CHAPTER XVIII

A HOLIDAY AND NEW SUCCESSES

But this revelation of my strength rendered more painful to me the sort of idleness to which Perrin condemned me. In fact, after Zaïre, I remained months without anything of importance—playing here and there. Then, discouraged and disgusted with the theater, I renewed my passion for sculpture. After my ride I took a light repast and then fled to my studio where I remained till the evening.

Friends came to see me, sat around me, played the piano, sang, warmly discussed politics—for in this modest studio I received the most illustrious men of all parties. Several ladies came to take tea, which was abominable and badly served; but I did not care about that. I was absorbed by that admirable art. I saw nothing, or to speak more truly. I would not see anything.

At this time I was making the bust of an adorable young girl, Mlle. Emmy de X——. Her slow and measured conversation had an infinite charm. She was a foreigner but spoke French so perfectly that I was stupefied. She smoked a cigarette all the time and had a profound disdain for those who did not understand her.

I made the sittings last as long as possible, for I felt that this delicate spirit was imbuing me with her science of seeing into the beyond, and often in the serious steps of my life I have said to myself: “What would Emmy have done?... What would she have thought?...”

I was somewhat surprised one day by the visit of Adolphe de Rothschild, who came to give me an order for his bust. I commenced the work immediately. But I had not properly considered this admirable man—he had nothing of the æsthetic, but the contrary. I tried, nevertheless, and I brought all my will to bear in order to succeed in this first order of which I was so proud. Twice I dashed the bust which I had commenced on the ground, and after a third attempt I definitely gave it up, stammering idiotic excuses which apparently did not convince my model, for he never returned to me. When we met, in our morning rides, he saluted me with a cold and rather severe bow.

After this defeat I undertook the bust of a beautiful child, Mlle. Multon, a delicious little American whom later on I came across in Denmark, married and the mother of a family—but still as pretty as ever. Then I made a bust of Mlle. Hocquigny, that admirable person who was keeper of the linen in the hospital cars during the war and who had so efficiently helped me and my wounded at that time.

Then I undertook the bust of my young sister Régina, who had, alas, a weak chest. A more perfect face was never made by the hand of God! Two leonine eyes, shaded by long brown lashes—so long that they made a shadow on her cheeks when she lowered them—a slender nose with delicate nostrils, a tiny mouth, a willful chin and a pearly skin, crowned by meshes of sun rays, for I have never seen hair so blond and so pale, so bright and so silky. But this admirable face was without charm: the expression was hard and the mouth without smile. I tried my best to reproduce this beautiful face in marble, but it needed a great artist and I was only a humble amateur.

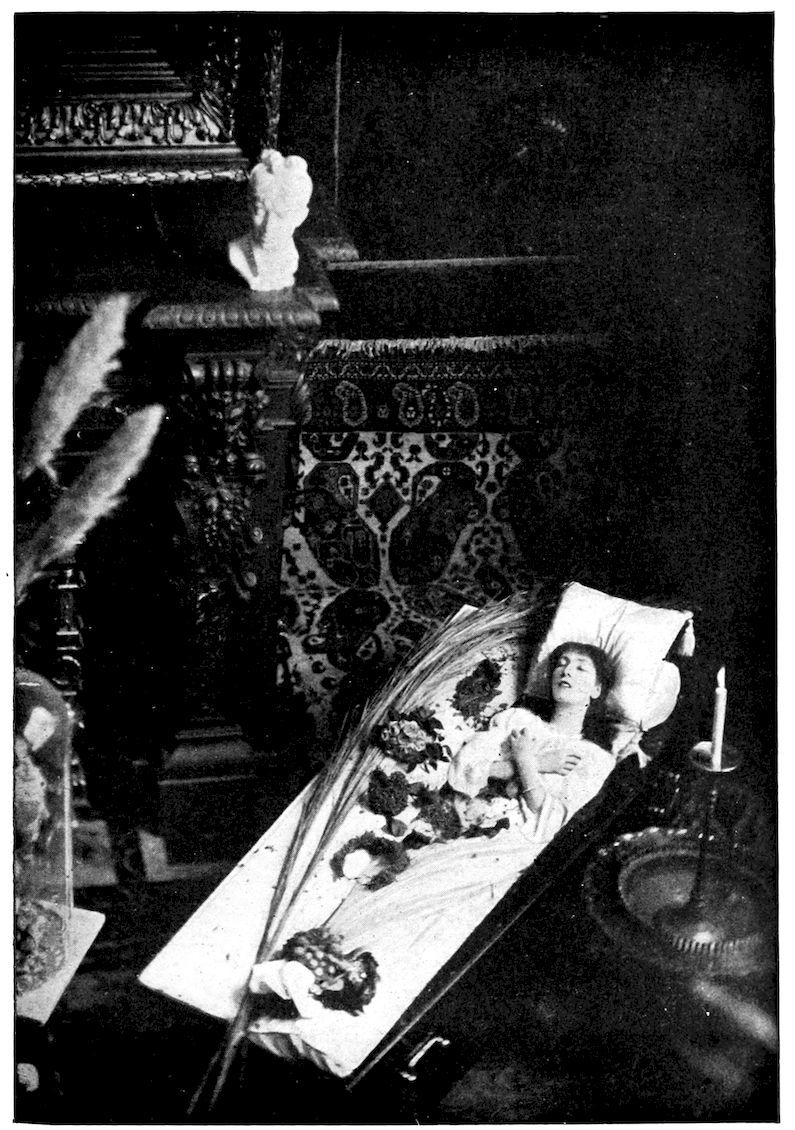

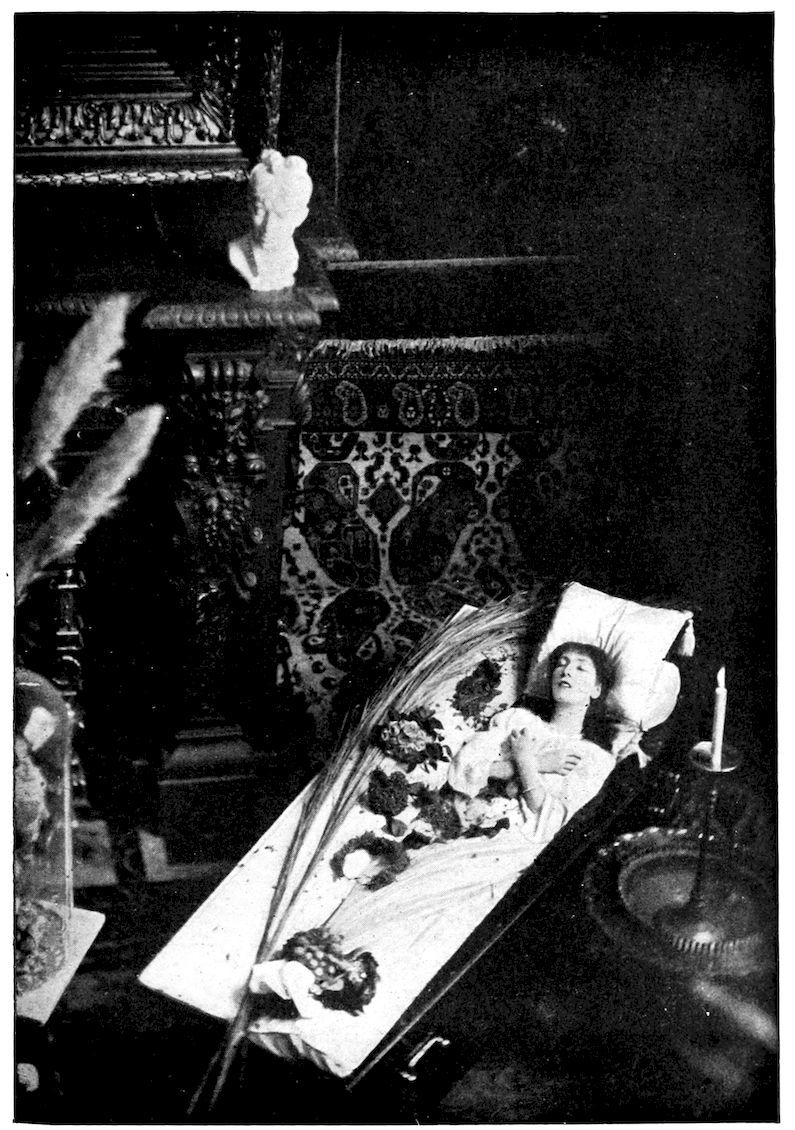

When I exhibited the bust of my little sister, it was five months after her death, which occurred after a six months’ illness full of false hopes. I had taken her to my home, No. 4 Rue de Rome, to the little entresol which I had inhabited since the terrible fire which had destroyed my furniture, my books, my pictures, and all my scant possessions. This apartment in the Rue de Rome was small. My bedroom was very tiny. The big bamboo bed took up all the room. In front of the window was my coffin, where I frequently installed myself to learn my parts. Therefore when I took my sister to my home I found it quite natural to sleep every night in this little bed of white satin which was to be my last couch, and to put my sister in the big bamboo bed under the lace hangings. She herself found it quite natural, also, for I would not leave her at night and it was impossible to put another bed in this room. Besides, she was accustomed to my coffin.

Three days after this new arrangement my manicure came into the room to do my hands and my sister asked her to enter quietly because I was still asleep. The woman turned her head, believing that I was asleep in the armchair, but seeing me in my coffin she rushed away, shrieking wildly. From that moment all Paris knew that I slept in my coffin, and gossip with its thistledown wings took flight in all directions.

I was so accustomed to the turpitudes which were written about me that I did not trouble about this. But at the death of my poor little sister a tragic-comic incident happened: when the undertaker’s men came to the room to take away the body they found themselves confronted with two coffins, and losing his wits, the master of ceremonies sent in haste for a second hearse. I was at that moment with my mother, who had lost consciousness, and I got back just in time to prevent the black-clothed men taking away my coffin. The second hearse was sent back, but the papers got hold of this incident. I was blamed, criticised, etc.

After the death of my sister I fell seriously ill. I had tended her day and night, and this, in addition to the grief I was suffering, made me anæmic. I was ordered to the South for two months. I promised to go to Mentone and I turned immediately toward Bretagne, the country of my dreams. I had with me my little boy, my butler and his wife. My poor Guérard, who had helped me to tend my sister, was in bed ill with phlebitis. I would have much liked to have had her with me.

SARAH BERNHARDT IN HER COFFIN.

Oh, the lovely holiday that we had there! Thirty-five years ago Bretagne was wild, inhospitable, but as beautiful—perhaps more beautiful than at present, for it was not furrowed with roads, its green slopes were not dotted with small white villas, its inhabitants—the men—were not dressed in the abominable modern trousers, nor the women in the miserable little hat and feathers. No, the Bretons proudly displayed their well-shaped legs in gaiters or rough stockings, their feet shod with buckled shoes, their long hair was brought down on the temples, hiding any awkward ears, and giving to the face a nobility which the modern style does not admit of. The women, with their short skirts, which showed their slender ankles in black stockings, and with their small heads under the wings of the headdress, resembled seagulls. I am not speaking, of course, of the inhabitants of Pont l’Abbé or of Bourg de Batz, who have entirely different aspects.

I visited nearly the whole of Bretagne and stayed especially at Finistère. The Pointe du Raz enchanted me. I remained twelve days at Audierne, in the house of the Père Batifoulé, so big and so fat that they had been obliged to cut a piece out of the table to take in his immense abdomen. I set out every morning at ten o’clock. My butler Claude himself prepared my lunch, which he packed up very carefully in three little baskets; then climbing into the comical vehicle of the Père Batifoulé, my little boy driving, we set out for the Baie des Trépassés. Ah, that beautiful and mysterious shore, all bristling with rocks, all pale and sorrowful! The lighthouse keeper would be looking out for me and would come to meet me. Claude gave him my provisions with a thousand recommendations as to the manner of cooking the eggs, warming up the lentils, and toasting the bread. He carried off everything, then returned with two old sticks in which he had stuck nails to make them into picks and we recommenced the terrifying ascension of the Pointe du Raz, a kind of labyrinth full of disagreeable surprises; of crevasses across which we had to jump, over the gaping and roaring abyss; of arches and tunnels through which we had to crawl on all fours, having overhead—touching even—a rock which had fallen there in unknown ages and was only held in equilibrium by some inexplicable phenomena. Then, all at once, the way became so narrow that it was impossible to walk straight forward; we had to turn and put our backs against the rock and advance with both arms spread out and fingers holding on to the few projections of the rock.

When I think of what I did in those moments, I tremble, for I have always been and still am, subject to fits of dizziness. I went over this path along a steep precipitous rock, thirty meters high, in the midst of the infernal noise of the sea, at this place eternally furious and raging fearfully against indestructible rock. And I must have taken a mad pleasure in it, for I accomplished this journey five times in eleven days.

After this challenge thrown down to reason, we descended and installed ourselves in the Baie des Trépassés. After a bath we had lunch and I painted till sunset.

The first day there was nobody there. The second day a child came to look at us. The third day about ten children stood around asking for sous. I was foolish enough to give them some, and the following day there was a crowd of twenty or thirty boys, some of them from sixteen to eighteen years old.

I had the ugly band routed by Claude and the lighthouse keeper and as they took to throwing stones at us I pointed my gun at the little troop. They fled howling. Only two boys, of six and ten years of age, stayed. We did not take any notice of them and I installed myself a little farther on, sheltered by a rock which kept the wind away. The two boys followed. Claude and the lighthouse keeper were on the lookout to see that the boys did not come back. They were stooping down over the extreme point of the rock which was above our heads. They seemed peaceful, when suddenly my young maid jumped up: “Horrors! Madame! Horrors! They are throwing lice down on us!” And, in fact, the two little good-for-nothings had been for the last hour searching for all the vermin they could find on themselves and throwing them on us.

I had the two little beggars seized and they got a well-deserved correction.

There was a crevasse which was called the “Enfer du Plogoff.” I had a wild desire to go down this crevasse, but the guardian dissuaded me, constantly giving as objections the danger of slipping and his fear of responsibility in case of accident. I persisted, nevertheless, in my intention, and after a thousand promises, in addition to a certificate to testify that notwithstanding the supplications of the guardian and the certainty of the danger that I ran, I had persisted all the same, etc., and after having made a small present of ten louis to the brave man, I obtained the facilities for descending the “Enfer du Plogoff”—that is to say a wide belt to which a strong rope was fastened. I buckled this belt round my waist, which was then so slender (forty-three centimeters) that it was necessary to make additional holes in order to fasten it.

Then the guardian put on each of my hands a wooden shoe, the sole of which was bordered with big nails jutting out two centimeters. I stared at these wooden shoes and asked for an explanation before putting them on.

“Well,” said the guardian Lucas, “when I let you down, as you are no fatter than a herringbone, you will get shaken about in the crevasse and will risk breaking your bones; while if you have the sabots on your hands you can protect yourself against the walls by putting out your arms to the right and the left, according as you are shaken up against them. I do not say that you will not have a few—bangs—but that is your own fault, you will go. Now, listen, my little lady: when you are at the bottom, on the rock in the middle, mind you don’t slip, for that is the most dangerous of all; if you fell in the water I might pull the rope, for sure, but I don’t answer for anything. In that cursed whirlpool of water you might be caught between two stones and it would be no use for me to pull—I should break the rope and that would be all.”

Then the man grew pale and making the sign of the cross, he leaned toward me, murmuring in a faint voice: “It is the shipwrecked ones who are there, under the stones, down there. It is they who dance in the moonlight on the shore of the dead (‘Trépassés’). It is they who put the slippery seaweed on the little rock, down there, in order to make travelers slip, and then they drag them to the bottom of the sea.” Then, looking me in the eyes, he said: “Will you go down all the same?”

“Yes, certainly, Père Lucas, I will go down at once.”

My little boy was building forts and castles on the sand with Félicie. Only Claude was with me. He did not say a word, knowing my unbridled desire to meet danger. He looked to see if the belt was properly fastened, and asked my permission to tie the tongue of the belt firmly, then he passed a strong cord several times around to strengthen the leather, and I was let down, suspended by the rope in the blackness of the crevasse. I extended my arms to the right and the left, as the guardian had told me to do, and even then I got my elbows scraped. At first I thought that the noise I heard was the reverberation of the echo of the blows of the wooden shoes against the edges of the crevasse but suddenly a frightful din filled my ears: successive firings of cannon, strident, ringing, crackings of a whip, plaintive howlings and repeated monotonous cries as of a hundred fishermen drawing up a net filled with fish, seaweed, and pebbles. All the noises mingled under the mad violence of the wind. I became furious with myself, for I was really afraid. The lower I went, the louder the howlings became in my ears and my brain; and my heart beat the order of retreat. The wind swept through the narrow tunnel and blew in all directions round my legs, my body, my neck. A horrible fear took possession of me. I descended slowly and at each little shock I felt that the four hands holding me above had come to a knot. I tried to remember the number of knots, for it seemed to me that I was making no progress. Then, filled with terror, I opened my mouth to call out to be drawn up again, but the wind, which danced in mad folly around me, filled my mouth and drove back the words. I was nearly suffocated. Then I shut my eyes and ceased to struggle. I would not even put out my arms. A few moments after I pulled up my legs in unspeakable terror. The sea had just seized them in a brutal embrace which had wet me through. However, I recovered courage, for now I could see clearly. I stretched out my legs and found myself upright on the little rock. It is true it was very slippery. I took hold of a large ring fixed in the vault which overhung the rock and looked round. The long and narrow crevasse grew suddenly larger at its base and terminated in a large grotto which looked out over the open sea; but the entrance of this grotto was protected by a quantity of both large and small rocks which could be seen for a distance of a league in front on the surface of the water—which explains the terrible noise of the sea dashing into the labyrinth and the possibility of standing upright on a rock with the wild dance of the waves all around.

However, I saw very plainly that a false step might be fatal in the brutal whirl of waters which came rushing in from afar with dizzy speed and broke against the insurmountable obstacle, and in receding dashed against other waves which followed them. From this cause proceeded the perpetual fusillade of waters which rushed into the crevasse without danger of drowning me.

The night commenced to fall, and I experienced a fearful anguish in discovering on the crest of a little rock two enormous eyes which looked fixedly at me. Then a little farther, near a tuft of seaweed, two more large, fixed eyes. I saw no body to these beings—nothing but the eyes. I thought for a minute that I was losing my senses, and I bit my tongue till the blood came, then I pulled violently at the rope, as I had agreed to do, in order to give the signal for being drawn up. I felt the trembling joy of the four hands pulling me, and my feet lost their hold as I was lifted up by my guardians. The eyes were lifted up also, troubled to see me go. And while I mounted through the air I saw nothing but eyes everywhere—eyes throwing out long feelers to reach me. I had never seen an octopus, and I did not even know of the existence of these horrible beasts.

During the ascension, which seemed to me interminable, I imagined I saw these beasts along the walls, and my teeth were chattering when I was drawn on to the green hillock.

I immediately told the guardian the cause of my terror, and he crossed himself, saying: “Those were the eyes of the shipwrecked ones. No one must stay there!”

I knew very well that they were not the eyes of shipwrecked ones, but I did not know what they were. For I thought I had seen some strange beasts that no one had ever seen before.

It was only at the hotel, with Père Batifoulé, that I learned to know the octopus.

Only five more days of holiday were left to me, and I passed them at the Pointe du Raz, seated in a niche of rock which has been since named “Sarah Bernhardt’s armchair.” Many tourists have sat there since, and many have sent me verses.

I returned to Paris when my holiday was finished. But I was still very weak and could not take up my work until toward the month of November. I played all the pieces of my répertoire, and I was annoyed at not having any new rôles.

One day Perrin came to see me in my sculptor’s studio. He began to talk at first about my busts; he told me that I ought to do his medallion, and asked me, incidentally, if I knew the rôle of Phèdre. Up to this time I had played only Aricie, and the part of Phèdre seemed formidable to me. I had, however, studied it for my own pleasure.

“Yes, I know the rôle of Phèdre. But I think if ever I had to play it I should die of fright.”

He laughed with his silly little laugh and said to me, squeezing my hand (for he was very gallant): “Work it up; I think that you will play it.”

In fact, eight days after I was called to the directorial office, and Perrin told me that he had announced “Phèdre” for the 21st of December, the fête of Racine, with Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt in the part of Phèdre. I thought I should fall.

“Well, but what about Mlle. Rousseil?” I asked.

“Mlle. Rousseil wishes to have the Committee promise that she shall become an Associate in the month of January, and the Committee, which will without doubt appoint her, refuses to make this promise, and declares that this demand is like a threat. But perhaps Mlle. Rousseil will change her plans, and in that case you will play Aricie and I will change the bill.”

Coming out from Perrin’s I ran up against M. Regnier. I told him of my conversation with the director and of my fears.

“No, no,” said the great artiste to me, “you must not be afraid! I see very well what you are going to make of this rôle. But all you have to do is to be careful and not force your voice. Make the rôle sorrowful rather than furious—it will be better for everyone—even Racine.”

Then, joining my hands, I said: “Dear M. Regnier, help me to work up Phèdre and I shall not be so much afraid.”

He looked at me rather surprised, for in general I was neither docile nor apt to be guided by advice. I own that I was wrong, but I could not help it. But the responsibility which this put upon me made me timid. Regnier accepted and gave me a rendezvous for the following morning at nine o’clock.

Roselia Rousseil persisted in her demand to the Committee, and “Phèdre” was billed for the 21st of December, with Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt for the first time in the rôle of Phèdre.

This caused quite a sensation in the artistic set and in the theater-loving world. That evening over two hundred people were turned away at the ticket office. And when I was told that I began to tremble so much that my teeth chattered.

Regnier comforted me as best he could, saying: “Courage! Cheer up! Are you not the spoiled darling of the public? They will take into consideration your inexperience in important first parts, etc....”

These were the last words he should have said to me. I should have felt stronger if I had known that the public were come to oppose and not to encourage me.

I began to cry bitterly, like a child. Perrin was called and consoled me as well as he could; then he made me laugh by putting powder on my face so awkwardly that I was blinded and suffocated.

Everybody in the theater knew about it and stood at the door of my dressing-room wishing to comfort me. Mounet-Sully, who was playing Hippolyte, told me that he had dreamed: “We were playing ‘Phèdre’ and you were hissed, and my dreams always go by contraries—so,” he cried, “we shall have a tremendous success!”

But what put me completely in a good humor was the arrival of the worthy Martel, who was playing Théramène, and who had come so quickly, believing me ill, that he had not had time to finish his nose. The sight of this gray face with a wide bar of red wax commencing between the two eyebrows, coming down to half a centimeter below his nose and leaving behind it the end of the nose with two large black nostrils—this face was indescribable! And everybody laughed irrepressibly. I knew that Martel made up his nose, for I had already seen this poor nose change shape at the second performance of “Zaïre,” under the tropical depression of the atmosphere; but I had never realized how much he lengthened it. This comical apparition restored all my gayety, and from henceforth I was in full possession of my faculties.

The evening was one long triumph for me. And the Press was unanimous in praise, with the exception of the article of Paul de St. Victor, who was on very good terms with a sister of Rachel, and could not get over my impertinent presumption in daring to measure myself with the great dead artiste; these are his own words, addressed to Girardin, who immediately told me. How mistaken he was, poor St. Victor! I had never seen Rachel act, but I worshiped her talent, for I had surrounded myself with her most devoted admirers, and they little thought of comparing me with their idol.

A few days after this performance of “Phèdre,” the new piece of Bornier was read to us—“La Fille de Roland.” The part of Berthe was confided to me, and we immediately began the rehearsals of this fine piece, whose verses were, nevertheless, a little flat, but which had a real breath of patriotism. There was in this piece a terrible duel, which the public did not see, but which was related by Berthe, the daughter of Roland, while the incidents happened under the eyes of the unhappy girl, who, from a window of the castle followed in anguish the fortunes of the encounter. This scene was the only important one of my much sacrificed rôle.

The piece was ready to be passed when Bornier asked that his friend, Emile Augier, should be present at a general rehearsal. When the play was finished Perrin came to me; he had an affectionate and constrained air. As to Bornier, he came straight to me in a decided and quarrelsome manner. Emile Augier followed him. “Well,” he said to me. I looked straight at him, feeling in this moment that he was my enemy. He stopped short and scratched his head, then turned toward Augier and said:

“I beg you, cher Maître, explain to mademoiselle yourself.”

Emile Augier was a broad man with wide shoulders and a common appearance, at this time rather fat. He was in very good repute at the Théâtre Français, of which he was, for the moment, the successful author. He came near me: “You managed the part at the window very well, mademoiselle, but it is ridiculous; it is not your fault, but that of the author, who has written a most improbable scene. The public would laugh immoderately; this scene must be taken out.”

I turned toward Perrin, who was listening silently: “Are you of the same opinion, sir?”

“I talked it over a short time ago with these gentlemen, but the author is master of his work.”

Then addressing myself to Bornier, I said: “Well, my dear author, what have you decided?”

Little Bornier looked at big Emile Augier. There was in this beseeching and piteous glance an expression of sorrow at having to cut out a scene which he prized, and of fear to vex an Academician just at the time when he was hoping to become a member of the Academy.

“Cut it out! cut it out! or you are done for!” brutally replied Augier, and turned his back. Then poor Bornier, who resembled a Breton gnome, came up to me. He scratched himself desperately, for the unfortunate man had a skin disease which itched terribly. He did not speak. He looked at us questioningly. A poignant anxiety was expressed on his face. Perrin, who had come up to me, guessed the private little drama which was taking place in the heart of the mild Bornier.

“Refuse energetically,” murmured Perrin to me.

I understood, and declared firmly to Bornier that if this scene was taken out I should refuse the part. Then Bornier seized both my hands which he kissed ardently, and running up to Augier he cried with comical emphasis:

“But I cannot take it out! I cannot take it out! She will not play! And the day after to-morrow the play is to be passed!” Then as Emile Augier made a gesture, and would have spoken—“No! No! To put back my play eight days would be to kill it! I cannot take it out! Oh, my God!” And he cried and gesticulated with his two long arms, and stamped with his short legs. His large hairy head went from right to left. He was at the same time funny and pitiful. Emile Augier was irritated, and turned on me like a hunted boar on a pursuing dog:

“You will take the responsibility, mademoiselle, of the absurd window scene at the first presentation?”

“Certainly, monsieur, and I even promise to make of this scene, which I find very fine, an enormous success!”

He rudely shrugged his shoulders, muttering something very disagreeable between his teeth.

When I left the theater I met poor Bornier quite transfigured. He thanked me a thousand times, for he thought very highly of this scene, but dared not thwart Emile Augier. Both Perrin and myself had divined the legitimate emotions of this poor poet, so gentle and so well brought up, but a trifle Jesuitical.

The play was a big success. But the window scene on the night of the first presentation was a veritable triumph.

It was a short time after the terrible war of 1870. The play contained frequent allusions to this, and, owing to the patriotism of the public, had an even greater success than it deserved as a play. I had Emile Augier called. He came into my dressing-room with a surly air and called to me from the door:

“So much the worse for the public! It only proves that the public is an idiot to make a success of such vileness!” And he disappeared without having even entered my dressing-room.

His outburst made me laugh, and as the triumphant Bornier had embraced me repeatedly, I hugged myself in glee.

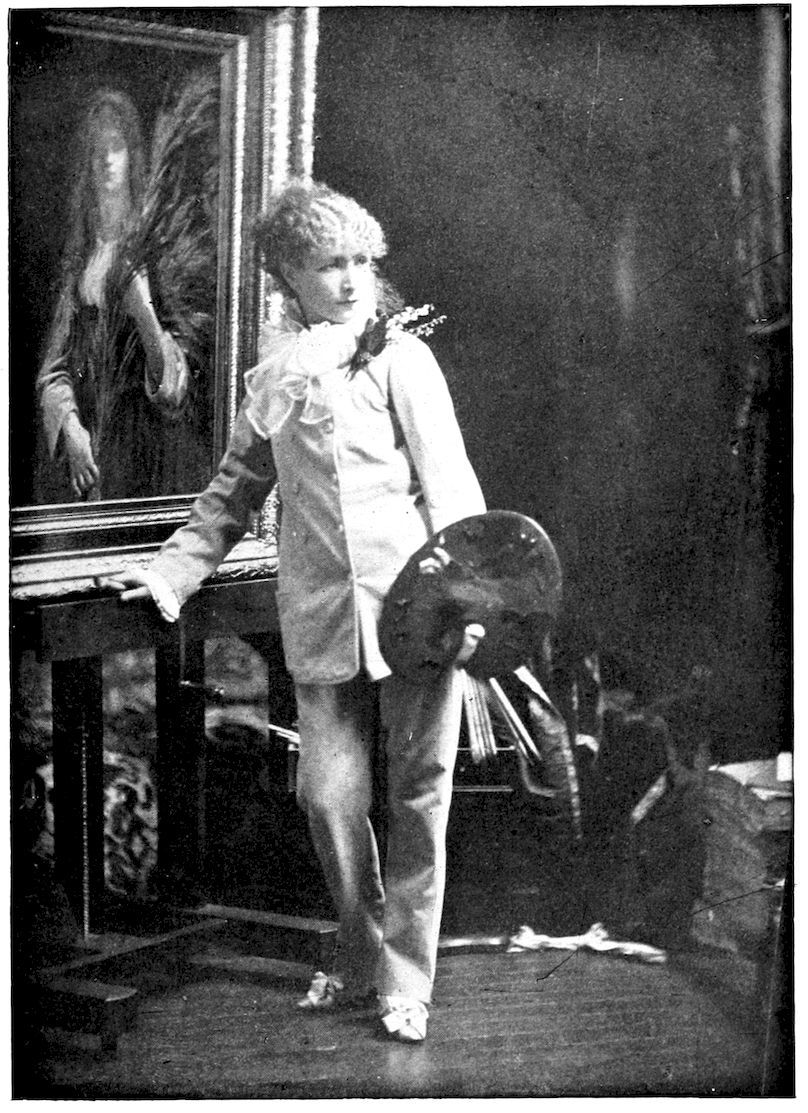

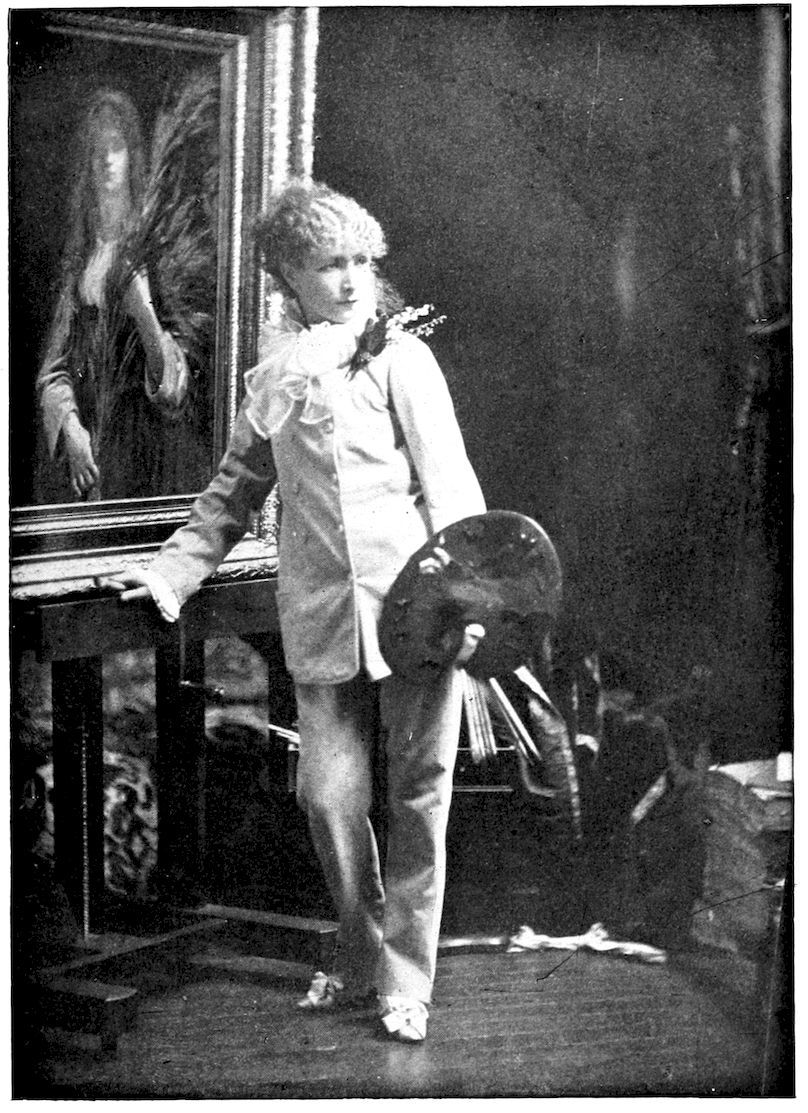

SARAH BERNHARDT PAINTING, 1878–9.

Two months later I played “Gabrielle,” by this same Augier, and I had incessant quarrels with him. I found the verses of this play execrable. Coquelin, who took the part of my husband, had a grand success. As for me, I was as mediocre as the play itself, which is saying much.

I had been admitted Associate in the month of January, and since then it seemed to me that I was in prison, for I had undertaken the engagement not to leave Molière’s Theater for several years. This idea made me sad. It was Perrin who had instigated me to ask to become Associate, and now I regretted it very much.

Almost all the latter part of the year I played only occasionally.

My time was then occupied in looking after the building of a pretty hôtel which I was having constructed at the corner of the Avenue de Villiers and the Rue Fontuny. A sister of my grandmother had left me in her will a nice legacy which I used to buy the ground. My great desire was to have a house that should be entirely my own, and I was then realizing it. The son-in-law of M. Regnier, Félix Escalier, a fashionable architect, was building me a ravishing hôtel! Nothing amused me more than to go with him in the morning over the unfinished house. Then afterwards I mounted the movable scaffolds. Then I went on the roofs. I forgot my worries of the theater in this new occupation. The thing I most desired just now was to become an architect. Then, when the building was finished, the interior had to be thought of. I spent my strength in helping my painter friends who were decorating the ceilings in my bedroom, in my dining-room, in my hall—Georges Clairin, the architect Escalier, who was also a talented painter, Duez, Picard, Butin, Jadin, Jourdain, and Parrot. I was deeply interested, and I recollect a joke which I played on one of my relations. My Aunt Betsy had come from Holland, her native country, to pass a few days in Paris. She was staying with my mother. I invited her to lunch in my new, unfinished habitation. Five of my painter friends were working, some in one room, some in another, and everywhere lofty scaffoldings were erected. In order to be able to climb the ladders more easily I was wearing my sculptor’s costume. My aunt, seeing me thus arrayed, was horribly shocked and told me so. But I was preparing yet another surprise for her. She thought these young workers were ordinary house painters and considered I was too familiar with them. But she nearly fainted when midday came and I rushed to the piano to play “The Complaint of the Hungry Stomachs.” This wild melody had been improvised by the group of painters, but revised and corrected by poet friends. When the song was finished I mounted into my bedroom and made myself into a fine lady for lunch.

My aunt had followed me: “But, my dear,” said she, “you are mad to think I am going to eat with all these workmen. Certainly in all Paris there is no one but yourself who would do such a