CHAPTER XII

LEECHES

PART III

EXOTIC LEECHES

(Limnatis nilotica and Haemadipsa zeylanica).

Rulers that neither see nor feel nor know,

But leech-like to their fainting country cling,

Till they drop, blind in blood, without a blow.

(SHELLEY, England in 1819.)

THE extension of war into the Near and Far East has brought into action two genera of leeches which were and still are the cause of extreme inconvenience and even of real danger to troops operating in these areas. The enemies of our Allies will still insist on fighting on richly stocked leech-grounds. For in the new war area, in southern Europe, Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and parts of India and the real East, two genera of leeches—which are indeed not the friend but the enemy of man, especially of the soldier—abound.

The first of these two is Limnatis nilotica (Sav.), and it is from Savigny that I have stolen the picture of this species.

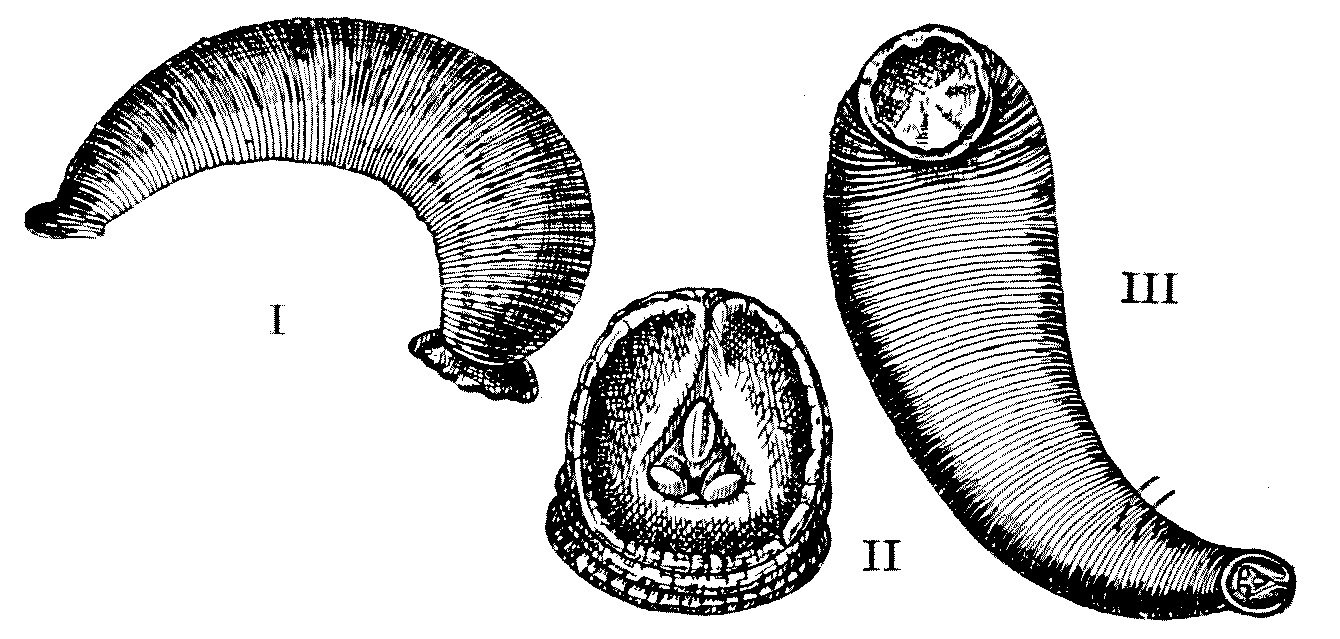

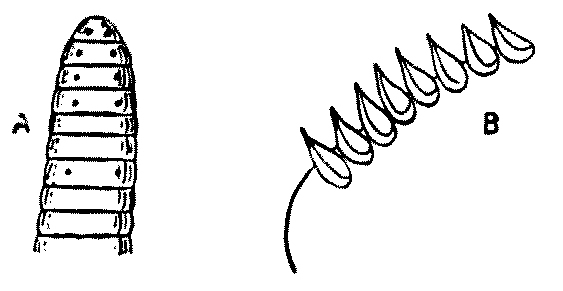

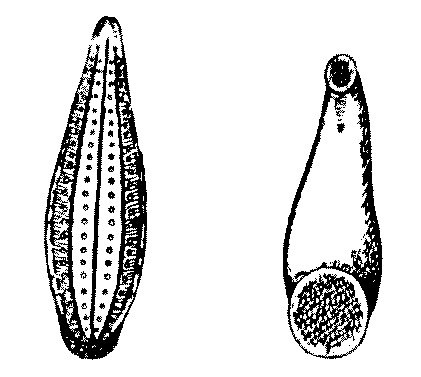

FIG. 58.—I. Limnatis nilotica, side view. II. Oral sucker, showing the characteristic median dorsal slit and the three teeth; III. ventral view. (From Savigny.)

It is a leech of considerable size, attaining a length of 8 cm. to 10 cm., and its outline rather slopes inward at the anterior end. The dorsal surface is brownish-green with six longitudinal stripes, and the ventral surface is dark. It is a fresh-water leech, and it occurs from the Atlantic Islands, the Azores, and the Canaries—its western limit—all along the northern edge of Africa until it reaches Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Armenia, and Turkestan, where it achieves its uttermost eastern boundary. This leech lives in stagnant water; especially does it congregate in drinking-wells—the wells so often mentioned in the New Testament. In the Talmud (Abōdāh Zārāh, 17b) an especial warning is given against drinking water from the rivers or wells or pools for fear of swallowing leeches. Doubtless the New Testament Jew knew in his day almost as much as we know now about these leeches. They were the cause of endless trouble to Napoleon’s soldiers in his Egyptian campaign, and are still a real pest in the Near East.

I cannot recall that Napoleon talked much about spreading ‘Kultur,’[18] but he certainly did it. He took with his army into Egypt a score of the ablest men of science he could gather together in France. He established in Cairo an ‘Institut’ modelled on that of Paris; and his scientific ‘corps’ produced a series of monographs on Egyptian antiquities and on the natural history of Egypt that has not yet been equalled by any other invading force. Napoleon freed the serfs in Germany, he codified the laws of France, and these laws were adopted by large parts of Europe; he extended the use of the decimal system. Napoleon had a constructive policy, and was never a consistent apostle of wanton destruction. If he destroyed it was to build up again, and in many instances he ‘builded better than he knew.’ He seldom so mistook his enemies as to destroy, to terrify; the ‘frightfulness,’ though bad enough in his times, had limits. Napoleon had at least in him the elements of a sane and common-sense psychology. He knew that what was ‘frightful’ to the French was not necessarily ‘frightful’ to the Russian.

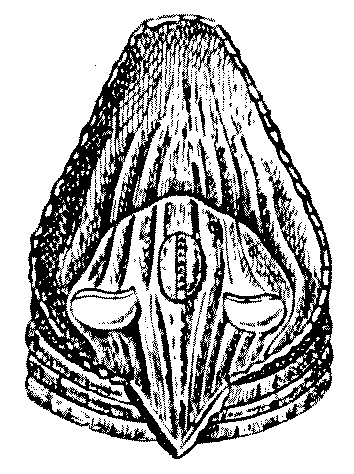

FIG. 59.—Anterior sucker of Hirudo medicinalis. This is to compare with the anterior sucker of Limnatis nilotica, which has a characteristic dorsal median slit. See preceding figure. (From Savigny.)

Amongst the wonderful series of books and monographs on Egypt which described the varying activities of the savants he took in his train, and who, at the confines of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries invaded the country of the Pharaohs, none is more remarkable than Savigny’s monograph on the ‘Natural History’ of that country. And in this folio the leech (Limnatis nilotica) was for the first time fully described and depicted.

This particular leech is swallowed by man, by domestic cattle, and doubtlessly by wild animals, with their drinking-water. Amongst the medical writers of the Eastern world in classical times who mention leeches there was always, as there was amongst the authors of the Talmud, a great and haunting fear of leeches being swallowed, and these writers mostly wrote from the area where Limnatis nilotica still abounds.

According to Masterman, who has had, as a medical officer in Palestine, a first-hand opportunity of studying this leech, the pest attaches itself to the mouth or throat or larynx during the process of swallowing, and he is convinced that if it be once really swallowed and reaches the stomach it is killed and digested.

Limnatis nilotica, unlike Hirudo medicinalis the medicinal leech, is unable to bite through the outer integument of man and is only able to feed when it has access to the softer mucous membrane of the mouth or of the pharynx or of the larynx, and of the other thinner and more vascular internal mucous linings.

In Palestine these pests are particularly common in the region of Galilee and in the district of Lebanon. They are, in these and other districts, so plentiful in the autumn that almost every mule and almost every horse the tourist comes across is bleeding from its mouth or from its nose, for this species of leech is by no means only a human parasite. The natives, who know quite a lot about these pests, generally strain them out of their drinking-water by running the water through a piece of muslin or some such sieve when they fill their pitchers at the common well. In certain districts these leeches in the local pools or reservoirs are kept in check by a fish—a species of carp (Capöeta fratercula).

In the cases which recently came under Mr. Masterman’s observation, the leeches were attached to the epiglottis, the nasal cavities, and perhaps most commonly of all to the larynx of their host. When they have been attached to the anterior part of the mouth, or any other easily accessible position, their host or their host’s friends naturally remove them, and such cases do not come to the hospital for treatment.

The effect of the presence of this leech (L. nilotica) on the human being is to produce constant small haemorrhages from the mouth or nose. This haemorrhage, when the leech is ensconced far within the buccal, the nasal, or the pharyngeal passages of the host, may be prolonged, serious, and even fatal. Masterman records two cases under his own observation which ended in death: one of a man and the other of a young girl, both of whom died of anaemia produced by these leeches.

The average patients certainly suffer. They show marked distress, usually accompanied by a complete or partial loss of voice; but all the symptoms disappear, and at once, on the removal of the semi-parasite. Sometimes the leeches are attached so closely to the vocal cords that their bodies flop in and out of the vocal aperture with each act of expiration and inspiration. The hosts of leeches so situated usually suffer from dyspnoea, and at times were hardly able to breathe.

The native treatment is to remove the leech, when accessible, by transfixing it with a sharp thorn; or they dislodge it by touching it with the so-called ‘nicotine’ which accumulates in tobacco-pipes. But nicotine is destroyed at the temperature of a lighted pipe, so whatever the really efficient juice is, it is not nicotine. Still, as long as the fluid proves efficient, the native is hardly likely to worry about its chemical composition.

Masterman says that the two means he has found most effective were: (1) Seizing the leech, when accessible, with suitable forceps; or (2) paralysing the leech with cocaine. In the former case the surgeon is materially assisted by spraying the leech with cocaine, which partially paralyses it and puts it out of action. In the latter case, if the spraying of cocaine is not sufficient, Masterman recommends the application of a small piece of cotton-wool dipped in 30 per cent. cocaine solution, which must be brought into actual contact with the leech’s body. The effect of the cocaine in contact with the skin of the leech is to paralyse it and to cause it at once to relax its hold. In such a case the leech is occasionally swallowed, but it is more often coughed up and out. Headaches and a tendency to vomit are symptoms associated with the presence of this creature in the human body; the removal of the leech or leeches coincides with the cessation of these symptoms.

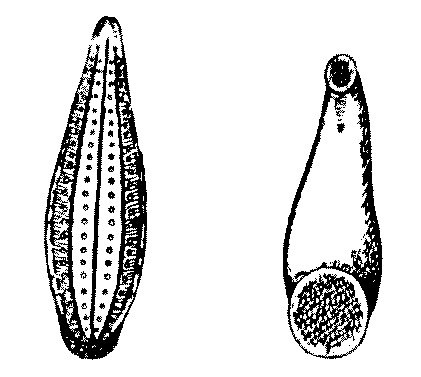

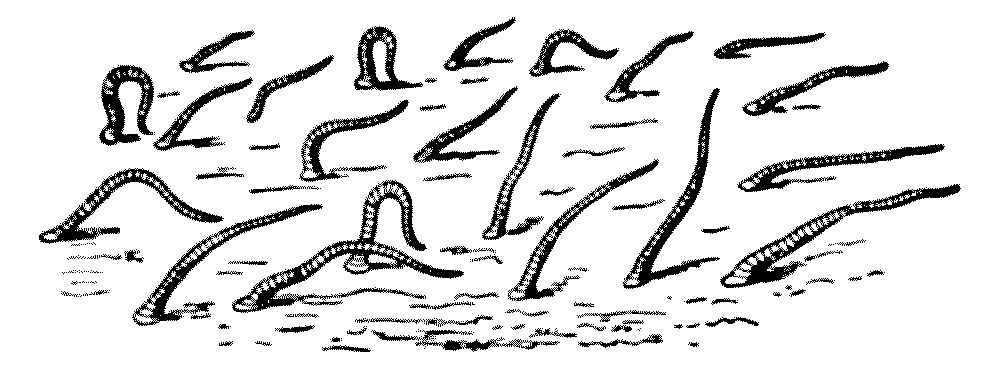

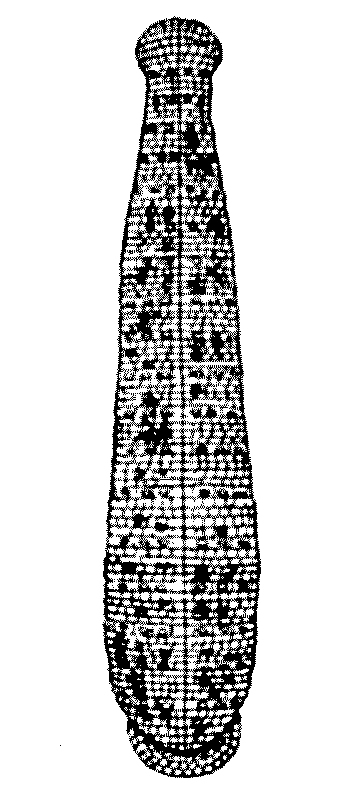

FIG. 60.—The Japanese variety of Haemadipsa zeylanica. × 1. (From Whitman.)

In the East, where many of our Territorial regiments are now stationed, we come across another species of leech even more injurious to mankind than Limnatis nilotica. This Asiatic leech is known as Haemadipsa zeylanica, and is one of a considerable number of leeches which have left the water, their natural habitat, and have taken to live on land.

From India and Ceylon, throughout Burma, Cochin China, Formosa to Japan, the Philippines, and the Sunda Island, this terrible, and at certain elevations ubiquitous, pest is spread. It lives upon damp and moist earth. The family to which it belongs is essentially a family which dwells in the uplands and shuns the hot, low-lying plains. Its members do not occur on the hot, dry, sandy flats. Tennant has described the intolerable nuisance they are in Ceylon. In fact of the many visible plagues of tropical Asia and its eastern islands they are perhaps the worst. Yet few have recorded their dread doings, and those few have escaped credence.

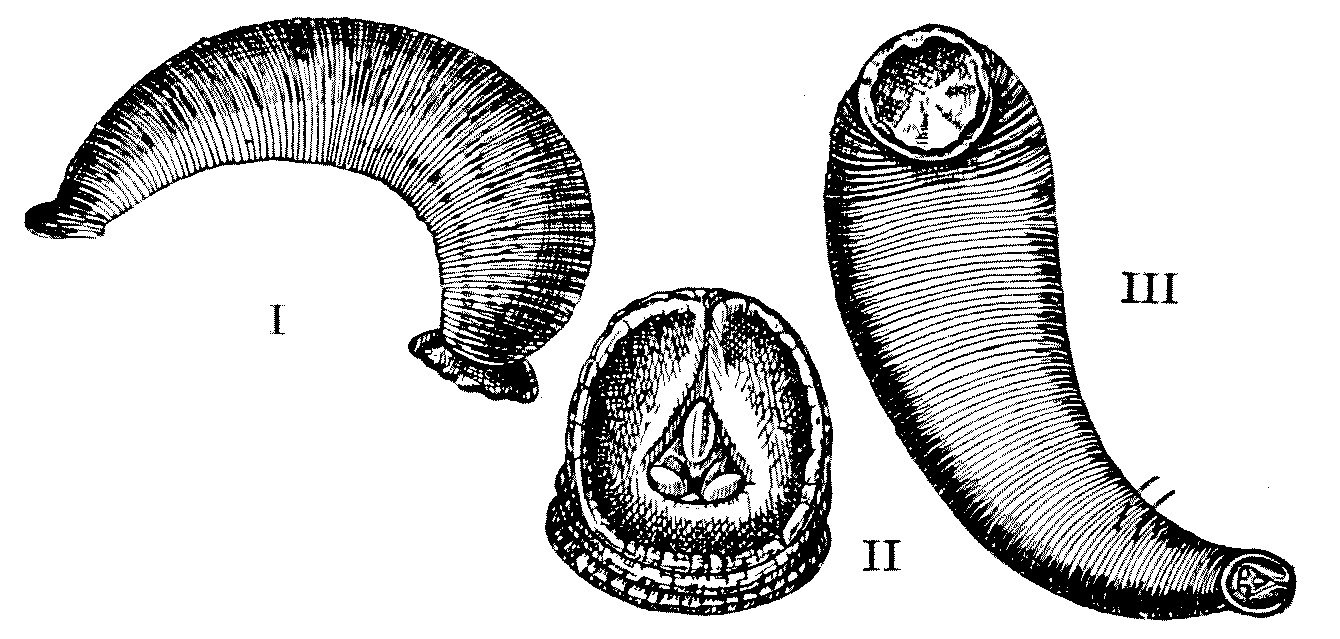

FIG. 61.—Haemadipsa zeylanica, seen from above. × 2. (From Blanchard.)

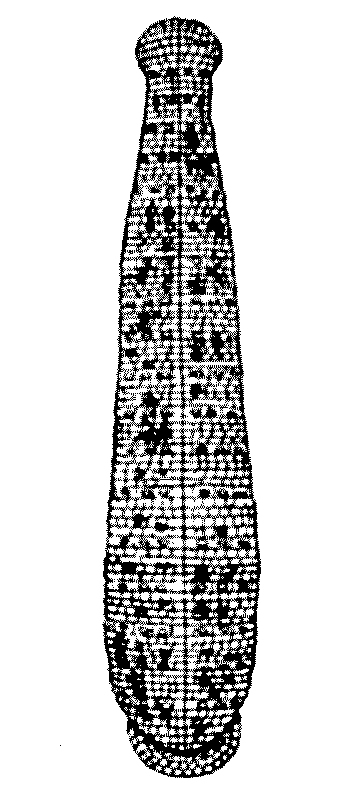

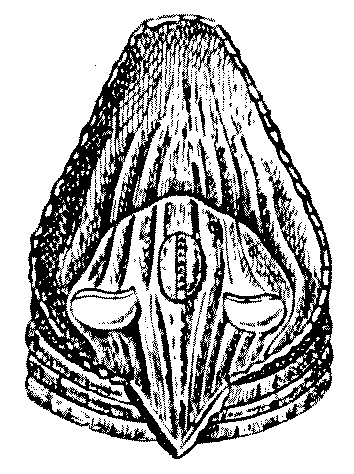

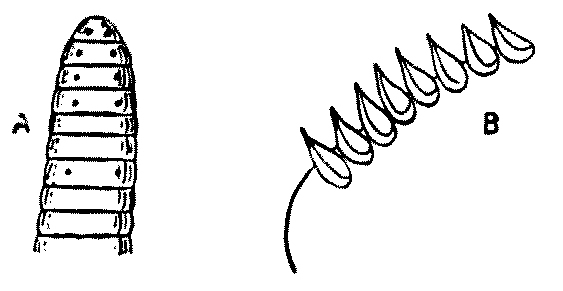

Each specimen of Haemadipsa zeylanica is of a clear brown colour with a yellow stripe on each side and with a greenish dorsal stripe. There are five pairs of eyes, of which the first four occupy contiguous rings; but between the fifth and seventh ring there are two eyeless rings interposed. As in the medicinal leech there are three teeth, each serrated like a saw.

In dry weather they miraculously disappear, and nobody seems to know quite what becomes of them; but with returning showers they are found again on the soil and on the lower vegetation in enormous profusion. Each leech is about one inch in length and is about as thick as a knitting-needle. But they contract until they attain the diameter of a quill pen, or extend their bodies until they have doubled their normal length. They are the most insinuating of creatures, and can force their way through the interstices of the tightest laced boot, or between the folds of the most closely wound puttee. Making their tortuous way towards the human skin, they wriggle about under the under-clothing until they attain almost any position on the body they wish to take up. Their bite is absolutely painless, and it is usual for the human sufferer to become aware that he has been bitten by these silent and tireless leeches when he notices sundry streams of blood running down his body when he at last has the opportunity of undressing.

FIG. 62.—Haemadipsa zeylanica. Head, showing the eyes and the serrations of the jaw. Highly magnified. (From Tennant.)

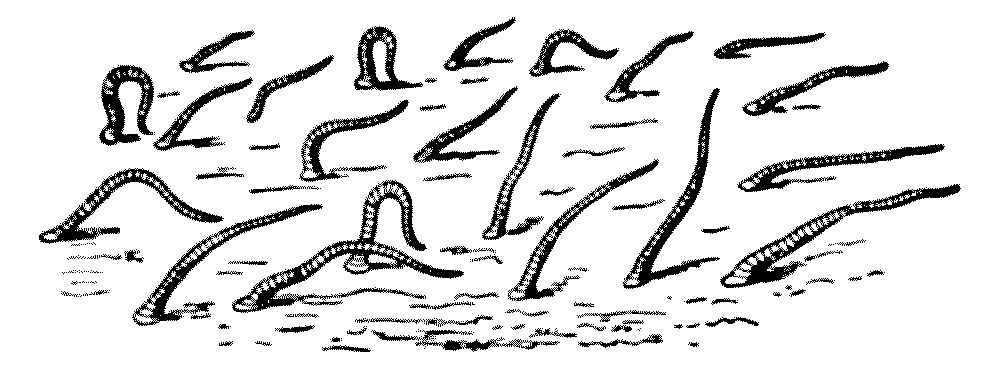

Sometimes, as Tennant’s figure shows, these land-leeches (H. zeylanica) rest upon the ground. At other times they ascend the leaves of herbs and grasses, and especially the twigs of the forest undergrowth. Perched upon the ends of growing shoots, leaves, and twigs, stretching their quivering bodies into the void, they eagerly watch and wait the approach of some travelling mammal. They easily ‘scent’ their prey, and on its approach advance upon it with surprising rapidity in semicircular loops. A whole and vast colony of land-leeches is set in motion without a moment’s delay, and thus it comes about that the last of a travelling or prospecting party in a land-leech area invariably fares the worst, as these land-leeches mobilise and congregate with extraordinary rapidity when once they are warned of the approach of a possible host, but not always in time to engage in numbers the advanced guard.

FIG. 63.—Haemadipsa zeylanica (land-leeches), on the earth. (From Tennant.)

Horses are driven wild by them, and have poor means of reprisal. They stamp their hooves violently on the ground in the hope of ridding their fetlocks of these tangled masses of bloody tassels. The bare legs of the natives, who carry palanquins, are particularly subject to the bites of these bloodthirsty brutes, as the palanquin-bearer has no free hand to pick them off. Tennant writes that he has actually seen the blood welling over the boots of a European from the innumerable bites of these land-leeches; and it is on record that during the march of the troops in Ceylon, when the Kandyans were in rebellion, many of the Madras sepoys, and their coolies, perished from their innumerable and united attacks. It is also certain that men falling asleep over-night in a Cingalese forest have, so to speak, ‘woke up dead’ next morning. These sleepers have succumbed during the night to the repeated attacks of these intolerable and insatiable pests.

Dr. Charles Hose, for many years Resident at Sarawak, has told me that on approaching the edges of woods in Borneo you can hear every leaf rustling, and this is due to the fact that the eager leech, perched on its posterior sucker on the edge of each leaf in the undergrowth, is swaying its body up and down, yearning with an ‘unutterable yearning,’ to get at the integument of man or some other mammal.

Landor, who wrote, I think, the best book about our adventure into Thibet some ten years ago, entitled ‘Lhassa’ (London, 1905), says of Sikkim:—

The game here is very scanty: the reason is not uninteresting. For dormant or active, visible or invisible, the curse of Sikkim waits for its warm-blooded visitor. The leeches of these lovely valleys have been described again and again by travellers. Unfortunately the description, however true in every particular, has, as a rule, but wrecked the reputation of the chronicler. Englishmen cannot understand these pests of the mountain-side, which appear in March, and exist, like black threads fringing every leaf, till September kills them in myriad millions.

To remove them a bowl of warm milk at the cow’s nose, a little slip-knot, and a quick hand are all that is required. Fourteen or fifteen successively have been thus taken from the nostrils of one unfortunate heifer.

When fully fed, a process which takes some time with Haemadipsa zeylanica, the individual leeches drop off; and they can be made to loosen their hold by the application of a solution of salt or of weak acid. Attempts to pull them off should be avoided, as parts of the biting apparatus are then often left in the wound, and these may cause inflammation and suppuration. Dr. R. J. Drummond, who has had experience of these land-leeches in Ceylon, has told me that the bite is often septic and that it often leads to a serious abscess which is long in healing. He recommends pushing a match, which has been dipped into carbolic acid, well home into the sinus made by the leech’s head.

When winter approaches the leeches die down with extraordinary rapidity, and the species ‘carry on’ over the cold-weather period in the form of eggs laid in cocoons on the ground, under leaves, or other débris. Hence no land-leech ever sees its offspring, and no land-leech has ever known a mother’s care.