CHAPTER II

THE BED-BUG (Cimex lectularius)

In ‘x’ finita tria sunt animalia dira;

Sunt pulices fortes, cimices, culicumque cohortes;

Sed pulices saltu fugiunt, culicesque volatu,

Et cimices pravi nequeunt foetore necari.

(ANON.)

AMONG the numerous disagreeable features of the bed-bug is the fact that it has at least two scientific names—Cimex (under which name it was known to the classical writers) and Acanthia. The latter name is favoured by French and some German authorities, but Cimex was the name adopted by Linnaeus, and is mostly used by British writers, and will be used throughout this article. One cannot do better than take the advice of that wise old entomologist, Dr. David Sharp, and allow the name ‘Acanthia to fall into disuse.’

The species which is the best known in England is C. lectularius; but there is a second species which is much commoner in warm climates, C. rotundatus. As regards carrying disease, this latter species is even more dangerous than its more temperate relative. Other species, which rarely if ever attack man, are found in pigeon-houses and dove-cotes, martins’ nests, poultry-houses, and the homes of bats.

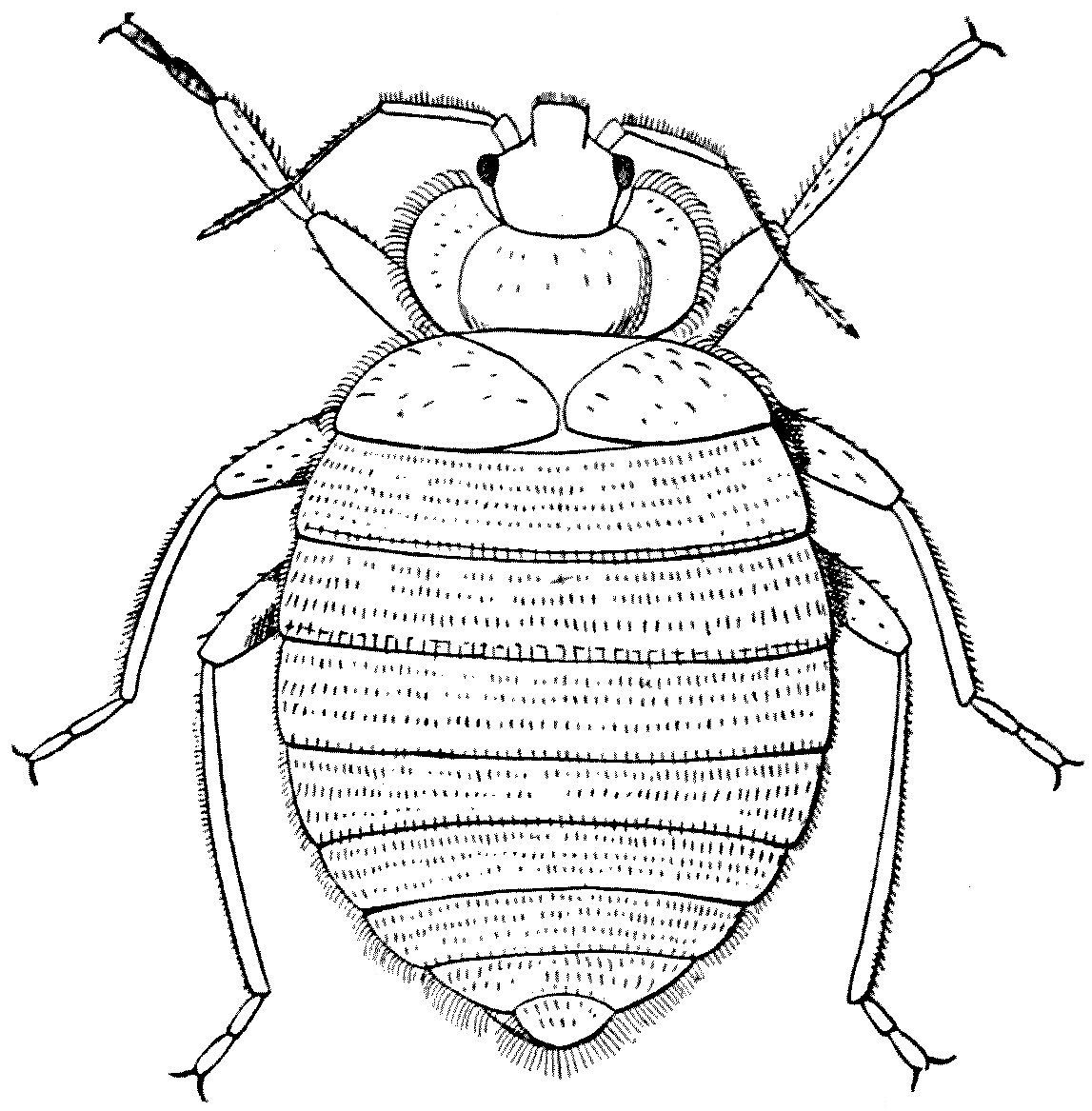

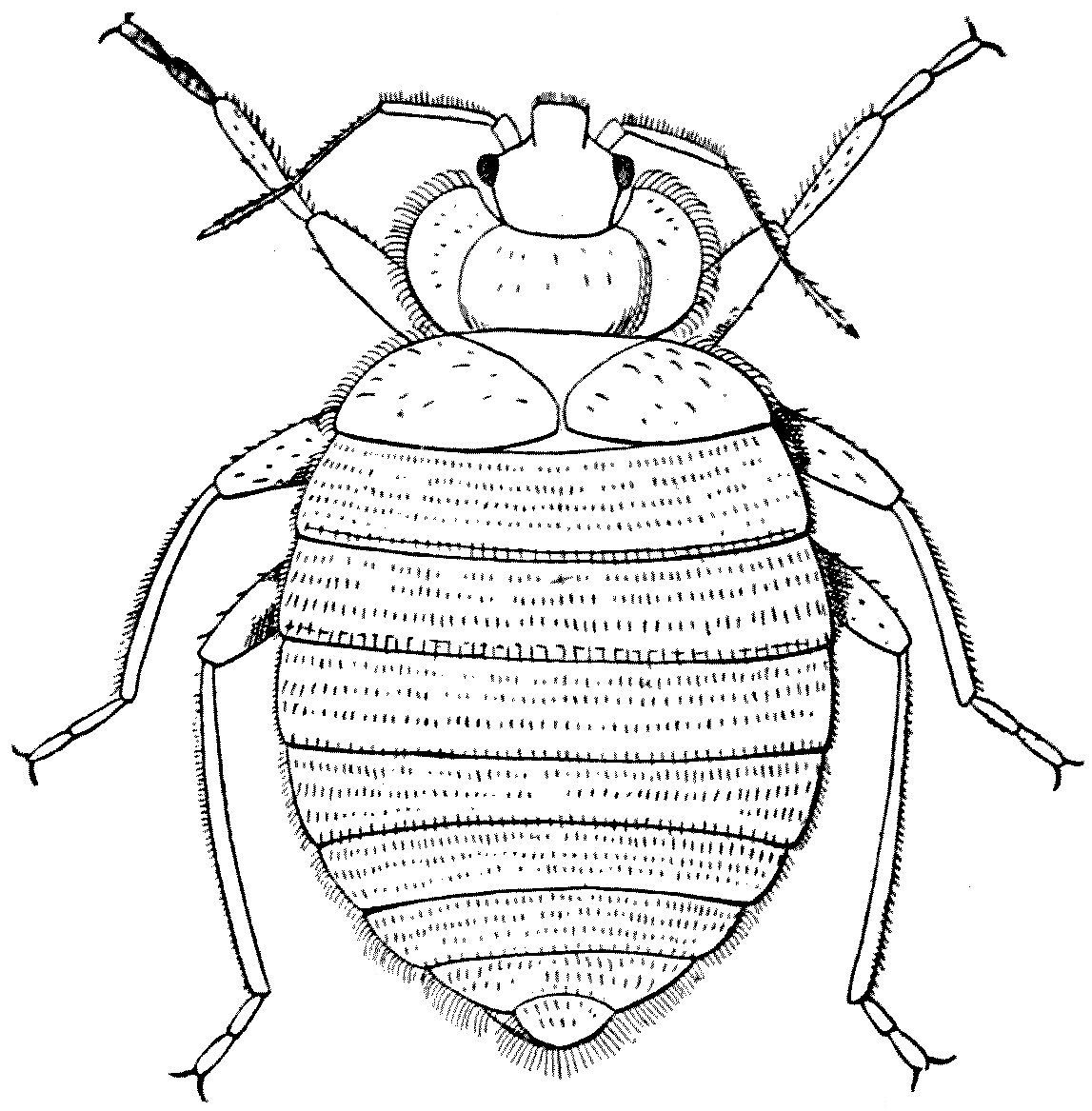

FIG. 3.—Cimex lectularius, male. × 15. (From Brumpt.)

The common bed-bug seems to have arrived in England about the same time as the cockroach—that is, over four hundred years ago, early in King Henry VIII’s reign. Apparently, it came from the East, and was for many years confined to seaports and harbours. It seems to have been first mentioned by playwriters towards the beginning of the seventeenth century. The sixteenth-century dramatists could never have resisted mentioning the bug had it been in their time a common household pest. It would have appealed to their sense of humour.

How the insect got the name of ‘bug’ is unknown. It has been suggested that the Old English word ‘bug,’ meaning a ghost or phantom which walked by night, has been transferred to Cimex. This may be so, but the ‘Oxford English Dictionary’ tells us that proof is lacking.

The insect is some 5 mm. in length and about 3 mm. in breadth, and is of a reddish- or brownish-rusty colour, fading into black. Its body is extraordinarily flattened, so that it can readily pass into chinks or between splits in furniture and boarding, and this it does whenever daylight appears, for the bug loves darkness rather than light. The head is large, and ends in a long, piercing, four-jointed proboscis, which forms a tube with four piercing stylets in it. As a rule the proboscis is folded back into a groove, which reaches to the first pair of legs on the under surface of the thorax. This folding back of the proboscis gives the insect a demure and even a devout expression: it appears to be engaged in prayer, but a bug never prays. The head bears two black eyes and two four-jointed antennae. Each of the six legs is provided with two claws, and all the body is covered with fairly numerous hairs. The abdomen shows seven visible segments and a terminal piece.

The bug has no fixed period of the year for breeding; as long as the temperature is favourable and the food abundant, generation will succeed generation without pause. Should, however, the weather turn cold the insects become numbed and their vitality and power of reproduction are interrupted until a sufficient degree of warmth returns.

Like the cockroach, the bed-bug is a frequenter of human habitations, but only of such as have reached a certain stage of comfort. It is said to be comparatively rare in the homes of savages, but it is only too common in the poorer quarters of our great cities. Its presence does not necessarily indicate neglect or want of cleanliness. It is apt to get into trunks and luggage, and in this way may be conveyed even into the best-kept homes. It is also very migratory and will pass readily from one house to another, and when an infested dwelling is vacated these insects usually leave it for better company and better quarters. Their food-supply being withdrawn, they make their way along gutters, water-pipes, &c., into adjoining and inhabited houses. Cimex is particularly common in ships—especially emigrant ships—and, although unknown to the aboriginal Indians of North America, it probably entered that continent with the ‘best families’ in the Mayflower.

Perhaps the most disagreeable feature of the bed-bug is that it produces an oily fluid which has a quite intolerable odour; the glands secreting this fluid are situated in various parts of the body. The presence of such glands in free-living Hemipterous insects is undoubtedly a protection—birds will not touch them. One, however, fails to see the use of this property in the bed-bug. At any rate, it does not deter cockroaches and ants, as well as other insects, from devouring the Cimex. There is a small black ant in Portugal which is said to clear a house of these pests in a few days, but one cannot always command the services of this small black ant.

Another remarkable feature is that the insect has no wings, although in all probability its ancestors possessed these useful appendages. As the American poet says:—

The Lightning-bug has wings of gold,

The June-bug wings of flame,

The Bed-bug has no wings at all,

But it gets there all the same!

The power of ‘getting there’ is truly remarkable. Man, their chief victim, has always warred against bugs, yet, like the poor, bugs ‘are always with us.’ I heard it stated, when I was living in southern Italy, that if you submerged the legs of your bed in metal saucers full of water and placed the bed in the centre of the room, the bugs will crawl up the wall, walk along the ceiling and drop on to the bed and on to you. Anyhow, whether this be so or not, there is no doubt that these insects have a certain success in the struggle for life, and only the most systematic and rigorous measures are capable of ridding a dwelling of their presence.

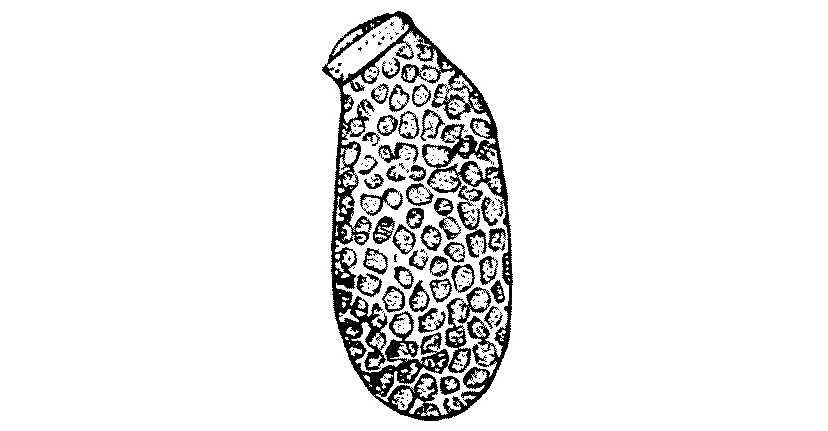

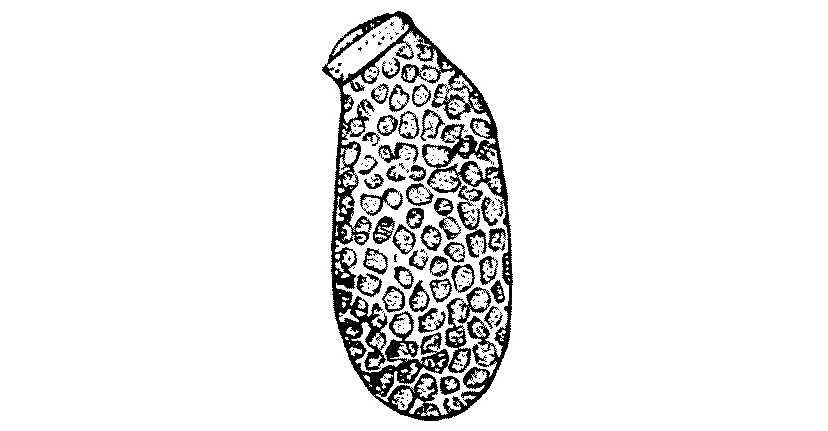

FIG. 4.—Egg of Cimex lectularius. Enlarged. (After Marlatt.)

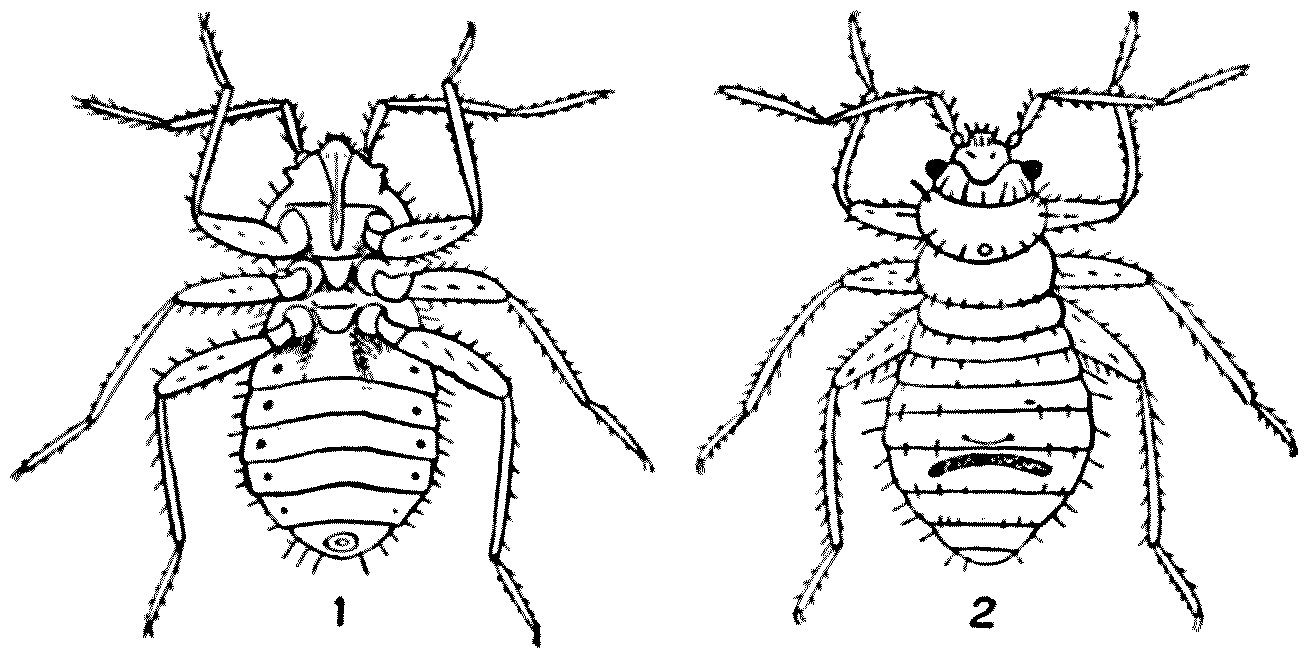

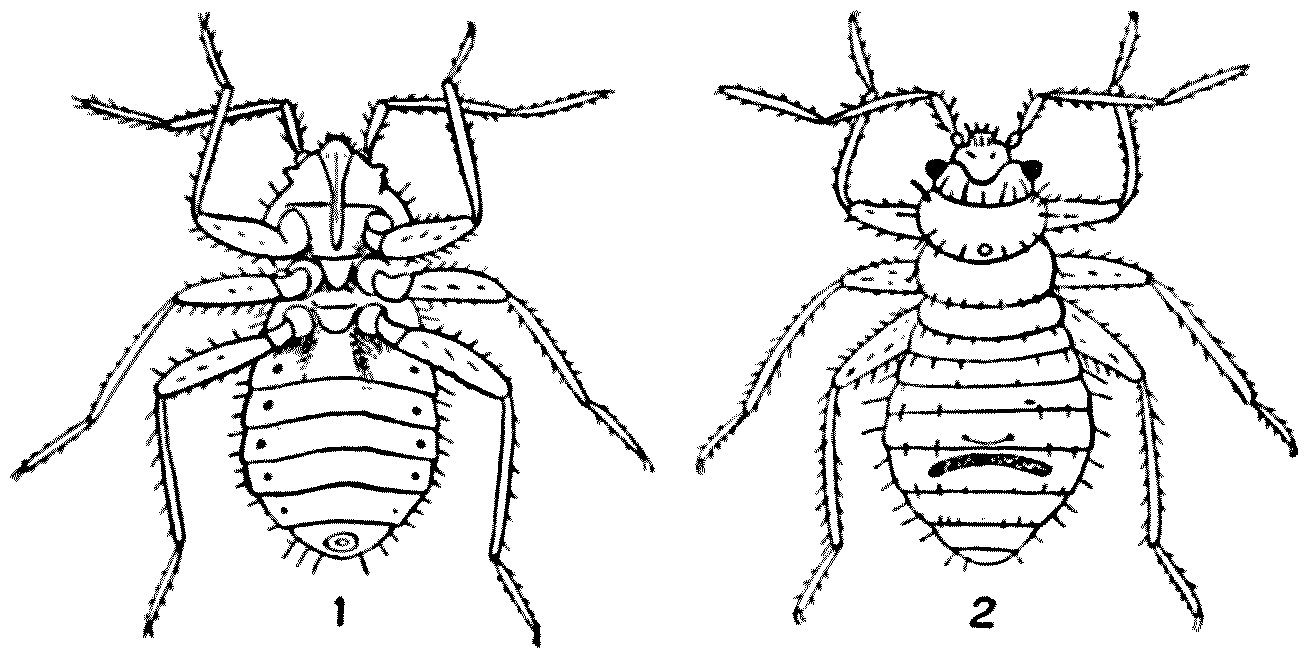

The eggs of the bed-bug are pearly white, oval objects, perhaps 1 mm. in length. At one end there is a small cap surrounded by a projecting rim, and it is by pushing off this cap, and through the orifice thus opened, that the young bug makes its way into the outer world after an incubation period of a week or ten days. There is no metamorphosis—no caterpillar and no chrysalis stages. The young hatch out, in structure miniatures of their parents, but in colour they are yellowish-white and nearly transparent. The young feed readily, and feeding takes place between each moult, and the moults are five in number, before the adult imago emerges. This it does about the eleventh or twelfth week after hatching. These time-limits depend, however, upon the temperature after hatching, and the rate of growth depends not only upon the temperature but also upon the amount of food.

When bred artificially and under good conditions, the rate of progress can be ‘speeded up’ so that the eggs hatch out in eight days, and every following moult takes place at intervals of eight days, so that the period from egg to adult can be run through in as short a time as seven weeks.

FIG. 5.—Newly hatched young of Cimex lectularius. 1, Ventral view; 2, dorsal view. Enlarged. (After Marlatt.)

Unless fed after each moult, the following moult is indefinitely postponed. Hence it follows that in the preliminary stages bugs must bite their hosts five times before the adult form emerges, and the adult must, further, have a meal before it lays its eggs. The eggs are deposited in batches of from five to fifty in cracks and crevices, into which the insects have retired for concealment.

Bugs can, however, live a very long time without a meal. Cases are recorded in which they have been kept alive for more than a year incarcerated in a pill-box. When the pill-box was ultimately opened, the bugs appeared to be as thin as oiled paper and almost so transparent that you could read The Times[3] through them; but even under these conditions they had managed to produce offspring. De Geer kept several alive in a sealed bottle for more than a year. This power of existing without food may explain the fact that vacated houses occasionally swarm with bugs even when there have been no human beings in the neighbourhood for many months.

The effect of their bite varies in different people. As a rule, the actual bite lasts for two or three minutes before the insect is gorged, and at first it is painless. But very soon the bitten area begins to swell and to become red, and at times a regular eruption ensues. The irritation may be allayed by washing with menthol or ammonia. Some people seem immune to the irritation; and I know friends who, in the West Indian Islands, have slept through the attacks of thousands of bugs, and only awoke to their presence when in the morning they found their night-clothing and their sheets red with blood, expressed from the bodies of their tormentors as the victims turned from side to side.

As a rule, the uncovered parts of the body—the face, the neck, and the hands—are said to be more bitten than the parts which are covered by the bedclothes. This is not, however, my experience.

The bug has been accused of conveying many diseases—typhus, tuberculosis, plague, and a form of recurrent fever produced by a spirochaete (Spirochaeta obermeieri); but a critical examination throws some doubt upon the justice of the accusation, and Professor C. J. Martin writes as follows:—

There is really no evidence to incriminate the bed-bug in the case of either typhus or relapsing fever. It is possible to transmit plague experimentally by means of bugs, but there is no epidemiological reason for supposing this takes place to any extent in nature.

There are two differences in the habits of bugs and those of fleas and lice which may possess epidemiological significance. The first concerns the customary intervals between their meals. Bugs show no disposition to feed for a day or two after a full meal, whereas fleas and lice will suck blood several times during the twenty-four hours. The second is in respect to the time the insects retain a meal and the extent to which it is digested before being excreted. Fleas and lice, if constantly fed, freely empty their alimentary canals, and the nature of their faeces indicates that the blood has undergone but little digestion.

Both these insects evacuate such undigested or half-digested blood per rectum during the act of feeding, and the remnants of the previous meal are thus deposited in the immediate vicinity of a fresh puncture. It is not unlikely that, should the alimentary canal of the insect be infected with plague bacilli, spirochaete, or the organism responsible for typhus fever, these may be inoculated by rubbing or scratching. Bugs have not this habit; and in all the cases I have examined their dejections were fully digested, almost free from protein, and consisted mostly of alkaline haematin.

Whether bugs be guilty of these crimes or not, they are the cause of an intense inconvenience and disgust, and should, if possible, be dealt with drastically. At the present time[4] there are rumours that some of our largest camps are infested with these insects, and there seems no doubt that some of the prisoners and refugees to this country have brought their fauna with them, and this fauna is very capable of spreading in concentration camps. The erection of wooden huts—no doubt a pressing necessity—will afford convenient quarters for these pests.

Among the measures which have been most successful in the past has been fumigating houses with hydrocyanic-acid gas; but this is a process involving considerable danger, and should only be carried out by competent people under the most rigorous conditions. In all fumigating experiments every crack and cranny of a house should be shut, windows closed, keyholes blocked, and so on. A second method of fumigation is that of burning sulphur. Four ounces of brimstone are set alight in a saucer, this in its turn is placed in a larger vessel, which protects the floor of the room from a possible overflow of the burning material. After all apertures have been successfully plugged, four or five hours of the sulphurous fumes are said to be sufficient to kill the bugs, but to ensure complete success a longer time is needed. This is not only a much less expensive but a much less dangerous operation than using hydrocyanic-acid gas. Two pounds of sulphur will suffice for each thousand cubic feet of space, but it is well to leave the building closed for some twenty-four hours after the fumigation. Another more localised method of destroying these pests is the liberal application of benzine, kerosene, or any other petroleum oil. These must be introduced into all crevices or cracks by small brushes or feathers, or injected with syringes. In the same way oil of turpentine or corrosive-sublimate has proved effective. Boiling water is also very fatal when it can be used; and recently in the poorer quarters of London the ‘flares’ which painters use in burning off paint have proved of great use in ridding matchboarding, or wainscoting, from the harbouring bugs. Passed quickly along, the flame of the ‘flare’ does not burn the wood, but it produces a temperature which is fatal to the bug and to its young and to its eggs. And thus:—

‘This painted child of dirt, that stinks and stings’[5] is destroyed.