Chapter Eleven

THE SOUL THAT ENDURES

ON an evening of late September Venice revealed herself to one of her lovers amidst a spectacle beyond any range of dreams. Evening was closing in upon the city with cloud and breeze. In the church of San Giorgio Maggiore the Tintorettos gleamed dimly from the walls; daylight was gone. But in the tower high overhead, clear of the shadows of confining buildings, the day had still a course to run. The tide was low, and land and water stretched out in interchanging coils of olive and azure beneath a purple storm-cloud, whilst ever against the bar of the Lido rolled the sea, dyed with that celestial blue that sometimes steals from the Adriatic into the basin of San Marco to prostrate itself at the conquering Lion’s feet. And there lay Venice, her form outlined against a flood of pearl, the water bending in a tender, luminous bow behind her towers. Far away, across the mysterious expanse of low lagoon, Torcello and Burano gleamed out in startling pallor against the storm, amid a wild confusion of dark earth and glittering water. The Northern Alps were hidden in darkness at the horizon, but westward across the mainland the clear, sharp peaks of the Euganean hills rose up behind the city’s pearly halo, behind the deep blue of the surging lowlands, in almost unearthly outline against the sunset sky. In front of them a livid fire rolled sullenly along the valley, sending up purple smoke into the cloud. The storm genie, summoned by nether powers, was descending to his fearful tryst behind the Euganeans, but, as he sank, he bent his face upon the pale form of Venice, his enchantress, and the fire of his wonder and of his adoration kindled in all her slumbering limbs a glow of responsive life. A flood of crimson suffused the pallor of her pearly diadem, and her maidens, sleeping grey among the waters round her, unfolded rosy petals upon the surface of the lagoon.

It is this power of living communion with the daily pageant in which sun and moon are doge and emperor, and the stars and the clouds their retinue—this it is which, finding expression once at Venice in a temporal glory that has passed away, is the abiding assurance of her immortality. This is the spirit which, if once it helped to make her great, still makes her great to-day, the spirit that endures. For Venice is not a dead body: she is a living soul. Overflowing all moulds in which we may think to contain her, she reveals herself continually in new mystery, new wonder. We spoke of Venice as being paved with sky, and every day there is cast upon her pavement a fresh revelation of changefulness and beauty. A thousand forms and patterns move in procession over the water, passing each instant into something “rich and strange,” a fleeting succession of aerial designs drawn with tremulous pencil in colours which never lived on the palette of a mortal artist. There is a body of truth at the root of the old fancy which gifted water-maidens with subtler, more perilously powerful allurements than their sisters of the land. Their element is mutability, but they are not soulless, as men have said: it is only that their soul is as the soul of water—luminous, flowing, mutable, reflective, musical, profound: for, though they are mutable, they are not shallow; it is a part of their being that they should be susceptible of change. They cannot tire their victims, they whose beauty is continually renewed; and yet it may be that men do well to fear them, for they have secret communings with things men do not dream of. Venice has held men, she holds them still, with the fascination of a water spirit; they yield to her, they grasp her, but she is still before them, never mastered, never fully known. Let those for whom conquest is the ideal in love beware of Venice the incomparable, the uncompassable: they who would win her must have power to worship what they cannot comprehend, they must desire to leave her spirit free. Then she will unfold her heart to them, she will give herself in a moment when the pursuit is still. And to those who can receive the gift, she will give herself again and yet again; only they must come freshly expectant of each fresh revelation, not clinging to past impressions, not claiming a memory to be revived. For each renewal is a transformation, and we must bring new senses to receive it, senses alive and fresh as earth each morning to the touch of the old sun ever new.

Venice, when she was most glorious, did but catch and imprison in her stones those matchless harmonies of fleeting colour which the sun still lavishes upon her waters. And there is a season of the year which, with sun and mist co-operating, hangs once again her pale walls with their ancient splendour, and plays a noble part in the revival of the past. With the first days of autumn the scirocco begins to wind about the heart of her plants and creepers, and to steal into their veins. Swiftly they yield to the intoxication. Under the folds of the grey mist-mantle, they drink draught after draught of her brave wine. But another touch is needed to draw out the virtues of that liquor: after Circe, Apollo. He bends his look upon them, and they yield their stores, decking once more the walls of Venice with frescoes of scarlet, green and gold, paving once more her waterways with their old-accustomed pomp. In the Sacca della Misericordia this natural fresco has a peculiarly beautiful effect; for upon the spaces of water between the rafts that float there, the rich creepers, interwoven among the trees of the garden of the Spiriti, fling an enchanted carpet of chequered crimson and green upon a pale rose ground, covering the whole expanse, save for one space whereon is set the pale blue watermark of the sky. One may make rare studies here of the carpets and bright mats that are to be seen hung out in the pictures of the old Venetian masters. They did not copy from the East alone, or rather they copied from a greater East, whose treasures travel through a rarer element than water day after day to the shores of the western world. The complete stillness of the pools in the Sacca, undisturbed by any passing steamboat, and even unruffled by the motion of a gondola, through the protection of the intervening rafts, gives the rich pattern a durability unattainable in the waters of the canals. There is only, as it were, a faint breathing of the surface, enough to give perpetual interchange and commerce among the bold brush-strokes of colour—incessant, subtle weaving of new harmonies upon the ground-bass—the shadows deepening or relaxing, when sometimes an insect dips or a fish rises and starts a fairy circle at a touch that spreads among the colours until its delicate life is lost.

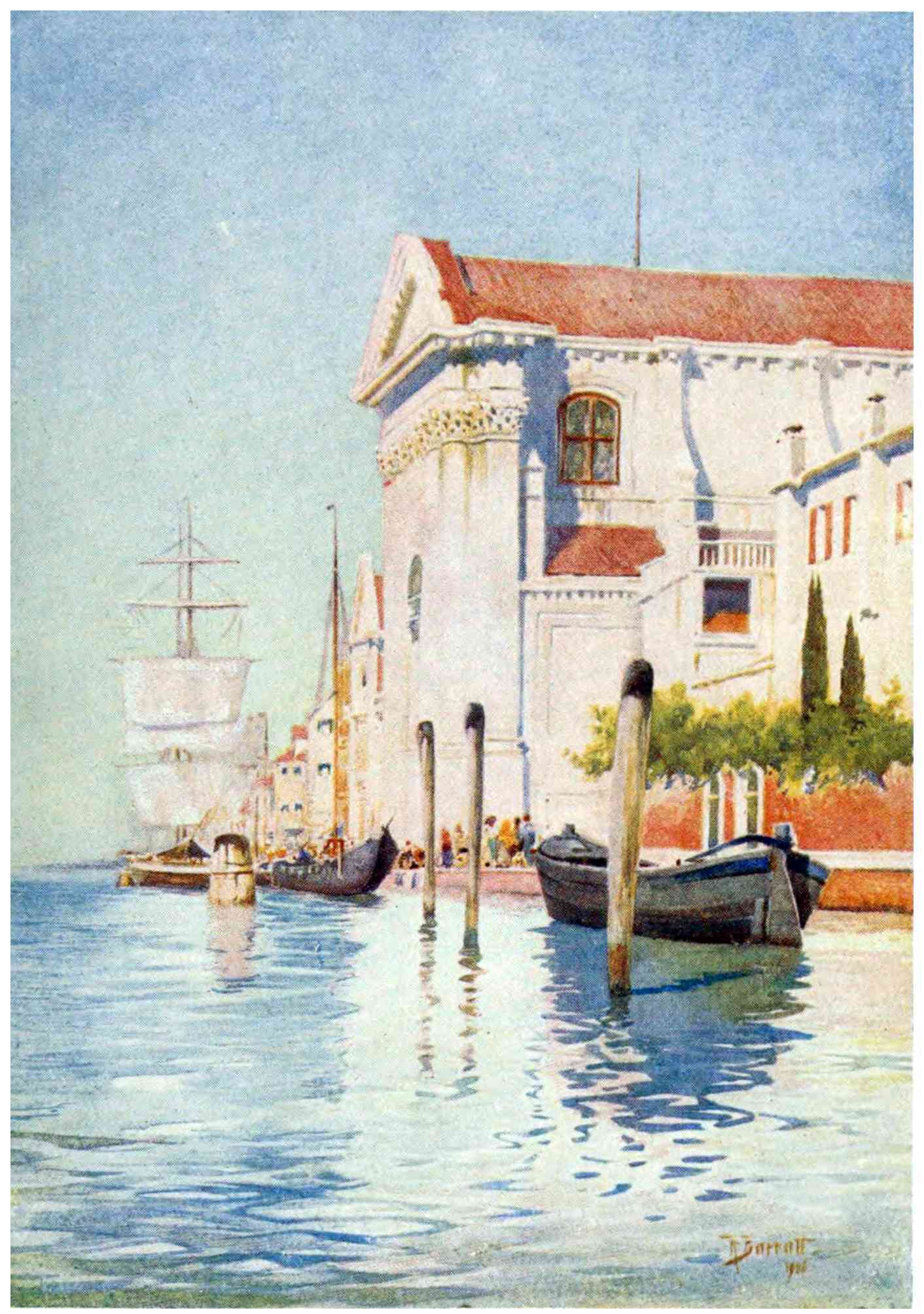

A PALACE DOOR.

And if at times we may thus see the past in the present, at other times we may dream the present back into the past. Night, the worker of so many miracles, holds a key with which we may unlock in Venice the secret of bygone times. There are hours on the lagoons when even in daylight the forgotten ages live again and we may keep company with whom we will, but in the heart of the city it is by night that we may lay hand on the pulse of her ancient life, and feel it warm to our touch, beating slow but constant behind the commotion, often the desecration, of later times. The flow of the Grand Canal is less troubled than by day: it has intervals of peace in which it may sink into the broad, dark calm of Carpaccio’s waters. Palace after palace, in fearless and unstudied alternations of Byzantine, Gothic, Ogival, Renaissance, Barocco, tower above us, their pillars and balconies gleaming in faint light of moon or lamp: we seem almost to trace upon their surface the forms of men and beasts, and to clothe them once more in the gold and colour which Venice learned of her lagoons. By day we feast upon the tints still left to fall upon the waters, we praise the aged snow of crumbling stone or the shades of twisted columns, or the rich profusion of the pale Cà d’Oro. But what do we know of Venice when she shone upon the waters in true regality, a monument of all the glory that the heart or eye of man could conceive? No one has left us any detailed record of the frescoed façades of the Venetian palaces, whether on the Grand Canal or in the remoter waterways; only here and there we catch a glimpse of them on the canvases of contemporary painters. It is provokingly general among the travellers or native-lovers of Venice, who set themselves to praise her in words, to find that they have chosen a medium incapable of achieving what it was asked to do, and to throw down their weapon in the moment of trial, struck dumb by the immense wonder of their theme. They cease from their task before, it seems to us, they have well begun it, always anticipating the stinging tongue of the dragon, Incredulity. We could well forgive them their inadequacy, so frankly recognised, had they but attempted a mere catalogue of some of the frescoes on the walls. Now, it is at night alone that we can repeople them; that, as we pass along, we can look up and read into the shadowy spaces those brilliant chronicles of beauty, power and pride. It is, indeed, a heavy fate that awaits in Venice the artist who must work in words; colour and music can draw nearer, can almost attain to the reality itself; and yet by words also there is something to be conveyed of her enduring beauty. The fact which words can compass may be so told that there is born from it a sentiment of that rich atmosphere which is beyond the reach of words; they may remind or may awaken wonder, itself a new sense with which to apprehend. Even words may tell of the water snake of green and gold that writhes and gleams hour after hour in the faintly stirred depths of the canal, a creature that in the world above is a dull grey upright pole; or of golden treasures, once the refuse of the calli, transformed to splendour as they float out over the lagoon; or of the sudden lapping of the water under the wind down the north lagoon at midnight, that breaks the smooth image of the moon into a thousand ripples and passes in a wave that makes the dim lamps tremble into the narrow waterways of the city.

But it is not only the waterways of Venice that at night are eloquent of the past, that seem to take once more their ancient shape and venture near for colloquy: the streets and squares and churches are full of spirits, not unkindly, not afraid, less silent and secretive than in the busy day, when they are lonely among a people careless of them, with other thoughts, other needs and other destinies. Many a porch or gable or wide-projecting roof, or sculpture of fantastic beast or naïve saint or kneeling angel, seems to step out and call upon us in the night, catching in us perhaps as we pass by some touch of sympathy with the enduring soul of the past. One must be late indeed in Venice to secure untroubled peace. Ever and again, even after midnight, the silence of the great white campos is broken by a group scattered here and there before the door of a café; voices in eager talk will echo under a low portico, a sleepy child will clatter by in wooden pattens. But in the low-beamed, dimly lighted courts, or on the dark steps at the water-side, under some deserted sotto-portico, the sounds of the present strike across us like distant voices in a dream. The one night that lies over all the ages draws our spirit into harmony with these stones and lapping waters, that have stood through change and stress of time, that have outlived solemnity and joyous festival and have passed from gentle usage and glorious vesture into the custody of the poorest, into neglect and decay. What talk have not these courtyards overheard, what rich vesture has not swept through them, what noble thoughts and high hopes have not confided in their silence? And on the dirty steps where the children sit and play and throw their refuse into the water, what carpets have not been spread, what proud feet have not pressed to pass into the gondola and join the triumphant processional of Venice in her prime?

But what of ancient Venice? We sometimes despair of re-creating her. We ponder on Rialto, we watch her lights from the lagoons, we go in and out among her calli, peering into door and courtyard, climbing an outer stair, penetrating the recesses of sotto-portico or cellar; and many records we find of the life which once she lived, but all belong to the Venice of that second age, when she was already an established city. We cannot depopulate her and see again that company of islands gathered together in the lagoon, of various shapes and sizes, some covered with wood and undergrowth, others rising with bare backs from the water, with large and lonely outposts lying at greater distance here and there. Yet now and again come days when the spirit even of this remoter period returns to its well-nigh forgotten grave, the days when Venice lies under the rule of the rain-clouds. The inner waterways of the city lie dead like opaque marble under the dancing drops; but down the ways that lead from the lagoons the wind pours strong and restless from the sea, beating the water against the walls and into the damp vaults, a challenge from the sea to the city, from the sea unbridled and insurgent—yet not insurgent, for it has never submitted to her sway. Within Venice, along the slippery streets, there is gloom and desolation; the sun is the only visitor to whom her heart stands ever open; she would shut her gates if she could to these wild beings of cloud and wind, these houseless, grey pilgrims that, at no bidding of hers, come and claim lodging with her as they take their nomad way. I know not what of the old, wild fisher heart comes to visit Venice in these days; phantoms of old time are borne in on the gusty winds from the sea and the lagoon, and the commanding voice of the sea wind they must have known so well seems to clothe them with substantial life. Into the mist vanishes the frescoed Venice of high pomp and festival, the Venice of regal Bucintoro and banqueting of kings, of brilliant policy and stem civic control. A still deeper oblivion receives the Venice of small joys and small sorrows, of Longhi and Goldoni; and the excitement of the formless past creeps into us, when yet the future was to make—the hard life of the first dwellers upon the islands, acute and mobile in their hourly traffic with wind and sea.

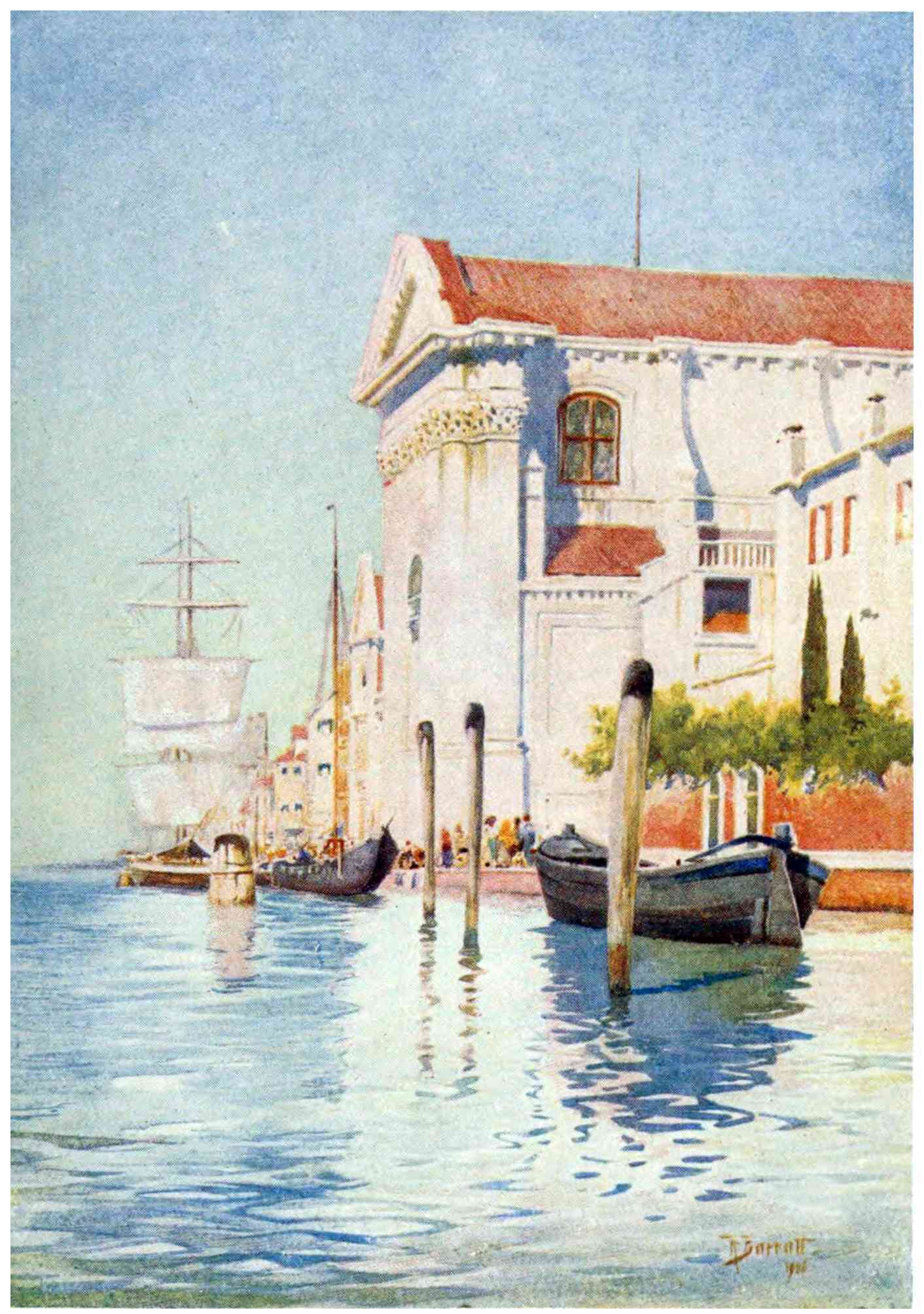

ZATTERE.

There is a corner of Venice little known to the stranger, or even to Venetians themselves, except as a passage to the cemetery of San Michele, but not less loved on that account by those who are happy enough to have their lot cast there. The breezes blow with a freshness that is rare in the more confined spaces of the city or on the Grand Canal; the tide sets into the Sacca della Misericordia full and fresh from the northern lagoon, still beating with the pulse of the open sea. This favoured, this unique corner of Venice is a large square basin of water, open on one side to the lagoon. Venice, at one time, could boast of many such, but one by one they have been filled in with earth, and in the sixteenth century, when the neighbouring Fondamente Nuove were built, the Sacca della Misericordia itself narrowly escaped inclusion in the paved parade that was to unite the whole of North Venice from Santa Giustina to Sant’ Alvise. The fiat had gone forth, but happily it remains as yet unfulfilled, and the Sacca is still a harbour for the zattere, the timber rafts that are brought down from the mountains, and set here to season awhile, in sight of their old home, till at last they are borne away to do service in the works of man. A tiny hut of planks without a door is set up here and there upon the rafts, and a couple of dogs are continually upon the prowl. Something in this woodyard, the building of the rafts, the lapping of the inflowing tide against them, its waves twisted in some angle into a petulant restlessness, seems to carry us back to the primeval days before the historic settlement of the fugitives from the great mainland cities, back to the manners of the humble fishermen who lived a hard and frugal life among the low islands of the Adriatic, in constant commerce with their patron the sea, in constant vigilance against his aggression.

The night-lapping of the waves against the Sacca della Misericordia calls to mind the two toiling fishermen of Theocritus, whose life must have been strangely like that of the first dwellers on the Rivo Alto. Let us quote from Mr. Andrew Lang’s translation. “Two fishers on a time together lay and slept: they had strown the dry sea-moss for a bed in their wattled cabin, and there they lay against the leafy wall. Beside them were strewn the instruments of their toilsome hands, the fishing-creels, the rods of reed, the hooks, the sails bedraggled with sea-spoil, the lines, the weels, the lobster-pots woven of rushes, the seines, two oars and an old coble upon props. Beneath their heads was a scanty matting, their clothes, their sailor’s caps. Here was all their toil, here all their wealth. The threshold had never a door, nor a watch-dog: all things, all to them seemed superfluity, for Poverty was their sentinel. They had no neighbour by them, but ever against their narrow cabin gently floated up the sea.” This is a page for the history of Venice in her infancy, or rather for the history of that earlier time when Venice was as yet unborn. Out among the islands of the lagoon, which on a calm, vague day of summer seem to hover in the atmosphere upon a silver haze, among those luminous paths of chrysophrase and porphyry, mother-of-pearl and opal, we shall still find some footsteps of these first Venetians unerased by tract of time.

Perhaps it is at Sant’ Erasmo that the print is clearest; there are few materials that we cannot find here for reconstruction of the primeval settlement. There are the rush-roofed shelters of the boats and the rude landing-stages; there are the low, white capane roofed with thatch or tiles, the long, narrow, stagnant waterways, the high, grassy levels bordering the water; there are fields of reeds, and thickets or fringes of rustling poplars; there are valli where the fish stir and leap and gleam continuously, breaking the smooth water into a thousand ripples; there is the broad, central waterway, and countless lesser channels and pools among the reeds, where one may see a boat slowly winding, guided perhaps by children, their little figures standing out against the desolate landscape, the silence broken by no voice but theirs. Thus must Venice have been in her infancy. And if from among these lonely waterways and grassy flats of Sant’ Erasmo we look forward into the future, we can anticipate the gradual evolution of a city such as Venice was afterwards to be. The building of the first mud-huts; the driving of the first close-set clumps of piles to support more solid structures; the filling of marsh-pools and strengthening of foundations; the light wooden bridges thrust across the water, as one may see them on the Lido to-day; the transition from houses of wood to houses of brick and stone, from thatch to tiles; the building of churches on the higher ground, each with its plot of grass about it; the paving of the most frequented ways, the construction of wells and chimneys, of paved campo and fondamenta; till we reach at last the city of palaces, of temples and of towers, the city of sumptuous and varied colour, the Venezia nobilissima of Carpaccio and Gentile Bellini.

END