Chapter 9

I wanted to go and look at a place right about the middle of the island that I’d found when I was looking around; so we took off walking and soon got to it, because the island was only three miles long and four hundred yards wide.

This place was a long, steep hill about forty foot high. We had a rough time getting to the top, the sides was so steep and the bushes so thick. We walked and climbed around all over it, and by and by found a good big cave in the rock, almost up to the top on the side toward Illinois. The cave was as big as two or three rooms pushed together, and Jim could stand up straight in it. It was cool in there. Jim was for putting our traps in there right away, but I said we didn’t want to be climbing up and down there all the time.

Jim said if the canoe was hiding in a good place near the hill, and we had all the traps in the cave, we could hurry there if anyone was to come to the island, and they would never find us without dogs. And, besides, he said them little birds had said it was going to rain, and did I want the things to get wet?

So we went back and got the canoe, and brought it up opposite the cave, and carried all the traps up there. Then we hunted up a place close by to hide the canoe in, where the willow branches was thick. We took some fish off of the lines and set them again, and started to get ready for dinner.

The door of the cave was big enough to wheel a barrel through it, and on one side of the door the floor projected out a little, and was flat and a good place to build a fire on. So we made it there and cooked dinner.

We put the blankets down inside for a rug, and eat our dinner in there. We put all the other things at the back of the cave. Pretty soon it turned dark, and started to thunder and lightning; so the birds was right about it. Soon after it started to rain, and it rained like all hell, too, and I never seen the wind blow so.

It was one of these real summer storms. It would get so dark that it looked all blue-black outside. It was beautiful; and the rain would come down so thick that the trees off a little ways looked grey and like a spider web; and here would come an explosion of wind that would bend the trees down and turn up the white under side of the leaves; and then an even bigger wind would follow along and make the branches throw their arms as if they was just wild; and next, when it was just about the bluest and blackest -- fst! it was as light as heaven, and you’d have a little show of tree tops a-moving about away off in the distance, hundreds of yards farther than you could see before; dark as sin again in a second, and then you’d hear the thunder let go with an awful noise, and then go groaning and turning down the sky toward the under side of the world, like pushing empty barrels down steps -- where it’s long steps and they jump around a lot, you know.

"Jim, this is nice," I says. "I wouldn’t want to be nowhere else. Pass me another piece of fish and some hot corn bread."

"Well, you wouldn’t a been here if it hadn’t a been for Jim. You’d a been down dere in de trees widout any dinner, and getting almost drowned, too; dat you would, honey. Chickens knows when it’s gwyne to rain, and so do de birds, child."

The river went up higher and higher for ten or twelve days, until at last it was over the sides of the river. The water was three or four foot deep on the island in the low places and on the Illinois bottom. On that side it was a good many miles wide, but on the Missouri side it was the same old distance across -- a half a mile -- because the Missouri side was just a wall of cliffs.

Each day we went all over the island in the canoe. It was pretty cool in under the trees, even if the sun was burning outside. We went bending in and out between the trees, and sometimes the vines were hanging so thick we had to back away and go some other way. Well, on every old broken-down tree you could see rabbits and snakes and such things; and when the island had been flooded a day or two they got so quiet, because of being hungry, that you could take the canoe right up and put your hand on them if you wanted to; but not the snakes and turtles -- they would drop off into the water. The line of hills our cave was in was full of them. We could a had animals enough to play with if we had wanted them.

One night we caught a little piece of a timber raft -- nice boards. It was twelve foot wide and about fifteen or sixteen foot long, and the top stood above water six or seven inches -- a solid, level floor. We could see saw logs go by in the light sometimes, but we let them go; we didn’t show ourselves in the light.

Another night when we was up at the head of the island, just before the sun come up, here comes a whole timber house down, on the west side. She was a big one, and leaning over a lot. We took the canoe out and got on it -- climbed in at a window. But it was too dark to see yet, so we tied the canoe to it and sat there waiting for the sun to come up.

The light started to come before we got to the foot of the island, so we looked in at the window. We could make out a bed, a table, two old chairs, and lots of things around the floor, and there was clothes hanging against the wall. There was something on the floor in the far corner that looked like a man.

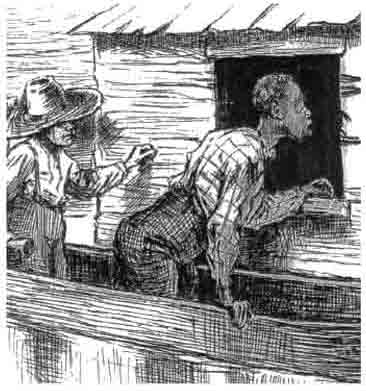

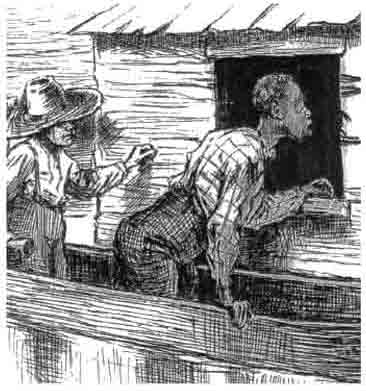

So Jim says: "Hello, you!"

But it didn’t move. So I shouted again, then Jim says: "He ain’t asleep -- he’s dead. You hold here -- I’ll go see." He went in, and got down close and looked, and says:

"It’s a dead man. Yes, it is; with no clothes on, too. He got a bullet in de back. I’d say he’s been dead two or three days. Come in, Huck, but don’t look at his face -- it’s too awful."

I didn’t look at him at all. Jim throwed some old dirty cloths over him, but there was no need for that; I didn’t want to see him. There was lots of old dirty cards all around over the floor, and old whiskey bottles, and two masks made out of black cloth; and all over the walls was the stupidest kind of words and pictures made with coals from a fire. There was two old dirty dresses, and a sun hat, and some women’s under clothes hanging against the wall, and some men’s clothes, too. We put the lot into the canoe -- maybe we could find a use for them. There was a boy’s old hat on the floor; I took that, too. And there was a bottle that had had milk in it, and it had a piece of cloth in it for a baby to put in its mouth to get milk from it. We would of took the bottle, but it was broken. There was a dirty old timber box, and an old broken suitcase. They was open, but there weren’t nothing left in them that was of any good to us. The way things was all over the place we said to ourselves that the people must of left in a hurry, and weren’t fixed so as to carry off most of their things.

We got an old tin lantern, and a sharp meat knife without any handle, and a nice new knife worth money in any shop, and a lot of candles made from fat, and a tin stick to hold a candle, and a tin cup, and a dirty old quilt off the bed, and a hand bag with needles and wax and buttons and thread and all such things in it, and an axe and some nails, and a fish line as thick as my little finger with some very big hooks on it, and a big piece of leather, and a horse shoe, and some bottles of medicine that didn’t have no name on them; and just as we was leaving Jim found a dirty old violin bow, and a timber leg. The belts to hold it on was broken off of it, but, apart from that, it was a good enough leg, but it was too long for me and not long enough for Jim, and we couldn’t find the other one, even after hunting all around.

And so, take it all around, we made a good time of it. When we was ready to leave we was four hundred yards below the island, and it was pretty much light outside; so I made Jim lay down in the canoe and cover up with the quilt, because if he set up people could tell he was a black man a good ways off. I took the boat over to the Illinois side, and was pushed down the river almost a half a mile doing it. I worked my way back up to the island in the dead water under the high ground on that side, and hadn’t no accidents and didn’t see nobody. We got home all safe.