Chapter 10

After breakfast I wanted to talk about the dead man and about how he come to be killed, but Jim didn’t want to. He said it would bring bad luck; and on top of that, he said, his ghost might come looking for us; he said a man that weren’t buried would more often do that than one that was planted and com- fortable. That sounded pretty true, so I didn’t say no more; but I couldn’t stop from studying over it and wishing I knowed who killed the man, and what they done it for.

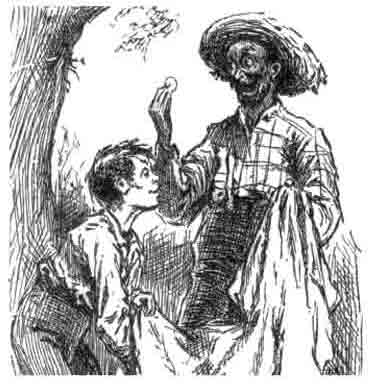

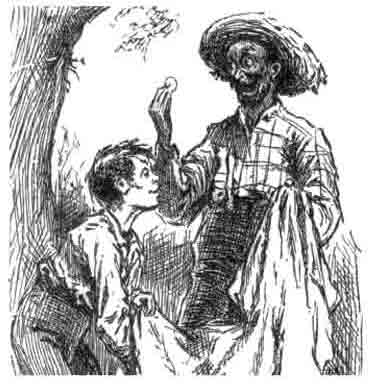

We went through the clothes we’d got, and found eight dollars in silver sewed up inside an old coat.

Jim said he had a feeling the people robbed the coat and didn’t know it had money in it, because if they’d a-knowed they wouldn’t a left it. I said I had a feeling they killed him, too; but Jim didn’t want to talk about that.

I says: "Now you think it’s bad luck; but what did you say when I showed you the snake skin that I found on the top of the hill day before yesterday? You said it was the worst bad luck in the world to touch a snake skin with my hands. Well, here’s your bad luck! We’ve brought in all these things and eight dollars on top of it. I wish we could have some bad luck like this every day, Jim."

"Never you mind, honey, never you mind. Don’t you get too smart. It’s a-coming. Remember I tell you, it’s a-coming."

It did come, too. It was a Tuesday that we had that talk. Well, after dinner Friday we was lying around in the grass at the highest end of the hill, and got out of tobacco. I went to the cave to get some, and found a rattlesnake in there. I killed him, and put him on the foot of Jim’s blanket, ever so alive looking, thinking there’d be some fun when Jim found him there. Well, that night I wasn't thinking about the snake, and when Jim threw himself down on the blanket as I was lighting a candle the snake’s mate was there, and took a bite of him.

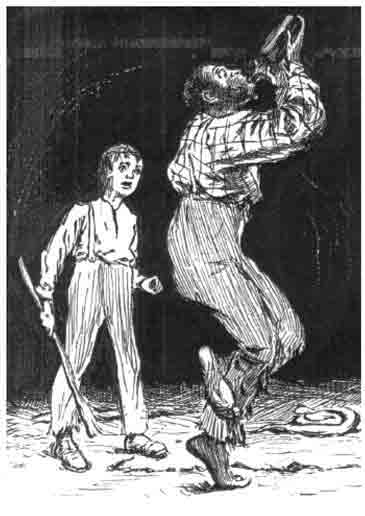

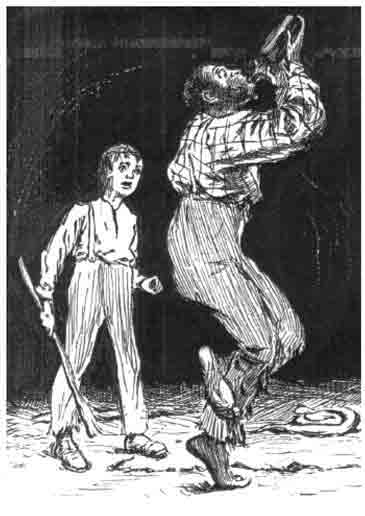

He jumped up shouting, and the first thing the light showed was the snake coiled up for another jump at him. I killed it in a second with a stick, and Jim picked up pap’s whiskey bottle and started to pour it down his throat.

He had no shoes on, and the snake went for him right on the heel. That all comes of my being so stupid as to not remember that wherever you leave a dead snake its mate always comes there and hugs it. Jim told me to cut off the snake’s head and throw it away, and then skin the body and cook a piece of it. I done it, and he eat it and said it would help him heal. He made me take off the rattles and tie them around his wrist, too. Then I went out quiet and throwed the snakes clear away in the bushes; for I weren’t going to let Jim find out it was me that brought the snake’s mate there, not if I could help it.

Jim kept on drinking at the whiskey, and now and then he got out of his head and ran around and shouted; but every time he come to himself he went to drinking whiskey again. His foot went up pretty big, and so did his leg; but by and by the effect of drinking started to come, and so I judged he was all right; but I think it would be better the snake’s bite than pap’s whiskey.

Jim was sick for four days and nights. Then his leg went back down and he was around again. I said to myself then I wouldn’t ever take hold of a snake skin again with my hands, now that I see what had come of it. Jim said he could see I would believe him next time. And he said that handling a snake skin was such awful bad luck that maybe we hadn’t got to the end of it yet. He said he would be happier to see the new moon over his left shoulder as much as a thousand times than take up a snake skin in his hand. Well, I was getting to feel that way myself. Still, I’ve always said that looking at the new moon over your left shoulder is one of the most dangerous and foolish things a body can do. Old Hank Bunker done it once, and talked proud of it; and in less than two years he got drunk and fell off of a tower, and hit the ground so hard that he was just as thin as a blanket, as you may say; and they put him like that between two barn doors, and buried him like that, so they say, but I didn’t see it. Pap told me. But anyway it all come of looking at the moon that way, like a stupid person.

Well, the days went along, and the river went down between its sides again; and about the first thing we done was to put meat from a skinned rabbit on one of the big hooks and catch a catfish that was as big as a man, being six foot two inches long, and weighed over two hundred pounds. It’s easy to see that we couldn’t handle him; he would a throwed us into Illinois. We just sat there and watched him throw himself around until he died. We found a metal button in his stomach and a round ball, and lots of other things. We cut the ball open with the axe, and there was a thread cylinder in it. Jim said he’d had it there a long time, to cover it over so with chemicals from his stomach and make a ball of it. It was as big a fish as was ever caught in the Mississippi, I’d say. Jim said he hadn’t ever seen a bigger one. He would a been worth a lot of money over at the village. They sell out such a fish as that one by the pound in the market there; everybody buys some of him; his meat’s as white as snow and makes a good meal.

Next morning I said it was getting slow and boring, and I wanted to get some action up some way. I said I would just go quietly over the river and find out what was happening. Jim liked that plan; but he said I must go in the dark and look sharp. Then he studied it over and said, couldn’t I put on some of them old things and dress up like a girl? That was a good plan, too. So we made one of the dresses a little shorter, and I turned up my pant legs to my knees and got into it. Jim tied it behind with the hooks, and it was a good job. I put on the sun hat and tied it, so that for a body to look in and see my face was like looking down a stove pipe with a bend in it. Jim said nobody would know me, even in the light of day. I worked at it all day to get the feel of the things, and by and by I could do pretty well in them, only Jim said I didn’t walk like a girl; and he said I must quit pulling up my dress to get at my pocket. I listened to him, and done better.

I started up the Illinois side in the canoe just after dark. Then I started across to the town from a little below the ferry landing. The movement of the river brought me in at the bottom of the town. I tied up and walked along the side of the river. There was a light burning in a little cabin that hadn’t been lived in for a long time, and I wanted to know who had took up living there. I moved qui- etly up and looked in at the window. There was a woman about forty years old in there knitting by a candle that was on a timber table.

I didn’t know her face; she was a stranger, for you couldn’t show a face in that town that I didn’t know. Now this was lucky, because I had been starting to fear; I was getting afraid that people might know my voice and find me out. But if this woman had been in such a little town even two days she could probably tell me all I wanted to know; so I knocked at the door, and promised myself I wouldn’t forget I was a girl.