CHAPTER XI

LEECHES

PART II

THE MEDICINAL LEECH (Hirudo medicinalis)—continued

Non missura cutem, nisi plena cruoris, hirudo.

(HORACE.)

THERE is no doubt that the medicinal leech is one of the most beautiful of animals. Many of its cousins are uniform and dull in colour—‘self-coloured,’ as the drapers would call them; but the coloration of the medicinal leech could not be improved upon. It is a delicious harmony of reddish-browns and greens and blacks and yellows, a beautiful soft symphony of velvety orange and green and black, the markings being repeated on each segment, but not to the extent of a tedious repetition. So beautiful are they that the fastidious ladies who adorned the salons at the height of the leech mania, during the beginning of the eighteenth century, used to deck their dresses with embroidered leeches, and by repeating the design one after the other constructed a chain of leeches which, as a ribbon, was inserted around the confines of their vesture.

Harding tells us that the dorsal surface of H. medicinalis is ‘usually of a green, richly variegated colour, with orange and black spots, exhibiting an extremely variable pattern, based generally upon three pairs of reddish-brown or yellowish, more of less, longitudinal stripes, often interrupted by black or sessile spots occurring on the rim of each somite. The ventral surface is more or less green, more or less spotted with black, with a pair of black marginal stripes.’

The shape of the medicinal leech, and indeed of other leeches, is difficult to put into figures, as their bodies are as extensile as the conscience of a politician and as flexible as that of a candidate for parliamentary honours. The length of H. medicinalis in extreme extension is said to range from some 100 mm. to 125 mm.; in extreme constriction from 30 mm. to 35 mm. The width in the former state would be 8 mm. to 10 mm., and in the latter 15 mm. to 18 mm.

The movements of the medicinal leech are as graceful as its colour is tasteful. When in the water they move like looper-caterpillars (Geometrids), stretching out their anterior sucker, attaching it to some object, and then releasing the posterior sucker they draw the body up towards the mouth. Or, casting loose from all attachment, the leech elongates and at the same time flattens its body until it assumes the shape of a band or short piece of red tape, and by a series of the most seductive undulations swims through the water. Kept in an aquarium they are rather apt at times to leave the water and take up a position on the sides of their home an inch or two above the aqueous surface. When outside the water they keep their bodies moist by the excretion of their nephridia or kidneys. This fluid plays the same part on the skin of a leech as the coelomic fluid of an earthworm, which escapes by the earthworm’s dorsal pores. There is very little doubt that both these fluids contain some bactericidal toxin which prevents epizootic protozoa and bacteria from settling on their skins. Such external parasites settle on many fresh-water crustacea—such as Cyclops, which is a floating aquarium of Ciliata. In fact, leeches, like earthworms, have a self-respecting, well-groomed external appearance. Like our dear soldiers, they are, so to speak, always clean shaven.

There has been a very widely spread tradition that in their comings and goings in and out of the water, leeches act as weather prophets. The poet Cowper, who throughout his chequered career ever showed but an imperfect sympathy with science, tells us that ‘leeches in point of the earliest intelligences are worth all the barometers in the world’; and Dr. J. Foster mentions that leeches, ‘confined in a glass of water, by their motions foretell rain and wind, before which they seem much agitated, particularly before thunder and lightning.’ Modern opinion, however, prefers the barometer.

The great Chancellor, Lord Erskine, kept a couple of tame leeches and Sir Samuel Romilly records the fact in one of his decorous letters:—

He told us how that he had got two favourite leeches. He had been blooded by them last autumn when he had been taken dangerously ill at Portsmouth; they had saved his life, and he had brought them with him to town, had ever since kept them in a glass, had himself every day given them fresh water, and had formed a friendship with them. He said he was sure they both knew him, and were grateful to him. He had given them different names, Home and Cline (the names of two celebrated surgeons), their dispositions being quite different. After a good deal of conversation about them, he went himself, brought them out of his library, and placed them in their glass upon the table. It is impossible, however, without the vivacity, the tones, the details, and the gestures of Lord Erskine, to give an adequate idea of this singular scene. He would produce his leeches at consultation under the name of ‘bottle conjurers,’ and argue the result of the cause according to the manner in which they swam or crawled.[15]

The medicinal leech lives on the blood of vertebrates and invertebrates. Mr. H. O. Latter records that ‘cattle, birds, frogs and tadpoles, snails, insects, small soft-bodied crustacea, and worms are all attacked by various species’ of leech; but the true food of Hirudo medicinalis is the blood of vertebrates. The three teeth, which cause the well-known triradiate mark on the skin, are serrated and sharp. The strong sucking-pharynx has its wall attached by numerous muscles to the underside of the skin of the leech. By the contraction of these muscles its lumen is enlarged, and by thus creating a vacuum the blood of the host flows in.

In the walls of the pharynx and the neighbouring parts are numerous large unicellular glands which secrete an anti-coaguline fluid which prevents the blood of the host clotting, so that even when the leech moves its mouth to another point the triradiate puncture continues to ooze. The same anti-coaguline secretion no doubt prevents the blood coagulating in the enormous crop of the leech in which this meal of blood is stored. Opportunities for a meal presumably occur but seldom in nature, and the leech is the ‘boa-constrictor’ of the invertebrate world. Its interior economy is laid out on the basis of a large and capacious storage and of a very restricted and very slow digestion. The blood sucked into the sucking-pharynx passes on to the thin-walled crop, which occupies almost all of the space in the animal. This crop is sacculated, having eleven large lateral diverticula on each side. In a fed leech the whole of this crop is swollen with blood, which, as we have said above, does not coagulate. The actual area where the digestion takes place is ludicrously small, as shown at 5, Fig. 49, p. 126. The rectum, which runs from the real seat of assimilation to the opening of the posterior sucker, transmits the undigested food—but there is not much of it.

An active medicinal leech will draw from one to two drams of blood, and as much more will flow from the wound when the leech moves, because the coagulation of the blood has been put out of action. No scab or clot is formed. If necessary, the flow of blood can be stimulated by hot fomentations. Sometimes the bleeding is so great that artificial means have to be taken to check it. When leeches are applied to the human integument they are generally first dried in a cloth, and if they will not bite the part required, the part should be moistened with sweetened milk or a drop of blood. To remove leeches when replete, salt, sugar, or snuff sprinkled over the back is used. They may then be made to disgorge by placing them in a salt solution of 16 parts salt and 100 of water at 100° F. A full meal is said to last leeches nine months.

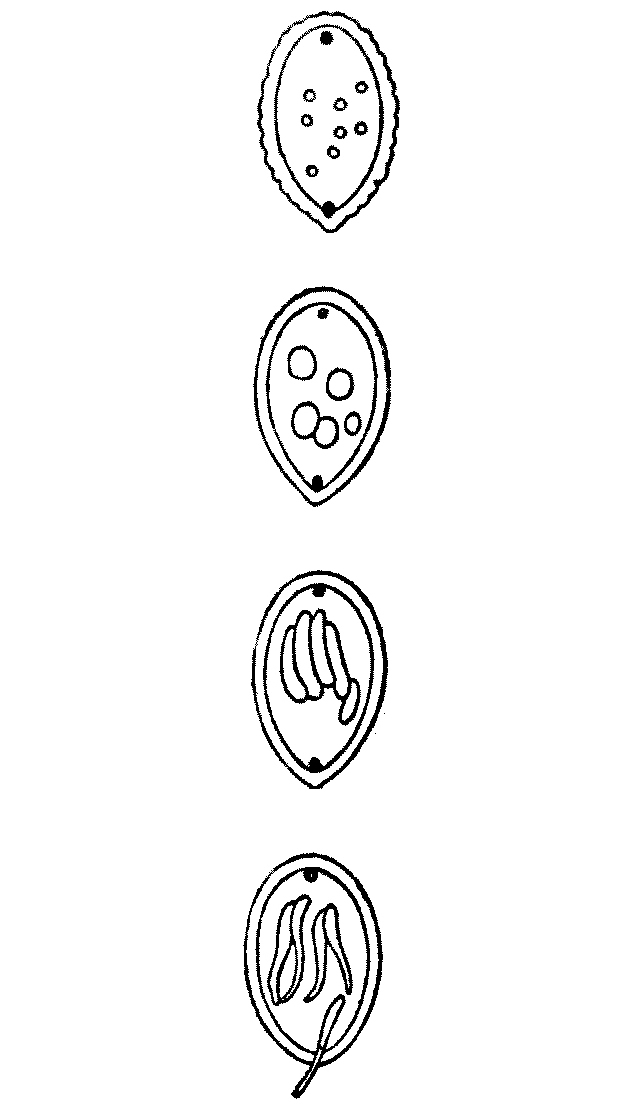

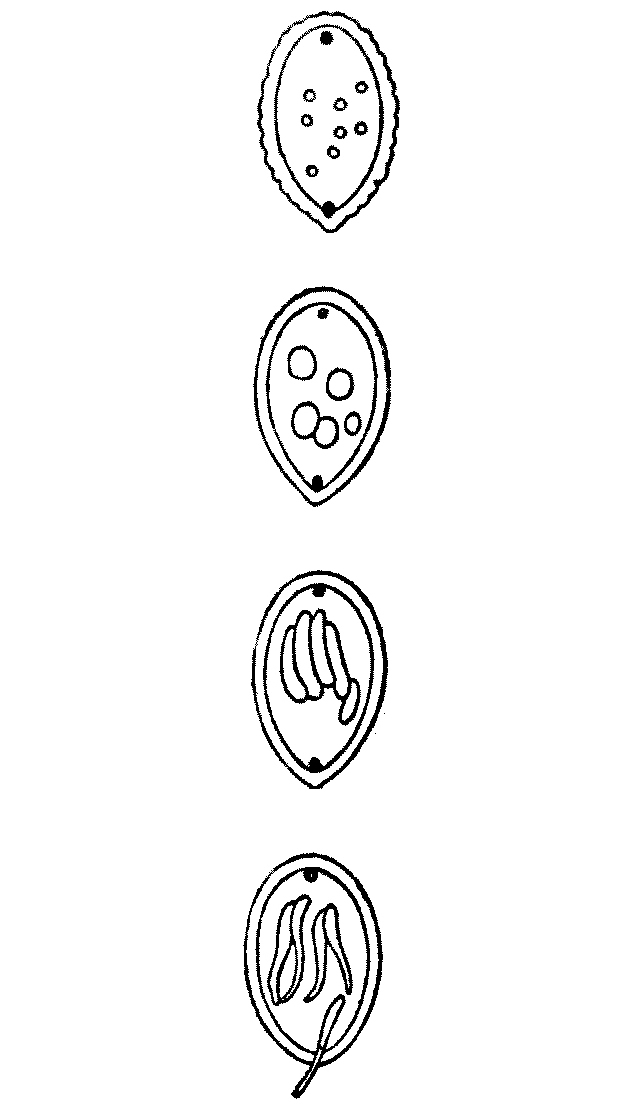

FIG. 52.—Cocoon of the medicinal leech, and longitudinal and transverse views of the same cut open.

Leeches are hermaphrodite; and in some genera the acting male inserts spermatophores, or little cases containing spermatozoa, anywhere in the skin of the leech that is being fertilised, and the spermatozoa then make their way through the tissues of the body of the potential female till they arrive at the ovary and there fuse with the ova. In the medicinal leech the mating is said to be encouraged by adding fresh water to the vessels in which the leeches are living.

The eggs are laid in capsules or cocoons attached to some water-plant or buried in the mud, about twenty-four hours after the leeches have mated. The cocoon is formed, as it is in an earthworm, by certain glands in the skin which form a secretion that hardens and takes the form of a broad ring, as it were, round the body of the leech.

FIG. 53.—A Nephelis forming its cocoon and withdrawing from it.

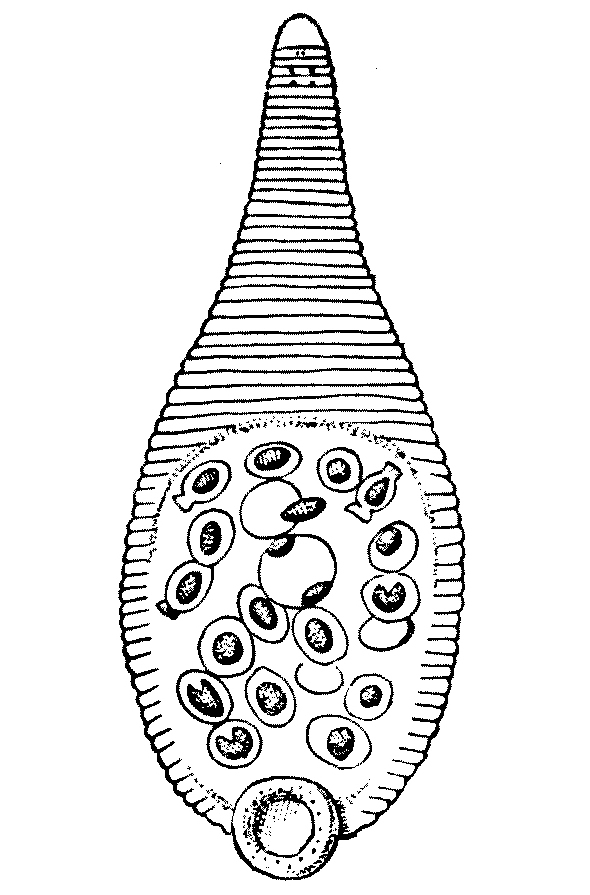

Through this broad ring the body of the leech is withdrawn and the fertilised eggs are deposited in it. The two ends close up, but not entirely, for the young leeches eventually make their way into the outer water through one of the remaining pores. Within the cocoon are six to twenty ova, and these gradually mature and the young hatch out. When they leave the cocoon they are minute, and of the thickness of pack-thread. More than one cocoon is deposited by each leech, but unless the cocoons are anchored to some submerged object they often rise to the surface of the water and float half submerged, and are then apt to be destroyed by water-rats, voles, and other enemies of leeches. At times the leeches themselves destroy their cocoons.

FIG. 54.—Cocoons of Nephelis, showing the growth of the eggs and the issuing larvae, which in the lower figure are leaving the cocoons.

The exact time of the emergence from the cocoon does not seem to be very definitely known, but leeches are long-lived annelids. It is not till their third year that they are of any use for medicinal purposes, and they are said not to pair until they are six or seven years old. They certainly live twelve or fifteen years. But, if we adopt an optimistic view—and in this little book we do—the fact that they grow up so slowly and live so long shows that it will be difficult to replace the shortage of leeches in Great Britain and Ireland during the present war. This could hardly be done by home culture, for even if the war lasts three or four years we have lost the cocoons of the summer of 1914, even if we ever had them.

Leeches have many enemies:— water-rats, voles, the larvae of the Dytiscus beetle, the larvae of Hydrophylus, the Nepa or water-scorpion, the larvae of the dragonfly, and the adult Dytiscus—all feed upon them. Many birds also eat leeches; and it is recorded that at one artificial leech-farm, where there were 20,000 leeches, they were all eaten up in twenty-four hours by an invasion of ducks. Frogs and newts also devour them, and they are not above eating their own brothers. Aulostoma will devour its own species as readily as it will an earthworm.

Those artificially reared, as is usually the case with animals reared in captivity—probably against their will—are peculiarly liable to disease of various sorts. They not only become diseased themselves, but they act as carriers of disease and play the same part to fish which biting insects play to man and other terrestrial animals. They convey to fishes protozoal diseases similar to those that insects convey to man and other warm-blooded vertebrates.

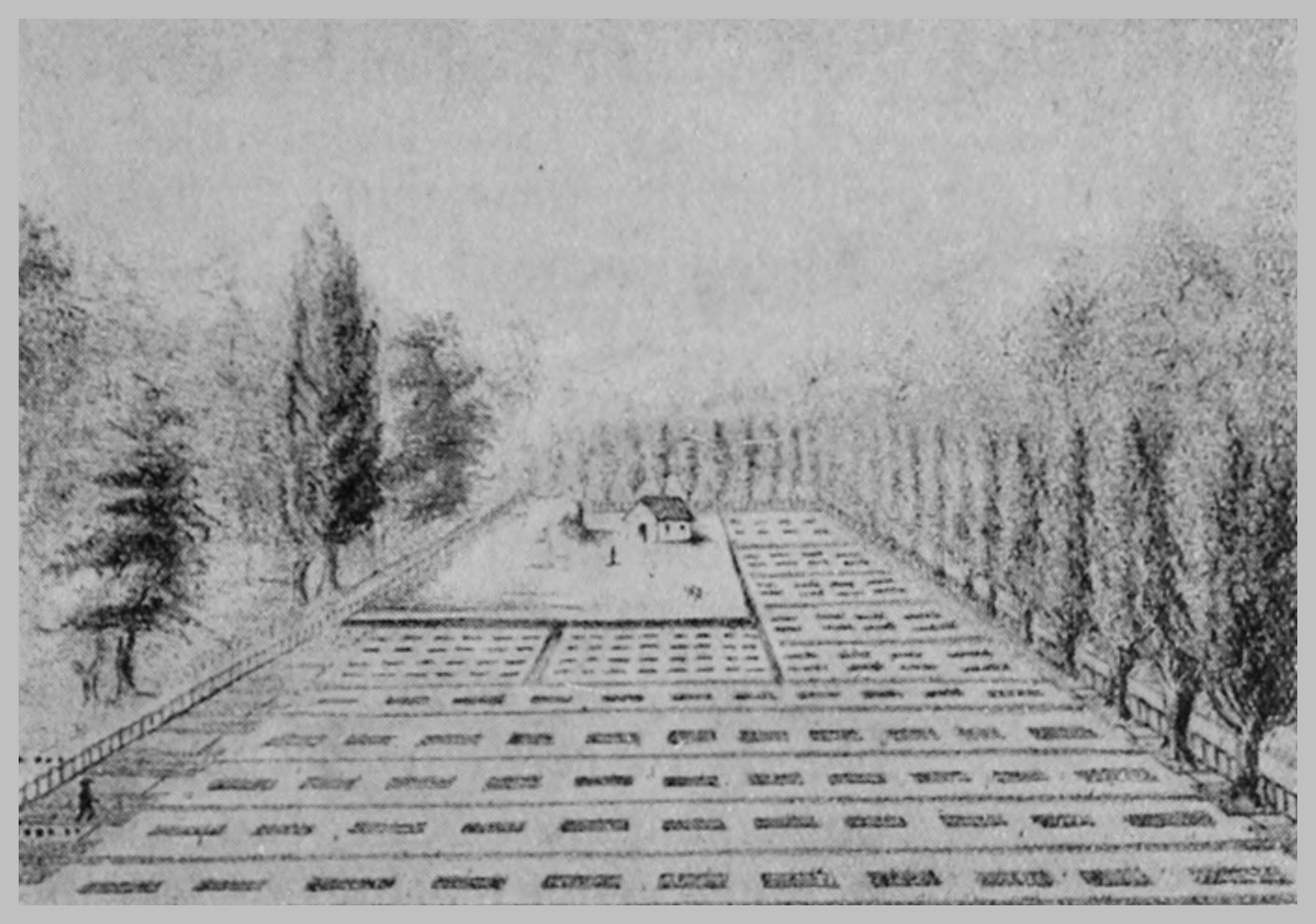

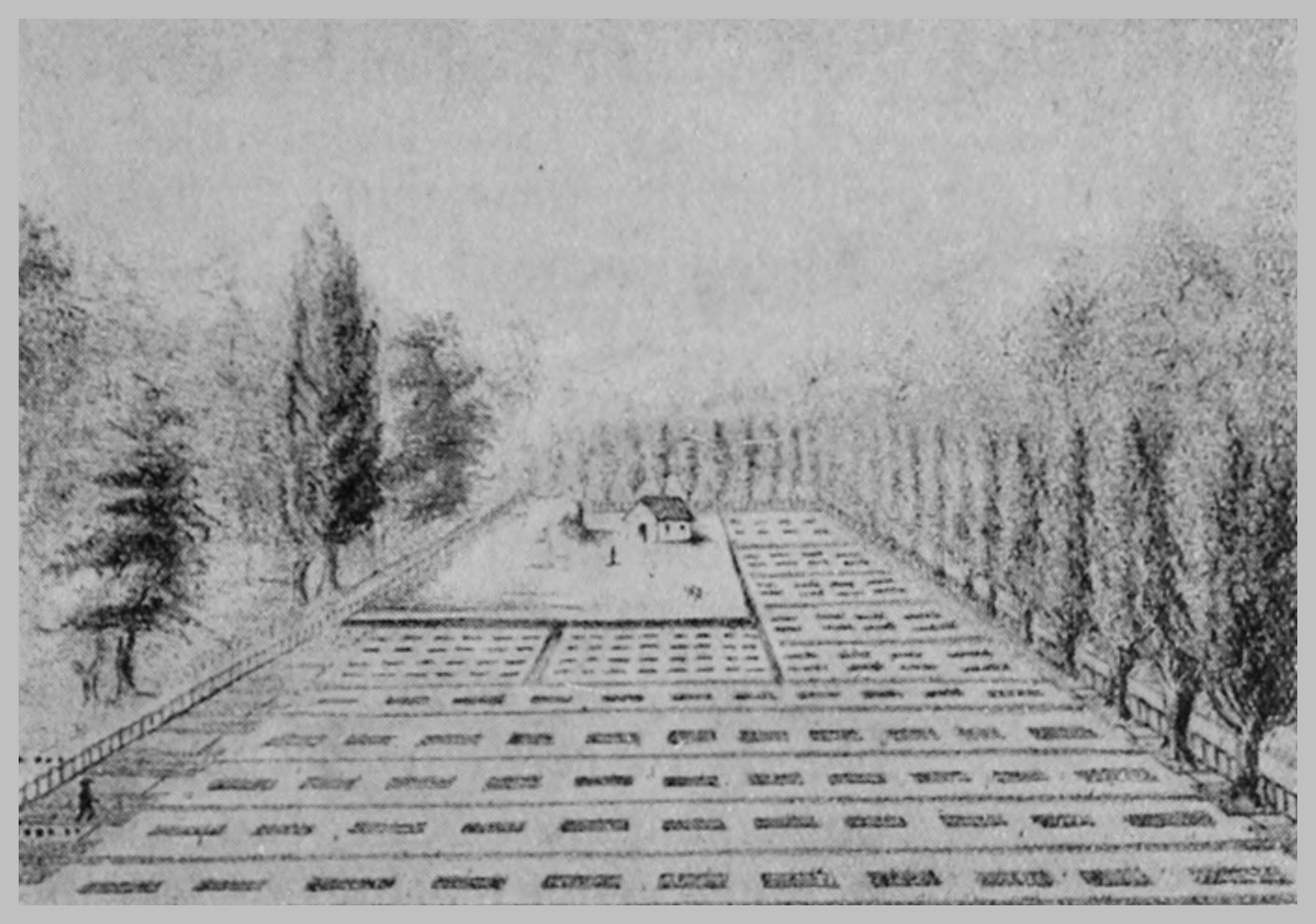

FIG. 55.—A leech-farm in the south of France.

Leech-farming used to be a profitable undertaking, but now it has fallen into desuetude in these islands. Leeches are, however, still cultivated in some parts of the world; and in America, Latter describes a farm, situated at Newton in Long Island, where there is, or was, a leech-farm some thirteen acres in extent. The farm consists of oblong ponds of about one and a half acres, each three feet deep. The bottom of each pond is covered with clay, and the banks are made of peat. The French writers recommend, as a rule, the use of clay for the banks. The ‘eggs’ (cocoons) are deposited in the peat from June onwards, till the weather gets chilly. The adult leeches are fed every six months with fresh blood placed in stout linen bags suspended in the water. A more cruel method of feeding these domesticated leeches is that of driving horses, asses, or cattle into the ponds—and this was the custom in France.

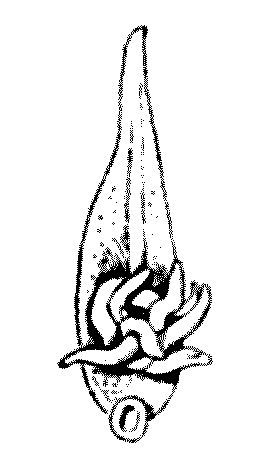

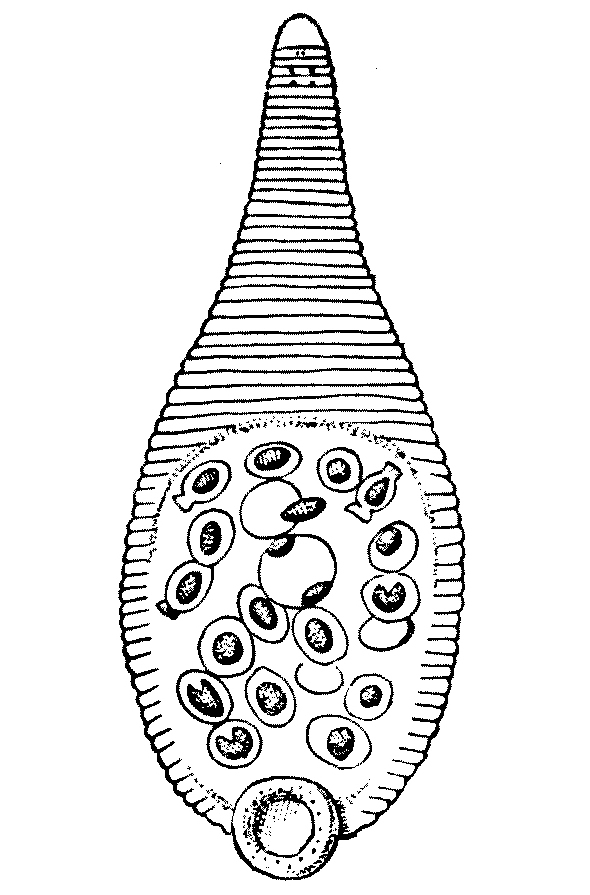

FIG. 56.—Glossosiphonia heteroclita, with eggs and emerging embryos. Ventral view. × 4. (From Harding.)

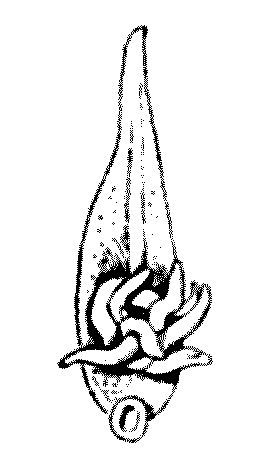

FIG. 57.—Helobdella stagnalis, with adhering young. Ventral view, magnified. (From Harding.)

Some leeches show a considerable amount of maternal affection. Glossosiphonia heteroclita, for instance, carries its eggs about with it, and Helobdella stagnalis has its little young larvae attached by their tiny suckers to the mother’s body, which they are loath to leave.

Aulostoma gulo, the horse-leech, is notoriously a very ferocious feeder. Exactly why this species is called a horse-leech is a matter of speculation; but ‘horse’ used as an adjective seems to imply something large and something rather coarse—for instance, horse-chestnuts, horse-play, horse-sense, and horse-laugh.

The rapacity of the daughters of the ‘horse-leach’ is dwelt on in the Bible.[16] I am not an authority on exegesis, but I have never felt quite sure whether these two ladies were not the offspring of the local veterinary surgeon. But Aulostoma does occur in Palestine, and its voracity may very well have been known to the Hebrews. I entirely reject the idea that the word indicates some ghost or phantom: that explanation is due to the craven policy of taking refuge in the unknown.

I conclude this chapter with a couple of sentences taken from Dr. Phillips’s ‘Materia Medica’ on the present use of leeches:—

The special value of leeching is shown in the early stage of local congestion and inflammations: such as arise from injuries, and in orchitis, laryngitis, haemorrhoids, and inflammations of the ear and eye, cerebral congestions, and congestive fixed headache.

Leeches are also of service, in a manner less easy to understand, in inflammations of deep-seated parts without direct vascular connexion with the surface—for example, in hepatitis, pleuritis, and pericarditis, as well as in pneumonia, peritonitis, and, according to some observers, in meningitis. In all these disorders, however, they are very much less used than formerly—in the larger hospitals, for instance, when at one time they cost many hundred pounds annually, a few dozens in the year would represent the total employed.[17]