hack it out on al the temple wals. The names also of other gods were erased; and it is

noticeable in this tomb that the word mut, meaning "mother," was carefuly spelt in hieroglyphs

which would have no similarity to those used in the word Mut, the goddess-consort of Amon.

The name of Amenhotep III., his own father, did not escape the King's wrath, and the first

sylables were everywhere erased.

As the years went by Akhnaton seems to have given himself more and more completely to his [203]

new religion. He had now so trained one of his nobles, named Merira, in the teachings of Aton

that he was able to hand over to him the high priesthood of that god, and to turn his attention

to the many other duties which he had imposed upon himself. In rewarding Merira, the King is

related to have said, "Hang gold at his neck before and behind, and gold on his legs, because

of his hearing the teaching of Pharaoh concerning every saying in these beautiful places."

Another official whom Akhnaton greatly advanced says: "My lord advanced me because I

have carried out his teaching, and I hear his word without ceasing." The King's doctrines were

thus beginning to take hold; but one feels, nevertheless, that the nobles folowed their King

rather for the sake of their material gains than for the spiritual comforts of the Aton-worship.

There is reason to suppose that at least one of these nobles was degraded and banished from

the city.

But while Akhnaton was preaching peace and goodwil amidst the flowers of the temple of

Aton, his generals in Asia Minor were vainly struggling to hold together the great empire

created by Thutmosis III. Akhnaton had caused a temple of Aton to be erected at one point

in Syria at least, but in other respects he took little or no interest in the welfare of his foreign

dominions. War was not tolerated in his doctrine: it was a sin to take away life which the good

Father had given. One pictures the hardened soldiers of the empire striving desperately to [204]

hold the nations of Asia faithful to the Pharaoh whom they never saw. The smal garrisons

were scattered far and wide over Syria, and constantly they sent messengers to the Pharaoh

asking at least for some sign that he held them in mind.

There is no more pathetic page of ancient history than that which tels of the fal of the

Egyptian Empire. The Amorites, advancing along the sea-coast, took city after city from the

Egyptians almost without a struggle. The chiefs of Tunip wrote an appeal for help to the King:

"To the King of Egypt, my lord,—The inhabitants of Tunip, thy servant." The plight of the city

is described and reinforcements are asked for, "And now," it continues, "Tunip thy city weeps,

and her tears are flowing, and there is no help for us. For twenty years we have been sending

to our lord the King, the King of Egypt, but there has not come a word to us, no, not one."

The messengers of the beleaguered city must have found the King absorbed in his religion,

and must have seen only priests of the sun where they had hoped to find the soldiers of former

days. The Egyptian governor of Jerusalem, attacked by Aramæans, writes to the Pharaoh,

saying: "Let the King take care of his land, and ... let send troops.... For if no troops come in

this year, the whole territory of my lord the King wil perish." To this letter is added a note to

the King's secretary, which reads, "Bring these words plainly before my lord the King: the [205]

whole land of my lord the King is going to ruin."

So city after city fel, and the empire, won at such cost, was gradualy lost to the Egyptians. It

is probable that Akhnaton had not realised how serious was the situation in Asia Minor. A

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

106/160

few of the chieftains who were not actualy in arms against him had written to him every now

and then assuring him that al was wel in his dominions; and, strange to relate, the tribute of

many of the cities had been regularly paid. The Asiatic princes, in fact, had completely fooled

the Pharaoh, and had led him to believe that the nations were loyal while they themselves

prepared for rebelion. Akhnaton, hating violence, had been only too ready to believe that the

despatches from Tunip and elsewhere were unjustifiably pessimistic. He had hoped to bind

together the many countries under his rule, by giving them a single religion. He had hoped that

when Aton should be worshipped in al parts of his empire, and when his simple doctrines of

love, truth, and peace should be preached from every temple throughout the length and

breadth of his dominions, then war would cease and a unity of faith would hold the lands in

harmony one with the other.

When, therefore, the tribute suddenly ceased, and the few refugees came staggering home to

tel of the perfidy of the Asiatic princes and the fal of the empire, Akhnaton seems to have [206]

received his deathblow. He was now not more than twenty-eight years of age; and though his

portraits show that his face was already lined with care, and that his body was thinner than it

should have been, he seems to have had plenty of reserve strength. He was the father of

several daughters, but his queen had borne him no son to succeed him; and thus he must have

felt that his religion could not outlive him. With his empire lost, with Thebes his enemy, and

with his treasury welnigh empty, one feels that Akhnaton must have sunk to the very depths of

despondency. His religious revolution had ruined Egypt, and had failed: did he, one wonders,

find consolation in the sunshine and amidst the flowers?

His death folowed speedily; and, resting in the splendid coffin in which we found him, he was

laid in the tomb prepared for him in the hils behind his new capital. The throne fel to the

husband of one of his daughters, Smenkhkara, who, after an ephemeral reign, gave place to

another of the sons-in-law of Akhnaton, Tutankhaton. This king was speedily persuaded to

change his name to Tutankhamon, to abandon the worship of Aton, and to return to Thebes.

Akhnaton's city fel into ruins, and soon the temples and palaces became the haunt of jackals

and the home of owls. The nobles returned with their new king to Thebes, and not one [207]

remained faithful to those "teachings" to which they had once pretended to be such earnest

listeners.

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

107/160

[Photo by R. Paul.

The coffin of Akhnaton lying in the tomb of Queen Tiy.

PL. XX.

The fact that the body in the new tomb was that of Akhnaton, and not of Queen Tiy, gives a

new reading to the history of the burial. When Tutankhamon returned to Thebes, Akhnaton's

memory was stil, it appears, regarded with reverence, and it seems that there was no question

of leaving his body in the neighbourhood of his deserted palace, where, until the discovery of

this tomb, Egyptologists had expected to find it. It was carried to Thebes, together with some

of the funeral furniture, and was placed in the tomb of Queen Tiy, which had been reopened

for the purpose. But after some years had passed and the priesthood of Amon-Ra had again

asserted itself, Akhnaton began to be regarded as a heretic and as the cause of the loss of

Egypt's Asiatic dominions. These sentiments were vigorously encouraged by the priesthood,

and soon Akhnaton came to be spoken of as "that criminal," and his name was obliterated

from his monuments. It was now felt that his body could no longer lie in state together with

that of Queen Tiy in the Valey of the Tombs of the Kings. The sepulchre was therefore

opened once more, and the name Akhnaton was everywhere erased from the inscriptions.

The tomb, poluted by the presence of the heretic, was no longer fit for Tiy, and the body of

the Queen was therefore carried elsewhere, perhaps to the tomb of her husband Amenhotep [208]

III. The shrine in which her mummy had lain was puled to pieces and an attempt was made to

carry it out of the tomb; but this arduous task was presently abandoned, and one portion of

the shrine was left in the passage, where we found it. The body of Akhnaton, his name erased,

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

108/160

was now the sole occupant of the tomb. The entrance was blocked with stones, and sealed

with the seal of Tutankhamon, a fragment of which was found; and it was in this condition that

it was discovered in 1907.

The bones of this extraordinary Pharaoh are in the Cairo Museum; but, in deference to the

sentiments of many worthy persons, they are not exhibited. The visitor to that museum,

however, may now see the "canopic" jars, the alabaster vases, the gold vulture, the gold

necklace, the sheets of gold in which the body was wrapped, the toilet utensils, and parts of

the shrine, al of which we found in the burial-chamber.

[TABLE OF CONTENTS]

CHAPTER IX.

[209]

THE TOMB OF HOREMHEB.

In the last chapter a discovery was recorded which, as experience has shown, is of

considerable interest to the general reader. The romance and the tragedy of the life of

Akhnaton form a realy valuable addition to the store of good things which is our possession,

and which the archæologist so diligently labours to increase. Curiously enough, another

discovery, that of the tomb of Horemheb, was made by the same explorer (Mr Davis) in

1908; and as it forms the natural sequel to the previous chapter, I may be permitted to record

it here.

Akhnaton was succeeded by Smenkhkara, his son-in-law, who, after a brief reign, gave place

to Tutankhamon, during whose short life the court returned to Thebes. A certain noble named

Ay came next to the throne, but held it for only three years. The country was now in a chaotic

condition, and was utterly upset and disorganised by the revolution of Akhnaton, and by the

vacilating policy of the three weak kings who succeeded him, each reigning for so short a [210]

time. One cannot say to what depths of degradation Egypt might have sunk had it not been for

the timely appearance of Horemheb, a wise and good ruler, who, though but a soldier of not

particularly exalted birth, managed to raise himself to the vacant throne, and succeeded in so

organising the country once more that his successors, Rameses I., Sety I., and Rameses II.,

were able to regain most of the lost dominions, and to place Egypt at the head of the nations

of the world.

Horemheb, "The Hawk in Festival," was born at Alabastronpolis, a city of the 18th Province

of Upper Egypt, during the reign of Amenhotep III., who has rightly been named "The

Magnificent," and in whose reign Egypt was at once the most powerful, the most wealthy, and

the most luxurious country in the world. There is reason to suppose that Horemheb's family

were of noble birth, and it is thought by some that an inscription which cals King Thutmosis

III. "the father of his fathers" is to be taken literaly to mean that that old warrior was his great-

or great-great-grandfather. The young noble was probably educated at the splendid court of

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

109/160

Amenhotep III., where the wit and intelect of the world was congregated, and where, under

the presidency of the beautiful Queen Tiy, life slipped by in a round of revels.

As an impressionable young man, Horemheb must have watched the gradual development of

freethought in the palace, and the ever-increasing irritation and chafing against the bonds of [211]

religious convention which bound al Thebans to the worship of the god Amon. Judging by his

future actions, Horemheb did not himself feel any real repulsion to Amon, though the religious

rut into which the country had falen was sufficiently objectionable to a man of his intelect to

cause him to cast in his lot with the movement towards emancipation. In later life he would

certainly have been against the movement, for his mature judgment led him always to be on

the side of ordered habit and custom as being less dangerous to the national welfare than a

social upheaval or change.

Horemheb seems now to have held the appointment of captain or commander in the army,

and at the same time, as a "Royal Scribe," he cultivated the art of letters, and perhaps made

himself acquainted with those legal matters which in later years he was destined to reform.

When Amenhotep III. died, the new king, Akhnaton, carried out the revolution which had

been pending for many years, and absolutely banned the worship of Amon, with al that it

involved. He built himself a new capital at El Amârna, and there he instituted the worship of

the sun, or rather of the heat or power of the sun, under the name of Aton. In so far as the

revolution constituted a breaking away from tiresome convention, the young Horemheb seems

to have been with the King. No one of inteligence could deny that the new religion and new [212]

philosophy which was preached at El Amârna was more worthy of consideration on general

lines than was the narrow doctrine of the Amon priesthood; and al thinkers must have

rejoiced at the freedom from bonds which had become intolerable. But the world was not

ready, and indeed is stil not ready, for the schemes which Akhnaton propounded; and the

unpractical model-kingdom which was uncertainly developing under the hils of El Amârna

must have already been seen to contain the elements of grave danger to the State.

Nevertheless the revolution offered many attractions. The frivolous members of the court,

always ready for change and excitement, welcomed with enthusiasm the doctrine of the moral

and simple life which the King and his advisers preached, just as in the decadent days before

the French Revolution the court, bored with licentiousness, gaily welcomed the morality-

painting of the young Greuze. And to the more serious-minded, such as Horemheb seems to

have been, the movement must have appealed in its imperial aspect. The new god Aton was

largely worshipped in Syria, and it seems evident that Akhnaton had hoped to bind together

the heterogeneous nations of the empire by a bond of common worship. The Asiatics were

not disposed to worship Amon, but Aton appealed to them as much as any god, and [213]

Horemheb must have seen great possibilities in a common religion.

It is thought that Horemheb may be identified amongst the nobles who folowed Akhnaton to

El Amârna, and though this is not certain, there is little doubt that he was in high favour with

the King at the time. To one whose tendency is neither towards frivolity nor towards

fanaticism, there can be nothing more broadening than the influence of religious changes. More

than one point of view is appreciated: a man learns that there are other ruts than that in which

he runs, and so he seeks the smooth midway. Thus Horemheb, while acting loyaly towards

his King, and while appreciating the value of the new movement, did not exclude from his

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

110/160

thoughts those teachings which he deemed good in the old order of things. He seems to have

seen life broadly; and when the new religion of Akhnaton became narrowed and fanatical, as

it did towards the close of the tragic chapter of that king's short life, Horemheb was one of the

few men who kept an open mind.

Like many other nobles of the period, he had constructed for himself a tomb at Sakkâra, in

the shadow of the pyramids of the old kings of Egypt; and fragments of this tomb, which of

course was abandoned when he became Pharaoh, are now to be seen in various museums. In

one of the scenes there sculptured Horemheb is shown in the presence of a king who is almost

certainly Akhnaton; and yet in a speech to him inscribed above the reliefs, Horemheb makes [214]

reference to the god Amon whose very name was anathema to the King. The royal figure is

drawn according to the canons of art prescribed by Akhnaton, and upon which, as a protest

against the conventional art of the old order, he laid the greatest stress in his revolution; and

thus, at al events, Horemheb was in sympathy with this aspect of the movement. But the

inscriptions which refer to Amon, and yet are impregnated with the Aton style of expression,

show that Horemheb was not to be held down to any one mode of thought. Akhnaton was,

perhaps, already dead when these inscriptions were added, and thus Horemheb may have

had no further reason to hide his views; or it may be that they constituted a protest against that

narrowness which marred the last years of a pious king.

Those who read the history of the period in the last chapter wil remember how Akhnaton

came to persecute the worshippers of Amon, and how he erased that god's name wherever it

was written throughout the length and breadth of Egypt. Evidently with this action Horemheb

did not agree; nor was this his only cause for complaint. As an officer, and now a highly

placed general of the army, he must have seen with feelings of the utmost bitterness the

neglected condition of the Syrian provinces. Revolt after revolt occurred in these states; but

Akhnaton, dreaming and praying in the sunshine of El Amârna, would send no expedition to [215]

punish the rebels. Good-felowship with al men was the King's watchword, and a policy more

or less democratic did not permit him to make war on his felow-creatures. Horemheb could

smel battle in the distance, but could not taste of it. The battalions which he had trained were

kept useless in Egypt; and even when, during the last years of Akhnaton's reign, or under his

successor Smenkhkara, he was made commander-in-chief of al the forces, there was no

means of using his power to check the loss of the cities of Asia. Horemheb must have

watched these cities fal one by one into the hands of those who preached the doctrine of the

sword, and there can be little wonder that he turned in disgust from the doings at El Amârna.

During the times which folowed, when Smenkhkara held the throne for a year or so, and

afterwards, when Tutankhamon became Pharaoh, Horemheb seems to have been the leader

of the reactionary movement. He did not concern himself so much with the religious aspect of

the questions: there was as much to be said on behalf of Aton as there was on behalf of

Amon. But it was he who knocked at the doors of the heart of Egypt, and urged the nation to

awake to the danger in the East. An expedition against the rebels was organised, and one

reads that Horemheb was the "companion of his Lord upon the battlefield on that day of the

slaying of the Asiatics." Akhnaton had been opposed to warfare, and had dreamed that dream [216]

of universal peace which stil is a far-off light to mankind. Horemheb was a practical man in

whom such a dream would have been but weakness; and, though one knows nothing more of

these early campaigns, the fact that he attempted to chastise the enemies of the empire at this

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

111/160

juncture stands to his credit for al time.

Under Tutankhamon the court returned to Thebes, though not yet exclusively to the worship

of Amon; and the political phase of the revolution came to an end. The country once more

settled into the old order of life, and Horemheb, having experienced the ful dangers of

philosophic speculation, was glad enough to abandon thought for action. He was now the

most powerful man in the kingdom, and inscriptions cal him "the greatest of the great, the

mightiest of the mighty, presider over the Two Lands of Egypt, general of generals," and so

on. The King "appointed him to be Chief of the Land, to administer the laws of the land as

Hereditary Prince of al this land"; and "al that was done was done by his command." From

chaos Horemheb was producing order, and al men turned to him in gratitude as he

reorganised the various government departments.

The offices which he held, such as Privy Councilor, King's Secretary, Great Lord of the

People, and so on, are very numerous; and in al of these he dealt justly though sternly, so that

"when he came the fear of him was great in the sight of the people, prosperity and health were [217]

craved for him, and he was greeted as 'Father of the Two Lands of Egypt.'" He was indeed

the saviour and father of his country, for he had found her corrupt and disordered, and he was

leading her back to greatness and dignity.

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

112/160

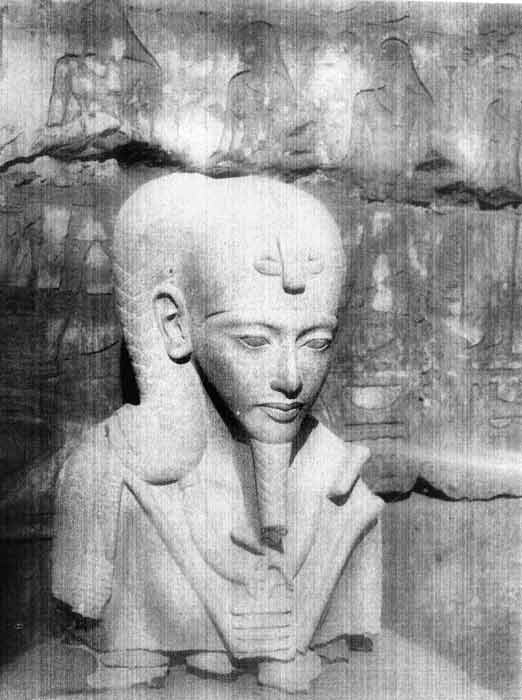

[Photo by Beato.

Head of a granite statue of the god Khonsu, probably dating from about the period of

Horemheb.—CAIRO MUSEUM.

PL. XXI.

At this time he was probably a man of about forty years of age. In appearance he seems to

have been noble and good to look upon. "When he was born," says the inscription, "he was

clothed with strength: the hue of a god was upon him"; and in later life, "the form of a god was

in his colour," whatever that may mean. He was a man of considerable eloquence and great

learning. "He astonished the people by that which came out of his mouth," we are told; and

"when he was summoned before the King the palace began to fear." One may picture the

www.gutenberg.org/files/16160/16160-h/16160-h.htm

113/160

weak Pharaoh and his corrupt court, as they watched with apprehension the movements of

this stern soldier, of whom it was said that his every thought was "in the footsteps of the

Ibis,"—the ibis being the god of wisdom.

On the death of Tutankhamon, the question of inviting Horemheb to fil the vacant throne must

have been seriously considered; but there was another candidate, a certain Ay, who had been

one of the most important nobles in the group of Akhnaton's favourites at El Amârna, and

who had been the loudest in the praises of Aton. Religious feeling was at the time running high,

for the partizans of Amon and those of Aton seem to have been waging war on one another; [218]

and Ay appears to have been regarded as the man most likely to bridge the gulf between the

two parties. A favourite of Akhnaton, and once a devout worshipper of Aton, he was not

averse to the cults of other gods; and by conciliating both factions he managed to obtain the

throne for himself. His power, however, did not last for long; and as the priests of Amon

regained the confidence of the nation at the expense of those of Aton, so the power of Ay

declined. His past connections with Akhnaton told against him, and after a year or so he

disappeared, leaving the throne vacant once more.

There was now no question as to who should succeed. A princess named Mutnezem, the

sister of Akhnaton's queen, and probably an old friend of Horemheb, was the sole heiress to

the throne, the last surviving member of the greatest Egyptian dynasty. Al men turned to

Horemheb in the hope that he would marry this lady, and thus reign as Pharaoh over them,

perhaps leaving a son by her to succeed him when he was gathered to his fathers. He was

now some forty-five years of age, ful of energy and vigour, and passionately anxious to have

a free hand in the carrying out of his schemes for the reorganisation of the government. It was

therefore with joy that, in about the year 1350 B.C., he sailed up to Thebes in order to claim

the crown.

He arrived at Luxor at a time when the annual festival of Amon was being celebrated, and al

the city was en fête. The statue of the god had been taken from its shrine at Karnak, and had [219]

been towed up the river to Luxor in a gorgeous barge, attended by a fleet of gaily-decorated

vessels. With songs and dancing it had been conveyed into the Luxor temple, where the

priests had received it standing amidst piled-up masses of flowers, fruit, and other offerings. It

seems to have been at this moment that Horemheb appeared, while the clouds of incense

streamed up to heaven, and the morning air was ful of the sound of the harps and the lutes.

Surrounded by a crowd of his admirers, he was conveyed into the presence of the divine

figure, and was there and then hailed as Pharaoh.

From the temple he was carried amidst cheering throngs to the palace which stood near by;

and there he was greeted by the Princess Mutnezem, who fel on her knees before him and

embraced him. That