CHAPTER I

THE LOUSE (Pediculus)

Care’ll kill a cat, up-tailles all and a louse for the hangman!

(B. JONSON, Every Man in his Humour.)

LICE form a small group of insects known as the Anoplura, interesting to the entomologist because they are now entirely wingless, though it is believed that their ancestry were winged. They are all parasites on vertebrates. In quite recent books the Anoplura are described as ‘lice or disgusting insects, about which little is known’; but lately, owing to researches carried on at Cambridge, we have found out something about their habits. As lice play a large part in the minor discomforts of an army, it is worth while considering for a moment what we know about them.

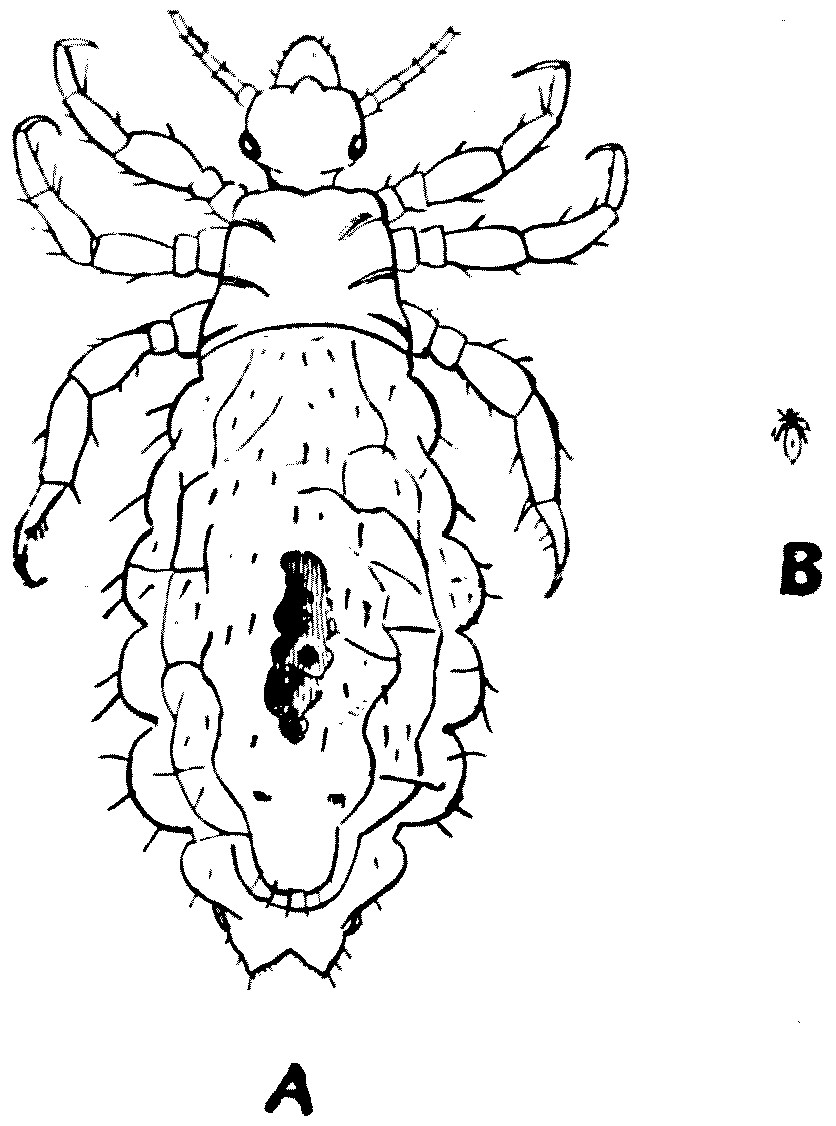

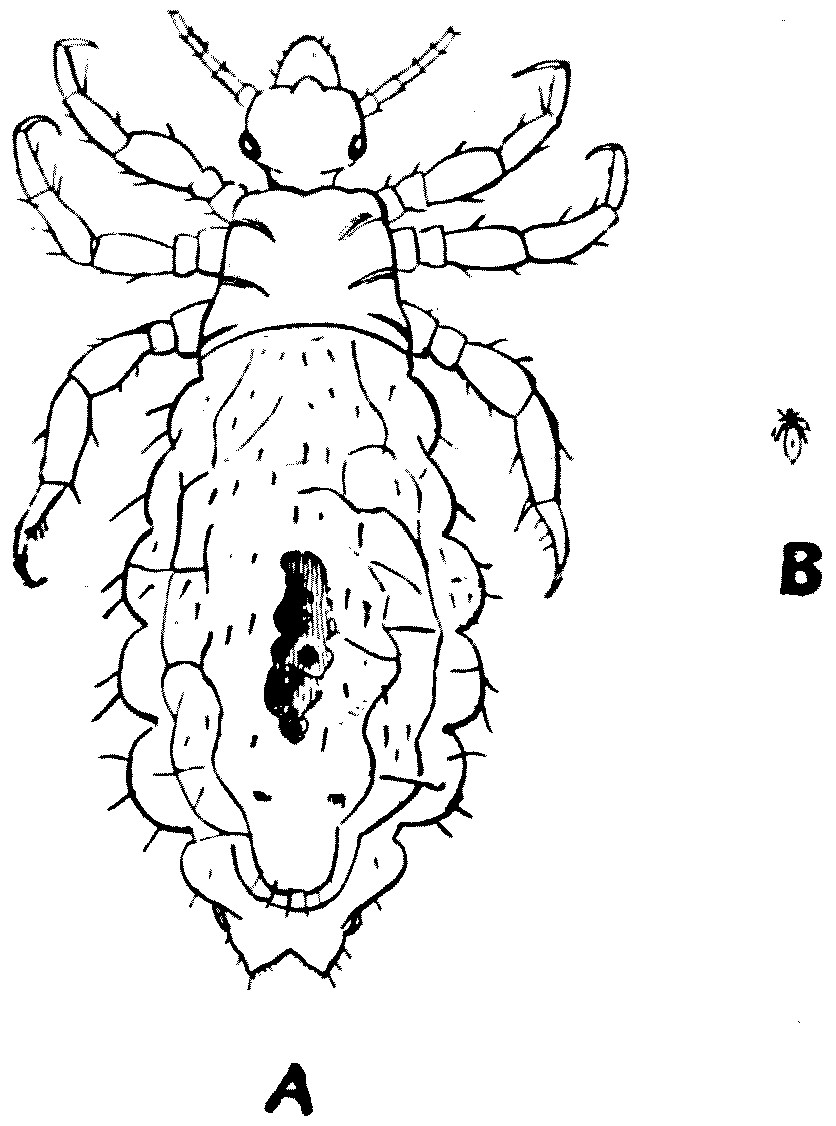

FIG. 1.—Pediculus vestimenti (Nitzsch). A, Magnified 20 times; B, natural size.

Recently, the group has been split up into a large number of genera, but of these only two have any relation to the human body. I do not propose, in the present chapter, to consider one of these two genera—Phthirius—which frequents the hairs about the pubic region of man and is conveyed from one human being to another by personal contact. We will confine our attention to the second genus, Pediculus, which contains two species parasitic upon man—(Pediculus capitis) the hair-louse and (Pediculus vestimenti) the body-louse. Both of these are extremely difficult to rear in captivity, though in their natural state they abound and multiply to an amazing degree.

Wherever human beings are gathered together in large numbers, with infrequent opportunities of changing their clothes, P. vestimenti is sure to spread. It does not arise, as the uninformed think, from dirt, though it flourishes best in dirty surroundings. No specimen of P. vestimenti exists which is not the direct product of an egg laid by a mother-louse and fertilised by a father-louse. In considerable collections of men drawn from the poorer classes, some unhappy being or other—often through no fault of his own—will turn up in the community with lice on him, and these swiftly spread to others in a manner that will be indicated later in this chapter.

Like almost all animals lower than the mammals, the male of the body-louse is smaller and feebler than the female. The former attains a length of about 3 mm., and is about 1 mm. broad. The female is about 3·3 mm. long and about 1·4 mm. broad. It is rather bigger than the hair-louse, and its antennae are slightly longer. It so far flatters its host as to imitate the colour of the skin upon which it lives; and Andrew Murray gives a series of gradations between the black louse of the West African and Australian native, the dark and smoky louse of the Hindu, the orange of the Africander and of the Hottentot, the yellowish-brown of the Japanese and Chinese, the dark-brown of the North and South American Indians, and the paler-brown of the Esquimo, which approaches the light dirty-grey colour of the European parasites.

As plump an’ grey as onie grozet,

as Burns has it.

The latter were the forms dealt with in the recent observations undertaken by Mr. C. Warburton in the Quick Laboratory at Cambridge, at the request of the Local Government Board, the authorities of which were anxious to find out whether the flock used in making cheap bedding was instrumental in distributing vermin. Mr. Warburton at once appreciated the fact that he must know the life-history of the insect before he could successfully attack the problem put before him. At an early stage of his investigations, he found that P. vestimenti survives longer under adverse conditions than P. capitis, the head-louse.

The habitat of the body-louse is that side of the under-clothing which is in contact with the body. The louse, which sucks the blood of its host at least twice a day, is when feeding always anchored to the inside of the under-clothing of its host by the claws of one or more of its six legs. Free lice are rarely found on the skin in western Europeans; but doctors who have recently returned from Serbia report dark-brown patches, as big as half-crowns, on the skins of the wounded natives, which on touching begin to move—a clotted scab of lice! But the under-side of a stripped shirt is often alive with them.

After a great many experiments, Mr. Warburton succeeded in rearing these delicate insects, but only under certain circumscribed conditions: one of which was their anchorage in some sort of flannel or cloth, and the second was proximity to the human skin. He anchored his specimens on small pieces of cloth which he interned in small test-tubes plugged with cotton-wool, which did not let the lice out, but did let air and the emanations of the human body in. For fear of breakage the glass tube was enclosed in an outer metal tube, and the whole was kept both night and day near the body. Two meals a day were necessary to keep the lice alive. When feeding, the pieces of cloth, which the lice would never let go of, were placed on the back of the hand, hence the danger of escape was practically nil, and once given access to the skin the lice fed immediately and greedily.

His success in keeping lice alive was but the final result of many experiments, the majority of which had failed. Lice are very difficult to rear. When you want them to live they die; and when you want them to die they live, and multiply exceedingly.

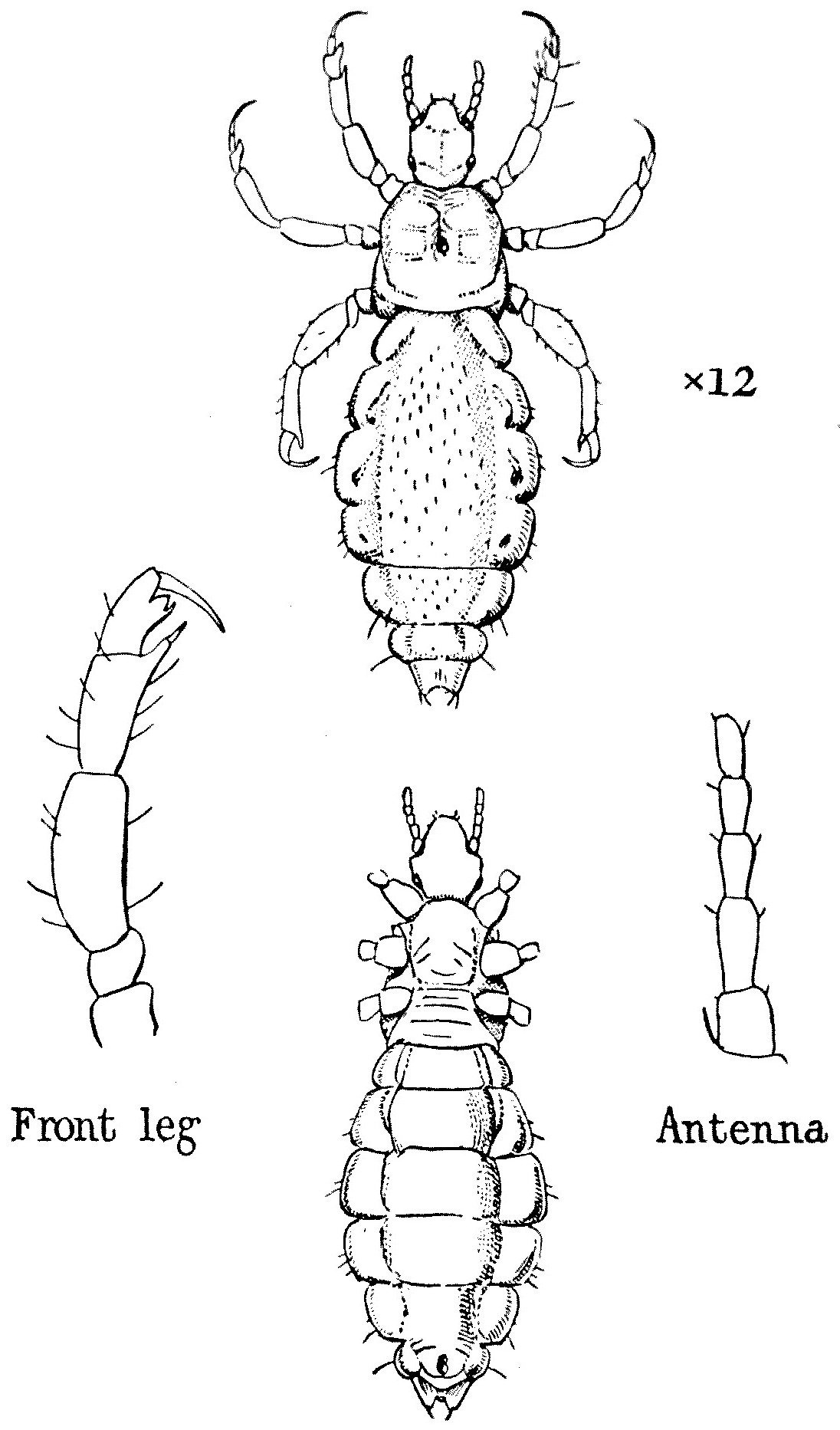

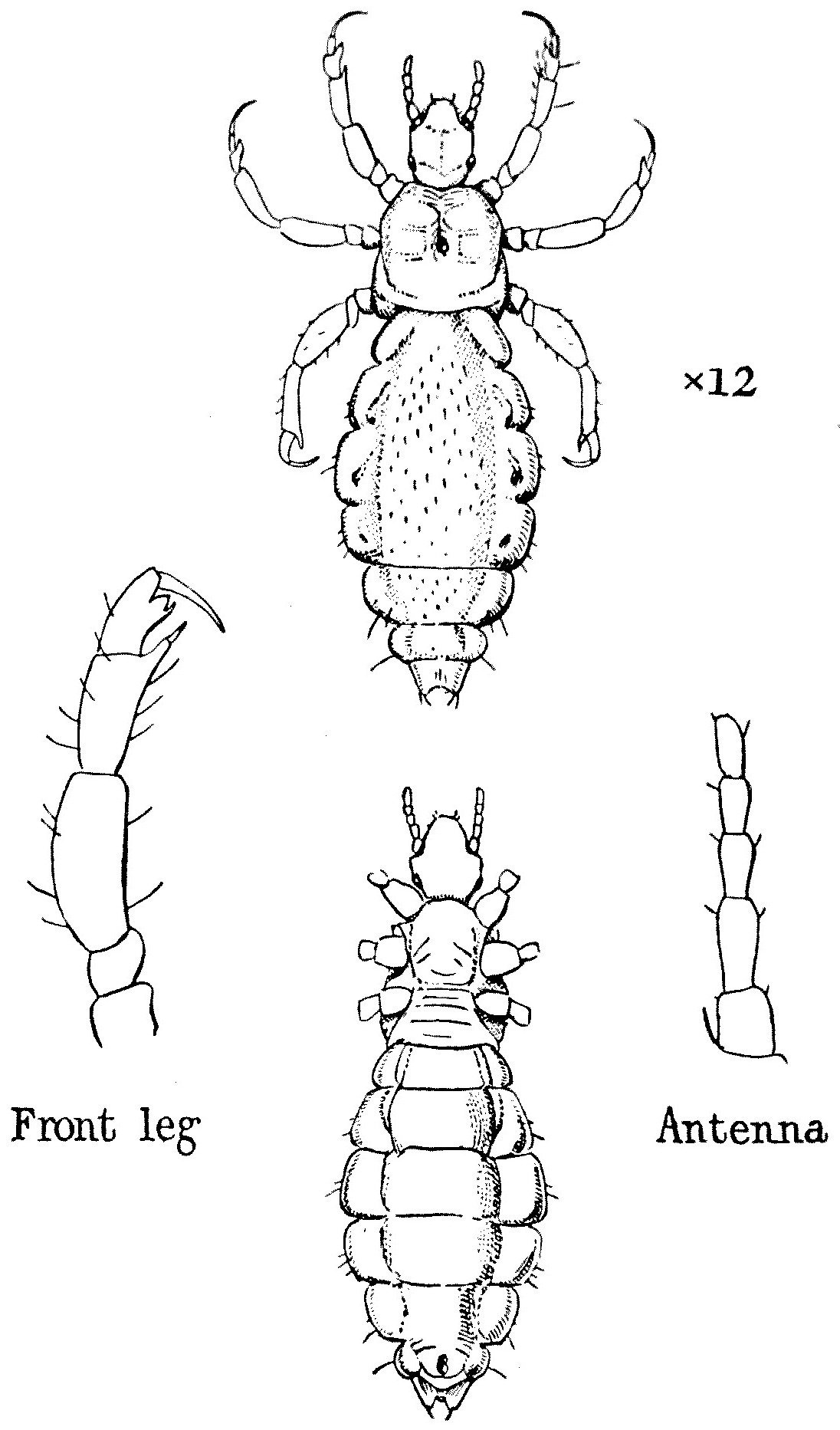

FIG. 2.—Pediculus vestimenti. Dorsal and ventral views.

A single female but recently matured was placed in a test-tube, and a male admitted to her on the second day. The two paired on the sixth day and afterwards at frequent intervals. Very soon after pairing an egg was laid, and during the remaining twenty-five days of her life the female laid an average of five eggs every twenty-four hours. The male died on the seventeenth day, and a second male was then introduced, who again paired with the female. The latter, however, died on the thirtieth day, but the second male survived.

The difficulty of keeping the male and female alive was simple compared with the difficulty of rearing the eggs. Very few hatched out. The strands of cloth upon which they were laid had been carefully removed and placed in separate tubes, at the same time being subjected to different temperatures. It was not, however, until the eggs were left alone undisturbed in the position where they had been laid and placed under the same conditions that the mother lived in that eight, and only eight, of the twenty-four eggs laid on the cloth hatched out after an incubation period of eight days. The remaining sixteen eggs were apparently dead. But the tube in which they were was then subjected to normal temperature of the room at night (on occasions this fell below freezing-point), and after an incubation period of upwards of a month six more hatched out. Hence it is obvious that, as in the case of many other insects, temperature plays a large part in the rate of development, and it becomes clear that the eggs or nits of P. vestimenti are capable of hatching out up to a period of at least from thirty-five to forty days after they are laid.

Difficult as it was to keep the adults alive, and more difficult as it was to hatch out the eggs, it was most difficult to rear the larvae. Their small size made them difficult to observe, and, like most young animals, they are intolerant of control, apt to wander and explore, and less given to clinging to the cloth than their more sedentary parents. Naturally, they want to scatter, spread themselves, and pair.

Like young chickens, the larvae feed immediately on emerging from the egg. They apparently moult three times, at intervals of about four days, and on the eleventh day attain their mature form, though they do not pair until four or five days later.

Mr. Warburton summarises the life-cycle of the insects, as indicated by his experiments, as follows:—

Incubation period: eight days to five weeks.

From larva to imago: eleven days.

Non-functional mature condition: four days.

Adult life: male, three weeks; female, four weeks.

But we must not forget that these figures are based upon laboratory experiments, and that under the normal conditions the rate may be accelerated. From Mr. Warburton’s experience it is perfectly obvious that, unless regularly fed, body-lice very quickly die. Of all the verminous clothing sent to the Quick Laboratory, very little contained live vermin. The newly hatched larvae perish in a day and a half unless they can obtain food.

With regard to the head-louse:—

Ye ugly, creepin’, blastit wonner,

Detested, shunn’d by saunt an’ sinner,

it is smaller than the body-louse, and is of a cindery grey colour. The female measures 1·8 mm. in length and 0·7 in breadth. Like the body-louse, it varies its colour somewhat with the colour of the hair on the different branches of the human race. It lives amongst the hair of the head of people who neglect their heads; it is also, but more rarely, found amongst the eyelashes and in the beard. The egg, which has a certain beauty of symmetry, is cemented to the hair, and at the end of six days the larvae emerge, which, after a certain number of moults, become mature on the eighteenth day. The methods adopted by many natives of plastering their hair with coloured clay, or of anointing it with ointments, probably guards against the presence of these parasites. The Spartan youths, who used to oil their long locks before going into battle, may have feared this parasite. Some German soldiers, before going to war, shave their heads: thus they afford no nidus for P. capitis. The wigs worn in the late seventeenth and at the beginning of the eighteenth centuries undoubtedly owed something to the difficulty of keeping this particular kind of vermin down. The later powdering of the hair may have been due to the same cause.

This book, however, attempts to deal more with the troubles of the camp, and P. capitis is in war time less important than P. vestimenti. The former certainly causes a certain skin trouble, but the latter not only affords constant irritation, but, like most biting insects, from time to time conveys most serious diseases. P. vestimenti is said to be the carrier of typhus. This was, I believe, first demonstrated in Algeria, but was amply confirmed last year in Ireland, when a serious outbreak of this fever took place, though little was heard of it in England. Possibly, P. capitis also conveys typhus, but undoubtedly both convey certain forms of relapsing or recurrent fever. The irritation due to the body-louse weakens the host and prevents sleep, besides which there is a certain psychic disgust which causes many officers to fear lice more than they fear bullets. Lice are the constant accompaniment of all armies; and in the South African War as soon as a regiment halted they stripped to the skin, turned their clothes inside out, and picked the Anoplura off. As a private said to me: ‘We strips and we picks ’em off and places ’em in the sun, and it kind o’ breaks the little beggars’ ’earts!’

In conjunction with the Quick Professor of Biology at Cambridge, I have drawn up the following rules. None of them will be possible at all times, but some of them may be possible at some time in the campaign. At any rate, by acting on these rules, a relative of mine who took part in the South African War was able to escape the presence of lice on his body, and the General commanding his brigade told me on his return that he was the only officer—and in fact the only man—in the brigade who had so escaped.

HOW THE SOLDIER MAY GUARD HIMSELF AGAINST INFESTATION WITH LICE

In times of war, when men are aggregated in large numbers and personal cleanliness—but especially an adequate change of clothing—cannot be secured, infestation with lice commonly takes place. The prevalence of lice in troops in the South African War was a source of serious trouble in that their attacks caused much irritation to the skin and disturbed men’s sleep.

Lice occur chiefly on the body (Pediculus vestimenti) and head (P. capitis). They are small greyish-white insects. The female lays about sixty eggs during two weeks; the eggs hatch after nine to ten days. The lice are small at first; they undergo several moults and grow in size, sucking blood every few hours, and attain sexual maturity in about two weeks. The eggs will not develop unless maintained at a temperature of 22° C. or over—such as prevails in clothing worn on the human body or in the hair of the head. This is why, when clothing is worn continuously, men are more prone to become infested with lice derived from habitually unclean persons, their clothing, bedding, &c. P. capitis lives between the hair in the head, and the eggs, called ‘nits,’ are attached to the hairs. P. vestimenti lives in the clothing, to which it usually remains attached when feeding on man; it lays its eggs in the clothing, and usually retreats into the seams and permanent folds therein. This is of importance in considering the means of destroying lice.

To avoid these pests the following rules should be observed:—

1. Search your person as often as possible for signs of the presence of lice—that is, their bites. As soon as these are found, lose no time in taking the measures noted under paragraph 5.

2. Try not to sleep where others, especially the unclean, have slept before. Consider this in choosing a camping-ground.

3. Change your clothing as often as practicable. After clothes have been discarded for a week the lice are usually dead of starvation. Change clothes at night if possible, and place your clothing away from that of others. Jolting of carts in transport aids in spreading the lice, which also become disseminated by crawling about from one kit to another. Infested clothing and blankets, until dealt with, should be kept apart as far as possible.

4. Verminous clothes for which there is no further use should be burnt, buried, or sunk in water.

5. If lice are found on the person, they may be readily destroyed by the application of either petrol, paraffin oil, turpentine, xylol, or benzine. Apply these to the head in the case of P. capitis. Remember that these fluids are all highly inflammable. When possible, soap and wash the head twenty-four hours after the last application of petrol, &c. The application may be repeated on two or more days if the infestation is heavy. Fine combs are useful in detecting and removing vermin from the head. Tobacco extract has been advocated failing other available remedies. In the case of P. vestimenti, the lice can be killed as follows: Under-clothes may be scalded—say, once in ten days. Turn coats, waistcoats, trousers, &c., inside out; examine beneath the folds at the seams and expose these places to as much heat as can be borne before a fire, against a boiler, or allow a jet of steam from a kettle or boiler to travel along the seams. The clothing will soon dry. If available, a hot flat-iron, or any piece of heated metal, may be used to kill vermin in clothing. Petrol or paraffin will also kill nits and lice in clothing. If no other means are available, turn the clothing inside out, beat it vigorously, remove and kill the vermin by hand—this will, at any rate, mitigate the evil.

6. As far as possible avoid scratching the irritated part.

7. Privates would benefit by instruction in these matters.

8. Apart from the physical discomfort and loss of sleep caused by the attacks of lice, it should be noted that they have been shown to be the carriers of typhus and relapsing fever from infected to healthy persons. Typhus, especially, has played havoc in the past, and has been a dread accompaniment of war.

Dr. R. F. Drummond has drawn my attention to a common folklore belief emplanted in the minds of our poorer people. Incredible as it seems, these uneducated and ignorant folk believe that lice on the person is a sign of productivity, and that should they be removed their hosts will become barren or sterile. They transfer, by a process of sympathetic magic, the productivity of the lice to the lousy. As Dr. Drummond writes, these ignorant mothers and aunts believe that the nits and the lice arise spontaneously, and are ‘an outward and visible sign of an inward and invisible fertility.’ Those who try to cleanse the heads and the bodies of our primary schoolchildren are ‘up against’ the superstitions of the little ones’ guardians, and the guardians unfortunately often prove the stronger. Similar views are held widely by the various peoples of India and the East—people we call heathen—and, apart from the connexion thought to be established between fertility and lice, the presence of the latter is considered both at home and abroad to be a sign of robust health.

The rather obscure connexion of the louse and the pike (Esox lucius) is probably due to the fact that the Latin name for the pike is Lucius. The poor pun in ‘The Merry Wives of Windsor’ on the Lucy family is due to a similar resemblance in sound.

The Editor of the Morning Post has given me leave to quote the following paragraphs from an article by his able Correspondent at Petrograd.

All armies, after a few weeks’ campaigning, whatever other hardships may come their way, are sure of one—namely, certain parasites. Even officers under most favourable conditions are unable to keep clear of this scourge. Silk under-clothing is some palliative, but no real preventative. Various measures have been proposed to relieve the intense annoyance caused by millions of parasites of at least two species. Flowers of sulphur, worn in bags round the neck, were supposed to be a preventative, but proved fallacious.[1] What seems likely to prove perfect prophylactery is recommended by M. Agronom, who writes from Bokhara, where he has noted the habits of the Sarts and their preventative measures.

The Sarts never wash, and hardly ever in lifetime change their clothes; therefore their condition would be impossible without some preventative measures. They take a small quantity of mercury, which they bray into an amalgam with a plant used in the East for dyeing the hair and nails—probably henna. This paste is evenly laid on strands of flax or other fibres. One string thus prepared is worn round the neck and the other round the waist next the skin, the heat of the body producing exhalations which kill parasites. The string lasts quite a long time.

M. Agronom has made experiments with the ordinary mercurial ointment prepared with any kind of fat, and finds the effect precisely the same. He asserts that such a minute quantity of mercury as is required to produce the desired result is perfectly harmless to the system. A half-crown’s worth of mercury brayed in a mortar with lard or other fat will suffice to treat enough threads for several hundred soldiers. The threads should be of ten or a dozen strands or some very loosely twisted material like worsted, and should be wrapped in parchment paper before boxing for dispatch to the soldiers. This is effective and lasting for body parasites. Others are easily dealt with by rubbing in petroleum, which must be done twice at a week’s interval.

It should also be noted that no ordinary washing methods will clear the parasites from body-linen even when dipped in boiling water; but if a couple of spoonfuls of petroleum are added to every gallon of water, perfect success is assured even without boiling.

I confess I think he is a little bit too dogmatic about the habits of the Sarts. I am told the better-class Sarts do occasionally bathe, or why are there public baths at Khiva? After all, in our oldest and most cultured University, only a year ago, the venerable Head of a House exclaimed with some acerbity, when a junior Fellow suggested putting up hot-water baths for the undergraduates: ‘Baths! why the young men are only up eight weeks!’

And, again, though the clothes of the Sarts are doubtless flowing, unless they are elastic, they must get bigger as babyhood passes to boyhood and boyhood passes to manhood.

Preparations of mercury are also used in India: not only against human lice, but against the Mallophaga or biting-lice which infest the Indian birds used in falconry. It is difficult for a zoologist to believe the last paragraph of the Morning Post correspondent. The temperature of boiling water coagulates animal protoplasm as it does that of the white-of-egg; and what would the lice do then, poor things?

Early in the year, Mr. C. P. Lounsbury, the well-known Government Entomologist in South Africa, wrote that they were supplying the troops there with sulphur-bags which were supposed to keep the lice away. The sulphur is put in small bags of thin calico, and several of these are secured on the under-clothing, next to the skin. The bags are about two inches square, and I am told that it is customary to have one worn on the trunk of the body and one against each of the nether limbs. Whether this is effective will probably be known soon; but that flowers of sulphur do play an effective part in keeping down these troubles is shown by a letter of Dr. Harding H. Tomkins:—

Over thirty years ago, when house-surgeon at the Children’s Infirmary, Liverpool, I used this with absolute success in all cases of plaster-of-Paris jackets who formerly had been much distressed by vermin getting under the jacket. The sulphur was rubbed well into the under-clothes.

But still more interesting evidence is given by Dr. N. Bishop Harman:—

When I was serving in the South African War, and attached to No. 2 General Hospital at Pretoria, I was detailed to take medical charge of the camp of released prisoners that was established a few miles out of the town on the Delagoa Bay railway line. I moved into the camp the night they came in. Next day an inspection was held. I do not think I ever saw such a sorry sight. The men were in the most nondescript garments, and they were flabby from the effects of the food the Boers had given them—mealy pap, for the most part. They had had no washing facilities, and they were dirty in the extreme. Amongst them were a number of men of the D.C.O. Yeomanry, many of them Cambridge men, and when these came to me for special examination, unwarily I invited them into my tent to strip, and their clothes were laid on the only available support—my bed. The next day or two was spent in cleaning up the men and refitting them. By the end of the week I noticed in the evening an unpleasant itch about the lower part of the trunk: a sub-acute sort of itch, it did not seem like a flea, and I could find nothing. But after a most diligent search with all the candles I could borrow, I found, to my horror, a louse. It was a genuine body-louse. Then I remembered my folly in inviting strangers into my tent. Water was scarce, the morning tub was only the splash from a can. Laundry was impossible. But after some trouble I managed to get a can of hot water and get some sort of a hot wash. My man did the best he could with my shirt and pants. What to do with the bedding—dark brown blankets—I did not know, except to expose them to the hot sunshine. I rode into the town, but insect-powder could not be got. It came into my mind that I had read or heard that people who took sulphur-tablets smelled of H2S, so on the chance that an outside application might be of some service I got a supply of flowers of sulphur. This I liberally sprinkled all over my clothes, bedding, and rubbed into the seams of my tunic and riding-breeches. The itching was stopped in a day, and it never came again. But I soon noticed another circumstance: all the bright brass buttons of my tunic, although freshly polished by my man every morning, were tarnished before evening, even in the clean, dry atmosphere of the dry veld. Also my silver watch-case went black. There was no doubt that the sulphur was acted upon by the secretions of the skin and H2S was produced, and this I had no doubt killed off any lice that could not be got at by washing. Subsequently, I always used it when I was in likely places. And some places were very likely! In Cape Town, I had to inspect all the soldiers’ lodgings in view of the spread of the plague. And, again, I had charge of a Boer prison-ship, and never once did I catch so much as a hopper. The prison-ship was literally alive with cockroaches of all sizes; our cabins swarmed with them, but they avoided my clothes and kit like a plague, and there was never a nibble-mark to be found. I gave the hint to many men and they confirmed my experience. I have since met other men who hit on the same device with equal success. In this war I have told the tip to many friends, and some relatives, who have gone out, and so far they have been free from the plague. You will note that I used all the other measures I could, but my bedding and uniform were not washed, and the lice must have come through the bedding; there was no other possible means I could trace. Yet the flowers of sulphur killed off all that might be therein.

A very effective method for exterminating vermin in infected troops was carried out by Dr. S. Monckton Copeman, F.R.S., at Crowborough. To put the matter briefly, I append a copy of his able and concise memorandum which was distributed to all the medical officers of the Division; but further details may be obtained by referring to the British Medical Journal, or the Lancet of February 6, 1915.

To the Medical Officer....

Treatment for Destruction of Vermin.

Arrangements should be made for the bathing of affected individuals and other inmates of infected tents.

After drying themselves, men to lather their bodies with cresol-soap solution (water 10 galls., Jeyes’ fluid 1½ oz., soft soap 1½ lb.), especially over hairy parts, and to allow the lather to dry on.

Shirts to be washed in cresol-soap solution made with boiling water.

Tunics and trousers to be turned inside out, and rubbed with same lather, especially along the seams. Lather to be allowed to dry on the garment.

The materials can be obtained from the A.S.C. on indent authorised by A.D.M.S. in the form attached.

Infected blankets were at first treated by soaking them in cresol-soap solution, after which they were sent to a neighbouring laundry to be washed—a small contract rate having previously arranged. In the first week in November, however, a portable Thresh’s steam disinfecting apparatus was supplied to the Division, through the Second Army, since when no difficulty has been experienced in the disinfection both of clothing and blankets.

As a matter of fact the simple and inexpensive method which has been employed by us over a period of several months has proved so successful that no necessity has arisen for a trial of any other means of treatment.

Professor Lefroy, of the Royal College of Science and Technology, recommends two effective remedies, known respectively as ‘Vermijelli’ and ‘Vermin Westropol.’[2] Lieut.-Colonel E. J. Cross has successfully treated the clothes and bedding of his men with a powder consisting of three parts of black hellebore root and one of borax, and many similar powders are produced by the manufacturers of insecticides.

Let us end up this chapter cheerfully!

The importance of lice is equalled by their unpopularity. A lady, driven to extremes by—well let us call it—the want of gallantry of Dr. Johnson, called him ‘a louse.’ The great lexicographer retorted, ‘People always talk of things that run in their heads!’