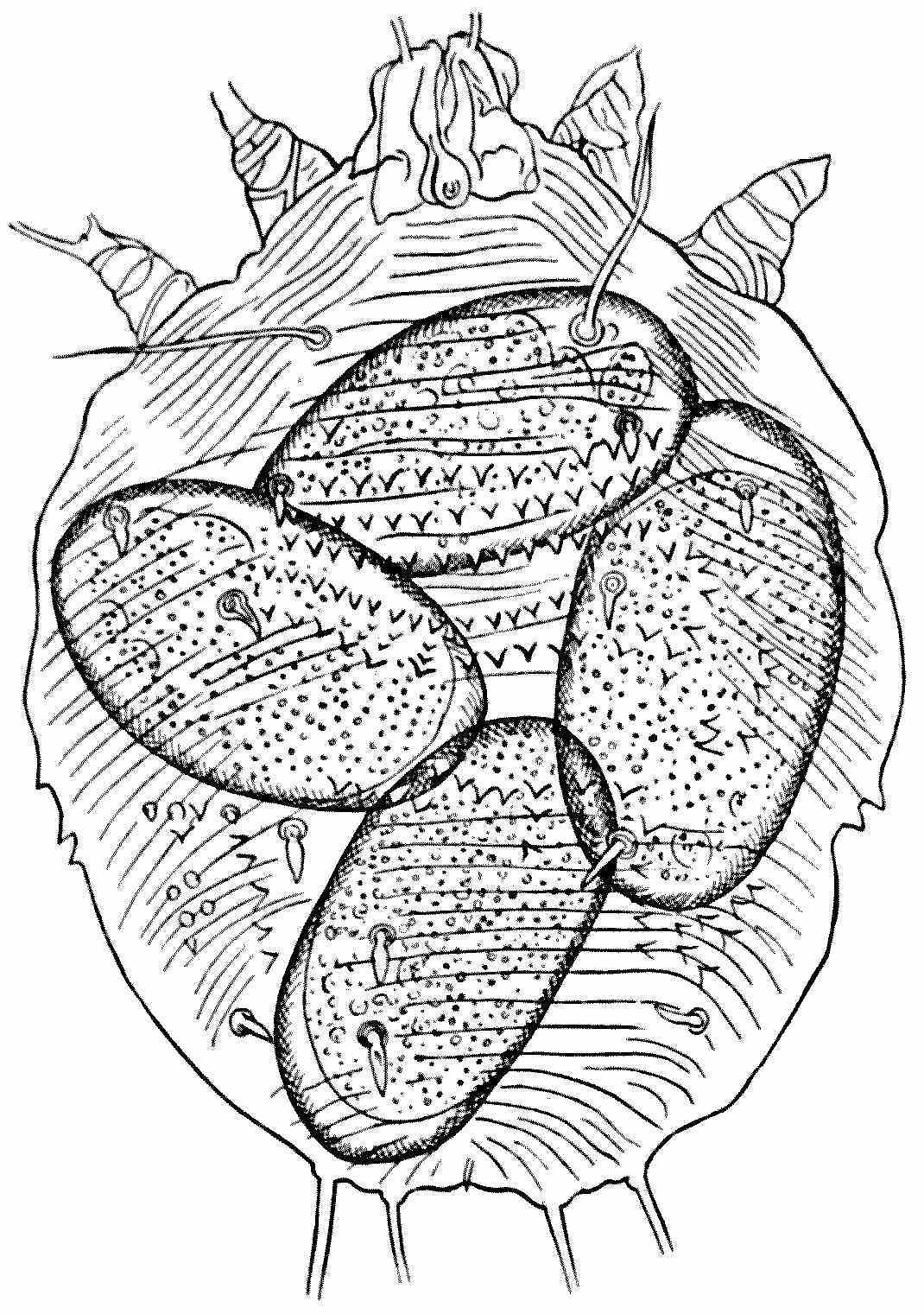

At first she promenades about with the male on the surface of the human skin, but when they have paired the female begins to tunnel in the epidermis. The poor male, having been used, dies. As the mother-mite tunnels she begins to lay eggs, leaving them one by one behind her as she burrows deeper and deeper into the epidermis. Hence those that are nearer the entrance of the tunnel are always more advanced in age and development than those farther in. She always works head forward, and as her tunnel is but slightly bigger than the breadth of her body, she cannot turn round, and she is prevented from retreating by the backward hairs or spines of her body. Hence she burrows always forward, until she has dug her own grave at the far end of her excavation.

She is said to live two or three months and to lay one or two eggs a day. Thus one female is, in time, enough to infect seriously a single host. The egg is, relatively to the size of the mother, enormous: its length being 150 µ and its width 100 µ. The egg is hatched out after three to six days, and the young larva is hexapodous—that is, as is so usual in Acarines, six-legged. It escapes from the burrow on to the skin and soon tunnels into the epidermis of its host, where it moults and transforms, about the ninth day, into a four-legged nymph. At the end of another six days the mites moult again, and at this period one can distinguish nymphs of two sizes: the larger female, and the smaller male.

FIG. 38.—A diagrammatic view of the tunnel made by the female of Sarcoptes scabiei, with the eggs she has laid behind her as she burrows deeper and deeper. The black dots represent the excrement. (After Guiart and Grimbert.)

Within a month after hatching the Sarcoptes has become adult, and the sexes are occupied in seeking each other on the surface of the skin, and it is in this stage that they are easily passed by personal contact from one human being to another.

FIG. 39.—A female Sarcoptes scabiei, with four eggs in different stages of development; × about 180. (After Bourguignon.)

Many animals suffer from Sarcoptes; and the fact that this genus can be transferred to man from the horse, the ox, the sheep, the goat, the dog, the cat, the camel, the lion, &c., is a slight argument in favour of their being one species. There is another undoubtedly distinct species which causes serious epidemics, especially in Norway; but that is hardly likely to enter into the scope of this book.

Sarcoptes scabiei, the itch-mite, is, however, a cause of serious trouble in an army ‘in being.’ The tunnel or gallery in which the female mite burrows is the only lesion produced directly by the parasite. To the naked eye it presents a little whitish or greyish line, varying in length from some millimetres to one or even three centimetres, the longer ones occurring most frequently on the hands or wrists. It is of course open at one end, and ends in a cul-de-sac, which is slightly swollen, and here it is the female has taken up her abode. She is visible as a small white, brilliant spot. Besides the wrist, and the inner faces of the fingers—the interdigital areas—the palms of the hands are most commonly affected.

If there is any doubt as to the cause of the existence of these tunnels, a diagnosis can easily be verified by extracting the mite. With the point of a needle, held almost parallel to the skin, the tunnel can be slit open, and when the point has reached the inner end the mite is very apt to seize it with its suckers, and can be so withdrawn, and, if not, it can easily be picked out. It can then be examined in a drop of diluted glycerine under a microscope.

I am no doctor, hence I venture to refer my readers to the article on Scabies in the ‘Encyclopaedia Medica,’ by Dr. G. Pernet, and to quote the following paragraphs from Dr. H. Radcliffe Crocker’s ‘Diseases of the Skin,’ third edition, vol. ii.:—

Symptoms of Pathology.—The clinical picture of scabies is made up of two elements: the burrows, or cuniculi, and the attendant inflammation excited directly by the Acarus scabiei[13]; and, indirectly, the lesions produced by scratching, and the modifying influences of pressure, friction, &c. The result is a great multiformity of lesions, which, combined with their distribution, is in itself suggestive of the nature of the disease, and enables a practised eye to detect a well-marked case at a glance.

When the skin is first penetrated by the acarus, inflammation is often set up, and a papule, vesicle, or pustule is the consequence. These papules or small vesicles, individually indistinguishable from eczema vesicles, are the most common form of eruption; but the inflammatory symptoms are absent in many burrows. The tract extends and forms a sinuous, irregular, or rarely straight line, which in very clean people is white, but, as a rule, is brownish or blackish from dirt being entangled in the slightly roughened epidermis; the length of these burrows is generally from an eighth to half an inch, but occasionally much longer—Hebra having noticed one four inches long. When a pustule is formed, part of the burrow lies in the roof, but the acarus is always well beyond the pustule or vesicle; or, if there is none, lies at the far end, and with a lens may often be discerned as a white speck in the epidermis. The degree and number of inflammatory lesions vary much; there may be no inflammation at all about many burrows, or the whole hand—especially in children—may be covered by pustules, vesicles, or papules; and, indeed, a pustular eruption on the hands is always strongly suggestive of scabies; there is, however, no grouping or arrangement of any of the eruptions, as in eczema, the lesions being scattered about irregularly. It must be remembered that burrows are not always present, from various causes. If the disease is recent it may not have got beyond the papular or vesicular stage; while in washerwomen, bricklayers, or others whose hands are constantly soaked in water or alkaline fluids, or who have to scrub their hands violently, the burrows become destroyed. The eruptions due to scratching have already been described in the descriptions of the ‘scratched skin,’ and comprise excoriations, erythema in parallel lines, eczema, impetiginous or so-called ecthymatous eruptions and wheals, and the inflammatory scab-topped papules often left after the subsidence of the wheals—especially in children. In carmen, cobblers, tailors, and others who sit on hard boards for hours together, pustular and scabbed eruptions, situated over the ischial tuberosities, are so abundant and constant as to be practically diagnostic of scabies in such people. Similar eruptions may be seen where there is friction from trusses, belts, &c.

Treatment.—I use in private practice, after the preliminary soaking and scrubbing, naphthol 15 parts, cret. prep. 10 parts, sap. mollis 50 parts, adipis 100 parts, as recommended by Kaposi, well rubbed in. For infants it can be used half-strength, and I omit the soft-soap. I can speak of it in the highest praise. It is effectual, has no smell, and is not liable to irritate the skin, as sulphur does. It is, however, too expensive for public practice. Nephritis has occurred from its over-use, but I have never seen any bad symptoms. Another remedy less likely to irritate the skin than sulphur is balsam of Peru, of which the vapour alone is said to be fatal to the acari. The balsam is rubbed in for twenty minutes every night; a night-shirt impregnated with the drug is worn, and in the morning an ordinary soap-and-water bath is taken.

Colonel Allcock says that the best treatment for the itch ‘consists in the free use of soap and hot water and the liberal application of sulphur ointment, continued for several days. Some prefer baths of potassa sulphurata (1 ounce of the salt to 4 gallons of water). Clothing and bedding should be fumigated with sulphur or baked.’

ENDO-PARASITIC MITES

Certain little mites whose appearance is as repellent as their name—for they are known as Nephrophages sanguinarius—were recorded by two Japanese observers twenty years ago as coming away in the urine of a Japanese patient who was suffering from various bladder troubles. As the mites were in all cases dead, the Japanese doctors thought that they must have been endo-parasites of the kidney. They were found day after day for a week or more, and they were found also in the water with which the bladder had been washed out, but always dead. It is, of course, possible that the Japanese doctors were right in their surmise, but the best that can be said for the case is that it is ‘not proven.’

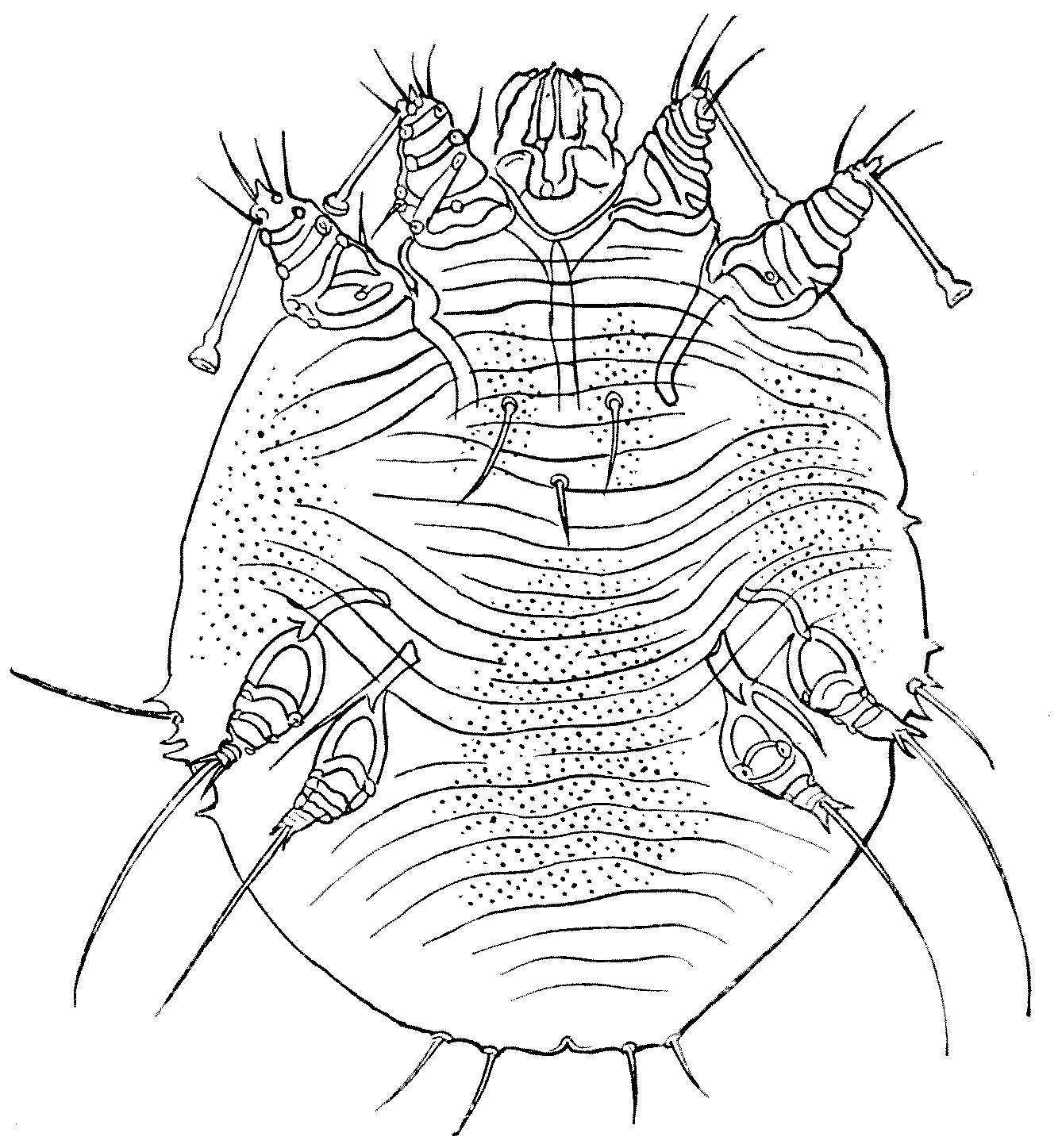

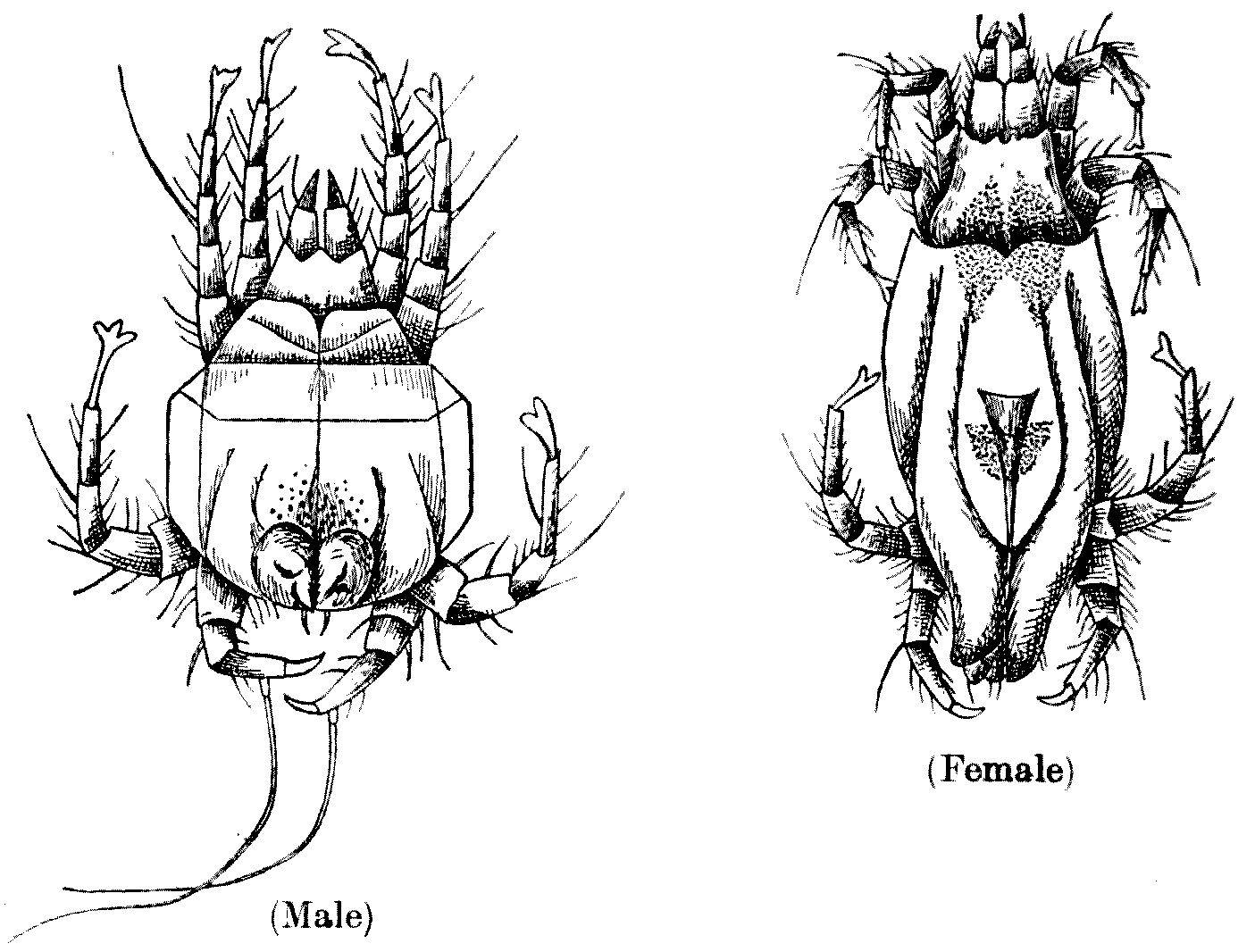

FIG. 40.—Nephrophages sanguinarius (enlarged). Male, ventral surface. Female, dorsal aspect. (After Miyake and Seriba.)

These awful-looking little mites are said to have two large eyes, and legs of five segments and of equal length. Their colour is greenish to brownish yellow. Undoubtedly there are many mites which live as endo-parasites; certain members of the group Analgesinae, such as Laminosioptes gallinarum, live in the intramuscular and subcutaneous tissue of fowls, and Cytoleichus sarcoptioides in their air-sacs. I have myself found one of these species in the pigeon, so that it is by no means beyond the bounds of human possibility that Nephrophages sanguinarius really lived in the tissues of the Japanese. Very strange things live in the tissues of some Japanese.