VENICE

Chapter One

INTRODUCTORY

“VENICE herself is poetry, and creates a poet out of the dullest clay.” It was a poet who spoke, and his clay was instinct with the breath of genius. But it is true that Venice lends wings to duller clay; it has been her fate to make poets of many who were not so before—a responsibility that entails loss on her as well as gain.

She has lived—she has loved and suffered and created; and the echoes of her creation are with us still; the pulse of the life which once she knew continues to throb behind the loud and insistent present. The story of Venice has been often written; the Bride of the Adriatic, in her decay as in her youthful and her mature beauty, has been the beloved of many men. “Wo betide the wretch,” cries Landor through the mouth of Machiavelli, “who desecrates and humiliates her; she may fall, but she shall rise again.” Venice even then had passed her zenith; the path she had entered, though blazing with a glory which had not attended on her dawn of life, was yet a path of decline, the resplendent, dazzling path of the setting sun. And now a second Attilla, as Napoleon vaunted himself, has descended upon her. She has been desecrated, but she has never been dethroned. She could not, if she would, take the ring off her finger. No hand of man, however potent, can destroy that once consummated union, however the stranger and her traitor sons may abase her from within.

It is to her own domain, embraced by her mutable yet eternally faithful ocean-lover, that we must still go to see the relics of her pomp. The old sternness has passed from her face, that compelling sovereignty which gave her rank among the greatest potentates of the Middle Age; her features, portrayed by these latter days, are mellowed; a veil of golden haze softens the bold outlines of that imperious countenance. We are sometimes tempted to forget that the cup held by the enchanter, Venice, was filled once with no dream-inducing liquor, but with a strong potion to fire the nerves of heroes. Viewing Venice in her greater days, it is impossible to make that separation between the artist and the man of action so deadly to action and to art. The portraits of the Venetian masters, supreme among the portraits of the world, could only have been produced by men who beyond the divine perception of form and colour were endowed with a profound understanding and divination of human character. The pictures of Gentile Bellini, of Carpaccio, of Mansueti, are a gallery of portraits of stern, strong, capable, self-confident men; and Giovanni Bellini, who turned from secular themes to concentrate his energy on the portrayal of the Madonna and Child, endowed her with a strength and solemn pathos which only Giotto could rival, combined with a luminous richness of colour in which perhaps he has no rival at all.

No mystics have sprung from Venice. Her sons have been artists of life, not dreamers, though the sea, that great weaver of dreams, has been ever around them. Or rather it is truer to say that the dreamers of Venice have also been men of action; strong, capable and intensely practical. They have not turned their back on the practice of life; they have loved it in all its forms. Even when they speak through the medium of allegory, of symbols, the art of Carpaccio and of Tintoretto is a supreme record of the interests of the greatest Venetians in the actions of everything living in this wonderful world, and in particular—they are not ashamed to own it—in their supremely wonderful city of Venice. There are dreamers among those crowds of Carpaccio, of Gentile Bellini; but their hands can grasp the weapons and the tools of earth; their heads and hearts can wrestle with the problems and passions of earth. Compare them with the dreamers of Perugino’s school: you feel at once that a gulf lies between them; the fabric of their dream is of another substance. The great Venetians are giants; like the sea’s, their embrace is vast and powerful, endowed also with the gentleness of strength. The history of Venetian greatness in art, in politics, in theology, is the history of men who have accepted life and strenuously devoted themselves to mastering its laws. They were not iconoclasts, because they were not idolaters: the faculties of temperance and restraint are apparent in their very enthusiasms. Venice did not fall because she loved life too well, but because she had lost the secret of living. Pride became to her more beautiful than truth, and finally more worshipful than beauty.

Much has, with truth, been said about the destruction of Venice. Even in those who have not known her as she was, who in presence of her wealth remaining are unconscious of the greatness of her loss, there constantly stirs indignant sorrow at the childish wantonness of her inhabitants, which loves to destroy and asks only a newer and brighter plaything. But much persists that is indestructible; and though Venice has become a spectacle for strangers, for those who are her lovers the old spirit lingers still near the form it once so gloriously inhabited, wakened into being, perchance, by a motion, an echo, a light upon the waters, and once wakened never again lost or out of mind. Does not the silent swiftness of the Ten still haunt the sandolo of the water police, as it steals in the darkness with unlighted lamp under the shadow of larger craft moored beside the fondamenta, visible only when it crosses the path of a light from house or garden? It is in her water that Venice eternally lives; it is thus that we think always of her image—elusive, unfathomable, though plumbed so often by no novice hand. It is the wonder of Venice within her waters which justifies the renewal of the old attempt to reconstruct certain aspects of a career which has been a challenge to the world, a mystery on which it has never grown weary of speculating. And as the light falling from a new angle on familiar features may reveal some grace hidden heretofore in shadow or unobserved, so, perchance, the vision of Venice may be renewed or kindled through the medium of a new personality.

Venice is inexhaustible, and it is from her waters that her mine of wealth is drawn. They give her wings; without them she would be fettered like other cities of the land. But Venice with her waters is never dead. The sun may fall with cruel blankness on calle, piazza and fondamenta, but nothing can kill the water; it is always mobile, always alive. Imagine the thoroughfare of an inland city on such a day as is portrayed in Manet’s Grand Canal de Venise; heart and eye would curse the sunshine. But in the luminous truth of Manet’s picture, as in Venice herself, the heat quivers and lives. Above ground, blue sky beating down on blue canal, on the sleepy midday motion of the gondolas, on the brilliant blue of the striped gondola posts, which appear to stagger into the water; and under the surface, the secret of Venice, the region where reflections lurk, where the long wavering lines are carried on in the deep, cool, liquid life below. When Venice is weary, what should she do but dive into the water as all her children do? If we look down, when we can look up no longer, still she is there; a city more shadowy but not less real, her elements all dissolved that at our pleasure we may build them again;

And so not build at all,

And therefore build for ever.

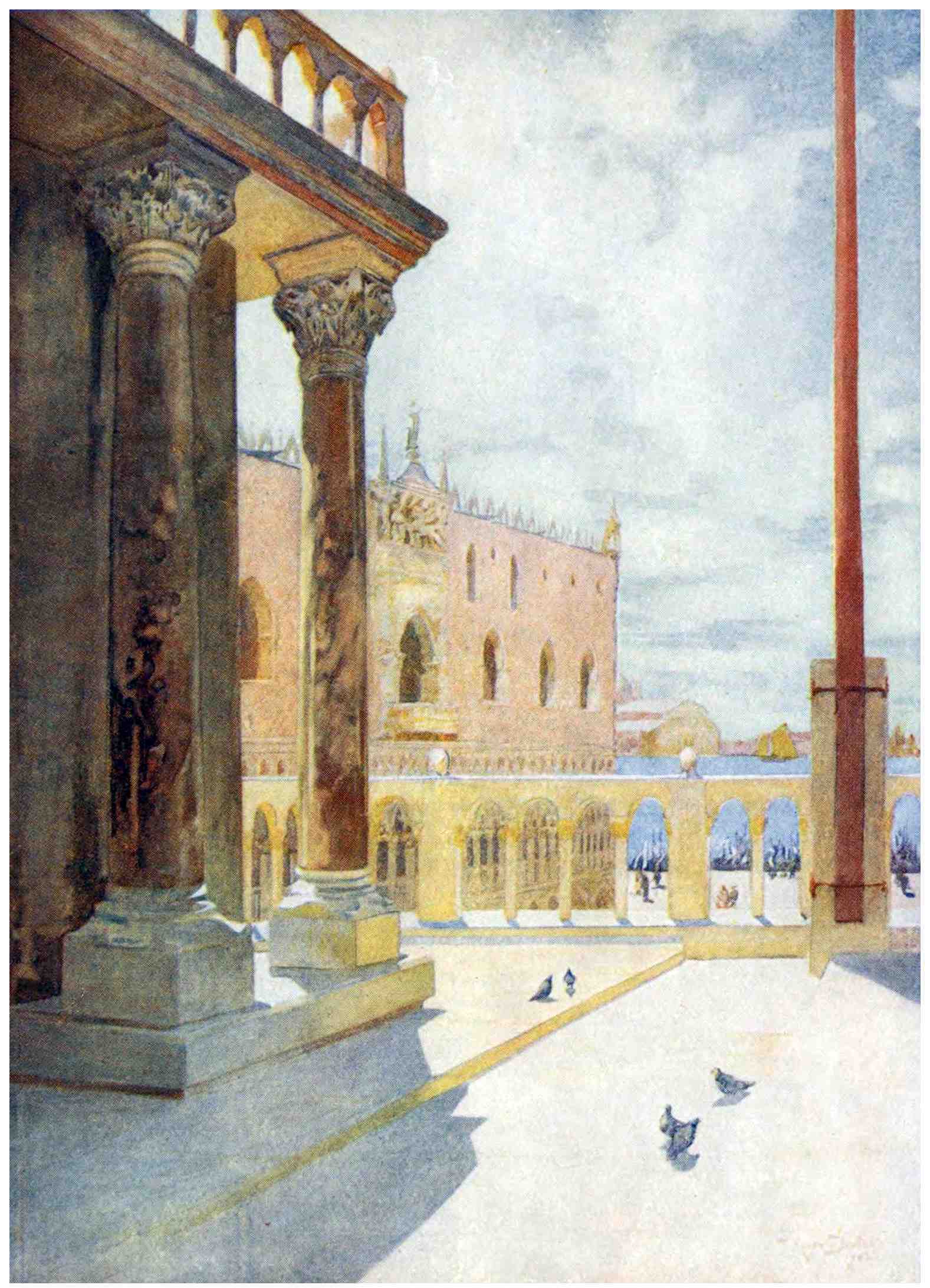

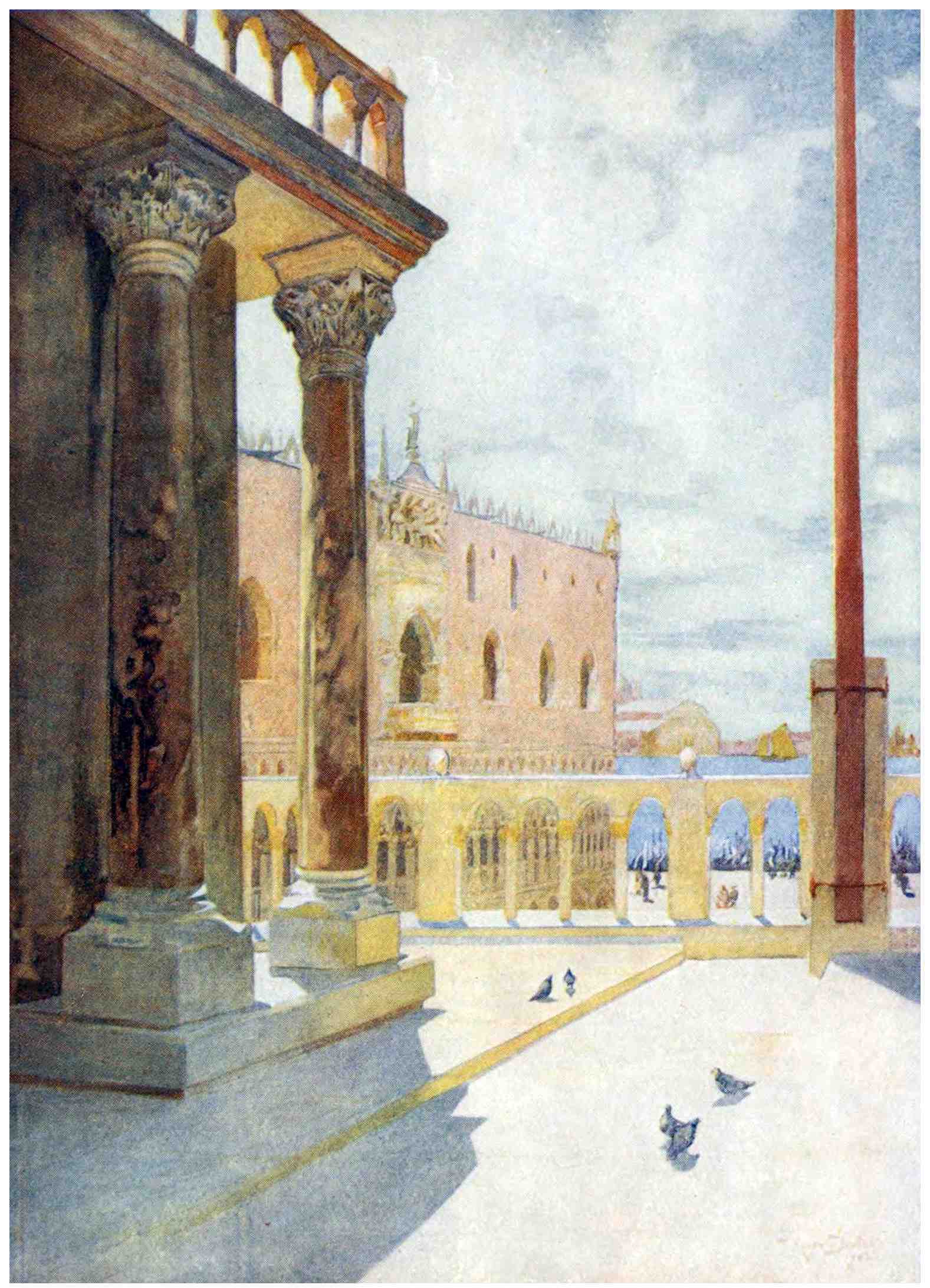

VIEW FROM THE GALLERY OF SAN MARCO.

And if in the middle day we realise this priceless dowry of Venice, it is in the twilight of morning or evening that her treasury is unlocked and she invites us to enter. Turner’s Approach to Venice is a vision, a dream, but not more divinely lovely than the reality of Venice in these hours, even as she appears to duller eyes. Pass down the Grand Canal in the twilight of an August evening, the full moon already high and pouring a lustre from her pale green halo on the broad sweeping path of the Canal. The noble curves of the houses to west and south shut out the light; day is past, the reign of night has begun. Then cross to the Zattere: you pass into another day. A full tide flows from east to west, blue and swelling like the sea, dyed in the west a shining orange Where the Euganean hills rise in clear soft outline against the afterglow, while to the east the moon has laid her silver bridle upon the dim waters. Cross to the Giudecca and pass along the narrow, crowded quay into the old palace, which in that deserted corner shows one dim lamp to the canal. The great hall opens at the further end on a bowery garden where a fountain drips in the darkness and the cicalas begin their piping. Mount the winding stair, past the kitchen and the great key-shaped reception room, and look out over the city—across the whole sweep of the magnificent Giudecca Canal and the basin of San Marco. The orange glow is fading and the Euganean hills are dying into the night, while near at hand one great golden star is setting behind the Church of the Redentore, and the moon shines with full brilliance upon the swaying waters, upon the Ducal Palace and the churches of the Zattere, with the Salute as their chief. The night of Venice has begun; she has put on her jewels and is blazing with light. At the back of the house, where the lagoons lie in the shimmering moonlight, is a silent waste of waters under the stars, broken only by the lights of the islands. This also is Venice, this mystery of moonlit water no less than the radiance of the city. And it is possible to come still nearer to the lagoon. Passing along a dark rio little changed from the past, we may cross a bridge into one of the wonderful gardens for which the Giudecca is famous. The families of the Silvi, Barbolini and Istoili, banished in the ninth century for stirring up tumult in the Republic, when at last they were recalled by intercession of Emperor Ludovico, inhabited this island of Spinalunga or Giudecca and laid out gardens there. This one seems made for the night. The moonlight streams through the vine pergolas which cross it in every direction, lights the broad leaves of the banana tree and the dome of the Salute behind the dark cypress-spire, and stars the grass with shining petals. The night is full of the scent of haystacks built along the edge of the lagoon, beside the green terrace which runs the length of the water-wall. Then, as darkness deepens, we leave to the cicalas their moonlit paradise, and glide once more into the Grand Canal. It is at this hour, more than at any other, that, sweeping round the curves of that marvellous waterway, it possesses us as an idea, a presence that is not to be put by, so compelling, so vitally creative, is its beauty. Truly Venice is poetry, and would create a poet out of the dullest clay.

Every one will remember that a few years ago an enterprising man of business attempted with sublime self-confidence to transfer Venice to London, to enclose her within the walls of a great exhibition. Many of us delighted in the miniature market of Rialto, in gliding through the narrow waterways, in the cry of the gondoliers, and the sound of violin and song across the water. But one gift in the portion of Venice was forgotten, a gift which she shares indeed with other cities, but which she alone can put out to interest and increase a thousandfold. The sky is the roof of all the world, but Venice alone is paved with sky; and the streets of Venice with no sky above them are like the wings of the butterfly without the sun. Tintoret and Turner saw Venice as the offspring of sky and water: that is the spirit in which they have portrayed her; that is the essence of her life. It has penetrated everything she has created of enduring beauty. Go into San Marco and look down at what your feet are treading. Venice, whose streets are paved with sky, must in her church also have sky beneath her feet. It is impossible to imagine a more wonderful pavement than the undulating marbles of San Marco; its rich and varied colours bound together with the rarest inspiration; orient gems captured and imprisoned and constantly lit with new and vivid beauty from the domes above. The floor of San Marco is one of the glories of Venice—of the world; and it is surely peculiarly expressive of the inspiration which worked in Venice in the days of her creative life. San Marco, indeed, in its superb and dazzling harmonies of colour, is almost the only living representative of the Venice of pomegranate and gold which created the Cà d’Oro, of the City of Carpaccio and Gentile Bellini, whose cornice-mouldings were interwoven with glittering golden thread, while every side canal gave back a glow of colour from richly-tinted walls. The banners of the Lion in the Piazza no longer wave in solemn splendour of crimson and gold above a pavement of pale luminous red; in their place the tricolour of Italy flaunts over colourless uniformity. The gold is fading from the Palace of the Doges, and only in a few rare nooks, such as the Scuola of the Shoemakers in the Campo San Tomà, do we find the original colours of an old relief linger in delicate gradation over window or door.

Day after day some intimate treasure is torn from the heart of Venice. Since Ruskin wrote, one leaf after another has been cut from the Missal which “once lay open upon the waves, miraculous, like St. Cuthbert’s book, a golden legend on countless leaves.” Those leaves are numbered now. Year by year some familiar object disappears from bridge or doorway, to be labelled and hoarded in a distant museum among aliens and exiles like itself. And here, in Venice itself, a sentiment of distress, the fastidio of the Italians, comes over us as we ponder upon the sculptured relics in the cortile of the Museo Civico. What meaning have they here? It is atmosphere that they need—the natural surroundings that would explain and vivify their forms. Many also of the Venetian churches are despoiled, and their paintings hung side by side with alien subjects in a light they were never intended to bear. The Austrian had less power to hurt Venice than she herself possesses. In those of her sons who understand her malady there flows an undercurrent of deep sadness, as if day by day they watched the ebbing of a life in which all their hope and all their love had root. They cannot sever themselves from Venice: they cannot save her. Venice pretending to share in the vulgar life of to-day, Venice recklessly discarding one glory after another for the poor exchange of coin, still has a power over us not wielded by the inland cities of Italy, happier in the untroubled beauty of their decay. For, as you are turning with sorrow from some fresh sign of pitiless destruction, of a sudden she will flash upon you a new facet of her magic stone, will draw you spell-bound to her waters and weave once more that diaphanous web of radiant mystery:

Za per dirtelo,—o Catina,

La campagna me consola;

Ma Venezia è la sola

Che me possa contentar.

Each of us, face to face with Venice, has a new question to ask of her, and, as he alone framed the question, the answer will be given to him alone. Every stone has not yielded up its secret: in some there may still be a mark yet unperceived beneath the dust. Here and there in her manuscript there may lurk between the lines a word for the skilled or the fortunate. Venice is not yet dumb: every day and every night the sun and moon and star make music in her that has not yet been heard: with patience and love we may redeem here and there a chord of those divine musicians, or at least a tone which shall make her harmony more full.

O Venezia benedetta,

No te vogio più lassar.